Antigonus Ii Gonatas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johnny Okane (Order #7165245) Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition

johnny okane (order #7165245) Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition Weloe to the Hurlat Pulishig editio of Miro Warfare “eries: Miro Ancients This series of games was original published by Tabletop Games in the 1970s with this title being published in 1976. Each game in the series aims to recreate the feel of tabletop wargaming with large numbers of miniatures but using printed counters and terrain so that games can be played in a small space and are very cost-effective. In these new editions we have kept the rules and most of the illustrations unchanged but have modernised the layout and counter designs to refresh the game. These basic rules can be further enhanced through the use of the expansion sets below, which each add new sets of army counters and rules to the core game: Product Subject Additional Armies Expansion I Chariot Era & Far East Assyrian; Chinese; Egyptian Expansion II Classical Era Indian; Macedonian; Persian; Selucid Expansion III Enemies of Rome Britons; Gallic; Goth Expansion IV Fall of Rome Byzantine; Hun; Late Roman; Sassanid Expansion V The Dark Ages Norman; Saxon; Viking Happy gaming! Kris & Dave Hurlbat July 2012 © Copyright 2012 Hurlbat Publishing Edited by Kris Whitmore Contents Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition ................................................................................................................................... 2 Move Procedures ............................................................................................................................................................................... -

The Coins from the Necropolis "Metlata" Near the Village of Rupite

margarita ANDONOVA the coins from the necropolis "metlata" near the village of rupite... THE COINS FROM THE NECROPOLIS METLATA NEAR THE VILLAGE "OF RUPITE" (F. MULETAROVO), MUNICIPALITY OF PETRICH by Margarita ANDONOVA, Regional Museum of History– Blagoevgrad This article sets to describe and introduce known as Charon's fee was registered through the in scholarly debate the numismatic data findspots of the coins on the skeleton; specifically, generated during the 1985-1988 archaeological these coins were found near the head, the pelvis, excavations at one of the necropoleis situated in the left arm and the legs. In cremations in situ, the locality "Metlata" near the village of Rupite. coins were placed either inside the grave or in The necropolis belongs to the long-known urns made of stone or clay, as well as in bowls "urban settlement" situated on the southern placed next to them. It is noteworthy that out of slopes of Kozhuh hill, at the confluence of 167 graves, coins were registered only in 52, thus the Strumeshnitsa and Struma Rivers, and accounting for less than 50%. The absence of now identified with Heraclea Sintica. The coins in some graves can probably be attributed archaeological excavations were conducted by to the fact that "in Greek society, there was no Yulia Bozhinova from the Regional Museum of established dogma about the way in which the History, Blagoevgrad. souls of the dead travelled to the realm of Hades" The graves number 167 and are located (Зубарь 1982, 108). According to written sources, within an area of 750 m². Coins were found mainly Euripides, it is clear that the deceased in 52 graves, both Hellenistic and Roman, may be accompanied to the underworld not only and 10 coins originate from areas (squares) by Charon, but also by Hermes or Thanatos. -

The Antigonids and the Ruler Cult. Global and Local Perspectives?

The Antigonids and the Ruler Cult Global and Local Perspectives? 1 Franca Landucci DOI – 10.7358/erga-2016-002-land AbsTRACT – Demetrius Poliorketes is considered by modern scholars the true founder of ruler cult. In particular the Athenians attributed him several divine honors between 307 and 290 BC. The ancient authors in general consider these honors in a negative perspec- tive, while offering words of appreciation about an ideal sovereignty intended as a glorious form of servitude and embodied in Antigonus Gonatas, Demetrius Poliorketes’ son and heir. An analysis of the epigraphic evidences referring to this king leads to the conclusion that Antigonus Gonatas did not officially encourage the worship towards himself. KEYWORDS – Antigonids, Antigonus Gonatas, Demetrius Poliorketes, Hellenism, ruler cult. Antigonidi, Antigono Gonata, culto del sovrano, Demetrio Poliorcete, ellenismo. Modern scholars consider Demetrius Poliorketes the true founder of ruler cult due to the impressively vast literary tradition on the divine honours bestowed upon this historical figure, especially by Athens, between the late fourth and the early third century BC 2. As evidenced also in modern bib- liography, these honours seem to climax in the celebration of Poliorketes as deus praesens in the well-known ithyphallus dedicated to him by the Athenians around 290 3. Documentation is however pervaded by a tone that is strongly hostile to the granting of such honours. Furthermore, despite the fact that it has been handed down to us through Roman Imperial writers like Diodorus, Plutarch and Athenaeus, the tradition reflects a tendency contemporary to the age of the Diadochi, since these same authors refer, often explicitly, to a 1 All dates are BC, unless otherwise stated. -

Alexander's Successors

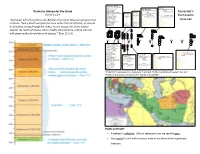

Perdiccas, 323-320 Antigonus (western Asia Minor) 288-285 Antipater (Macedonia) 301, after Ipsus Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Archon (Babylon) Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Ptolemy (Egypt) Asander (Caria) Ptolemy (Egypt) Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Persia to Alexander the Great Atropates (northern Media) 315-311 Alexander’s Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Eumenes (Cappadocia, Pontus) vs. 318-316 Cassander Cassander (Macedonia) Laomedon (Syria) Lysimachus Daniel 11:1-4 Antigonus Demetrius (Cyprus, Tyre, Demetrius (Macedonia, Cyprus, Leonnatus (Phrygia) Ptolemy Successors Cassander Sidon, Agaean islands) Tyre, Sidon, Agaean islands) Lysimachus (Thrace) Peithon Seleucus Menander (Lydia) Ptolemy Bythinia Bythinia Olympias (Epirus) vs. 332-260 BC Seleucus Epirus Epirus “And now I will tell you the truth. Behold, three more kings are going to arise Peithon (southern Media) Antigonus Greece Greece Philippus (Bactria) vs. Aristodemus Heraclean kingdom Heraclean kingdom Ptolemy (Egypt) Demetrius in Persia. Then a fourth will gain far more riches than all of them; as soon as Eumenes Paeonia Paeonia Stasanor (Aria) Nearchus Olympias Pontus Pontus and others . Peithon Polyperchon Rhodes Rhodes he becomes strong through his riches, he will arouse the whole empire against the realm of Greece. And a mighty king will arise, and he will rule with great authority and do as he pleases.” (Dan 11:2-3) 320 330310 300 290 280 270 260 250 Antipater, 320-319 Alcetas and Attalus (Pisidia ) Antigenes (Susiana) Antigonus (army in Asia) Arrhidaeus (Phrygia) Cassander -

9780521812085 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 0521812089 - Polybius, Rome and the Hellenistic World: Essays and Reflections Frank W. Walbank Index More information Indexes I GENERAL Dionysus and Heracles, ; war against Persiaplannedby Philip II, Abydus, Philip V takes, – Alexander, governor of Corinth, declares Acarnania, Philip V campaigns in, independence, Achaea, Achaean League: possible Alexandria, temple of Demeter and Kore and development out of village communities, Thesmophorion at, – ; Adonis festival, ; rise of poleis in, ; cities not attested ; nature of population, –; Polybius’ archaeologically before , ; Spartans picture impressionistic, introduce oligarchies, ; garrisons and Ambracia, Philip V campaigns in, tyrants under Antigonus II, ; coinage, Ambracus, ; Calydon belongs to, ; revival in Ameinias, Phocian pirate, third century, –, , ; appeals to Andriscus, Macedonian pretender, ; Doson, ; Achaeans detained at support for him a sign of infatuation, Rome, ; Achaean assemblies, –; Andros, battle of, , ; date of, possesses primary assembly down to , Antander, historian, ; dominated byelite, ´ ; Achaean Antigonids, and sea-power, – ; allegedly War, – aimed at universal dominion, , –; Achaeus, provides example to Polybius’ failed to maintain naval preponderance, readers, ; claimed connection with Argeads, Actium, battle of, Acusilaus of Argos, Antigonus I Monophthalmus, faces Ptolemy, Admetus, Macedonian, honoured at Delos, Cassander and Lysimachus, ; death at Ipsus, Aegeira, Antigonus II Gonatas, need for fleet, -

STRATEGIES of UNITY WITHIN the ACHAEAN LEAGUE By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Utah: J. Willard Marriott Digital Library STRATEGIES OF UNITY WITHIN THE ACHAEAN LEAGUE by Andrew James Hillen A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History The University of Utah December 2012 Copyright © Andrew James Hillen 2012 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Andrew James Hillen has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: W. Lindsay Adams , Chair June 26, 2012 Date Approved Ronald Smelser , Member June 26, 2012 Date Approved Alexis Christensen , Member June 26, 2012 Date Approved and by Isabel Moreira , Chair of the Department of History and by Charles A. Wight, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT The Achaean League successfully extended its membership to poleis who did not traditionally share any affinity with the Achaean ethnos. This occurred, against the current of traditional Greek political development, due to a fundamental restructuring of political power within the poleis of the Peloponnesus. Due to Hellenistic, and particularly Macedonian intervention, most Peloponnesian poleis were directed by tyrants who could make decisions based on their sole judgments. The Achaean League positioned itself to directly influence those tyrants. The League offered to maintain the tyrants within their poleis so long as they joined the League, or these tyrants faced relentless Achaean attacks and assassination attempts. Through the consent of this small tyrannical elite, the Achaean League grew to encompass most of the Peloponnesus. -

December 3, 1992 CHAPTER VIII

December 3, 1992 CHAPTER VIII: EARLY HELLENISTIC DYNAMISM, 323-146 Aye me, the pain and the grief of it! I have been sick of Love's quartan now a month and more. He's not so fair, I own, but all the ground his pretty foot covers is grace, and the smile of his face is very sweetness. 'Tis true the ague takes me now but day on day off, but soon there'll be no respite, no not for a wink of sleep. When we met yesterday he gave me a sidelong glance, afeared to look me in the face, and blushed crimson; at that, Love gripped my reins still the more, till I gat me wounded and heartsore home, there to arraign my soul at bar and hold with myself this parlance: "What wast after, doing so? whither away this fond folly? know'st thou not there's three gray hairs on thy brow? Be wise in time . (Theocritus, Idylls, XXX). Writers about pederasty, like writers about other aspects of ancient Greek culture, have tended to downplay the Hellenistic period as inferior. John Addington Symonds, adhering to the view of the great English historian of ancient Greece, George Grote, that the Hellenistic Age was decadent, ended his Problem in Greek Ethics with the loss of Greek freedom at Chaeronea: Philip of Macedon, when he pronounced the panegyric of the Sacred Band at Chaeronea, uttered the funeral oration of Greek love in its nobler forms. With the decay of military spirit and the loss of freedom, there was no sphere left for that type of comradeship which I attempted to describe in Section IV. -

Stratēgoi and the Administration of Greece Under the Antigonids

STRATĒGOI AND THE ADMINISTRATION OF GREECE UNDER THE ANTIGONIDS Alexander Michael Seufert A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History (Ancient). Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Fred Naiden Richard Talbert Joshua Sosin ©2012 Alexander Michael Seufert ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ALEXANDER MICHAEL SEUFERT: Stratēgoi and the Administration of Greece under the Antigonids. (Under the direction of Fred Naiden) This thesis investigates the policies of the Antigonid Dynasty towards the poleis of its kingdom by examining the highest military office of the kingdom, the stratēgos. This work takes special care to mark the civic responsibilities of the office from the time of Antigonus Gonatas to the eventual conquest by Rome in order to elucidate the manner in which the Macedonians oversaw the difficult task of establishing and maintaining control over their subject cities. The thesis aims to show that the Antigonid kings sought to create a delicate balance between their own interests and the interests of the populace. In doing so, they were keen to take traditional sensibilities into account when governing over the poleis. Contrary to previous scholarship, this thesis shows that the Antigonids allowed local elections of military positions to take place, and did not suppress existing magistracies within subject cities. iii Table of Contents Abbreviations .............................................................................................................................v -

The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2Nd Edition Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Frontmatter More Information The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest The Hellenistic period (323–30 bc) began with the considerable expansion of the Greek world through the Macedonian conquest of the Persian empire and ended with Rome becoming the predominant political force in that world. This new and enlarged edition of Michel Austin’s seminal work provides a panoramic view of this world through the medium of ancient sources. It now comprises over three hundred texts from literary, epigraphic and papyrological sources which are presented in original translations and supported by introductory sections, detailed notes and references, chronological tables, maps, illustrations of coins, and a full analytical index. The first edition has won widespread admiration since its publication in 1981. Updated and expanded with reference to the most recent scholarship on the subject, this new edition will prove invaluable for the study of a period which has received increasing recognition. michel austin is Honorary Senior Lecturer in Ancient History at the University of St Andrews. His previous publications include Economic and Social History of Ancient Greece. An Introduction (1977). He is the author of numerous articles and was a contributor to the Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VI (2nd edition, 1994). © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Frontmatter More Information The Hellenistic World From Alexander to the Roman Conquest A selection of ancient sources in translation Second augmented edition M. -

Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age

Macquarie University Department of Ancient History 2nd Semester, 2011. AHIS 241 / 341 AlexanderAlexander thethe GreatGreat andand thethe HellenisticHellenistic AgeAge Unit Outline, Schedule, Tutorial Materials and Bibliography 1 Contents: Unit Introduction and Requirements p. 3 Unit Schedule: Lecture and Tutorial topics p. 9 Map 1: Alexander's March of Conquest. p. 11 Weekly Tutorial Materials p. 12 Map 2: Alexander's Successors, 303 B.C. p. 17 Map 3: The 3rd Century World of Alexander’s Successors p. 18 Map 4: The Background to the Maccabean Revolt p. 27 Unit Main Bibliography p. 32 2 Macquarie University Department of Ancient History 2011 AHIS 241 / 341: Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age. UNIT INTRODUCTION This Unit on Alexander the Great and the ‘Hellenistic Age’ will begin with the political situation in Fourth Century Greece and the rise of Macedon. It will focus first on the career of Alexander the Great, and the interpretation of a number of key episodes in his life. The aim will be to build up an overall picture of his motives and achievements, and the consequences of his extraordinary conquests for later history. The focus will then turn to the break up of his ‘Empire’ at his death, and the warfare among his successors which led to the creation of the great rival kingdoms of the Hellenistic period. The Unit will be primarily a study in cultural history, set against the background of the political history of the Mediterranean world. It will not be tied to an event-by-event account of the post- Classical Greek world, but will focus also on the history of ideas and institutions. -

POLITICS of the PTOLEMAIC DYNASTY Monica Omoye Aneni

POLITICS OF THE PTOLEMAIC DYNASTY Monica Omoye Aneni* http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/og.v12i 1.7 Abstract Hellenistic studies and Egyptology have concentrated on the spread and influence of Hellenism, on the one hand, and the value of ancient Egypt’s monument and artifacts, on the other hand. This study focuses on the politics that directed and helped sustain the successors of Alexander the Great on the throne of Egypt. Ptolemy 1 Soter, the instigator of the Ptolemaic dynasty, fought vehemently, gallantly and decisively to consolidate his authority and control over Egypt and her consequent spread. However, his successors played several politics; majorly that of assassination, for the enviable position of Pharaoh, unfortunately, to the detriment of the state. This study contends that besides the earliest Ptolemies, the other successors, having ignored the legacy of Ptolemy 1 Soter and the expansion of Egypt’s frontiers, fostered and nurtured this politics of assassination among others. It concludes with the argument that the contenders encouraged political retrogression to the nadir and therefore were not fit for the throne, for this politics of assassination among others reduced Egypt and hindered her from attaining the status of a much more formidable world power that would have been reckoned with during that period. The study is historical in nature but adopts the expository method. Studies that may interpret Egypt’s strong diplomatic relations with other ancient nations are recommended. Keywords: Politics, Egypt, Ptolemaic dynasty, successors, assassination Introduction Several ancient authors present expository narratives about different political, economic, social and religious activities of the Omoye Aneni: Politics of the Ptolemaic dynasty various eras that characterize ancient times. -

Alexander the Great (17)

Alexander the Great (17) Alexander the Great (*356; r. 336-323): the Macedonian king who defeated his Persian colleague Darius III Codomannus and conquered the Achaemenid Empire. During his campaigns, Alexander visited a.o. Egypt, Babylonia, Persis, Media, Bactria, the Punjab, and the valley of the Indus. In the second half of his reign, he had to find a way to rule his newly conquered countries. Therefore, he made Babylon his capital and introduced the oriental court ceremonial, which caused great tensions with his Macedonian and Greek officers. This is the seventeenth of a series of articles. A complete overview can be found here and a chronological table of his reign can be found here. The purple testament of bleeding war The settlement of Babylon Alexander died in the afternoon of 11 June 323 BCE. Next day, his generals met to discuss the new situation. Under normal circumstances, they, as representatives of the Macedonian nation in arms, were to choose a new king. This could be easy, because the dead king had a brother, Arridaeus. However, he was considered mentally unfit to rule. As a consequence, it was difficult to reach a solution. According to Quintus Curtius Rufus, Perdiccas, the commander of the Companion cavalry who had been appointed by Alexander as his successor, said that it was best to wait until Roxane, who was pregnant, had given birth. If it were a son, it would be logical to chose him as the new king. This was all too transparent: Perdiccas wanted to be in sole command until the boy had grown up.