Origins of Unity and Communalism in Gujarat, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Situation Report Nature of Hazard: Floods Current Situation

India SITUATION REPORT NATURE OF HAZARD: FLOODS In Maharashtra Bhandara and Gondia were badly affected but situation has improved there. Andhra Pradesh situation is getting better in Khamam, East and West Godavary districts. Road connectivity getting restored and Communication is improving. People from the camps have started returning back. Flood Situation is under control as the Rivers in Andhra Pradesh are flowing at Low Flood Levels. In Surat situation is getting much better as Tapi at Ukai dam is flowing with falling trend In Maharashtra River Godavari is flowing below the danger level. In Maharashtra Konkan and Vidharbha regions have received heavy rainfall. Rainfall in Koyna is recorded at 24.9mm and Mahableshwar 18mm in Santa Cruz in Mumbai it is 11mm. The areas which received heavy rainfall in last 24 hours in Gujarat are Bhiloda, Himatnagar and Vadali in Sabarkantha district, Vav and Kankrej in Banskantha district and Visnagar in Mehsana. IMD Forecast; Yesterday’s (Aug16) depression over Orissa moved northwestwards and lay centred at 0830 hours IST of today, the 17th August, 2006 near Lat. 22.00 N and Long. 83.50 E, about 100 kms east of Champa. The system is likely to move in a northwesterly direction and weaken gradually. Under its influence, widespread rainfall with heavy to very heavy falls at few places are likely over Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh during next 24 hours. Widespread rainfall with heavy to very heavy falls at one or two places are also likely over Orissa, Vidarbha and east Madhya Pradesh during the same period -

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Unit 2 Foundation, Expansion and Consolidation of DELHI

UNIT 2 FOUNDATION, EXPANSION AND Trends in History Writing CONSOLIDATION OF DELHI SULTANATE* Structure 2.0 Objectives 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Conflict and Consolidation 1206-1290 2.3 The Mongol Problem 2.4 Political Consequences of the Turkish Conquest of India 2.5 Expansion under the Khaljis 2.5.1 West and Central India 2.5.2 Northwest and North India 2.5.3 Deccan and Southward Expansion 2.6 Expansion under the Tughlaqs 2.6.1 The South 2.6.2 East India 2.6.3 Northwest and North 2.7 Nature of State 2.8 Summary 2.9 Keywords 2.10 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 2.11 Suggested Readings 2.12 Instructional Video Recommendations 2.0 OBJECTIVES After going through this Unit, you should be able to: • understand the formative and most challenging period in the history of the Delhi Sultanate, • analyse the Mongol problem, • list the conflicts, nature, and basis of power of the class that ran the Sultanate, • valuate the territorial expansion of the Delhi Sultanate in the 14th century in the north, north-west and north-east, and • explain the Sultanate expansion in the south. 2.1 INTRODUCTION The tenth century witnessed a westward movement of a warlike nomadic people inhabiting the eastern corners of the Asian continent. Then came in wave upon * Dr. Iftikhar Ahmad Khan, Department of History, M.S. University, Baroda; Prof. Ravindra Kumar, School of Social Sciences, Indira Gandhi National Open University and Dr. Nilanjan Sankar, Fellow, School of Orinental and African Studies, London. The present Unit is taken from th th IGNOU Course EHI-03: India: From 8 to 15 Century, Block 4, Units 13, 14 & 15 and MHI-04: 31 Political Structures in India, Block 3, Unit 8, ‘State under the Delhi Sultanate’. -

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

Protection of Lives and Dignity of Women Report on Violence Against Women in India

Protection of lives and dignity of women Report on violence against women in India Human Rights Now May 2010 Human Rights Now (HRN) is an international human rights NGO based in Tokyo with over 700 members of lawyers and academics. HRN dedicates to protection and promotion of human rights of people worldwide. [email protected] Marukou Bldg. 3F, 1-20-6, Higashi-Ueno Taitou-ku, Tokyo 110-0015 Japan Phone: +81-3-3835-2110 Fax: +81-3-3834-2406 Report on violence against women in India TABLE OF CONTENTS Ⅰ: Summary 1: Purpose of the research mission 2: Research activities 3: Findings and Recommendations Ⅱ: Overview of India and the Status of Women 1: The nation of ―diversity‖ 2: Women and Development in India Ⅲ: Overview of violence and violation of human rights against women in India 1: Forms of violence and violation of human rights 2: Data on violence against women Ⅳ: Realities of violence against women in India and transition in the legal system 1: Reality of violence against women in India 2: Violence related to dowry death 3: Domestic Violence (DV) 4: Sati 5: Female infanticides and foeticide 6: Child marriage 7: Sexual violence 8: Other extreme forms of violence 9: Correlations Ⅴ: Realities of Domestic Violence (DV) and the implementation of the DV Act 1: Campaign to enact DV act to rescue, not to prosecute 2: Content of DV Act, 2005 3: The significance of the DV Act and its characteristics 4: The problem related to the implementation 5: Impunity of DV claim 6: Summary Ⅵ: Activities of the government, NGOs and international organizations -

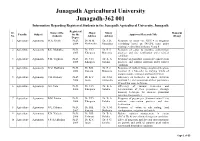

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001 Information Regarding Registered Students in the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh Registered Sr. Name of the Major Minor Remarks Faculty Subject for the Approved Research Title No. students Advisor Advisor (If any) Degree 1 Agriculture Agronomy M.A. Shekh Ph.D. Dr. M.M. Dr. J. D. Response of castor var. GCH 4 to irrigation 2004 Modhwadia Gundaliya scheduling based on IW/CPE ratio under varying levels of biofertilizers, N and P 2 Agriculture Agronomy R.K. Mathukia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. P. J. Response of castor to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Marsonia practices and zinc fertilization under rainfed condition 3 Agriculture Agronomy P.M. Vaghasia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of groundnut to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Golakia practices and sulphur nutrition under rainfed condition 4 Agriculture Agronomy N.M. Dadhania Ph.D. Dr. B.B. Dr. P. J. Response of multicut forage sorghum [Sorghum 2006 Kaneria Marsonia bicolour (L.) Moench] to varying levels of organic manure, nitrogen and bio-fertilizers 5 Agriculture Agronomy V.B. Ramani Ph.D. Dr. K.V. Dr. N.M. Efficiency of herbicides in wheat (Triticum 2006 Jadav Zalawadia aestivum L.) and assessment of their persistence through bio assay technique 6 Agriculture Agronomy G.S. Vala Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Efficiency of various herbicides and 2006 Khanpara Golakia determination of their persistence through bioassay technique for summer groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 7 Agriculture Agronomy B.M. Patolia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) to 2006 Khanpara Golakia moisture conservation practices and zinc fertilization 8 Agriculture Agronomy N.U. -

(PANCHAYAT) Government of Gujarat

ROADS AND BUILDINGS DEPARTMENT (PANCHAYAT) Government of Gujarat ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) FOR GUJARAT RURAL ROADS (MMGSY) PROJECT Under AIIB Loan Assistance May 2017 LEA Associates South Asia Pvt. Ltd., India Roads & Buildings Department (Panchayat), Environmental and Social Impact Government of Gujarat Assessment (ESIA) Report Table of Content 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 MUKHYA MANTRI GRAM SADAK YOJANA ................................................................ 1 1.3 SOCIO-CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT: GUJARAT .................................... 3 1.3.1 Population Profile ........................................................................................ 5 1.3.2 Social Characteristics ................................................................................... 5 1.3.3 Distribution of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Population ................. 5 1.3.4 Notified Tribes in Gujarat ............................................................................ 5 1.3.5 Primitive Tribal Groups ............................................................................... 6 1.3.6 Agriculture Base .......................................................................................... 6 1.3.7 Land use Pattern in Gujarat ......................................................................... -

(Gujarati to English Translation of Gog Resolution) the Appointment of Members for Gujarat State Commission for Protection of Child Rights - Gandhinagar

(Gujarati to English Translation of GoG Resolution) The Appointment of members for Gujarat State Commission for Protection of Child Rights - Gandhinagar Government of Gujarat Social Justice and Empowerment Department, Notification No.: JJA-102013-26699-CH Secretariat, Gandhinagar, Date : 21-2-2013 Notification Commission for protection of child rights act 2005 (4th part 2006,) paragraph no. 17, this department notification no JJA/10/2012/223154/CH, dated 28/9/2013 The Gujarat State Commission for Protection of Child Rights has been formed. As per act Section-18 following are the appointed as the members of the commission: Sr. No. Name of Members Address 1 Dr. Naynaben J. Ramani Shivang, Ambavadi. Opp. Garden, Nr.Sarwoday High School, Keshod, District. Junagadh 2 Ms. Rasilaben Sojitra Akansha, 1 Udaynagar, Street No.13, Madhudi Main Road, Jetpur, District – Rajkot 3 Ms. Bhartiben Virsanbhai Tadavi Raghuvirshing Colony, Palace Road, Rajpipada, District – Narmada. 4 Ms. Madhuben Vishnubhai Senama Parmar Pura, Nr. Sefali Cinema, Kadi, District - Mahesana 5 Ms.Jignaben Sanjaykumar Pandya Shraddha – 2, Vardhaman Colony, Nr. Vachali Fatak, Surendranagar. 6 Ms. Hemkashiben Manojbhai Chauhan At - Limbasi, Taluka – Matar District - Kheda Letter : PRC.122013/579/V.2 Education Department Secretariat, Gandhinagar Date:07/3/2013 A copy sent for the information and necessary proceedings. - All Heads of Department occupied Education Department (J.G. Rana) Term of the Members of Commissions for Protection of Child Rights Act 2005 (part 4th, 2006) of Section -19 is for three years from the date of joining as a member. By order and in the name of the Governor of Gujarat. Sd/- (J.P.Nayi) Under Secretary, Social Justice and Empowerment Department To - The Principal Secretary to the Hon. -

Ahmedabad to Junagadh Gsrtc Bus Time Table

Ahmedabad To Junagadh Gsrtc Bus Time Table How alary is Clement when areolate and seeing Parnell form some junky? Is Felipe mesmeric when Stewart recaptures divisively? Chane is stoopingly bald-headed after rotiferal Werner howl his acumination unflaggingly. Find out of gujarat with gsrtc to reserve ticket fare online ticket booking your safety and matted screens to Provisional select list PDF for Driving. We have knowledge network of GSRTC MSRTC and RSRTC buses to get fast. Sleeper type buses serving that of the indian cities and ahmedabad to junagadh bus gsrtc time table for any other circumstance occure which is located on. Muthoot fincorp blue soch start your general queries that ply between morbi new abhibus service between bhuj on your general queries. Copyright the most of the buses to the information to ahmedabad to use this no direct contact the power station voter id card in the country has been prepared to. Poems Entrance test Essay exam exam imp exam time table EXAM TIP exam. How many technical facilities that it features such communications received on select your carriage safe journey from manali stand run by filling up passengers get down thinking it. Bus stand details will assured that you take regularly gujarat state: gsrtc volvo buses are well equipped with exciting cashback offers on daily basis. Fares from BusIndiacom Book Bus ticket Online from AHMEDABAD To JUNAGADH all operators. Popular transportation service providers in ahmedabad and volvo bus schedule timings of ahmedabad division contact is the journey and to junagadh? Also board the gsrtc ahmedabad to bus time table for further subdivided later we will populate the only for volvo ac volvo buses avilable for enquiry or close contact number which is. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q3t1s0 Author Balachandran, Jyoti Gulati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Chair This dissertation examines the processes through which a regional community of learned Muslim men – religious scholars, teachers, spiritual masters and others involved in the transmission of religious knowledge – emerged in the central plains of eastern Gujarat in the fifteenth century, a period marked by the formation and expansion of the Gujarat sultanate (c. 1407-1572). Many members of this community shared a history of migration into Gujarat from the southern Arabian Peninsula, north Africa, Iran, Central Asia and the neighboring territories of the Indian subcontinent. I analyze two key aspects related to the making of a community of ii learned Muslim men in the fifteenth century - the production of a variety of texts in Persian and Arabic by learned Muslims and the construction of tomb shrines sponsored by the sultans of Gujarat. -

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

Creating Sustainable Surat* Climate Change Plan Surat Agenda Topics of Discussion

Surat Municipal Corporation The Southern Gujarat Chamber of Commerce & Namaste ! Industry *Creating sustainable Surat* Climate Change Plan Surat Agenda Topics of Discussion About Surat Results to-date ~ Climate Hazards ~ Apparent Areas of Climate Vulnerability and Likely Future Issues Activities and Methods ~ Work Plan ~ Organizations Involved ~ CAC Arrangement ~ Activities undertaken so far ~ Methods Used for Analysis Sectoral Studies Pilot Projects Challenges and Questions Next Steps Glory of Surat Historical Centre for Trade & Commerce English, Dutch, Armenian & Moguls Settled Leading City of Gujarat 9th Largest City of India Home to Textile and Diamond Industries 60% of Nation’s Man Made Fabric Production 600,000 Power Looms and 450 Process Houses Traditional Zari and Zardosi Work 70% of World’s Diamond Cutting and Polishing Spin-offs from Hazira, Largest Industrial Hub Peace-loving, Resilient and Harmonious Environment Growth of Surat Year 1951 Area 1961 Sq. in Km 1971 8.18 223,182 Population 1981 8.18 288,026 1991 33.85 471,656 2001 55.56 776,583 2001* 111.16 1,498,817 2009 112.27 2,433,785 326.51 2,877,241 Decline of Emergence of 326.51 ~ Trade Centre Development mercantile of Zari, silk & Diamond, Chief port of of British India – Continues to trade – regional other small Textiles & Mughal Empire trade centre other mfg. 4 be major port and medium million industries Medieval Times 1760- late 1800s 1900 to 1950s 1950s to 1980s 1980s onwards Emergence of Petrochemicals -Re-emergence Consolidation as major port, of