The Incarceration of the Chiricahua Apaches, 1886-1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Mari Sandoz, Custer, and the Indian Wars"

Summer 2016 Issue "Mari Sandoz, Custer, and the Indian Wars" “Mari Sandoz, Custer, and the Indian Wars” is the theme of the 2016 Pilster Lecture on October 13 at the Chadron State College Student Center. Paul Andrew Hutton, Distinguished Professor of History at the University of New Mexico is the guest speaker for this annual event sponsored by the Mari Sandoz Heritage Society and supported by the Esther and Raleigh Pilster Endowment. The mission of the lecture series is to bring speakers of national renown to the Chadron State College campus for the benefit of the college and residents of the high plains of Western Nebraska. The 7:30 pm MT lecture is free to the public. A reception and book signing will be held following the lecture at the CSC Student Center. Hutton has published widely in both scholarly and popular magazines, and is a five‐time winner of the Western Writers of America Spur Award and six‐time winner of the Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum for his print and film writing. His Phil Sheridan and His Army (1985) received the Billington Prize from the Organization of American Historians, the Evans Biography Award, and the Spur Award from the Western Writers of America. He is also the editor of Western Heritage (2011), Roundup (2010), Frontier and Region (1997), The Custer Reader (1992), Soldiers West (1987), and the ten‐volume Eyewitness to the Civil War series from Bantam Books (1991‐1993). From 1977 to 1984 he was associate editor of the Western Historical Quarterly, from 1985 to 1991 was editor of the New Mexico Historical Review, and from 1990‐2006 served as Executive Director of the Western History Association. -

Chiricahuas Present a Verdant, Forested Island in a Sea of Desert

Rising steeply from the dry grasslands of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, the Chiricahuas present a verdant, forested island in a sea of desert. Many species of trees, shrubs, and flowering herbs clothe steep canyon walls. Shady glens, alive with birds, are sheltered by rows of strange massive spires, turrets, and battlements in this fascinating wonderland of rocks. Story of the rocks-What geological forces created these striking and peculiar pinnacles and balanced rocks? Geolo- gists explain that millions of years ago volcanic activity was extensive throughout this region. A series of explosive eruptions, alternating with periods of inactivity, covered the area with layers of white-hot volcanic ash that welded into rock. Because the eruptions varied in magnitude, the deposits were of different thicknesses. Finally, the eruptions ceased, followed by movements in the earth's crust which slowly lifted and tilted great rock masses to form mountains. The stresses responsible for the movements caused a definite pattern of cracks. Along the vertical cracks and planes of horizontal weakness, ero- sion by weathering and running water began its persistent work. Cracks were widened to form fissures; and fissures grew to breaches. At the same time, under-cutting slowly took place. Gradually the lava masses were cut by millions of ero- sional channels into blocks of myriad sizes and shapes, to be further sculptured by the elements. Shallow canyons became deeper and more rugged as time passed. Weathered rock formed soil, which collected in pockets; and plants thus gained a foothold. Erosion is still going on slowly and persistently among the great pillared cliffs of the monument. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

Fort Bowie U.S

National Park Service Fort Bowie U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Bowie National Historic Site The Chiricahua Apaches Introduction The origin of the name "Apache" probably stems from the Zuni "apachu". Apaches in fact referred to themselves with variants of "nde", simply meaning "the people". By 1850, Apache culture was a blend of influences from the peoples of the Great Plains, Great Basin, and the Southwest, particularly the Pueblos, and as time progressed—Spanish, Mexican, and the recently arriving American settler. The Apache Tribes Chiricahua speak an Athabaskan language, relating Geronimo was a member of the Bedonkohe, who them to tribes of western Canada. Migration from were closely related to the Chihenne (sometimes this region brought them to the southern plains by referred to as the Mimbres); famous leaders of the 1300, and into areas of the present-day American band included Mangas Coloradas and Victorio. Southwest and northwestern Mexico by 1500. This The Nehdni primarily dwelled in northern migration coincided with a northward thrust of Mexico under the leadership of Tuh. the Spanish into the Rio Grande and San Pedro Valleys. Cochise was a Chokonen Chiricahua leader who rose to leadership around 1856. The Chockonen Chiricahuas of southern Arizona and New primarily resided in the area of Apache Pass and Mexico were further subdivided into four bands: the Dragoon Mountains to the west. Bedonkohe, Chokonen, Chihenne, and Nehdni. Their total population ranged from 1,000 to 1,500 people. Organization and Apache population was thinly spread, scattered of Apache government and was the position that Family Life into small groups across large territories, tribal chiefs such as Cochise held. -

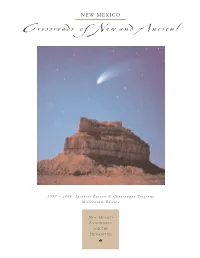

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am

American Indian Law Review Volume 35 | Number 1 1-1-2010 Values in Transition: The hirC icahua Apache from 1886-1914 John W. Ragsdale Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation John W. Ragsdale Jr., Values in Transition: The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am. Indian L. Rev. (2010), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol35/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VALUES IN TRANSITION: THE CHIRICAHUA APACHE FROM 1886-1914 John W Ragsdale, Jr.* Abstract Law confirms but seldom determines the course of a society. Values and beliefs, instead, are the true polestars, incrementally implemented by the laws, customs, and policies. The Chiricahua Apache, a tribal society of hunters, gatherers, and raiders in the mountains and deserts of the Southwest, were squeezed between the growing populations and economies of the United States and Mexico. Raiding brought response, reprisal, and ultimately confinement at the loathsome San Carlos Reservation. Though most Chiricahua submitted to the beginnings of assimilation, a number of the hardiest and least malleable did not. Periodic breakouts, wild raids through New Mexico and Arizona, and a labyrinthian, nearly impenetrable sanctuary in the Sierra Madre led the United States to an extraordinary and unprincipled overreaction. -

AL SIEBER, FAMOUS SCOUT of the SOUTHWEST (By DAN R

Al Sieber, Famous Scout Item Type text; Article Authors Williamson, Dan R. Publisher Arizona State Historian (Phoenix, AZ) Journal Arizona Historical Review Rights This content is in the public domain. Download date 29/09/2021 08:22:29 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623491 60 ARIZONA HISTORICAL REVIEW AL SIEBER, FAMOUS SCOUT OF THE SOUTHWEST (By DAN R. WILLIAMSON) Albert Sieber was born in the Grand Dutchy of Baden, Ger- many, February 29, '1844, and died near Roosevelt, Arizona, February 19, 1907. Came to America with his parents as a small boy, settling for a time in Pennsylvania, then moved to Minnesota. Early in 1862 Sieber enlisted in Company B, First Minne- sota Volunteer Infantry, serving through the strenuous Penin- sula campaign of the Army of the Potomac as a corporal and a sharp-shooter. On July 2, 1863, on Gettysburg Battlefield, he was dangerously wounded in the head by a piece of shell, and while lying helpless and unattended on the field of battle a bul- let entered his right ankle and followed up the leg, coming out at the knee. He lay in the hospital until December, 1863, when he was transferred to the First Regiment of Veteran Reserves as a corporal, under Captain Morrison, and his regiment was ac- credited to the State of Massachusetts. When Sieber fell wound- ed on the field of Gettysburg, General Hancock, who was near him, was wounded at the same time. For Sieber 's service with this regiment the State of Massachusetts paid him the sum of $300 bounty. -

United States Army Scouts: the Southwestern

3-/71 UNITED STATES ARMY SCOUTS: THE SOUTHWESTERN EXPERIENCE, 1866-1890 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Carol Conley Nance, B. A. Denton, Texas May, 1975 Nance, Carol Conley, United States Army Scouts: The Southwestern Experience, 1866-1890. Master of Arts (History), May, 1975, 156 pp., 4 maps, bibliography, 107 titles. In the post-Civil War Southwest, the United States Army utilized civilians and Indians as scouts. As the mainstay of the reconnaissance force, enlisted Indians excelled as trackers, guides, and fighters. General George Crook became the foremost advocate of this service. A little-known aspect of the era was the international controversy created by the activities of native trackers under the 1882 recipro- cal hot pursuit agreement between Mexico and the United States. Providing valuable information on Army scouts are numerous government records which include the Annual Report of the Secretary of War from 1866 to 1896 and Foreign Relations of the United States for 1883 and 1886. Memoirs, biographies, and articles in regional and national histori- cal journals supplement government documents. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS . iv Chapter I. THE SOUTHWEST: CONVENTIONAL ARMY, UNCONVENTIONAL ENEMY 17 II. ARMY SCOUTS: CIVILIANS ON THE TRAIL . 2.17 III. ARMY SCOUTS: SET AN INDIAN TO CATCH AN INDIAN ..................... - - - - 28 IV. GENERAL GEORGE CROOK: UNCONVENTIONAL SOLDIER ........................ - -0 -0 -0 .0 68 V. INDIAN SCOUTS: AN INTERNATIONAL CONTROVERSY .......... *........ .100 VI. ARMY SCOUTS: SOME OBSERVATIONS .. o. 142 BIBLIOGRAPHY, . ...........-.-.-. .148 iii LIST OF MAPS Map Following Page 1. -

![CHIRICAHUA LEOPARD FROG (Lithobates [Rana] Chiricahuensis)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9108/chiricahua-leopard-frog-lithobates-rana-chiricahuensis-669108.webp)

CHIRICAHUA LEOPARD FROG (Lithobates [Rana] Chiricahuensis)

CHIRICAHUA LEOPARD FROG (Lithobates [Rana] chiricahuensis) Chiricahua Leopard Frog from Sycamore Canyon, Coronado National Forest, Arizona Photograph by Jim Rorabaugh, USFWS CONSIDERATIONS FOR MAKING EFFECTS DETERMINATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REDUCING AND AVOIDING ADVERSE EFFECTS Developed by the Southwest Endangered Species Act Team, an affiliate of the Southwest Strategy Funded by U.S. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program December 2008 (Updated August 31, 2009) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document was developed by members of the Southwest Endangered Species Act (SWESA) Team comprised of representatives from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (BoR), Department of Defense (DoD), Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), U.S. Forest Service (USFS), U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), National Park Service (NPS) and U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Dr. Terry L. Myers gathered and synthesized much of the information for this document. The SWESA Team would especially like to thank Mr. Steve Sekscienski, U.S. Army Environmental Center, DoD, for obtaining the funds needed for this project, and Dr. Patricia Zenone, USFWS, New Mexico Ecological Services Field Office, for serving as the Contracting Officer’s Representative for this grant. Overall guidance, review, and editing of the document was provided by the CMED Subgroup of the SWESA Team, consisting of: Art Coykendall (BoR), John Nystedt (USFWS), Patricia Zenone (USFWS), Robert L. Palmer (DoD, U.S. Navy), Vicki Herren (BLM), Wade Eakle (USACE), and Ronnie Maes (USFS). The cooperation of many individuals facilitated this effort, including: USFWS: Jim Rorabaugh, Jennifer Graves, Debra Bills, Shaula Hedwall, Melissa Kreutzian, Marilyn Myers, Michelle Christman, Joel Lusk, Harold Namminga; USFS: Mike Rotonda, Susan Lee, Bryce Rickel, Linda WhiteTrifaro; USACE: Ron Fowler, Robert Dummer; BLM: Ted Cordery, Marikay Ramsey; BoR: Robert Clarkson; DoD, U.S. -

In the Land of the Mountain Gods: Ethnotrauma and Exile Among the Apaches of the American Southwest

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 10 Issue 1 Article 6 6-3-2016 In the Land of the Mountain Gods: Ethnotrauma and Exile among the Apaches of the American Southwest M. Grace Hunt Watkinson Arizona State University at the Tempe Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Hunt Watkinson, M. Grace (2016) "In the Land of the Mountain Gods: Ethnotrauma and Exile among the Apaches of the American Southwest," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 10: Iss. 1: 30-43. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.10.1.1279 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol10/iss1/6 This Symposium: Genocide Studies, Colonization, and Indigenous Peoples is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In the Land of the Mountain Gods: Ethnotrauma and Exile Among the Apaches of the American Southwest M. Grace Hunt Watkinson Arizona State University Tempe, AZ, USA Abstract: In the mid to late nineteenth century, two Indigenous groups of New Mexico territory, the Mescalero and the Chiricahua Apaches, faced violence, imprisonment, and exile. During a century of settler influx, territorial changeovers, vigilante violence, and Indian removal, these two cousin tribes withstood an experience beyond individual pain best described as ethnotrauma. Rooted in racial persecution and mass violence, this ethnotrauma possessed layers of traumatic reaction that not only revolved around their ethnicity, but around their relationship with their home lands as well. -

Geronimo's Story of His Life

Geronimo’s Story of His Life Taken Down and Edited by S. M. BARRETT Superintendent of Education, Lawton, Oklahoma DIGITAL REPRINT Elegant Ebooks COPYRIGHT INFORMATION Book: Geronimo’s Story of His Life Authors: Geronimo, 1829–1909 S. M. (Stephen Melvil) Barrett, 1865–? First published: 1906 The original book is in the public domain in the United States and in some other countries as well. However, it is unknown when S. M. Barrett died. Depending on the year of his death, the book may still be under copyright in countries that use the life of the author + 70 years (or more) for the duration of copyright. Readers outside the United States should check their own countries’ copyright laws to be certain they can legally download this ebook. The Online Books Page has an FAQ which gives a summary of copyright durations for many other countries, as well as links to more official sources. This PDF ebook was created by José Menéndez. NOTE ON THE TEXT The text and illustrations used in this ebook are from a photographic reprint of the 1906 first edition. A number of typographical errors in the paper book have been corrected, but to preserve all of the original book, the misprints are included in footnotes signed “J.M.” The line breaks and pagination of the original book have also been reproduced. In addition, a few endnotes (also signed “J.M.”) have been added to point out some other errors and inconsistencies in the original book. I would like to express my thanks to Mr. Lenny Silverman at the New Mexico State University Library’s Archives and Special Collections department for providing me with several page scans from NMSU’s copy of the 1907 edition. -

U.S. Army Military History Institute Indian Wars-Southwest 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 16 Dec 2011

U.S. Army Military History Institute Indian Wars-Southwest 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 16 Dec 2011 APACHE WARS A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources CONTENTS General Sources.....p.1 Pre-1861.....p.3 Apache Pass (Feb 1861).....p.4 Mimbres Apaches.....p.4 1860s - (Cochise, Mangas).....p.5 1870-75 (Reservation Roundup).....p.5 1876-86 (Geronimo).....p.6 Prisoners in the East.....p.10 GENERAL/MISCELLANEOUS Altshuler, Constance W. Chains of Command: Arizona and the Army, 1856-1875. Tucson, AZ: AZ Historical Society, 1981. 280 p. UA26.A7.A45. Baldwin, Gordon C. The Warrior Apaches: A Story of the Chiricahua and Western Apache. Tucson, AZ: King, 1965. 144 p. E99.A6.B15. Barnes, William C. Apaches and Longhorns. Los Angeles: Ward Ritchie, 1941. F811.B27. Bell, William G. “Field Commander vs. Washington Negotiator in Apacheland.” Army (Feb 2001): pp. 68-70, 72 & 74. Per. Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip. (John S.). Massacre at Camp Grant: Forgetting and Remembering Apache History. Tucson, AZ: U AZ, 2007. 159 p. E99.A6.C66. Cornell, Charles T. "Apache, Past and Present." Tucson Citizen (May/Jul 1921). Order of the Indian Wars Coll-File-A-4-Arch. Cozzens, Peter, editor. Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890. Vol. 1: The Struggle for Apacheria. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 2001. E81.E94. Cruse, Thomas. Apache Days and After. Caldwell, ID: Caxton, 1941. E83.866.C95. Apache Wars p.2 Gaston, J.A. "Cavalry Officer on the Frontier." Typescript carbon, Wash, DC, Dec 1935. 19 p. Order of the Indian Wars Coll-File-G-10-Arch.