A Case Study of Shakespeare's Plays in Gujarati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Wabco India Limited Details of Unclaimed/Unpaid Dividend As on 27-07-2011 Year 2008-09(I)

WABCO INDIA LIMITED DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND AS ON 27-07-2011 YEAR 2008-09(I) Sl. No. Folio no./ Warrant No Name and Address of Shareholder Nature Amount Due date Client id/ of in for Dep id amount (Rs.) transfer to IEPF A/C 1 A00292 3349 A G SATVINDER SING DIVIDEND 205.00 20/01/2016 NO 6 ARULANANDAM MUDALY STREET SANTHOME MADRAS 600004 2 A00328 3951 A KEERTI VARDHANA DIVIDEND 205.00 20/01/2016 15C KUJJU NAICKEN STREET EAST ANNA NAGAR MADRAS 600102 3 EA0659 6248 A MOHAN RAO DIVIDEND 25.00 20/01/2016 20951225 ANDHAVARAPU STREET IN301022 HIRAMANDALAM SRIKAKULAM ANDHRA PRADESH 532459 4 A00345 4181 A RAMACHANDRAN DIVIDEND 103.00 20/01/2016 PROF. OF FORENSIC MEDICINE MEDICAL COLLEGE CALICUT 673008 5 A00278 3132 A S SUBRAMANIAN DIVIDEND 415.00 20/01/2016 27/30 2ND MAIN ROAD INDUSTRIAL TOWN RAJAJINAGAR BANGALORE 560044 6 EA0918 6421 A SRIKANTA MURTHY DIVIDEND 205.00 20/01/2016 30344801 NO 481 IN301926 7TH CROSS 11TH MAIN K C LAYOUT MYSORE 570011 7 EA1012 6982 A VALLIAPPAN DIVIDEND 3.00 20/01/2016 41229303 HONEYWELL TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS P LTD IN302902 151/1 DORAISANIPALYA BANNERGHATA ROAD BANGALORE 560076 8 A00334 4058 A VELU DIVIDEND 63.00 20/01/2016 67A NAGANAKULAM TIRUPPALAI P O MADURAI 625014 WABCO INDIA LIMITED DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND AS ON 27-07-2011 YEAR 2008-09(I) Sl. No. Folio no./ Warrant No Name and Address of Shareholder Nature Amount Due date Client id/ of in for Dep id amount (Rs.) transfer to IEPF A/C 9 A00341 4172 A VIJAYALAKSHMI DIVIDEND 415.00 20/01/2016 56 KUPPANDA GOUNDER STREET POLLACHI 642001 10 -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q3t1s0 Author Balachandran, Jyoti Gulati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Chair This dissertation examines the processes through which a regional community of learned Muslim men – religious scholars, teachers, spiritual masters and others involved in the transmission of religious knowledge – emerged in the central plains of eastern Gujarat in the fifteenth century, a period marked by the formation and expansion of the Gujarat sultanate (c. 1407-1572). Many members of this community shared a history of migration into Gujarat from the southern Arabian Peninsula, north Africa, Iran, Central Asia and the neighboring territories of the Indian subcontinent. I analyze two key aspects related to the making of a community of ii learned Muslim men in the fifteenth century - the production of a variety of texts in Persian and Arabic by learned Muslims and the construction of tomb shrines sponsored by the sultans of Gujarat. -

SAHITYASETU ISSN: 2249-2372 a Peer-Reviewed Literary E-Journal

Included in the UGC Approved List of Journals SAHITYASETU ISSN: 2249-2372 A Peer-Reviewed Literary e-journal Website: http://www.sahityasetu.co.in Year-8, Issue-5, Continuous Issue-47, September-October 2018 Establishment of Good Womanhood: In the Study of Leelavati Jeevankala The research paper attempts to analyze Leelavati’s art of living. Tripathi decided to write this biography to commemorate his elder daughter Leelavati because the book shows Leelavati’s sacrifice, who died of consumption at the age of 21.Moreover the author Vishnu Prasad Trivedi used the epithet “Maharshi” for Tripathi, because he was a philosopher and well informed writer in Gujarati literature. He was well versed in Sanskrit, English and Gujarati languages” (Trivedi 441). He contributed significantly to Gujarati literature. During his lifetime, he wrote poems, novel, drama, biography etc. (Trivedi 48). He has given the great novel Sarasvatichandra, Which runs into 2000 pages and is divided into four parts, which were published in 1887, 1892, 1898 and 1901 respectively. His other notable works include Navalram Nu Kavi Jeevan 1891, Sneh mudra 1898, Madhavram Smarika1900, Leelavati Jeevankala 1905, Dayaram No Akshardeh 1908, Classical Poets of Gujarat 1916. Moreover, he wrote in Samalochak and Sadavastu Vichar. His personal diary Scrap Books also got published after his death (Trivedi 48). He also wrote two Dramas like Sarasvati and Maya and story like Sati chuni. Moreover, He published articles dealing with the subjects pertaining to education and literature (Trivedi Vishnu Prasad 48). His literary repertoire comprises two biographies, Navalramnu Kavijeevan1891 and Leelavati Jeevankala 1905. The biography Navalramnu Kavijeevan focuses on Navalram’s life. -

Download Dialog No-21

EDITOR: Akshaya Kumar EDITORIAL BOARD: Pushpinder Syal Shelley Walia Rana Nayar ADVISORY BOARD: ADVISORY BOARD: (Panjab University) Brian U. Adler C.L. Ahuja Georgia State University, USA lshwar Dutt R. J. Ellis Nirmal Mukerji University of Birmingham, UK N.K.Oberoi Harveen Mann Loyola University, USA Ira Pande Howard Wolf M.L. Raina SUNY, Buffalo, USA Kiran Sahni Mina Singh Subscription Fee: Gyan Verma Rs. 250 per issue or $ 25 per issue Note for Contributors Contributors are requested to follow the latest MLA Handbook. Typescripts should be double-spaced. Two hard copies in MS Word along with a soft copy should be sent to Professor Harpreet Pruthi The Chairperson Department of English and Culture Studies Panjab University Chandigarh160014 INDIA E-mail: [email protected] DIALOG is an interdisciplinary journal which publishes scholary articles, reviews, essays, and polemical interventions. CALL for PAPERS DIALOG provides a forum for interdisciplinary research on diverse aspects of culture, society and literature. For its forthcoming issues it invites scholarly papers, research articles and book reviews. The research papers (about 8000 words) devoted to the following areas would merit our attention most: • Popular Culture Indian Writings in English and Translation • Representations of Gender, Caste and Race • Cinema as Text • Theories of Culture • Emerging Forms ofLiterature Published twice a year, the next two issues of Dialog would carry miscellaneous papers. on the above areas. The contributors are requested to send their papers latest by November, 2012. The papers could be sent electronically at [email protected] or directly to The Editor, Dialog, Department of English and Cultural Studies, Chandigarh -160014. -

Shakespeare in Gujarati: a Translation History

Shakespeare in Gujarati: A Translation History SUNIL SAGAR Abstract Translation history has emerged as one of the most significant enterprises within Translation Studies. Translation history in Gujarati per se is more or less an uncharted terrain. Exploring translation history pertaining to landmark authors such as Shakespeare and translation of his works into Gujarati could open up new vistas of research. It could also throw new light on the cultural and historical context and provide new insights. The paper proposes to investigate different aspects of translation history pertaining to Shakespeare’s plays into Gujarati spanning nearly 150 years. Keywords: Translation History, Methodology, Patronage, Poetics. Introduction As Anthony Pym rightly (1998: 01) said that the history of translation is “an important intercultural activity about which there is still much to learn”. This is why history of translation has emerged as one of the key areas of research all over the world. India has also taken cognizance of this and initiated efforts in this direction. Reputed organizations such as Indian Institute of Advanced Study (IIAS) and Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL) have initiated discussion and discourse on this area with their various initiatives. Translation history has been explored for some time now and it’s not a new area per se. However, there has been a paradigm shift in the way translation history is approached in the recent times. As Georges L. Bastin and Paul F. Bandia (2006: 11) argue in Charting the Future of Translation History: Translation Today, Volume 13, Issue 2 Sunil Sagar While much of the earlier work was descriptive, recounting events and historical facts, there has been a shift in recent years to research based on the interpretation of these events and facts, with the development of a methodology grounded in historiography. -

Objectives the Main Objective of This Course Is to Introduce Students to Archaeology and the Methods Used by Archaeologists

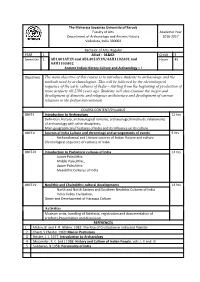

The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Faculty of Arts Academic Year Department of Archaeology and Ancient History 2016-2017 Vadodara, India 390002 Bachelor of Arts: Regular YEAR 1 Allied - 01&02: Credit 3 Semester 1 AB1A01AY1N and AB1A02AY1N/AAH1102A01 and Hours 45 AAH1103A02 Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology – I Objectives The main objective of this course is to introduce students to archaeology and the methods used by archaeologists. This will be followed by the chronological sequence of the early cultures of India – starting from the beginning of production of stone artifacts till 2700 years ago. Students will also examine the origin and development of domestic and religious architecture and development of various religions in the Indian subcontinent COURSE CONTENT/SYLLABUS UNIT-I Introduction to Archaeology 12 hrs Definition, history, archaeological remains, archaeological methods, relationship of archaeology with other disciplines; Main geographical of features of India and its influence on its culture UNIT-II Sources of India Culture and chronology and arrangements of events 5 hrs Archaeological and Literary sources of Indian History and culture Chronological sequence of cultures of India UNIT-III Introduction to Prehistoric cultures of India 14 hrs Lower Paleolithic, Middle Paleolithic, Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic Cultures of India UNIT-IV Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultural developments 14 hrs North and North Eastern and Southern Neolithic Cultures of India Indus Valley Civilization, Origin and Development of Harappa Culture Activities Museum visits, handling of Artefacts, registration and documentation of artefacts,Presentation and discussion REFERENCES 1 Allchin, B. and F. R. Allchin. 1982. The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. -

The Political Historiography of Modern Gujarat

The Political Historiography of Modern Gujarat Tannen Neil Lincoln ISBN 978-81-7791-236-4 © 2016, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. Working Paper Series Editor: Marchang Reimeingam THE POLITICAL HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MODERN -

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century Thesis submitted for the dc^ee fif DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY By AJAZ BANG Under the supervision of PROF. IQTIDAR ALAM KHAN Department of History Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarb- 1983 T388S 3 0 JAH 1392 ?'0A/ CHE':l!r,D-2002 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY TELEPHONE SS46 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that the thesis entitled 'Soci•-Political Condition Ml VB Wtmmimt of Gujarat / during the fifteenth Century' is an original research work carried out by Aijaz Bano under my Supervision, I permit its submission for the award of the Degree of the Doctor of Philosophy.. /-'/'-ji^'-^- (Proi . Jrqiaao;r: Al«fAXamn Khan) tc ?;- . '^^•^\ Contents Chapters Page No. I Introduction 1-13 II The Population of Gujarat Dxiring the Sixteenth Century 14 - 22 III Gujarat's External Trade 1407-1572 23 - 46 IV The Trading Cotnmxinities and their Role in the Sultanate of Gujarat 47 - 75 V The Zamindars in the Sultanate of Gujarat, 1407-1572 76 - 91 VI Composition of the Nobility Under the Sultans of Gujarat 92 - 111 VII Institutional Featvires of the Gujarati Nobility 112 - 134 VIII Conclusion 135 - 140 IX Appendix 141 - 225 X Bibliography 226 - 238 The abljreviations used in the foot notes are f ollov.'ing;- Ain Ain-i-Akbarl JiFiG Arabic History of Gujarat ARIE Annual Reports of Indian Epigraphy SIAPS Epiqraphia Indica •r'g-acic and Persian Supplement EIM Epigraphia Indo i^oslemica FS Futuh-^ffi^Salatin lESHR The Indian Economy and Social History Review JRAS Journal of Asiatic Society ot Bengal MA Mi'rat-i-Ahmadi MS Mirat~i-Sikandari hlRG Merchants and Rulers in Giijarat MF Microfilm. -

The Idea of Gujarat History, Ethnography and Text

The Idea of Gujarat History, Ethnography and Text Edited by EDWARD SIMPSON and MARNA KAPADIA ~ Orient BlackSwan THE IDEA OF GUJARAT. ORIENT BLACKSWAN PRIVATE LIMITED Registered Office 3-6-752 Himayatnagar, Hyderabad 500 029 (A.P), India e-mail: [email protected] Other Offices Bangalore, Bhopal, Bhubaneshwar, Chennai, Ernakulam, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Kolkata, ~ . Luoknow, Mumba~ New Delbi, Patna © Orient Blackswan Private Limited First Published 2010 ISBN 978 81 2504113 9 Typeset by Le Studio Graphique, Gurgaon 122 001 in Dante MT Std 11/13 Maps cartographed by Sangam Books (India) Private Limited, Hyderabad Printed at Aegean Offset, Greater Noida Published by Orient Blackswan Private Limited 1 /24 Asaf Ali Road New Delhi 110 002 e-mail: [email protected] . The external boundary and coastline of India as depicted in the'maps in this book are neither correct nor authentic. CONTENTS List of Maps and Figures vii Acknowledgements IX Notes on the Contributors Xl A Note on the Language and Text xiii Introduction 1 The Parable of the Jakhs EDWARD SIMPSON ~\, , Gujarat in Maps 20 MARNA KAPADIA AND EDWARD SIMPSON L Caste in the Judicial Courts of Gujarat, 180(}-60 32 AMruTA SHODaAN L Alexander Forbes and the Making of a Regional History 50 MARNA KAPADIA 3. Making Sense of the History of Kutch 66 EDWARD SIMPSON 4. The Lives of Bahuchara Mata 84 SAMIRA SHEIKH 5. Reflections on Caste in Gujarat 100 HARALD TAMBs-LYCHE 6. The Politics of Land in Post-colonial Gujarat 120 NIKITA SUD 7. From Gandhi to Modi: Ahmedabad, 1915-2007 136 HOWARD SPODEK vi Contents S. -

The Shaping of Modern Gujarat

A probing took beyond Hindutva to get to the heart of Gujarat THE SHAPING OF MODERN Many aspects of mortem Gujarati society and polity appear pulling. A society which for centuries absorbed diverse people today appears insular and patochiai, and while it is one of the most prosperous slates in India, a fifth of its population lives below the poverty line. J Drawing on academic and scholarly sources, autobiographies, G U ARAT letters, literature and folksongs, Achyut Yagnik and Such Lira Strath attempt to Understand and explain these paradoxes, t hey trace the 2 a 6 :E e o n d i n a U t V a n y history of Gujarat from the time of the Indus Valley civilization, when Gujarati society came to be a synthesis of diverse peoples and cultures, to the state's encounters with the Turks, Marathas and the Portuguese t which sowed the seeds ol communal disharmony. Taking a closer look at the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the authors explore the political tensions, social dynamics and economic forces thal contributed to making the state what it is today, the impact of the British policies; the process of industrialization and urbanization^ and the rise of the middle class; the emergence of the idea of '5wadeshi“; the coming £ G and hr and his attempts to transform society and politics by bringing together diverse Gujarati cultural sources; and the series of communal riots that rocked Gujarat even as the state was consumed by nationalist fervour. With Independence and statehood, the government encouraged a new model of development, which marginalized Dai its, Adivasis and minorities even further. -

OPEN ACCESS RESOURCES on the INTERNET (Book of Papers)

OPEN ACCESS RESOURCES ON THE INTERNET (Book of Papers) Editor Rhoda Bharucha Hon. Director ADINET Seminar organised jointly by Ahmedabad Library Network (ADINET) Information and Library Network Centre (INFLIBNET) Ahmedabad Management Association (AMA) On 26th August, 2006 At Ahmedabad Management Association, Ahmedabad AHMEDABAD LIBRARY NETWORK C/O INFLIBNET Centre, Opp.Gujarat University Guest House, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad-380009 2006 1 © AHMEDABAD LIBRARY NETWORK, AHMEDABAD September, 2006 Ahmedabad Library Network Open access resources on the Internet / Seminar organised jointly by Ahmedabad Library Network (ADINET), Information and Library Network Centre (INFLIBNET) and Ahmedabad Management Association(AMA) on 26rd August 2006. Edited by Rhoda Bharucha - Ahmedabad Library Network, 2006 80p; 24cm.- (Librarians’Day. 2006) “ADINET celebrates the birth anniversary of Dr. S. R. Ranganathan as Librarians’ Day” ISBN : 81-88174-08-04 1 Internet - Resourcess - Access - conference proceedings I Title CC : 24:65(D65)p2,N05 DDC : 028.744 306054 ISBN : 81-88174-08-04 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, without written permission of ADINET. This publication has been sponsored by Director of Libraries, Gujarat State Published by ADINET, Ahmedabad Tele : 079-26305630/26300368/26305971 Fax : 079-26305630/26300990 e-mail : [email protected] Url : www.alibnet.org Cover Design : Divyang Sutaria Printed at Siddhi Offset, Ahmedabad Phone: 25453960 2 CONTENTS Page No. ❖ Preface 4 ❖ About Ahmedabad Library Network (ADINET) 6 ❖ About Information and Library Network Centre (INFLIBNET) 9 1. Key Note Address 11 Shri Manojkumar K. …rhËkðtŒfeÞ rð»tÞðM‚w WŒTƒtuÄ™ 2. Basic Concepts of Open Access and Some Initiatives 16 Dr.