Pauline Hall Laughs out Loud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nordahl Rolfsens Lesebok Fra 1892

AVH505 DET TEOLOGISKE MENIGHETSFAKULTET Siw Fjelstad Foto fra leseboken, s 100; Jesus og barnet av Carl Bloch NORDAHL ROLFSENS LESEBOK FRA 1892 - dannelse til selvstendighet i et fellesskap AVH505 (60 ECTS) våren 2012 Erfaringsbasert master RLE/ Religion og etikk Veileder: Sverre Dag Mogstad Innholdsfortegnelse Innledning / s 4 Del 1. Studien – dens begrunnelse og forankring 1.1 “- nasjonsbygger, og identitet ville han bygge ved å gi en felles landkjenning ” / s 5 1.2 Se seg tilbake for å finne veien fram / s 6 1.3 Den generelle læreplanen i L97 og arven etter Rolfsens lesebok / s 8 1.4 Typisk norsk å være god – men det stemte ikke helt / s 10 1.5 Nordahl Rolfsens lesebok i denne studien / s 12 1.6 Metode og oppbygging / s 15 1.7 Kilder til Rolfsens lesebok og samtid / s 22 1.8 Kilder til teorier om identitet og dannelse / s 25 Del 2. Lesebokens forfatter og lesebokens kontekst 2.1 Familie og oppvekst / s 29 2.2 Rolfsen i møte med en annerledes skole / s 31 2.3 Rolfsen oversetter barnelitteratur / s 32 2.4 Rolfsen og Bjørnson; to menn av samme tid? / s 33 2.5 Dikter i en gullalder / s 35 2.6 En dikter uverdig skolen? / s 36 2.7 Teaterstykket som ble en suksess og et hinder; Svein Uræd / s 37 2.8 Søknaden, en programerklæring? / s 39 2.9 Litteraturen og skolen i Norge i forkant av leseboken / s 40 2.10 Grundtvig og grundtvigianismen / s 43 2.11 Finland / s 45 2.12 Lysakerkretsen / s 49 2.13 Ernst Sars og det moderne gjennombruddet / s 52 2 Del 3. -

CHAN 9985 BOOK.Qxd 10/5/07 5:14 Pm Page 2

CHAN 9985 Front.qxd 10/5/07 4:50 pm Page 1 CHAN 9985 CHANDOS CHAN 9985 BOOK.qxd 10/5/07 5:14 pm Page 2 Edvard Grieg (1843–1907) Poetic Tone-Pictures, Op. 3 11:45 1 1 Allegro ma non troppo 1:52 2 2 Allegro cantabile 2:19 3 3 Con moto 1:55 4 4 Andante con sentimento 3:17 Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht 5 5 Allegro moderato – Vivo 1:16 6 6 Allegro scherzando 0:49 Sonata, Op. 7 19:41 in E minor • in e-Moll • en mi mineur 7 I Allegro moderato – Allegro molto 4:43 8 II Andante molto – L’istesso tempo 4:54 9 III Alla Menuetto, ma poco più lento 3:26 10 IV Finale. Molto allegro – Presto 6:25 Seven fugues for piano (1861–62) 13:29 11 Fuga a 2. Allegro 1:01 in C minor • in c-Moll • en ut mineur 12 [Fuga a 2] 1:07 in C major • in C-Dur • en ut majeur 13 Fuga a 3. Andante non troppo 2:11 Edvard Grieg in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur 14 Fuga a 3. Allegro 1:09 in A minor • in a-Moll • en la mineur 3 CHAN 9985 BOOK.qxd 10/5/07 5:14 pm Page 4 Grieg: Sonata, Op. 7 etc. 15 Fuga a 4. Allegro non troppo 2:36 There were two principal strands in Edvard there, and he was followed by an entire in G minor • in g-Moll • en sol mineur Grieg’s creative personality: the piano and cohort of composers-to-be, among them 16 Fuga a 3 voci. -

Felix' Exam Essay

Kurs: Examensarbete, kandidat, jazz BG1016 15 hp 2015 Konstnärlig kandidatexamen i musik 180 hp Institutionen för jazz Handledare: Sven Berggren Felix Tvedegaard Heim Felix’ Exam Essay Skriftlig reflektion inom självständigt, konstnärligt arbete Det självständiga, konstnärliga arbetet finns dokumenterat på inspelning: CD Innehållsförteckning Musical background .............................................................................................. 2 Project description ................................................................................................. 5 Process .................................................................................................................... 6 Choosing band members ........................................................................................................... 8 Rehearsing ................................................................................................................................ 9 Poster layout and concert program ......................................................................................... 10 Outcome ................................................................................................................ 13 Solo pieces for piano ............................................................................................................... 15 Reflection .............................................................................................................. 18 1 Musical background I grew up in Bergen, Norway, with a lot of music -

A List of Symphonies the First Seven: 1

A List of Symphonies The First Seven: 1. Anton Webern, Symphonie, Op. 21 2. Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 2 3. Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 4 4. Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. 5 5. Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 8 6. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 2 op. 38b 7. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 1 op. 9b The Others: Stefan Wolpe, Symphony No. 1 Matthijs Vermeulen, Symphony No. 6 (“Les Minutes heureuses”) Allan Pettersson, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 6, Symphony No. 8, Symphony No. 13 Wallingford Riegger, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 3 Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2 Alain Bancquart, Symphonie n° 1, Symphonie n° 5 (“Partage de midi” de Paul Claudel) Hanns Eisler, Kammer-Sinfonie Günter Kochan, Sinfonie Nr.3 (In Memoriam Hanns Eisler), Sinfonie Nr.4 Ross Lee Finney, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Darius Milhaud, Symphony No. 8 (“Rhodanienne”, Op. 362: Avec mystère et violence) Gian Francesco Malipiero, Symphony No. 9 ("dell'ahimé"), Symphony No. 10 ("Atropo"), & Symphony No. 11 ("Della Cornamuse") Roberto Gerhard, Symphony No. 1, No. 2 ("Metamorphoses") & No. 4 (“New York”) E.J. Moeran, Symphony in g minor Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 9 Edison Denisov, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2; Chamber Symphony No. 1 (1982) Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 1 Sir Edward Elgar, Symphony No. 2, Symphony No. 1 Frank Corcoran, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Ernst Krenek, Symphony No. 5 Erwin Schulhoff, Symphony No. 1 Gerd Domhardt, Sinfonie Nr.2 Alvin Etler, Symphony No. 1 Meyer Kupferman, Symphony No. 4 Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. -

Norway – Music and Musical Life

Norway2BOOK.book Page 273 Thursday, August 21, 2008 11:35 PM Chapter 18 Norway – Music and Musical Life Chapter 18 Norway – Music and Musical Life By Arvid Vollsnes Through all the centuries of documented Norwegian music it has been obvi- ous that there were strong connections to European cultural life. But from the 14th to the 19th century Norway was considered by other Europeans to be remote and belonging to the backwaters of Europe. Some daring travel- ers came in the Romantic era, and one of them wrote: The fantastic pillars and arches of fairy folk-lore may still be descried in the deep secluded glens of Thelemarken, undefaced with stucco, not propped by unsightly modern buttress. The harp of popular minstrelsy – though it hangs mouldering and mildewed with infrequency of use, its strings unbraced for want of cunning hands that can tune and strike them as the Scalds of Eld – may still now and then be heard sending forth its simple music. Sometimes this assumes the shape of a soothing lullaby to the sleep- ing babe, or an artless ballad of love-lorn swains, or an arch satire on rustic doings and foibles. Sometimes it swells into a symphony descriptive of the descent of Odin; or, in somewhat less Pindaric, and more Dibdin strain, it recounts the deeds of the rollicking, death-despising Vikings; while, anon, its numbers rise and fall with mysterious cadence as it strives to give a local habitation and a name to the dimly seen forms and antic pranks of the hol- low-backed Huldra crew.” (From The Oxonian in Thelemarken, or Notes of Travel in South-Western Norway in the Summers of 1856 and 1857, written by Frederick Metcalfe, Lincoln College, Oxford.) This was a typical Romantic way of describing a foreign culture. -

The History and Revival of the Meråker Clarinet

MOT 2016 ombrukket 4.qxp_Layout 1 03.02.2017 15.49 Side 81 “I saw it on the telly” – The history and revival of the Meråker clarinet Bjørn Aksdal Introduction One of the most popular TV-programmes in Norway over the last 40 years has been the weekly magazine “Norge Rundt” (Around Norway).1 Each half-hour programme contains reports from different parts of Norway, made locally by the regional offices of NRK, the Norwegian state broad- casting company. In 1981, a report was presented from the parish of Meråker in the county of Nord-Trøndelag, where a 69-year old local fiddler by the name of Harald Gilland (1912–1992), played a whistle or flute-like instrument, which he had made himself. He called the instrument a “fløit” (flute, whistle), but it sounded more like a kind of home-made clarinet. When the instrument was pictured in close-up, it was possible to see that a single reed was fastened to the blown end (mouth-piece). This made me curious, because there was no information about any other corresponding instrument in living tradition in Norway. Shortly afterwards, I contacted Harald Gilland, and we arranged that I should come to Meråker a few days later and pay him a visit. The parish of Meråker has around 2900 inhabitants and is situated ca. 80 km northeast of Trondheim, close to the Swedish border and the county of Jamtlandia. Harald Gilland was born in a place called Stordalen in the 1. The first programme in this series was sent on October 2nd 1976. -

Orchestral Music Vol. I1

BIS-CD-1632BIS-CD-1522 FARTEIN VALEN · ORCHESTRALORCHESTRAL MUSICMUSIC VOL.VOL. I1 1 ELISE BÅTNES violin · STAVANGER SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA · CHRISTIAN EGGEN FARTEIN VALEN, portrait by AGNES HIORTH FrontFront cover: cover: Rosa Rosa Centifolia Lutea byby MaryMary Lawrance,Lawrance, from from ‘A ‘A Collection Collection of ofRoses Roses from from Nature’, Nature’, 1799, 1799, London. London. The Royal Horticultural Society, Lindley Library, London. ReproducedReproduced byby kindkind permission.permisson. BIS-CD-1632_f-b.indd 1 08-06-26 16.41.44 BIS-CD-1632 Valen:booklet 17/6/08 09:31 Page 2 VALEN, Fartein (1887–1952) 1 Nenia, Op. 18 No. 1 (1932–33) 4'52 2 An die Hoffnung, Op. 18 No. 2 (1933) 5'50 3 Epithalamion, Op. 19 (1933) 5'54 Symphony No. 2, Op. 40 (1941–44) 23'25 4 I. Allegro con brio 6'29 5 II. Adagio 9'46 6 III. Allegretto 2'14 7 IV. Finale. Allegro molto 4'43 Symphony No. 3, Op. 41 (1944–46) 20'24 8 I. Allegro moderato 7'06 9 II. Larghetto 7'15 10 III. Intermezzo. Allegro 2'10 11 IV. Finale. Allegro 3'36 TT: 61'49 Stavanger Symphony Orchestra Christian Eggen conductor All works published by Harald Lyche & Co’s Musikkforlag 2 BIS-CD-1632 Valen:booklet 17/6/08 09:31 Page 3 artein Valen made his début as a com - which has elements of their espressivo. poser in the Norwegian capital of Oslo in The three single-movement orchestral pieces F1908 with a late romantic piece for the recorded here were written in the space of just piano, Legend, which he had written earlier that over a year and all have connections with Valen’s year. -

Booklet Notes: Arvid O

V A L E N E G G E H V OSLEF VALENTRIO V A L E N T R I O aspekter. Ett av dem er klangen. Fiolin og samtid, lite spilt i dag, dessverre. Men de familiens gård i Valevåg og brukte arbeidet cello gir muligheter for strykerklang i et bredt kan gjenoppdages – sammen med trioer av med trioen som utforsking også av det han register. Klaver gir oss også et stort omfang, Catharinus Elling, Gerhard Schjelderup og kalte «det nye kontrapunkt» – en moderne og sammen kan de lage så mange ulike ut- Sigurd Lie. musikk bygget på tradisjonelt kontrapunkt en trykk gjennom melodisk, harmonisk og klang- (Bach) kombinert med en mer moderne lig behandling, og ikke minst ved hele bredden tonalitet (som hos Max Reger), som skulle gå trio i artikulasjon, frasering og uttrykk. Trioen kan over i atonalt kontrapunkt. trioer klinge stort og mektig, og intimt, andre ganger FARTEIN VALEN (1887–1952) spenne fra det slagverksaktige over plastiske TRIO FOR FIOLIN, CELLO OG KLAVER For hver dag blir jeg mere og mere viss paa at det MODERATO VALEN er det eneste rigtige for mig, men det er jo et langt melodier og linjer til glassklare flageoletter. SCHERZO. ALLEGRO EGGE lerred at bleke. Trioen gaar det uendelig langsomt LARGO HVOSLEF Men også trioens hovedhensikter har vært FINALE. ALLEGRO MOLTO med, men jeg har ikke tapt modet. Schönbergs mangfoldige. Vi husker Haydns og Mozarts orkester-stykker har jeg faat og natten efter sov divertissementer og Beethovens dobbelt- (jeg) ikke vor Aufregung. Han er kommet saa uen- delig langt, uendelig meget længer en det vi tuller I denne produksjonen er det valgt tre trioer fra het. -

6. KUNDENE OG KONTAKTENE Kundekatalogen – Sosiale Grupper, Kjønn, Alder, Geografi

Kari Michelsen: HUSET WARMUTH Kapittel 6: Kunder og kontakter 6. KUNDENE OG KONTAKTENE Kundekatalogen – sosiale grupper, kjønn, alder, geografi Firma Warmuth førte protokoll over forsendelsene til sine kunder. Protokollen for perioden 1893-96 oppbevares på Nasjonalbiblioteket i Oslo. Den omfatter bare forsendelser – ikke kjøp direkte fra butikken. Protokollen, eller vareforsendelseskatalogen som forleggeren kalte den, er på ca. 400 sider à 37 navn, dvs. den inneholder totalt ca. 15.000 navn – der en god del nevnes flere ganger. Forsendelsesmåtene var pr. brev, pr. pakke, pr. jernbane eller (til Vest- og Sørlandet) pr. skip. Det står intet om hva kundene hadde kjøpt, bare vekten på forsendelsen. Vekten alene kan ikke fortelle noe om innholdet – enten det for eksempel var en stor notebunke eller et lite instrument. Av disse ca. 15.000 har jeg tatt ut 978 tilfeldige navn til gransking der 485 navn har latt seg entydig identifisere i folketellingen 1900. Sosiale grupper: Av de 485 navn er 36 sosialt uidentifisert. De gjenstående 449 fordeler seg slik: Gruppe Antall % I 10 høyere embetsstand 2,2 II 124 lavere embetsstand 27,8 III 266 handelsstand og håndverkere 59,3 IV 28 bønder 6,1 V 15 arbeidere, fiskere, sjøfolk 3,3 VI 6 foreninger, skoler 1,3 69 Kari Michelsen: HUSET WARMUTH Kapittel 6: Kunder og kontakter Handels- og håndverkerstanden dominerer overlegent med sine nær 60 %. Musikerne ble hovedsakelig rekruttert fra dette sjiktet. Den lavere embetsstand teller halvparten av denne gruppen og de øvrige gruppene er helt små. Samfunnsutviklingen, med vekst i folketallet – særlig i byene og ikke minst i Christiania – gjennom siste del av 1800- årene gjorde det mulig for driftige håndverkere og handelsmenn å slå seg opp. -

The Congress for Cultural Freedom, La Musica Nel Xx Secolo, And

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2012 The onC gress for Cultural Freedom, La Musica Nel XX Secolo, and Aesthetic "Othering": An Archival Investigation Shannon E. Pahl University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pahl, Shannon E., "The onC gress for Cultural Freedom, La Musica Nel XX Secolo, and Aesthetic "Othering": An Archival Investigation" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 40. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/40 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONGRESS FOR CULTURAL FREEDOM, LA MUSICA NEL XX SECOLO, AND AESTHETIC “OTHERING”: AN ARCHIVAL INVESTIGATION by Shannon E. Pahl A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2012 ABSTRACT THE CONGRESS FOR CULTURAL FREEDOM, LA MUSICA NEL XX SECOLO, AND AESTHETIC “OTHERING”: AN ARCHIVAL INVESTIGATION by Shannon E. Pahl The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2012 Under the Supervision of Professor Dr. Gillian Rodger Between 1950 and 1967, the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an organiZation of anti- totalitarian intellectuals funded by the United States government, hosted conferences and festivals regarding the pursuit of intellectual freedom. In 1952 and 1954, the Congress for Cultural Freedom hosted two music events. While the first festival has been researched considerably, the 1954 conference has not been documented comparably. -

1 Musiikkikohtaamisia Pohjolassa Ja Metropoleissa Helena Tyrväinen 1800-Luvun Viimeisinä Vuosikymmeninä Pohjoismaiden Kirj

2016, Musiikkikohtaamisia Pohjolassa ja metropoleissa / Musikaliska möten i Norden och metropolerna. In: Jussi Nuorteva, Päivi Happonen & John StrömberG (toim. / red.), Pro Finlandia. Suomen tie itsenäisyyteen 3. Näkökulma: Ruotsi, Tanska, Norja ja Islanti / Pro Finlandia. Finlands väg till självständighet 3. Synvinkel: Sverige, Danmark, Norge oCh Island. Helsinki: Kansallisarkisto & Edita. S. 281–293. Musiikkikohtaamisia Pohjolassa ja metropoleissa Helena Tyrväinen 1800-luvun viimeisinä vuosikymmeninä Pohjoismaiden kirjallisuus ja taide, musiikki mukaan lukien, olivat aikakauden keskeinen kulttuuri-ilmiö ja kansainvälisen kiinnostuksen kohde. Kontaktit kyseisiin virtauksiin antoivat kantovoimaa Suomen säveltaiteen nousulle kohti sen kansallisromanttista kultakautta. Suomen ja muiden Pohjoismaiden välillä oli vanhastaan suoria musiikkiyhteyksiä. Ne olivat arvokkaita suomalaistaiteilijoiden koulutetulle parhaimmistolle ajankohtana, jona kotimaan musiikki-instituutiot olivat kehittymättömiä ja ammatinharjoituksen näköalat kapeita. Suomalaisen oopperan toiminta käynnistyi 1873, mutta loppui 1879 rahavaikeuksiin ja kieliryhmien kiistoihin yli kolmeksikymmeneksi vuodeksi. HelsinGin orkesteriyhdistyksen orkesteri ja Musiikki-instituutti (nykyiset HelsinGin kaupunginorkesteri ja Sibelius-Akatemia) perustettin 1882. Vuosisadan kääntyessä kohti loppuaan pohjoismaista vuorovaikutusta ruokkivat musiikkielämän kansainvälistyminen ja taiteilijakohtaamiset Euroopan suurissa keskuksissa. Edvard Grieg (1843–1907), Norjan elinvoimaisen säveltaiteen keulakuva, -

Tilbudsliste Nr

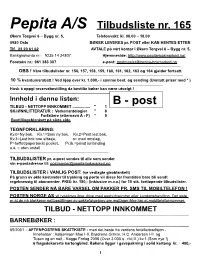

Pepita A/S Tilbudsliste nr. 165 Økern Torgvei 6 – Bygg nr. 5, Telefonvakt: kl. 08.00 – 18.00 0580 Oslo BØKER LEVERES pr. POST eller KAN HENTES ETTER Tlf. 22 20 61 62 AVTALE på vårt kontor i Økern Torgvei 6 – Bygg nr. 5, Bankgirokonto nr.: 9235 14 34807 Hjemmeside: http://www.pepita-bokmarked.no/ Foretaks nr.: 961 383 307 e-post: [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ OBS ! Våre tilbudslister nr. 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163 og 164 gjelder fortsatt. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 % kvantumsrabatt ! Ved kjøp over kr. 1.000,- i samme best. og sending (Unntatt priser med * ) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Husk å oppgi reservebestilling da bestilte bøker kan være utsolgt ! ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Innhold i denne listen: B - post TILBUD - NETTOPP INNKOMMET ................ " 1 SKJØNNLITTERATUR : Verker/antologier " 8 Forfattere (etternavn A - F) ” 9 Bestillingsblankett på siste side