Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sveučilište U Zagrebu Filozofski Fakultet Odsjek

SVEU ČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA POVIJEST UMJETNOSTI Diplomski rad VIZUALNI IDENTITET SUVREMENE HRVATSKE GLAZBENE ROCK I POP PRODUKCIJE (1990.-2010.) Mateja Pavlic Mentor: dr.sc. Frano Dulibi ć Zagreb, 2014. Temeljna dokumentacijska kartica Sveu čilište u Zagrebu Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za povijest umjetnosti Diplomski studij Diplomski rad VIZUALNI IDENTITET SUVREMENE HRVATSKE GLAZBENE ROCK I POP PRODUKCIJE (1990.-2010.) Mateja Pavlic Rad se bavi vizualnim identitetom suvremene hrvatske glazbene rock i pop produkcije od 1990. do 2010. godine. Prikazana je povijesni razvoj prakse formiranja omota albuma plo ča/CD-a kao vizualne prezentacije glazbenih djela, što rezultira vrijednim likovnim ostvarenjima. Predmet zanimanja je usmjeren na rock pop omote albuma, koji proizlaze iz supkulturnog miljea te se za njih veže odre đena estetika i ikonografija. Pokušalo se naglasiti vrijednost omota, kao umjetni čkih djela, čija vrijednost nadilazi omote marketinških proizvoda, čemu u prilog ide i uklju čivanje etabliranih umjetnika u dizajn omota. Drugi dio rada bavi se konkretno situacijom u Hrvatskoj od 1990. do 2010. godine, odnosno kako su odre đeni čimbenici, s jedne strane jugoslavensko naslje đe oblikovanja omota, raspad Jugoslavije, ratna i poslijeratna situacija, nova društveno-politi čka klima, potiskivanje rock žanra na marginu, s druge strane promjene na tehnološkoj razini, zamjena plo ča s CD-ovima, odnosno digitalizacija glazbe te razvoj profesionalne dizajnerske djelatnosti, utjecali na oblikovanje omota rock pop albuma glazbenika koji prevladavaju na glazbenim ljestvicama i dodjelama nagrada. U radu su navedeni najdominantniji predstavnici rock pop glazbe i njihova poetika, dizajneri albuma te pojedina čni omoti. Prezentirani su i primjeri valorizacije rock pop albuma kao umjetni čke prakse na podru čju Hrvatske. -

Sweet September

MARK YOUR MAPS WITH THE BEST OF MARKETS * Agram German exonym its Austrian by outside Croatia known commonly more was Zagreb LIMITED EDITION INSTAGRAM* FREE COPY Zagreb in full color No. 06 SEPTEMBER ast month, Zagreb was abruptly left without Dolac. 2015. LFor one week, stalls and vendors migrated to Ban Jelačić Square, only to move back to their original place, but now repaved, refurbished and in full color again. The Z ‘misplaced’ Dolac was a unique opportunity to be remind- on Facebook ed of what things were like half a century ago. This month 64-second kiss there is another time-travel experience on Jelačić Square: on the world’s Vintage Festival in the Johann Franck cafe, taking us shortest funic- back to the 50s and 60s. Read more about it in this issue... ular ride The world’s shortest funicular was steam-powered Talkabout until 1934. The lower stop on Croatia Tomićeva Street GRIČ-BIT IS BACK! connects with the upper stop on The fifth edition of the the Strossmayer best street festival kicks promenade, off on the first day of in front of the ANJA MUTIĆ fall, joining forces with Lotršćak Tower. Author of Lonely Planet Croatia, writes for New the ‘At the Upper Town’ As the Zagreb York Magazine and The Washington Post. Follow her at @everthenomad initiative and showcas- oldest means of public transport, ing Device_art work- the funicular shops and exhibitions began operating Sweet hosted by Space Festival only a year and the Klovićevi Dvori before the horse- gallery. All this topped drawn tram. -

BIOGRAFIJA : HLADNO PIVO Ili Skraćeno HP, Na Sceni Se Pojavilo Krajem Osamdesetih ,Da Bi Već Devedesetih Postao Najpopularniji Hrvatski Punk Rock Sastav

HLADNO PIVO - Zagreb povodom 30 godina javnog umjetničkog glazbenog djelovanja BIOGRAFIJA : HLADNO PIVO ili skraćeno HP, na sceni se pojavilo krajem osamdesetih ,da bi već devedesetih postao najpopularniji hrvatski punk rock sastav. 1987.g. u zagrebačkom predgrađu Gajnice bend su osnovali Zoran Subošić – Zoki (gitara), Milan Kekin – Mile (vokal), Tadija Martinović – Teddy (bas gitara), Mladen Subošić – Suba (bubnjevi). U početku je u bendu bio i Stipe Anić (gitara).Prvi, legendarni koncert održali su 21.05.1988. g. u sklopu izviđačkog natjecanja u malom zagorskom mjestu Kumrovec. Odlaskom iz benda S. Anića (1989.), preostala četvorka snima prvi demo-album sa šest pjesama.Povratkom članova benda iz vojske 1990. g. bend nastavlja s radom, što rezultira pjesmama Princeza, Heroin, Dobro veče, Trening za umiranje, Buba švabe, Zakaj se tak’ oblačiš, Pjevajte nešto ljubavno. Suradnja između benda i Denisa (Denyken) urodila je plodom: 1991.g. pjesme izlaze na prvom izdanju kazete „Hladno pivo“ . Uslijedili su koncerti,a nakon jednog u KSET-u 1992. prihvaćaju ponudu i snimaju video-spota za pjesmu „ Buba švabe“,koji je nakon prikazivanja na „Hit-depou“ 1992. g. bandu omogućio širi medijski proboj. Prvi, legendarni album „Džinovski“ snimaju 1993.g.,(album je dobio PORINA).Zaredali su koncerti po Hrvatskoj i Sloveniji na kojima je Hladno Pivo izvrsno prihvaćeno. G.1994. -u maloj dvorani Doma sportova, 11. listopada 1994. Hladno Pivo je predgrupa legendarnoj američkoj grupi Ramones.“ Imali su tremu i odsvirali su vjerojatno svoj najbrži koncert ikada, ali vrijedilo je“. Godine koje slijede donose nove nastupe,turneje i albume (G.A.D.,“Desetka“),ali i novog basistu (Šoki).Četvrti studijski album „Pobjeda“ izlazi 1999.g.,a bendu kao pridruženi članovi pristupaju Stipe Mađor (truba) i Milko Kiš (Deda).Live album „ Istočno od Gajnica“ , snimljen je 2000.g. -

Popular Music and Narratives of Identity in Croatia Since 1991

Popular music and narratives of identity in Croatia since 1991 Catherine Baker UCL I, Catherine Baker, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated / the thesis. UMI Number: U592565 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592565 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 Abstract This thesis employs historical, literary and anthropological methods to show how narratives of identity have been expressed in Croatia since 1991 (when Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia) through popular music and through talking about popular music. Since the beginning of the war in Croatia (1991-95) when the state media stimulated the production of popular music conveying appropriate narratives of national identity, Croatian popular music has been a site for the articulation of explicit national narratives of identity. The practice has continued into the present day, reflecting political and social change in Croatia (e.g. the growth of the war veterans lobby and protests against the Hague Tribunal). -

Povijest-Rock-Scene

PETAR HAJEK POVIJEST NAŠIČKE ROCK SCENE ZAVIČAJNI MUZEJ NAŠICE, 2017. IZDAVAČ Zavičajni muzej Našice ZA IZDAVAČA Silvija Lučevnjak AUTOR I GLAVNI UREDNIK Petar Hajek KOAUTORI Aleksandar Holiga, Andrea Kopri Lončarić, Bojan Holiga, Boris Seničanin, Branka Hajek, Damir Šimunović, Daniel Kopri, Darko Silađi, Darko Dudjak, Davorin Silađi, Dean Kopri, Dražen Udovčić, Goran Stanić, Hrvoje Horvatek, Ivan Gelenčir, Ivica Pintarić, Ivan Sušjenka, Ivan Šimunić, Krešimir Stojanović, Marko Falamić, Marko Galetić, Marko Hrčka, Matija Matišić, Mihael Katavić, Naco Oster, Neven Škoro, Petar Hajek, Siniša Lolić, Tena Byemkovski, Tihomir Oreški, Vanja Hrvoje Dražić, Vinko Kubica, Zoran Gvozdanović, Zvonimir Hajek, Zvonko Hvizdak, Zvonko Koprivčić, Željko Schwabe LEKTORICA Silvija Šokić PRIJEVOD SAŽETKA NA ENGLESKI JEZIK Tin Jurković DIZAJN NASLOVNICE Ivan Lončarević GRAFIČKO OBLIKOVANJE Zvonko Pinter TISAK Tisak Našice d.o.o. za grafičku djelatnost i ostale usluge Našice, Ivane Brlić Mažuranić 1 A Tel. 031/ 655-202 Naklada 100 kom. ISBN 978-953-7606-23-7 CIP zapis dostupan je u računalnom katalogu Gradske i sveučilišne knjižnice Osijek pod brojem 140617099 3 RIJEČ IZDAVAČA Veliki muzeološki projekt u suradnji Zavičajnog muzeja Našice, Udruge mladih “Kreativni laboratorium” Našice i Turističke zajednice Grada Našica kulminirao je u Noći muzeja 2016. godine. Njegov je uspjeh pota- knuo Zavičajni muzej Našice na tiskanje nešto izmijenjenog kataloga izlož- be “Povijest našičke rock scene”. Svi koji su imali prilike biti tog siječanjskog dana (29. 1. 2016.) u prostorima našega muzeja, a kasnije i hotela, bili su vraćeni u prošlost našega zavičaja, čija je kulturna scena od 1960-ih godina obilježena i brojnim rock grupama. Na izložbi je muzej imao niz suradnika, od glavnoga autora Petra Hajeka, koji je uz Mariju Božić izvršio i odabir izložaka do brojnih osoba koje su posudile svoje predmete. -

Medkulturni Vodnik: Spletni Poslovni Priročnik Za Srečanja S Tujimi Ljudmi in Navadami

Medkulturni priročnik Medkulturni vodnik: spletni poslovni priročnik za srečanja s tujimi ljudmi in navadami Poslovni priročnik za srečanja s tujimi ljudmi in navadami, ki smo ga naslovili Managerski medkulturni vodnik, je nastal v sodelovanju s študenti in študentkami etnologije in kulturne antopologije. In kako so se pravzaprav ti avtorji znašli v navezi s poslovnim svetom, ki ga predstavlja Združenje Manager? Mar niso to poznavalci starodavnih običajev in raziskovalci malo poznanih ljudstev, na primer v brazilskem pragozdu ali na pacifiških otokih? Drži, ukvarjajo se tudi s tem in še z marsičim drugim. Vse bolj jih zanima tudi kultura »sodobnih plemen«, ki jih namesto v pragozdu ali na oddaljenih otočjih najdejo kar v podjetjih. Zanima jih, kako živijo managerji in kakšni so obredi v poslovnem svetu, poleg tega pa vse več delajo kot posredniki med poslovnimi kulturami - tako znotraj ene države kot tudi med podjetji iz različnih držav. S takšnim medkulturnim posredništvom v mislih smo pripravljali tudi vodnik, ki je pred vami. Če boste z njegovo pomočjo stkali vsaj eno novo vez s tujino, bo njegov namen dosežen. Če se boste ob branju zabavali, še toliko bolje! Pojasnilo Medkulturni vodnik je prostovoljni projekt, ki temelji na delu študentk in študentov med leti. Vodnik je namenjen lajšanju navezovanja poslovnih stikov med državami in vzpostavljanju dialoga med kulturami, poleg tega pa z njim predstavljamo možnosti za vključevanje študentov in študentk v poslovni svet ter povezovanje etnologije in kulturne antropologije ter gospodarstva. -

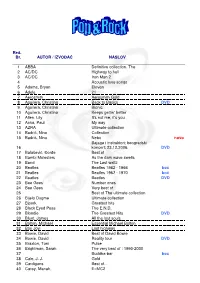

Red. Br. AUTOR / IZVOĐAČ NASLOV 1 ABBA Definitive Collection. the 2

Red. Br. AUTOR / IZVO ĐAČ NASLOV 1 ABBA Definitive collection. The 2 AC/DC Highway to hell 3 AC/DC Iron Man 2 4 Acoustic love songs 5 Adams, Bryan Eleven 6 Adele 21 7 Aerosmith Aerosmith Gold 8 Aguilera, Christina Back to Basics DVD 9 Aguilera, Christina Bionic 10 Aguilera, Christina Keeps gettin' better 11 Allen, Lily It's not me, it's you 12 Anka, Paul My way 13 AZRA Ultimate collection 14 Badri ć, Nina Collection 15 Badri ć, Nina Nebo novo Bajaga i instruktori; beogradski 16 koncert; 23.12.2006. DVD 17 Balaševi ć, Đor đe Best of 18 Bambi Molesters As the dark wave swells 19 Band The Last waltz 20 Beatles Beatles 1962 - 1966 box 21 Beatles Beatles 1967 - 1970 box 22 Beatles Beatles DVD 23 Bee Gees Number ones 24 Bee Gees Very best of 25 Best of The ultimate collection 26 Bijelo Dugme Ultimate collection 27 Bjoerk Greatest hits 28 Black Eyed Peas The E.N.D. 29 Blondie The Greatest Hits DVD 30 Blunt, James All the lost souls 31 Bolton, Michael Essential Michael Bolton 32 Bon Jovi Lost highway 33 Bowie, David Best of David Bowie 34 Bowie, David Reality tour DVD 35 Braxton, Toni Pulse 36 Brightman, Sarah The very best of : 1990-2000 37 Buddha-bar box 38 Cale, J. J. Gold 39 Cardigans Best of... 40 Carey, Mariah, E=MC2 41 Cetinski, Toni Ako to se zove ljubav 42 Cetinski, Toni Arena live 2008 DVD 43 Cetinski, Toni Triptonyc 44 Cetinski, Toni The Best of 2CD 45 Cher Gold 46 Cinquetti, Gigliola Chiamalo amore.. -

Hladnog Piva

Kinizam, cinizam, punk otpor: analiza albuma "Šamar" Hladnog piva Tuđan, Tea Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2015 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Rijeci, Filozofski fakultet u Rijeci Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:186:289900 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-30 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of the University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences - FHSSRI Repository SVEUČILIŠTE U RIJECI FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET U RIJECI ODSJEK ZA KULTURALNE STUDIJE Mentor: dr.sc. Vjeran Pavlaković Akademska godina: 2014./2015. KINIZAM, CINIZAM, PUNK ROCK OTPOR: ANALIZA ALBUMA „ŠAMAR“ HLADNOG PIVA (Završni rad) Studentica: Tea Tuđan Studij: Sveučilišni preddiplomski jednopredmetni studij kulturologije Rijeka, rujan 2015. SADRŽAJ: 1. SAŽETAK………………………………………………………………………..……3 2. UVOD………………………………………………………………………………….4 3. KINIZAM I CINIZAM………………………………………………………………...5 4. PUNK…………………………………………………………………………………..7 5. PUNK I KINIZAM…………………………………………………………………….8 6. HLADNO PIVO…………………………………………………………………...…10 7. POLITIČKO STANJE U HRVATSKOJ NA POČETKU 21.STOLJEĆA…………..12 8. ANALIZA ALBUMA „ŠAMAR“…………………………………………………...14 8.1. Čekaonica………………………………………………………………………...14 8.2. Cirkus…………………………………………………………………………….16 8.3. Šamar………………………………………………………………………….…18 8.4. Ljetni hit………………………………………………………………………….20 9. ZAKLJUČAK…………………………………………………………………….......24 10. LITERATURA………………………………………………………………………..25 -

Bosnians in Sweden – Music and Identity

RepoRts fRom the CentRe foR swedish folk musiC and Jazz Research 52 folk life studies fRom the Royal Gustavus adolphus Academy 19 Jasmina Talam Bosnians in Sweden – Music and Identity Svenskt visarkiv/Musikverket Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien Stockholm & Uppsala 2019 1 Svenskt visarkiv/Musikverket Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien © 2019 Statens musikverk & Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien and the author Layout and cover: Sofia Berry Cover photo: The archive of the Bosnian women’s association in Sweden Print: Stibo Complete ISBN 978-91-88957-25-2 ISSN 0071-6766 2 Preface In 2018, associate professor Jasmina Talam was awarded a scholarship from the Royal Gustavus Adolphus Academy for Swedish Folk Culture. Her scholarship was a part of the Bernadotte-program, which was founded in 2016 as a gift to His Majesty the King Carl XVI Gustaf on his 70th birthday. The program is a collaboration between five royal academies in Sweden. The Royal Gustav Adolphus Academy rewards non-Nordic scholars who want to spend at least half a year in Sweden, doing research at a university department or a scholarly archive or library. Ethnomusicologist Jasmina Talam normally works at the Academy of Music, University of Sarajevo. During her stay in Sweden, Svenskt visarkiv (The Swedish Centre for Folk Music and Jazz Research) functioned as host institution and the director of the archive, pro- fessor Dan Lundberg acted as her mentor. However, most of the time she was travelling around the country, energetically doing field work among the many Bosnian-Swedes. The focus of her project was the Bosnian associations and their organized music-making. -

Dve Decenije Exit Festivala 2

Uslovi za ulazak na EXIT festival bednija mesta masovnog okuplja- nja u zemlji. Protokol je zasnovan ECE EKREN Prema protokolu koji su sastavili Ujedinjeni festivali na najnovijim evropskim naučnim Srbije, ulazak će biti kontrolisan i ograničen na one istraživanjima, koja pokazuju da koji su vakcinisani, ili imaju dokaz da su preležali je, uz kontrolisan ulazak posetila- kovid-19, ili imaju negativan brzi, odnosno PCR test. ca, rizik od zaraze zanemarljiv. Pod ovakvim uslovima, srpski festivali su dobili sa- Tako se ulazak na EXIT ove godi- ne ograničava na one koji su vak- glasnost za održavanje od Kriznog štaba. Više deta- cinisani, ili imaju antitela nakon lja o načinu ulaska i procedurama biće objavljeno u preležanog virusa kovid-19, ili su narednim danima. negativni na PCR, odnosno brzom EXIT FESTIVALA testu. Organizovanje događaja uz ovakve uslove za sve festivale jedno u ime slobode, ljubavi, pri- odobrio je Krizni štab Republike jateljstva, nade, optimizma, i - po- Srbije. Postojaće pravila koja svi Ponovo bede! Na našoj Petrovaradinskoj moraju da se poštuju u cilju oču- tvrđavi, od 8. do 11. jula. vanja zdravlja i bezbednosti, i zato smo EXIT se ove godine organizuje je neophodna saradnja svih po- u dosad najkompleksnijim uslovi- setilaca. Više detalja o načinu ula- zajedno! ma. Pandemija koronavirusa je i ska i procedurama biće objavlje- dalje tema, ali život više ne može no u narednim danima. da čeka. Razdvojenost, neizve- Saglasnost za održavanje festi- Petrovaradinska tvrđava, snost, otuđenost konačno će vala u Srbiji i širom sveta napokon od 8. do 11. jula ustupiti mesto ogromnoj energiji budi optimizam i daje viziju po- koja se nagomilala u prethodnih vratka normalnom životu, a ujed- EXIT stiže! Ove godine nećemo 15 meseci. -

Trijumf Matije Dedića, Massima, Gordana Tudora Te Grupa Hladno

ISSN 1330–4747 ČASOPIS HRVATSKOGA DRUŠTVA SKLADATELJA | BROJ 196 | TRAVANJ 2016. | CIJENA 22 kn 00416 9 771330 474007 Nezadovoljstvo odlukom HRT–a Eurosong 2016. i hrvatski autori Nagrađeni novi naraštaji skladatelja Tibor Szirovicza Valerija Vranješ Juraj Marko Žerovnik Autorski koncerti HDS–a Alfi Kabiljo kao autor komorne klasične glazbe Tema broja: Porin 2016. Intervjui Mirela Priselac Remi, Trijumf Mile Kekin, Auguste Matije Dedića, Notografija Massima, Album za pjevanje i sviranje Gordana Tudora hitova Zrinka Tutića te grupa 63. Zagrebački festival Hladno pivo i Nagrada splitskom Elemental DUVAL neoromantičnom valu N E I JUL Usvojen Godišnji financijski plan za 2016. UVODNIK Riječ urednice Poštovani čitatelji, Uoči Božića 2015. u novom broju našega časo- pisa donosimo događaje koji su obilježili turbulentni prije- održana je izvanredna laz iz 2015. u 2016. godinu. Premda su sveprisutne poli- tičke mijene najsnažnije utje- cale na sve segmente naše- Skupština Hrvatskog ga društva, glazba kao da je uspjela ostati izvan toga. Čini se da njome i u ovo grubo vri- društva skladatelja jeme najviše vlada ljubav u naj- širem smislu riječi, kao tema, kao motivacija i kao poticaj za dvorani Hrvatskog no predsjedništvo Skupštine: Zoran Ju- nu na izmaku u kojoj je Društvo prosla- stvaranje. Već su Damir Marti- društva skladatelja ranić (predsjednik HDS–a), Ante Pecotić vilo svoju 70. obljetnicu, istaknuvši naj- nović Mrle te njegova životna i 17. prosinca 2015. (dopredsjednik HDS–a) i Antun Tomislav važnije projekte i uspjehe HDS–a. Kao profesionalna partnerica Ivan- održana je izvan- Šaban (glavni tajnik HDS–a) predstavi- jedan od izazova u budućnosti, glav- ka Mazurkijević obilježili go- redna skupština lo je najvažnije točke prijedloga financij- ni tajnik izdvojio je pozicioniranje sekto- dinu na odlasku zajedničkim Hrvatskog društva skog plana koji je jednoglasno usvojen. -

Yugonostalgic Against All Odds: Nostalgia for Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Among Young Leftist Activists in Contemporary Serbia

Yugonostalgic against All Odds: Nostalgia for Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia among Young Leftist Activists in Contemporary Serbia Nadiya Chushak Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2013 School of Social and Political Science The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper ii Abstract This thesis examines yugonostalgia – nostalgia for the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) – in contemporary Serbia. Yugonostalgia often has a negative reputation – both in academia and in everyday life – as an ‘unhealthy’ or even debilitating fixation on the socialist past. However, this thesis argues that yugonostalgia tells us not only about nostalgic subjects’ attitude towards the past but also about their current concerns. Contemporary Serbia is permeated by discourses privileging nationalistic and neoliberal values. This thesis explores how young people can develop nostalgic attitudes towards the socialist past, even in such an unlikely context. Yugonostalgia is an ambiguous phenomenon, and this ambiguity allows for positive dimensions and uses. To highlight the emancipatory potential of yugonostalgia, this thesis utilises ethnographic fieldwork among young leftist activists in Serbia’s capital, Belgrade. The focus on this milieu demonstrates how yugonostalgia is not simply reactionary but can overlap with and even energize a critical stance towards both nationalistic and neoliberal projects in contemporary Serbia. Additionally, this focus on young activists helps to counter popular negative stereotypes about Serbian youth as either passive victims of their situation or as a violent negative force. Finally, the thesis also adds to our understanding of how the meaning of the ‘left’ is negotiated in post-socialist conditions.