Identity and Difference in a Muslim Community in Central Gujarat, India Following the 2002 Communal Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Estimated Population by Castes Kutch

• 1, .. ESTIMATED POPULATION BY CASTES" -1951 .iI> . '. 14. I " Office of the Registrar General, India MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS _- GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 1954 //' / .. 315.475 # 1951 OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL. INDIA. NEW DELHI. • 2011 (LIBRARY) lass No._ 315.475 ,ookNo. _ 1951 Est P ~ccession No 21115 CONTENTS ,PAGES t. INTRODUCTION • • I 2' Table I.-Population.iof Scheduled Castes . 2-3 3· Table H.-Population of Scheduled Tribes . 4-5 4- Table HI.-Population of Backward Classes • • I I (i) Hindus . • • • 6-n (ii) Muslims J 5· Table IV.-Population of Other Castes • • , (i) Hindus. 12-I S .... \ ~ I (ii) Muslims • • J In pursuance of Government policy there was limited enumeration and tabulation of castes in 1951 Census. Even in the Case of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Backward Classes, the figures of each caste were not separately extracted; only the group totals wore ascertained. The Backward Classes Commission require the figures of population of each caste. In order to Dssist them an estimate of population of each caste in 1951 has been made on the basis of the figures of the previous censuses. 2. The figures have been presented in four tables:- (i) Scheduled Castes, Hindus only (1i) Scheduled. Tribes (iii) Backward Classes Hindus and Muslims separately (Iv) Other Castes, Hindus and Muslims se.parately. Some 'minor adjustments have been matle in the estimated figures of Scheduled Tri bes in order to make the total tally with the 1951 - Census total of this group. 3. ho castew1se figures are available for lF41 Census. The tables of 1941 Census give figures for only a few selected castes and these also for a few selected distric ts. -

Kheda District Disaster Management Plan

KHEDA DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN Name of the District Kheda Previous plan submitted month & year june 2017 Plan updated month & year may 2017 Signature of District Collector Emergency operation center Collector office – Kheda (Nadiad) & Gujarat state Disaster Management Authority Message Gujarat State has faced a cocktail of disasters such as Flood of 1978, Cyclone of 1998, Earthquake of 2001 and Flood of 2005-06. Government of Gujarat has set up a nodal agency Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority to manage disasters in the State. Kheda District is vulnerable to natural disasters like earthquake, flood, cyclone and man- made disasters like road & rail accidents, fire, epidemics, riots. Many a time it is not possible to prevent disasters but awareness & sensitization of people regarding preparedness and mitigation of various disasters gives positive results. Collectorate-Kheda have tried to include the district related information, risks and preparedness against risks, responses at the time of disasters as well as disaster management and strategy during the disaster etc. for Kheda District. This is updated periodically and also we are improving it through our draw, errors and learn new lessons. District Disaster Management Plan (DDMP) is in two parts. Part-1 includes District profile of various disasters, action plans including IRS (Incident Response System). And Part-2 includes detalied version of DDMP as per the guidelines provided by GSDMA. Kheda - Nadiad Dr. Kuldeep Arya I.A.S June - 2017 Collector CHACKLIST Given below is the general list of important actions / items required in a Disaster. Please check out the items pertaining to your area / function. District Collector is the chief custodian of this plan document and also ensures that this plan document is reviewed and update regularly. -

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

JUNAGADH (GUJARAT) Details of Students Admitted in Under Graduate Course for the Year 2019 - 2020

NOBLE AYURVED COLLEGE & RESEARCH INSTITUTE - JUNAGADH (GUJARAT) Details of Students Admitted in Under Graduate Course for the Year 2019 - 2020 Category Fee Receipt Number and NEET Sr. No. Name of Student Father's Name Date of Birth Residential Address Govt./Management Quota % of PCB in + 10+2 (Gen./SC/ST/OBC/ Date Score Other) 113-A, Ramnagar Society, Anjar, Ta.- 1 Soni Ankit Mahendrabhai 05/10/2001 User Id 15730 & 23/10/2019 Government 87.78% 343 GENERAL Anjar, Dist.-Kachchh, Gujarat-370110 Block No.-53/21, Street No.-4, Mayur Town Ship, Opp. Maru Kansara Hall, 2 Ajudiya Sonalben Mukeshbhai 12/09/2001 User Id 02349 & 23/10/2019 Government 64.22% 326 GENERAL Ranjit Sagar Road, Jamnagar - 361005, Gujarat 390, Panchayat Street, Bhadrod, 3 Kalsariya Vaishaliben Ranabhai 10/09/2000 User Id 10407 & 23/10/2019 Government 84.44% 320 SEBC Bhavnagar, Gujarat-364295 "NISARG", Gayatri Society, Near Hanuman 4 Humbal Anjaliben Karashanbhai 31/07/2002 User Id 28410 & 23/10/2019 Government 73.78% 319 SEBC Tempal, Manavadar-362630, Gujarat K-22, Dharti Society, Mahudha Road, 5 Vaghela Nidhi Jagdishkumar 02/10/2000 User Id 17136 & 23/10/2019 Mahemdavad-387130, Dist.- Kheda, Government 57.11% 314 GENERAL Gujarat Near Swaminarayan Mandir, 6 Vanani Ansi Rajubhai 01/08/2002 User Id 64826 & 23/10/2019 Surka, Ugamedi, Gadhada, Bhavnagar - Government 65.33% 313 GENERAL 364765, Gujarat Mota Vadala (Sindhudi), Taluka - Kalavad, 7 Busa Anand Jamanbhai 02/01/2002 User Id 24445 & 23/10/2019 District - Jamnagar, Pincode - 361162, Government 66.67% 312 GENERAL Gujarat Plot No. 717 A/2, RTO Road, Nandigram School Pachhal, 8 Patel Diyaben Sanjaykumar 17/02/2002 User Id 12963 & 23/10/2019 Government 57.78% 311 GENERAL Bhavnagar, Vijayrajnagar, Bhavnagar - 364001, Gujarat 11, Tribhovan Park Society, Nandigram 9 Parmar Sanket Dilipbhai 02/09/2001 User Id 04499 & 23/10/2019 Road, Government 67.11% 302 SEBC Station Road, Limbdi - 363421, Gujarat "GOKULESH", G.E.B. -

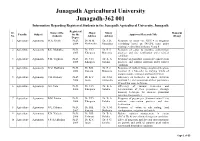

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001 Information Regarding Registered Students in the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh Registered Sr. Name of the Major Minor Remarks Faculty Subject for the Approved Research Title No. students Advisor Advisor (If any) Degree 1 Agriculture Agronomy M.A. Shekh Ph.D. Dr. M.M. Dr. J. D. Response of castor var. GCH 4 to irrigation 2004 Modhwadia Gundaliya scheduling based on IW/CPE ratio under varying levels of biofertilizers, N and P 2 Agriculture Agronomy R.K. Mathukia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. P. J. Response of castor to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Marsonia practices and zinc fertilization under rainfed condition 3 Agriculture Agronomy P.M. Vaghasia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of groundnut to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Golakia practices and sulphur nutrition under rainfed condition 4 Agriculture Agronomy N.M. Dadhania Ph.D. Dr. B.B. Dr. P. J. Response of multicut forage sorghum [Sorghum 2006 Kaneria Marsonia bicolour (L.) Moench] to varying levels of organic manure, nitrogen and bio-fertilizers 5 Agriculture Agronomy V.B. Ramani Ph.D. Dr. K.V. Dr. N.M. Efficiency of herbicides in wheat (Triticum 2006 Jadav Zalawadia aestivum L.) and assessment of their persistence through bio assay technique 6 Agriculture Agronomy G.S. Vala Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Efficiency of various herbicides and 2006 Khanpara Golakia determination of their persistence through bioassay technique for summer groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 7 Agriculture Agronomy B.M. Patolia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) to 2006 Khanpara Golakia moisture conservation practices and zinc fertilization 8 Agriculture Agronomy N.U. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q3t1s0 Author Balachandran, Jyoti Gulati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Chair This dissertation examines the processes through which a regional community of learned Muslim men – religious scholars, teachers, spiritual masters and others involved in the transmission of religious knowledge – emerged in the central plains of eastern Gujarat in the fifteenth century, a period marked by the formation and expansion of the Gujarat sultanate (c. 1407-1572). Many members of this community shared a history of migration into Gujarat from the southern Arabian Peninsula, north Africa, Iran, Central Asia and the neighboring territories of the Indian subcontinent. I analyze two key aspects related to the making of a community of ii learned Muslim men in the fifteenth century - the production of a variety of texts in Persian and Arabic by learned Muslims and the construction of tomb shrines sponsored by the sultans of Gujarat. -

Islam in Kenya: the Khoja Ismilis

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT VJORLD AFFAIRS DER- 31 & 32 November 26, 1954 Islam in Kenya c/o Barclays Bank Introduction Queeusway Nairobi, Kenya Mr. Walter S. Rogers (Delayed fr revl sl Institute of Current World Affairs 522 Fifth Avenue New York 36, New York Dear Mr. Roers: All over the continent of Africa, from Morocco and Egypt to Zanzibar, Cape Town and Nigeria, millions of eople respond each day to a ringing cry heard across half the world for 1300 years. La i.l.aha illa-'llah: Muhmmadun rasulm,'llh, There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his Prophet By these words, Muslims declare their faith in the teachings of the Arabian Prophet. The religion was born in Arabia and the words of its declaration of faith are in Arabic, but Islam has been accepted by many peoples of various races, natioual- i tie s and religious back- grounds, includiu a diverse number iu Kenya. Iu this colony there are African, Indian, Arab, Somali, Comoriau and other Muslims---even a few Euglishmeu---aud they meet each Frlday for formal worship in mosques iu Nairobi, Mombasa, Lamu and Kisumu, in the African Resewves and across the arid wastes of the northern frontier desert. Considerable attention has been given to the role of Christianity in Kenya and elsewhere iu East Africa, Jamia (Sunni) Mosque, and rightly so. But it Nairobl is sometimes overlooked that another great mouo- theistic religiou is at work as well. Islam arose later iu history than Christianity, but it was firmly planted lu Kenya centuries before the first Christian missionaries stepped ashore at Mombasa. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: a Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: A Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966 Azizeddin Tejpar University of Central Florida Part of the African History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Tejpar, Azizeddin, "The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: A Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6324. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6324 THE MIGRATION OF INDIANS TO EASTERN AFRICA: A CASE STUDY OF THE ISMAILI COMMUNITY, 1866-1966 by AZIZEDDIN TEJPAR B.A. Binghamton University 1971 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2019 Major Professor: Yovanna Pineda © 2019 Azizeddin Tejpar ii ABSTRACT Much of the Ismaili settlement in Eastern Africa, together with several other immigrant communities of Indian origin, took place in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries. This thesis argues that the primary mover of the migration were the edicts, or Farmans, of the Ismaili spiritual leader. They were instrumental in motivating Ismailis to go to East Africa. -

Toposheet of the Side Plan , Taluka & Dist

Toposheet of The Side Plan , Taluka & Dist. District : Jamnagar For official use only Location Map COMMISSIONERATE OF GEOLOGY AND MINING Industries and Mines Department, Government of Gujarat Legend: District Boundary " District Headquarter ± Mud flat BANAS KANTHA Area : 14125 Sq.km Area under forest : 382.63 Sq.km No. of Talukas : 10 MAHESANA PATAN No. of Villages : 756 SABAR KANTHA KACHCHH No. of Towns : 10 Total Population : 1904278 GANDHINAGAR Male Population : 981320 PANCH MAHALS AHMEDABAD Female Population : 922958 KHEDA DOHAD SURENDRANAGAR " ANAND RAJKOT VADODARA JAMNAGAR BHARUCH NARMADA PORBANDAR BHAVNAGAR AMRELI JUNAGADH SURAT NAVSARI THE DANGS VALSAD Location Index: INDIA GUJARAT Gujarat District : Jamnagar External boundaries are not authenticated * Maps are not to the Scale Prepared by: 1 ISO 9001:2000 For official use only District : Jamnagar Geological Map COMMISSIONERATE OF GEOLOGY AND MINING Industries and Mines Department, Government of Gujarat The Map shows information regarding geological formations of different ages and their respective lithology. Geology: LITHOLOGY AGE ALLUVIUM BLOWN SAND RECENT- HOLOCENE MILIOLITE LIMESTONE PLEISTOCENE JODIYA MIOCENE ! SHALES, MARLS AND SANDSTONES GYPSIFEROUS CLAYS & SANDY LIMESTONES DWARKA BEDS LATERITE AND BAUXITE PALAEOCENE TO EOCENE BASIC INTRUSIVE PALAEOCENE TO UPPER CRETACEOUS DH!ROL TRAP LOWER EOCENE TO UPPER CRETACEOUS "! DIORITES UPPER CRETACEOUS TO PALAEOCENE JAMNAGAR FELSITE,RHYOLITE & PITCHSTONE FLOWS DECCAN TRAP OHKAMANDAL ! LALPUR KHAMBHALIA! ! Legend: ! KALAVAD District Boundary Taluka Boundary KALYANPUR " ! District Headquarter ! Taluka Headquarter B!HANVAD JAMJODHPUR Mudflat ! Location Index: GUJARAT District : Jamnagar ± External boundaries are not authenticated 5 * Maps are not to the Scale Prepared by: ISO 9001:2000 District : Jamnagar For official use only Mineral Map COMMISSIONERATE OF GEOLOGY AND MINING Industries and Mines Department, Government of Gujarat The Map shows information of Mineral occurances of Jamnagar District.