The University of Chicago Noun Categorization in Ojibwe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration for Teaching Colors in Menominee

The Complexity of Simple Things: Cross-disciplinary Collaboration for Teaching Colors in Menominee Monica Macaulay Linguistics Department Rita MacDonald School of Education 3/9/17 UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN 1 Who we are • Language documentation, • Applied linguistics, SLA description, analysis and TESOL • Language teacher & teacher educator Rita Monica Menominee Language and Culture Commission 3/9/17 UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN 2 3/9/17 UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN 3 Menominee Language • Algonquian language of Wisconsin • Documented 1921-1949 by Leonard Bloomfield • MM: working with community since 1998 3/9/17 UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN 4 Menominee Language Revitalization Current status: • Fewer than 5 L1 speakers, all elderly • Small number of proficient L2 speakers • No external communiMes of speakers • 2016-present: Tribal program to train teachers 1. to speak Menominee (14 months) 2. to become teachers for pre-school immersion 3/9/17 UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN 5 Menominee Language Revitalization Current status: • Fewer than 5 L1 speakers, all elderly • Small number of proficient L2 speakers • No external communiMes of speakers • 2016-present: Tribal efforts to train teachers 1. to speak Menominee (14 months) 2. to become teachers for pre-school immersion COLORS!! 3/9/17 UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN 6 Past Attempt: CL’s lesson § doctoral student in Included sentences like these Curriculum and Instruction for me to translate: § interested in intergenerational • What color do you see? transmission of language • I see orange. § no training in linguistics • What’s your favorite color? § some SLA training • My favorite color is blue. § had idea of lesson on colors as • Touch someone wearing red. sample lesson for teachers • Touch someone wearing a red shirt. -

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

An Analysis of Semantic and Syntactic Negation in Oshiwambo and English

JULACE: Journal of University of Namibia Language Centre Volume 4, No. 2, 2019 (ISSN 2026-8297) An analysis of semantic and syntactic negation in Oshiwambo and English Immanuel N. Shatepa1 Namibia University of Science and Technology Abstract Negation in languages has been documented since the 1970s and 1980s. This paper attempts to explain the negation structures in semantic and syntactic structures of Oshiwambo and English languages. These two languages have two complete negation structures and how they function to achieve negation is far from being similar. The focus of the paper was on the analysis of the sentential negation and how negative particles are used in English and Oshiwambo, a Bantu language. It analyzes and compares the use of full negatives, affixes and quasi negative words to achieve negation in English and Oshiwambo language. The Oshiwambo and English texts/contents were purposely sampled and content analysis was performed accordingly. The analysis shows that Bantu languages share a common rule of negation which is the use of a pre- initial prefix while the rules to changing negative imperative to interrogative or declarative are different between English and Oshiwambo. Keywords: pre-initial, negation, marker, imperative, declarative, integrative, syntactic, semantic, Bantu Introduction A number of studies on negation of English and Bantu languages have been conducted by linguists. Studies by Kim and Sag (1995); Neba and Tanda (2005) and Weir (2013) show that negation differs from language to language. They further state highlighted that since every language has its own morphological and semantic components to express negation, one rule fits all simply does not work. -

Language in the USA

This page intentionally left blank Language in the USA This textbook provides a comprehensive survey of current language issues in the USA. Through a series of specially commissioned chapters by lead- ing scholars, it explores the nature of language variation in the United States and its social, historical, and political significance. Part 1, “American English,” explores the history and distinctiveness of American English, as well as looking at regional and social varieties, African American Vernacular English, and the Dictionary of American Regional English. Part 2, “Other language varieties,” looks at Creole and Native American languages, Spanish, American Sign Language, Asian American varieties, multilingualism, linguistic diversity, and English acquisition. Part 3, “The sociolinguistic situation,” includes chapters on attitudes to language, ideology and prejudice, language and education, adolescent language, slang, Hip Hop Nation Language, the language of cyberspace, doctor–patient communication, language and identity in liter- ature, and how language relates to gender and sexuality. It also explores recent issues such as the Ebonics controversy, the Bilingual Education debate, and the English-Only movement. Clear, accessible, and broad in its coverage, Language in the USA will be welcomed by students across the disciplines of English, Linguistics, Communication Studies, American Studies and Popular Culture, as well as anyone interested more generally in language and related issues. edward finegan is Professor of Linguistics and Law at the Uni- versity of Southern California. He has published articles in a variety of journals, and his previous books include Attitudes toward English Usage (1980), Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Register (co-edited with Douglas Biber, 1994), and Language: Its Structure and Use, 4th edn. -

Classifiers: a Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Modern & Classical Languages Humanities 3-2002 Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J. Vajda Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Vajda, Edward J., "Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization" (2002). Modern & Classical Languages. 35. https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs/35 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern & Classical Languages by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J. Linguistics38 (2002), I37-172. ? 2002 CambridgeUniversity Press Printedin the United Kingdom REVIEWS J. Linguistics 38 (2002). DOI: Io.IOI7/So022226702211378 ? 2002 Cambridge University Press Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, Classifiers: a typology of noun categorization devices.Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2000. Pp. xxvi+ 535. Reviewedby EDWARDJ. VAJDA,Western Washington University This book offers a multifaceted,cross-linguistic survey of all types of grammaticaldevices used to categorizenouns. It representsan ambitious expansion beyond earlier studies dealing with individual aspects of this phenomenon, notably Corbett's (I99I) landmark monograph on noun classes(genders), Dixon's importantessay (I982) distinguishingnoun classes fromclassifiers, and Greenberg's(I972) seminalpaper on numeralclassifiers. Aikhenvald'sClassifiers exceeds them all in the number of languages it examines and in its breadth of typological inquiry. The full gamut of morphologicalpatterns used to classify nouns (or, more accurately,the referentsof nouns)is consideredholistically, with an eye towardcategorizing the categorizationdevices themselvesin terms of a comprehensiveframe- work. -

Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals As Windows Into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer

University of Massachusetts Amherst From the SelectedWorks of Angelika Kratzer 2009 Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer Available at: https://works.bepress.com/angelika_kratzer/ 6/ Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer This article argues that natural languages have two binding strategies that create two types of bound variable pronouns. Pronouns of the first type, which include local fake indexicals, reflexives, relative pronouns, and PRO, may be born with a ‘‘defective’’ feature set. They can ac- quire the features they are missing (if any) from verbal functional heads carrying standard -operators that bind them. Pronouns of the second type, which include long-distance fake indexicals, are born fully specified and receive their interpretations via context-shifting -operators (Cable 2005). Both binding strategies are freely available and not subject to syntactic constraints. Local anaphora emerges under the assumption that feature transmission and morphophonological spell-out are limited to small windows of operation, possibly the phases of Chomsky 2001. If pronouns can be born underspecified, we need an account of what the possible initial features of a pronoun can be and how it acquires the features it may be missing. The article develops such an account by deriving a space of possible paradigms for referen- tial and bound variable pronouns from the semantics of pronominal features. The result is a theory of pronouns that predicts the typology and individual characteristics of both referential and bound variable pronouns. Keywords: agreement, fake indexicals, local anaphora, long-distance anaphora, meaning of pronominal features, typology of pronouns 1 Fake Indexicals and Minimal Pronouns Referential and bound variable pronouns tend to look the same. -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

Semantic Types and Type-Shifting. Conjunction and Type Ambiguity

Partee and Borschev, Tarragona 3, April 15, 2005 Semantic Types and Type-shifting. Conjunction and Type Ambiguity. Noun Phrase Interpretation and Type-Shifting Principles. Barbara H. Partee, University of Massachusetts, Amherst Vladimir Borschev, VINITI, Russian Academy of Sciences, and Univ. of Massachusetts, Amherst [email protected], [email protected]; http://people.umass.edu/partee/ Universidad Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, April 15, 2005 1. Linguistic background:....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Categorial grammar and syntax-semantics correspondence: centrality of function-argument application . 1 1.2. Tensions among simplicity, generality, uniformity and flexiblity........................................................... 1 2. Conjunction and Type Ambiguity (from Partee & Rooth, 1983)....................................................................... 2 2.0. To be explained: cross-categorial distribution and meaning of ‘and’, ‘or’. .................................................2 2.1. Generalized conjunction.............................................................................................................................. 3 2.2. Repercussions on the type theory: against uniformity, for "simplicity" and type-shifting.......................... 3 2.3. Proposal:...................................................................................................................................................... -

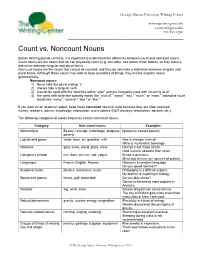

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Introduction to Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles: ALAOTSIKKO

1 Introduction to Case, animacy and semantic roles Please cite this paper as: Kittilä, Seppo, Katja Västi and Jussi Ylikoski. (2011) Introduction to case, animacy and semantic roles. In: Kittilä, Seppo, Katja Västi & Jussi Ylikoski (Eds.), Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles, 1-26. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Seppo Kittilä Katja Västi Jussi Ylikoski University of Helsinki University of Oulu University of Helsinki University of Helsinki 1. Introduction Case, animacy and semantic roles and different combinations thereof have been the topic of numerous studies in linguistics (see e.g. Næss 2003; Kittilä 2008; de Hoop & de Swart 2008 among numerous others). The current volume adds to this list. The focus of the chapters in this volume lies on the effects that animacy has on the use and interpretation of cases and semantic roles. Each of the three concepts discussed in this volume can also be seen as somewhat problematic and not always easy to define. First, as noted by Butt (2006: 1), we still have not reached a full consensus on what case is and how it differs, for example, from 2 the closely related concept of adpositions. Second, animacy, as the label is used in linguistics, does not fully correspond to a layperson’s concept of animacy, which is probably rather biology-based (see e.g. Yamamoto 1999 for a discussion of the concept of animacy). The label can therefore, if desired, be seen as a misnomer. Lastly, semantic roles can be considered one of the most notorious labels in linguistics, as has been recently discussed by Newmeyer (2010). There is still no full consensus on how the concept of semantic roles is best defined and what would be the correct or necessary number of semantic roles necessary for a full description of languages. -

Morphological Classes and Gender in Ɓəna-Yungur

Morphological classes and gender in əna-Yungur Mark van de Velde, Dmitry Idiatov To cite this version: Mark van de Velde, Dmitry Idiatov. Morphological classes and gender in əna-Yungur. Shigeki Kaji. Proceedings of the 8th World Congress of African Linguistics, Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, pp.53-65, 2017. halshs-01484016 HAL Id: halshs-01484016 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01484016 Submitted on 6 Mar 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Morphological classes and gender in Ɓə́ná-Yungur Mark Van de Velde1,2 & Dmitry Idiatov1,2 1Llacan (UMR 8135 CNRS – USPC/Inalco), Paris, France 2Research Centre for Nigerian Languages, KWASU, Malete, Nigeria Abstract This paper provides an analysis of the gender system of Ɓə́ná-Yungur (glottocode: bena1260), distinguishing noun classes proper, defined as agreement classes, from morphological classes, defined in terms of number marking on nouns. The gender system is typologically unusual in its symmetry and simplicity. Ɓə́ná-Yungur has three noun classes in the singular and the same three classes in the plural. All logically possible singular-plural pairings are attested, except one. -

The “Person” Category in the Zamuco Languages. a Diachronic Perspective

On rare typological features of the Zamucoan languages, in the framework of the Chaco linguistic area Pier Marco Bertinetto Luca Ciucci Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa The Zamucoan family Ayoreo ca. 4500 speakers Old Zamuco (a.k.a. Ancient Zamuco) spoken in the XVIII century, extinct Chamacoco (Ɨbɨtoso, Tomarâho) ca. 1800 speakers The Zamucoan family The first stable contact with Zamucoan populations took place in the early 18th century in the reduction of San Ignacio de Samuco. The Jesuit Ignace Chomé wrote a grammar of Old Zamuco (Arte de la lengua zamuca). The Chamacoco established friendly relationships by the end of the 19th century. The Ayoreos surrended rather late (towards the middle of the last century); there are still a few nomadic small bands in Northern Paraguay. The Zamucoan family Main typological features -Fusional structure -Word order features: - SVO - Genitive+Noun - Noun + Adjective Zamucoan typologically rare features Nominal tripartition Radical tenselessness Nominal aspect Affix order in Chamacoco 3 plural Gender + classifiers 1 person ø-marking in Ayoreo realis Traces of conjunct / disjunct system in Old Zamuco Greater plural and clusivity Para-hypotaxis Nominal tripartition Radical tenselessness Nominal aspect Affix order in Chamacoco 3 plural Gender + classifiers 1 person ø-marking in Ayoreo realis Traces of conjunct / disjunct system in Old Zamuco Greater plural and clusivity Para-hypotaxis Nominal tripartition All Zamucoan languages present a morphological tripartition in their nominals. The base-form (BF) is typically used for predication. The singular-BF is (Ayoreo & Old Zamuco) or used to be (Cham.) the basis for any morphological operation. The full-form (FF) occurs in argumental position.