RAILS with TRAILS Best Practices and Lessons Learned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Sept 2015 - August 2016 Annual Report 2015-2016

Annual Report Sept 2015 - August 2016 Annual Report 2015-2016 Rail Transportation Program Vision: “Develop leaders and technologies for 21st century rail transportation.” Mission: “To participate in the development of rail transportation and related engineering skills for the 21st century through an interdisciplinary and collaborative program that aligns Michigan Tech faculty and students with the demands of the industry.” 2 Director’s Message One of the easiest tasks for the Michigan Tech’s Rail Transportation Program Director is writing the message for the annual report. We never seem to be short of stories and while much of our work is about consistency from year to year, each one of them also contains highlights that are special for the year in question, and 2015-2016 was no exception. Perhaps the greatest achievement for the year was the approval of our Rail Transportation minor to the university curriculum. The minor follows our RTP vision by being multidisciplinary and flexible and we’re hoping that our first graduate with the minor will be during next academic year. The second special moment of the year took place in mid-August when we hosted the 4th Annual Michigan Rail Conference for the first time in the Upper Peninsula. The conference (held in Marquette with field visits to Escanaba) had a record participation and sponsorship levels and our field trips turned out as an experience beyond belief. For two days, it was great to be a “Yooper railroader”. From the projects/research perspective, we were pleased to have our first two projects with the greatest industry supporter of our program, CN Railway. -

The Laurel Highlands Pennsylvania

The LaureL highLands pennsylvania 2010 Travel Guide a place of WONDER You really should be here! Make New Family Memories Seven Springs Mountain Resort is the perfect place to reconnect and make a new memory with your family and friends! Whether the snow is blanketing the ground, the leaves are gilded in rich autumn hues or the sun is shining and there is a warm summer breeze, Seven Springs is your escape destination. At Pennsylvania’s largest resort, you can unwind at Trillium Spa, take a shot at sporting clays, explore 285 acres of skiable terrain, enjoy the adrenaline rush of a snowmobile tour – the opportunities are endless! At Seven Springs, we strive to provide you and yours with legendary customer service, value and warm lifelong memories. What are you waiting for? You really should be here! Seasonal packages available year-round - call 800.452.2223 or visit us on line at www.7Springs.com. Seven Springs Mountain Resort 777 Waterwheel Drive | Seven Springs, PA 15622 800.452.2223 | www.7Springs.com s you look through the 2010 Laurel AHighlands Travel Guide, you may notice the question, have you ever wondered, used a lot! Have you ever wondered what it would be like to 1won-der: \wən-dər\ n 1 a: a cause of astonishment or admiration: marvel b: miracle 2 : the quality of exciting amazed admiration 3 a : rapt attention or astonishment at something awesomely mysterious or new to one’s experience 2won-der: v won·dered; won·der·ing 1 a : to be in a state of wonder b : to feel surprise 2 : to feelhave curiosity oryou doubt 3 won-derever: adj WONDERED? wondrous, wonderful: as a : exciting amazement or admiration b : effective or efficient far beyond anything previously known or anticipated. -

License Agreement with Gotcha Ride LLC to Operate the North County Coastal Bike Share Pilot Program in the City of Encinitas

MEETING DATE: April 17, 2019 PREPARED BY: Crystal Najera, CAP DEPT. DIRECTOR: Karen P. Brust Program Administrator DEPARTMENT: City Manager CITY MANAGER: Karen P. Brust SUBJECT: License Agreement with Gotcha Ride LLC to operate the North County Coastal Bike Share Pilot Program in the City of Encinitas. RECOMMENDED ACTION: 1) Authorize the City Manager, in consultation with the City Attorney, to execute a license agreement with Gotcha Ride LLC (in substantial form as attached) to operate the North County Coastal Bike Share Pilot Program in the City of Encinitas (Attachment 5). STRATEGIC PLAN: This item is related to the following Strategic Plan focus areas: • Environment—promotes the use of emissions-free bicycles as an alternative mode of transportation. • Transportation—supports a transportation mode that accommodates more people with minimal impact on the community. • Recreation—promotes active lifestyles and community health. • Economic Development—addresses the “last mile” gap between public transit and local businesses and promotes tourism. FISCAL CONSIDERATIONS: There is no fiscal impact associated with the recommendation. Gotcha will bear the sole cost of deploying and operating the bike share program. Minimal City staff time will be needed to coordinate with Gotcha to ensure that the program operates in a manner beneficial to the City. BACKGROUND: Bike share is a service through which bicycles are made available for shared use to individuals on a very short-term basis, allowing them to rent a bicycle at one location and return it either at the same location or at a different location within a defined geographic boundary. Transportation, especially travel via single occupancy vehicle, is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions in Encinitas and the North County coastal region. -

Olathe's Bike Share Implementation Strategy

CITY OF OLATHE + MARC Bike Share Implementation Strategy FEBRUARY 2018 Bike Share Implementation Strategy | 1 2 | City of Olathe Acknowledgements Project Partners Advisory Committee City of Olathe John Andrade – Parks & Recreation Foundation Mid America Regional Council Tim Brady – Olathe Schools Marvin Butler – Fire Captain/Inspector Emily Carrillo – Neighborhood Planning City Staff Coordinator Mike Fields – Community Center Manager Susan Sherman – Assistant City Manager Ashley Follett – Johnson County Department of Michael Meadors – Parks & Recreation Director Health and Enviroment Brad Clay – Deputy Director Parks & Recreation Megan Foreman – Johnson County Department Shawna Davis – Management Intern of Health and Enviroment Lisa Donnelly – Park Project Planner Bubba Goeddert – Olathe Chamber of Commerce Mike Latka – Park Project Coordinator Ben Hart – Parks & Recreation Foundation Linda Voss – Sr. Traffic Engineer Katie Lange – Interpreter Specialist Matt Lee – Mid-America Nazarene University Consultant Team Laurel Lucas – Customer Service, Housing Megan Merryman – Johnson County Parks & BikeWalkKC Recreation District Alta Planning + Design Liz Newman – Sr. Horticulturist Vireo Todd Olmstead – Facility & Housing Assistant Manager Sean Pendley – Sr. Planner Kathy Rankin – Housing Services Manager Bryan Severns – K-State Olathe Jon Spence – Mid-America Nazarene University Drew Stihl – Mid-America Regional Council Brenda Volle – Program Coordinator, Housing Rob Wyrick – Olathe Health Bike Share Implementation Strategy | 3 4 | City of Olathe Table of Contents I. BACKGROUND 11 II. ANALYSIS 15 III. SYSTEM PLANNING 45 IV. IMPLEMENTATION 77 Bike Share Implementation Strategy | 5 6 | City of Olathe Executive Summary Project Goals System Options • Identify how bike share can benefit Olathe. • Bike Library: Bike libraries usually involve a fleet of bicycles that are rented out at a limited • Identify the local demand for bike share in number of staffed kiosks. -

Warner Spur Multi-Use Trail Master Plan

Warner Spur Multi-Use Trail Master Plan Chester County Tredyffrin Township Prepared by: December 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Prepared for the In partnership with Tredyffrin Township Chester County Board of Commissioners Plan Advisory Committee Michelle Kichline Zachary Barner, East Whiteland Township Kathi Cozzone Mahew Baumann, Tredyffrin Township Terence Farrell Les Bear, Indian Run Road Association Stephen Burgo, Tredyffrin Township Carol Clarke, Great Valley Association Consultants Rev. Abigail Crozier Nestlehu, St. Peter's Church McMahon Associates, Inc. Jim Garrison, Vanguard In association with Jeff Goggins, Trammel Crow Advanced GeoServices, Corp. Rachael Griffith, Chester County Planning Commission Glackin Thomas Panzak, Inc. Amanda Lafty, Tredyffrin Township Transportation Management Association of Tim Lander, Open Land Conservancy of Chester County Chester County (TMACC) William Martin, Tredyffrin Township Katherine McGovern, Indian Run Road Association Funding Aravind Pouru, Atwater HOA Dave Stauffer, Chester County Department of Facilities and Parks Grant funding provided from the William Penn Brian Styche, Chester County Planning Commission Foundation through the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission’s Regional Trails Program. Warner Spur Multi-Use Trail Master Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 | Background 3 | Conceptual Improvement Plan Introduction 1-1 Conceptual Improvement Plan 3-1 History and Previous Plans 1-1 Conceptual Design Exhibits for Key 3-8 Connections and Crossings Study Area 1-2 Public and Emergency -

Regional Rail Service the Vermont Way

DRAFT Regional Rail Service The Vermont Way Authored by Christopher Parker and Carl Fowler November 30, 2017 Contents Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 The Budd Car RDC Advantage 5 Project System Description 6 Routes 6 Schedule 7 Major Employers and Markets 8 Commuter vs. Intercity Designation 10 Project Developer 10 Stakeholders 10 Transportation organizations 10 Town and City Governments 11 Colleges and Universities 11 Resorts 11 Host Railroads 11 Vermont Rail Systems 11 New England Central Railroad 12 Amtrak 12 Possible contract operators 12 Dispatching 13 Liability Insurance 13 Tracks and Right-of-Way 15 Upgraded Track 15 Safety: Grade Crossing Upgrades 15 Proposed Standard 16 Upgrades by segment 16 Cost of Upgrades 17 Safety 19 Platforms and Stations 20 Proposed Stations 20 Existing Stations 22 Construction Methods of New Stations 22 Current and Historical Precedents 25 Rail in Vermont 25 Regional Rail Service in the United States 27 New Mexico 27 Maine 27 Oregon 28 Arizona and Rural New York 28 Rural Massachusetts 28 Executive Summary For more than twenty years various studies have responded to a yearning in Vermont for a regional passenger rail service which would connect Vermont towns and cities. This White Paper, commissioned by Champ P3, LLC reviews the opportunities for and obstacles to delivering rail service at a rural scale appropriate for a rural state. Champ P3 is a mission driven public-private partnership modeled on the Eagle P3 which built Denver’s new commuter rail network. Vermont’s two railroads, Vermont Rail System and Genesee & Wyoming, have experience hosting and operating commuter rail service utilizing Budd cars. -

Canadian Rail No162 1965

<:;an..adi J~mnn Number 162 / Janua r y 1965 Cereal box coupons and soap package enclosures do not general ly excite much enthusiasm from the editor of 'Canadian Rail', but we must admit we are looking forward with some eagerness to comp leting our collection of RAILWAY MUGS currently being distribut e d by the Quaker Oats Company, in their specially-marked packages of Quaker Oats. This series of twelve hot chocolate mugs depicts the develop - ment of the steam locomotive in Canada from the 0-6-0 "Samson", to the CPR 2-10-4 #8000. The mugs are being offered by the Quaker Oats Company of Cana da to salute Canada's Centennial, and the part played by the rail ways and their steam locomotives in furthering the pro ~ ress of the nation. Each cup pictures an authentic locomotive design -- one shows a Canadian Northern 2-8-0, a type of locomotive that made a major contribution to the country's prairie economy by moving grain from the Western provinces to the Lakehead -- another shows one of the Canadian Pacific's ubiquitous D-10 engines. There are 12 different locomotives in the series - each a col lector's item. The reproductions are precisely etched in decora tive colours and trimmed with 22k gold. Canadian Rail Par,e 3 &eee_eIPIrWB __waBS} -- E.L.Modler. Once a Ga in this year, the Canadian National Railways has leased a number of road switcher type diesels from the Duluth, Missabe and Iron Range Railroad. :,ihile last year all the uni ts leased from the D.I.L& I.R. -

Primary Contact Organization Information

Application 10350 - 2018 Multiuse Trails and Bicycle Facilities 11025 - Sam Morgan Regional Trail Segment 1 Reconstruction Regional Solicitation - Bicycle and Pedestrian Facilities Status: Submitted Submitted Date: 07/13/2018 2:15 PM Primary Contact Paul Michael Sawyer Name:* Salutation First Name Middle Name Last Name Title: Management Assistant Department: Saint Paul Parks and Recreation Email: [email protected] Address: 25 W 4th St 400 City Hall Annex Saint Paul Minnesota 55102 * City State/Province Postal Code/Zip 651-266-6417 Phone:* Phone Ext. Fax: What Grant Programs are you most interested in? Parks Capital Improvement Program Grants Organization Information Name: ST PAUL, CITY OF Jurisdictional Agency (if different): Organization Type: City Organization Website: Address: Parks and Recreation 400 CITY HALL ANNEX 25 W 4TH ST ST PAUL Minnesota 55102 * City State/Province Postal Code/Zip County: Ramsey 651-266-6400 Phone:* Ext. Fax: PeopleSoft Vendor Number 0000003222A15 Project Information Project Name Sam Morgan Regional Trail Segment 1 Reconstruction Primary County where the Project is Located Ramsey Cities or Townships where the Project is Located: Saint Paul Jurisdictional Agency (If Different than the Applicant): This project proposes to reconstruct sections of the original segment that have reached the end of their usable life of the Sam Morgan Regional Trail along Shepard Rd in Saint Paul. The project will include removing the asphalt and base of the old trail; correcting any grades for drainage and Brief Project Description (Include location, road name/functional accessibility; constructing new base and asphalt; class, type of improvement, etc.) installing audible pedestrian signals and pedestrian ramps at intersections; landscaping; and installing lighting, signage, and user amenities. -

Competitive Issues in the Deregulated United States Railroad Industry

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 11-1-1997 Competitive Issues in the Deregulated United States Railroad Industry Johannes Christian Koeppe University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Koeppe, Johannes Christian, "Competitive Issues in the Deregulated United States Railroad Industry" (1997). Student Work. 1363. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/1363 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Competitive Issues in the Deregulated United States Railroad Industry A Thesis Presented to Business Administration and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Business Administration University of Nebraska at Omaha by Johannes Christian Koeppe November 1997 UMI Number: EP73403 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissartatton Publishing UMI EP73403 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 ii THESIS ACCEPTANCE Acceptance for hte faculty of the Graduate College, University of Nebraska, in partial fullfillment of the Requriements for the degree of Master of Business Administration, University of Nebraska at Omaha. -

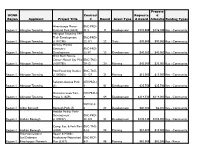

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste D Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type D Award Allocatio Funding Types

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Alverthorpe Manor BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Cultural Park (6422) 11-3 11 Development $223,000 $136,900 Key - Community Abington Township TAP Trail- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township (1101296) 22-171 22 Trails $90,000 $90,000 Key - Community Ardsley Wildlife Sanctuary- BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Development 22-37 22 Development $40,000 $40,000 Key - Community Briar Bush Nature Center Master Site Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1007785) 20-12 20 Planning $42,000 $37,000 Key - Community Pool Feasibility Studies BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1100063) 21-127 21 Planning $15,000 $15,000 Key - Community Rubicam Avenue Park KEY-PRD-1- Region 1 Abington Township (1) 1 01 Development $25,750 $25,700 Key - Community Demonstration Trail - KEY-PRD-4- Region 1 Abington Township Phase I (1659) 4 04 Development $114,330 $114,000 Key - Community KEY-SC-3- Region 1 Aldan Borough Borough Park (5) 6 03 Development $20,000 $2,000 Key - Community Ambler Pocket Park- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Ambler Borough (1102237) 23-176 23 Development $102,340 $102,000 Key - Community Comp. Rec. & Park Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Ambler Borough (4438) 8-16 08 Planning $10,400 $10,000 Key - Community American Littoral Upper & Middle Soc/Delaware Neshaminy Watershed BRC-RCP- Region 1 Riverkeeper Network Plan (3337) 6-9 06 Planning $62,500 $62,500 Key - Rivers Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Valley View Park - Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Aston Township (1100582) 21-114 21 Development $184,000 $164,000 Key - Community Comp. -

612-373-3933 Winter Construction Conditions Continue As Pa

Web: swlrt.org Twitter: @SouthwestLRT Construction Hotline: 612-373-3933 Winter Construction Conditions Continue As part of the normal flow of construction, some portions of the project corridor will remain quiet through the winter. However, active construction work continues in each city along the alignment, as crews focus on items that are critical to the overall project schedule or that can still easily be done in the winter. Please continue to expect crews and construction vehicles throughout the project route. Weekly Construction Photo: Beltline Boulevard Regional Trail Bridge in St. Louis Park Crews placed the bridge span for the Beltline Boulevard regional trail bridge over the freight rail tracks this past week. Watch a time-lapse video of crews setting the span. 1 | Page Eden Prairie Eden Prairie Construction: Map 1 of 2 SouthWest Station to Eden Prairie Town Center Station Construction Overview: At the SouthWest Station we are constructing a new park-and-ride ramp adjacent to the existing ramp and a combined bus and LRT station. Moving east, the Prairie Center Drive LRT Bridge extends from the SouthWest Station area over Technology Drive and Prairie Center Drive. Moving east, LRT will enter the Eden Prairie Town Center Station area. Current activities to expect in this area: • The right-turn lane on the eastbound Highway 212 ramp to Prairie Center Drive remains closed. • The SouthWest station area remains a busy construction site with ongoing piling and concrete work. 2 | Page • Concrete work and bridge walkway preparation will create roadway impacts on Prairie Center Drive during the week of February 1. -

Freight Rail B

FREIGHT RAIL B Pennsylvania has 57 freight railroads covering 5127 miles across the state, ranking it 4th largest rail network by mileage in the U.S. By 2035, 246 million tons of freight is expected to pass through the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, an increase of 22 percent over 2007 levels. Pennsylvania’s railroad freight demand continues to exceed current infrastructure. Railroad traffic is steadily returning to near- World War II levels, before highways were built to facilitate widespread movement of goods by truck. Rail projects that could be undertaken to address the Commonwealth’s infrastructure needs total more than $280 million. Annual state-of-good-repair track and bridge expenditures for all railroad classes within the Commonwealth are projected to be approximately $560 million. Class I railroads which are the largest railroad companies are poised to cover their own financial needs, while smaller railroads are not affluent enough and some need assistance to continue service to rural areas of the state. BACKGROUND A number of benefits result from using rail freight to move goods throughout the U.S. particularly on longer routes: congestion mitigation, air quality improvement, enhancement of transportation safety, reduction of truck traffic on highways, and economic development. Railroads also remain the safest and most cost efficient mode for transporting hazardous materials, coal, industrial raw materials, and large quantities of goods. Since the mid-1800s, rail transportation has been the centerpiece of industrial production and energy movement. Specifically, in light of the events of September 11, 2001 and from a national security point of view, railroads are one of the best ways to produce a more secure system for transportation of dangerous or hazardous products.