Download Dialog No-21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. NEW ADDITION to PARLIAMENT LIBRARY English Books

December 2010 I. NEW ADDITION TO PARLIAMENT LIBRARY English Books 000 GENERALITIES 1 Ripley's believe it or not: seeing is believing / [text by Geoff Tibball].-- Florida: Ripley Publishing, 2009. 254p.: plates: illus.; 30cm. ISBN : 978-1-893951-45-7. R 031.02 RIP B193032 2 Sparks, Karen Jacobs, ed. Encyclopaedia Britannica book of the year 2010: book of the year / edited by Karen Jacobs Sparks.-- New Delhi: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2010. 880p.: plates: tables: illus.; 29cm. ISBN : 978-1-61535-331-6. R 032 SPA-en B193014 3 Porterfield, Christopher, ed. 85 years of great writing in Time: 1923-2008 / edited by Christopher Porterfield.-- New York: Time Books, 2008. 560p.: illus.; 24cm. ISBN : 1-60320-018-5. 070.44 POR-eig B193000 4 Esipisu, Manoah Eyes of democracy: the media and elections / Manoah Esipisu and Isaac E. Khaguli.-- London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 2010. xiii, 124p.; 26cm. ISBN : 978-0-85092-898-3. 070.44932091724 ESI-ey B193118 5 Khan, Mohammad Ayub Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan: a selection of talks and interviews 1964-1967 / Mohammad Ayub Khan; transcribed and edited by Nadia Ghani;.-- Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. xvii, 315p.: plates; 24cm. ISBN : 978-0-19-547624-8. 080 KHA-f B192808 6 Singh, S. Nihal People and places / S. Nihal Singh.-- Gurgaon: Shubhi Publications, 2009. viii, 219p.; 22cm. ISBN : 81-829019-8-7. 080 SIN-p B193119 7 Bansali, Jyoti, ed. Exploring mind pollution / edited by Jyoti Bhansali and Sushma Singhvi.-- New Delhi: Gunjan Foundation, 2010. vi, 166p.; 22cm. ISBN : 978-81-910088-0-7. 128.2 Q0 B193427 100 PHILOSOPHY AND PSYCHOLOGY 8 Wimer, Howard Inner guidance and the four spiritual gifts: how to maximize your intuition and inspirations to become more creative, successful and fulfilled / Howard Wimer.— New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2010. -

A Tea Party Ruth Prawer Jhabvala Ruth Prawer Jh

Unit – I: Wit and Humour & Sir Mokshagundam Vishveshvaraya Wit and Humour: A Tea Party - Ruth Prawer Jhabvala Ruth Prawer Jhabvala was born in Cologne, Germany, into a patriotic Jewish family. They escaped to Britain in April 1939. In 1951, she married Cyrus Jhabvala , a Parsee architect whom she had met in London, and went to live with him in Delhi. She plunged in 'total immersion' into India – the jasmine, the starlit nights, the temple bells, the holy men, the heat. She bore three daughters, wore the sari and wrote of India and the Indians as if she were Indian herself. But her passionate love for India changed into its opposite. By 1975, she found she could no longer write of it nor in it. Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, died at the age of 85, achieved her greatest fame as a writer late in life, and for work she had once dismissed as a hobby – she had considered “writing film scripts” just as a recreation. Her original screenplays and adaptations of literary classics for the film producer Ismail Merchant and the director James Ivory were met with box-office and critical success. The trio met in 1961, and almost immediately became collaborators, as well as close and lifelong friends. Her dozen novels and eight collections of short stories (and other stories published in the New Yorker and elsewhere) won Jhabvala the admiration of the sternest critics of her time. Raymond Mortimer thought she beat all other western novelists in her understanding of modern India. To CP Snow, no other living writer better afforded readers that “definition of the highest art”, the feeling “that life is this and not otherwise”. -

SAHITYASETU ISSN: 2249-2372 a Peer-Reviewed Literary E-Journal

Included in the UGC Approved List of Journals SAHITYASETU ISSN: 2249-2372 A Peer-Reviewed Literary e-journal Website: http://www.sahityasetu.co.in Year-8, Issue-5, Continuous Issue-47, September-October 2018 Establishment of Good Womanhood: In the Study of Leelavati Jeevankala The research paper attempts to analyze Leelavati’s art of living. Tripathi decided to write this biography to commemorate his elder daughter Leelavati because the book shows Leelavati’s sacrifice, who died of consumption at the age of 21.Moreover the author Vishnu Prasad Trivedi used the epithet “Maharshi” for Tripathi, because he was a philosopher and well informed writer in Gujarati literature. He was well versed in Sanskrit, English and Gujarati languages” (Trivedi 441). He contributed significantly to Gujarati literature. During his lifetime, he wrote poems, novel, drama, biography etc. (Trivedi 48). He has given the great novel Sarasvatichandra, Which runs into 2000 pages and is divided into four parts, which were published in 1887, 1892, 1898 and 1901 respectively. His other notable works include Navalram Nu Kavi Jeevan 1891, Sneh mudra 1898, Madhavram Smarika1900, Leelavati Jeevankala 1905, Dayaram No Akshardeh 1908, Classical Poets of Gujarat 1916. Moreover, he wrote in Samalochak and Sadavastu Vichar. His personal diary Scrap Books also got published after his death (Trivedi 48). He also wrote two Dramas like Sarasvati and Maya and story like Sati chuni. Moreover, He published articles dealing with the subjects pertaining to education and literature (Trivedi Vishnu Prasad 48). His literary repertoire comprises two biographies, Navalramnu Kavijeevan1891 and Leelavati Jeevankala 1905. The biography Navalramnu Kavijeevan focuses on Navalram’s life. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 11: 7 July 2011

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 11 : 7 July 2011 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. Aspects of Autobiography and Biography in Indian Writing in English Editors Pauline Das, Ph.D. K. R. Vijaya, Ph.D. Amutha Charu Sheela, M.A., M.Phil., M.B.A. Contents 1. Introduction/Preface … Pauline Das, Ph.D., K. R. Vijaya, Ph.D. and Amutha Charu Sheela, M.A., M.Phil., M.B.A. 2. Memoirs of a Patchwork Life … Maneeta Kahlon, Ph.D. 3. A Kaleidoscopic View of Kamala Das’ My Story … R. Tamil Selvi, M.A., M.Phil. 4. Abdul Kalam: A Complete Man … Somasundari Latha, M.A., M.Ed., M.Phil. 5. Recollections of the Development of My Mind and Character: the Autobiography of Charles Darwin … Pauline Das, Ph.D. Language in India www.languageinindia.com 11 : 7 July 2011 Issue pages for this Book 771-826 Pauline Das, Ph.D., K. R. Vijaya, Ph.D., and Amutha Charu Sheela, M.A., M.Phil., M.B.A. Aspects of Autobiography and Biography in Indian Writing in English 1 6. Gandhi’s Autobiography as a Discourse on His Spiritual Journey … K. R. Vijaya, Ph.D. 7. Autobiography as a Tool of Nationalism … B. Subhashini Meikandadevan, M.A., M.Phil. and P. -

The Shaping of Modern Gujarat

A probing took beyond Hindutva to get to the heart of Gujarat THE SHAPING OF MODERN Many aspects of mortem Gujarati society and polity appear pulling. A society which for centuries absorbed diverse people today appears insular and patochiai, and while it is one of the most prosperous slates in India, a fifth of its population lives below the poverty line. J Drawing on academic and scholarly sources, autobiographies, G U ARAT letters, literature and folksongs, Achyut Yagnik and Such Lira Strath attempt to Understand and explain these paradoxes, t hey trace the 2 a 6 :E e o n d i n a U t V a n y history of Gujarat from the time of the Indus Valley civilization, when Gujarati society came to be a synthesis of diverse peoples and cultures, to the state's encounters with the Turks, Marathas and the Portuguese t which sowed the seeds ol communal disharmony. Taking a closer look at the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the authors explore the political tensions, social dynamics and economic forces thal contributed to making the state what it is today, the impact of the British policies; the process of industrialization and urbanization^ and the rise of the middle class; the emergence of the idea of '5wadeshi“; the coming £ G and hr and his attempts to transform society and politics by bringing together diverse Gujarati cultural sources; and the series of communal riots that rocked Gujarat even as the state was consumed by nationalist fervour. With Independence and statehood, the government encouraged a new model of development, which marginalized Dai its, Adivasis and minorities even further. -

BLOGS Dow Shalt Pay for Bhopal Just for the Record, and Those

BLOGS Dow Shalt Pay For Bhopal Just for the record, and those who missed it earlier, thanks to a revival on Twitter -- and perhaps because of that the resulting emails today -- of the old Yes Men hoax/prank on BBC. The Yes Men explain the background: Dow claims the company inherited no liabilities for the Bhopal disaster, but the victims aren't buying it, and have continued to fight Dow just as hard as they fought Union Carbide. That's a heavy cross to bear for a multinational company; perhaps it's no wonder Dow can't quite face the truth. The Yes Men decided, in November 2002, to help them do so by explaining exactly why Dow can't do anything for the Bhopalis: they aren't shareholders. Dow responded in a masterfully clumsy way, resulting in a flurry of press. Two years later, in late November 2004, an invitation arrived at the 2002 website, neglected since. On the 20th anniversary of the Bhopal disaster, "Dow representative" "Jude Finisterra" went on BBC World TV to announce that the company was finally going to compensate the victims and clean up the mess in Bhopal. The story shot around the world, much to the chagrin of Dow, who briefly disavowed any responsibility as per policy. The Yes Men again helped Dow be clearer about their feelings. (See also this account, complete with a story of censorship.) Only months after Andy's face had been on most UK tellies, he appeared at a London banking conference as Dow rep "Erastus Hamm," this time to explain how Dow considers death acceptable so long as profits still roll in. -

An Interview with Author Jerry Pinto Edited by Maya Vinai1

‘We live and love on a fissure’: An Interview with author Jerry Pinto Edited by Maya Vinai1 Photo: Vedika Singhania Jerry Pinto is one of India’s most prominent names in literature; equally appropriated and applauded by staunch critics and connoisseurs. Apart from being an author, he has worked as a journalist and as a faculty member in his native city of Mumbai. Apart from his fiction, non- fiction, poems and memoir, he has written books for children and has put together some very well-received anthologies. Jerry Pinto’s works have won him a plethora of accolades. His first novel, Em and the Big Hoom (2012) was awarded India’s highest honour from the Academy of Letters, the Sahitya Akademi, for a novel in English; the Windham-Campbell Prize supervised by the Beinecke Library, Yale, USA; the Hindu ‘Lit for Life’ Award, and the Crossword Award for fiction. Helen: the Life and Times of a Bollywood H-Bomb (2006) won the National Award for the Best Book on Cinema. His translations from Marathi of Mallika Amar Sheikh’s autobiography I Want to Destroy Myself was shortlisted for the Crossword Award for Fiction. Furthermore, his graphic novel in collaboration with Garima Gupta was shortlisted for the Crossword Award for Children’s Fiction. His translation of the Dalit writer Baburao Bagul’s When I Hid My Caste won the Fiction Prize at the Bangalore Literary Festival in 2018 and his novel Murder in Mahim (2017) won the Valley of Words Prize, and was shortlisted for the Crossword Award for Fiction and the Mumbai Academy of the Moving Image Prize. -

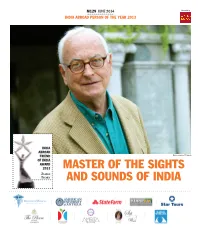

Master of the Sights and Sounds of India

M129 JUNE 2014 Presented by INDIA ABROAD PERSON OF THE YEAR 2013 INDIA ABROAD FRIEND FRANCO ORIGLIA/GETTY IMAGES OF INDIA AWARD 2013 MASTER OF THE SIGHTS JAMES IVORY AND SOUNDS OF INDIA M130 JUNE 2014 Presented by INDIA ABROAD PERSON OF THE YEAR 2013 ‘I still dream about India’ Director James Ivory , winner of the India Abroad Friend of India Award 2013 , speaks to Aseem Chhabra in his most eloquent interview yet about his elegant and memorable films set India Director James Ivory, left, and the late producer Ismail Merchant arrive at the Deauville American Film Festival in France, where Ivory was honored, in 2003. Their partnership lasted over four decades, till Merchant’s death in May 2005. James Ivory For elegantly creating a classic genre; for a repertoire of exquisitely crafted films; for taking India to the world through cinema. PHILIPPE WOJAZER/REUTERS ames Ivory’s association with India goes back nearly remember it very clearly. When we made Shakespeare Wallah it six decades when he first made two documentaries We made four feature films in a row and I think of that was much better. Plus we couldn’t see our about India. He later directed six features in India — time as a heroic period in the history of MIP ( Merchant rushes. We weren’t near any place where Jeach an iconic representation of India of that time Ivory Productions ). We had no money and it was very hard we could project rushes with sound. For period. to raise money to make the kind of films we wanted to The Householder we found a movie theater Ivory, 86, recently sat in the sprawling garden of his coun - make. -

Annual Report 2009-2010

Annual Report NDIA NTERNATIONAL ENTRE I I I C -2010 ND 2009 I A I NTERNAT I ONAL C ENTRE Annual Report Annual 2009 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE -2010 40 Max Mueller Marg New Delhi 110 003 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE New Delhi Annual Report INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE 2009-2010 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE New Delhi Board of Trustees Professor M.G.K. Menon, President Justice B. N. Srikrishna Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan Mr. L. K. Joshi Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee Professor S.K. Thorat Mr. N. N. Vohra Dr. Kavita A. Sharma Executive Members Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Prof. Rajasekharan Pillai Mr. Kisan Mehta Dr. K.T. Ravindran Mr. Keshav N. Desiraju Mr. M.P. Wadhawan, Hon. Treasurer Lt. Gen. V.R. Raghavan Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Mr. Vipin Malik Finance Committee Dr. Shankar N. Acharya, Chairman Mr. M.P. Wadhawan, Hon. Treasurer Mr. Pradeep Dinodia, Member Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Chief Finance Officer Lt. Gen. (Retd.) V.R. Raghavan, Member Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Medical Consultants Dr. K.P. Mathur Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. B. Chakravorty Dr. Mohammad Qasim IIC Senior Staff Ms. Premola Ghose, Chief Programme Division Mr. A.L. Rawal, Dy. General Manager (C) Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief Maintenance Division Mrs. Shamole Aggarwal, Dy. General Manager (H) Mrs. Ira Pande, Chief Editor Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance and Accounts Officer Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Mrs. Sushma Zutshi, Librarian Mr. Vijay Kumar Thukral, Executive Chef Mr. K.S. Kutty, Membership Officer -2010 Annual Report 2009 It is my privilege to present the forty-ninth Annual Report of the India International Centre for the year commencing 1 February, 2009 and ending on 31 January, 2010. -

Dom Moraes: My Son's Father and Never at Home

Chapter Four Dom Moraes: My Son's Father and Never At Home • Chapter IV Dom Moraes: My Son's Father and Never At Home Dom Moraes was a man of chequered career, a poet, journalist, biographer, autobiographer, translator, and writer of travelogues. He is one of the significant Indian English writers of the first generation of post- independent India. Dom was born in a wealthy Goan Catholic Christian family in 1938, with a high educational background. He was the only son of Dr. Beryl and Frank Moraes. His father was a London returned barrister, a student of Oxford and the first non-British editor of the Times of India; and his mother was a pathologist. As a child of seven years, he suffered from the trauma of his mother's nervous breakdown and eventual descent into clinical insanity. He accompanied his father on his travels through South-East Asia, the Pacific, Australia, New Zealand and Sri Lanka, the places he had to visit once again as a journalist. At the age of 16 he went to London and lived there for more than 20 years. From his adolescence Dom made himself controversial by trying to assert his identity as an Englishman. He even became an English Citizen in 1961. In 1956, aged 18, he was courted by Henrietta Moraes. They married in 1961. He left her, but did not divorce her. He married Judith and had a son, Heff Moraes. However, this marriage could not last long. He later married celebrated Indian actress and beauty Leela Naidu and they were a star couple, known across several continents, for over two decades. -

Artist Index

Artist Index A Asha Parekh (1950s, 1960s, 1970s) Bharati (1960s) A.K. Hangal (1970s, 1980s) Asha Potdar (1970s) Bharti (1970s) Aamir Khan (1970s, 1980s) Asha Sachdev (1970s) Bhola (1970s) Aarti (1970s) Ashish Vidyarthi (1990s) Bhudo Advani (1950s, 1960s, 1970s) Abhi Bhattacharya (1950s, 1960s, Ashok Kumar (1930s, 1940s, 1950s, Bhupinder Singh (1960s) 1970s) 1960s, 1970s) Bhushan Tiwari (1970s) Achala Sachdev (1950s, 1960s, Ashoo (1970s, 1980s) Bibbo (1940s) 1970s) Asit Sen (1950s, 1960s, 1970s) Bihari (1970s) Aditya Pancholi (1980s) Aspi Irani- director (1950s) Bikram Kapoor (1960s) Agha (1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s) Asrani (1970s) Bina Rai (1950s, 1960s) Ahmed- dancer (1950s) Avtar Gill (1990s) Bindu (1960s, 1970s) Ajay Devgan (1990s) Azad (1960s) Bipin Gupta (1940s, 1960s, 1970s) Ajit (1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s) Azim (1950s, 1960s) Bir Sakhuja (1950s, 1960s) Alan Figueiredo- musician, dancer Azra (1960s, 1970s) Birbal (1970s) (1960s) Bismillah (1930s) Alankar (Master) (1970s) B Bittoo (Master) (1970s) Alka (1970s) B.M. Vyas (1960s) Biswajeet (1960s) Amar (1940s, 1960s) B. Nandrekar (1930s) Bob Christo (1980s, 1990s) Amarnath (1950s, 1960s) Babita (1960s, 1970s) Brahm Bhardwaj (1960s, 1970s) Ameerbai Karnataki (1940s, 1960s) Baburao Pendharkar (1930s, 1940s) Ameeta (1950s, 1960s) Baby Farida (see Farida) C Amitabh Bachchan (1970s, 1980s, Baby Leela (see Leela) C.S. Dubey (1970s, 1980s) 1990s) Baby Madhuri (see Madhuri) Chaman Puri (1970s) Amjad Khan (1950s, 1980s) Baby Naaz (see Kumari Naaz) Chandramohan (1930s, 1940s) Amol Palekar (1970s)