Considerations on the Influence of the Low Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

ASCI Newsl Oct 2017

+ Scotland! BOARD MEMBERS ASCI Newsletter President Karon Korp Vice President October 2017 Secretary Alice Keller Promoting International Partnerships Treasurer Jackie Craig Past President Andrew Craig Membership Bunny Cabaniss Social Chair Jacquie Nightingale Special Projects Gwen Hughes, Ken Richards Search Russ Martin Newsletter Jerry Plotkin Publicity / Public Relations Jeremy Carter Fund Development Marjorie McGuirk Giving Society Gwen Hughes George Keller Vladikavkaz, Russia Constance Richards San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexico Lori Davis Saumur, France Jessica Coffield Karpenisi, Greece Sophie Mills, Andrew Craig New Scottish sister city! Valladolid, Mexico Sybil Argintar A hug to seal the deal! Osogbo, Nigeria Sandra Frempong Katie Ryan Follow ASCI activities on the web! Dunkeld-Birnam Rick Lutovsky, Doug Orr http://ashevillesistercities.org Honorary Chairman Mayor Esther Manheimer Like us on Facebook – keep up with ASCI news. Mission Statement: Asheville Sister Cities, Inc. promotes peace, understanding, cooperation and sustainable partnerships through formalized agreements between International cities and the City of Asheville, North Carolina. Website: www.ashevillesistercities.org ASHEVILLE SISTER CITIES NEWSLETTER – OCTOBER 2017 page 2 On the cover: Surrounded by friends, Birnam-Dunkeld Committee Chair for Asheville Fiona Ritchie celebrates their new sister city with Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer. Message from the President by Karon Korp What an exciting Fall line-up we have, on the heels of a very busy summer! Our group from Asheville was warmly received by our new sister cities of Dunkeld and Birnam, Scotland in August. The celebration and signing event we held in September at Highland Brewing gave everyone a taste of the wonderful friendships now formed as we hosted our Scottish guests. -

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

The Digital Nature of Gothic

The Digital Nature of Gothic Lars Spuybroek Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic is inarguably the best-known book on Gothic architecture ever published; argumentative, persuasive, passionate, it’s a text influential enough to have empowered a whole movement, which Ruskin distanced himself from on more than one occasion. Strangely enough, given that the chapter we are speaking of is the most important in the second volume of The Stones of Venice, it has nothing to do with the Venetian Gothic at all. Rather, it discusses a northern Gothic with which Ruskin himself had an ambiguous relationship all his life, sometimes calling it the noblest form of Gothic, sometimes the lowest, depending on which detail, transept or portal he was looking at. These are some of the reasons why this chapter has so often been published separately in book form, becoming a mini-bible for all true believers, among them William Morris, who wrote the introduction for the book when he published it First Page of John Ruskin’s “The with his own Kelmscott Press. It is a precious little book, made with so much love and Nature of Gothic: a chapter of The Stones of Venice” (Kelmscott care that one hardly dares read it. Press, 1892). Like its theoretical number-one enemy, classicism, the Gothic has protagonists who write like partisans in an especially ferocious army. They are not your usual historians – the Gothic hasn’t been able to attract a significant number of the best historians; it has no Gombrich, Wölfflin or Wittkower, nobody of such caliber – but a series of hybrid and atypical historians such as Pugin and Worringer who have tried again and again, like Ruskin, to create a Gothic for the present, in whatever form: revivalist, expressionist, or, as in my case, digitalist, if that is a word. -

Gothic Churches in Paris St Gervais Et St Protais Image Matching 3D Reconstruction to Understand the Vaults System Geometry

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W4, 2015 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25-27 February 2015, Avila, Spain GOTHIC CHURCHES IN PARIS ST GERVAIS ET ST PROTAIS IMAGE MATCHING 3D RECONSTRUCTION TO UNDERSTAND THE VAULTS SYSTEM GEOMETRY M.Capone a, , M. Campi b, R. Catuogno c a DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] b DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] c DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] Commission V, WG V/4 KEY WORDS: Structure from Motion, Image Matching, 3D Modeling, Ribbed Vaults, Gothic Flamboyant, 3D reconstruction. ABSTRACT: This paper is part of a research about ribbed vaults systems in French Gothic Cathedrals. Our goal is to compare some different gothic cathedrals to understand the complex geometry of the ribbed vaults. The survey isn't the main objective but it is the way to verify the theoretical hypotheses about geometric configuration of the flamboyant churches in Paris. The survey method's choice generally depends on the goal; in this case we had to study many churches in a short time, so we chose 3D reconstruction method based on image dense stereo matching. This method allowed us to obtain the necessary information to our study without bringing special equipment, such as the laser scanner. The goal of this paper is to test image matching 3D reconstruction method in relation to some particular study cases and to show the benefits and the troubles. -

Pentagons in Medieval Architecture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Építés – Építészettudomány 46 (3–4) 291–318 DOI: 10.1556/096.2018.008 PENTAGONS IN MEDIEVAL ARCHITECTURE KRISZTINA FEHÉR* – BALÁZS HALMOS** – BRIGITTA SZILÁGYI*** *PhD student. Department of History of Architecture and Monument Preservation, BUTE K II. 82, Műegyetem rkp. 3, H-1111 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] **PhD, assistant professor. Department of History of Architecture and Monument Preservation, BUTE K II. 82, Műegyetem rkp. 3, H-1111 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] ***PhD, associate professor. Department of Geometry, BUTE H. II. 22, Egry József u. 1, H-1111 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] Among regular polygons, the pentagon is considered to be barely used in medieval architectural compositions, due to its odd spatial appearance and difficult method of construction. The pentagon, representing the number five has a rich semantic role in Christian symbolism. Even though the proper way of construction was already invented in the Antiquity, there is no evidence of medieval architects having been aware of this knowledge. Contemporary sources only show approximative construction methods. In the Middle Ages the form has been used in architectural elements such as window traceries, towers and apses. As opposed to the general opinion supposing that this polygon has rarely been used, numerous examples bear record that its application can be considered as rather common. Our paper at- tempts to give an overview of the different methods architects could have used for regular pentagon construction during the Middle Ages, and the ways of applying the form. -

The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE)

ABSTRACT MARY ELIZABETH BLUME The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE) The Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century in Europe aroused a debate concerning the origin of a style already six centuries old. Besides the underlying quandary of how to define or identify “Gothic” structures, the Victorian revivalists fought vehemently over the national birthright of the style. Although Gothic has been traditionally acknowledged as having French origins, English revivalists insisted on the autonomy of English Gothic as a distinct and independent style of architecture in origin and development. Surprisingly, nearly two centuries later, the debate over Gothic’s nationality persists, though the nationalistic tug-of-war has given way to the more scholarly contest to uncover the style’s authentic origins. Traditionally, scholarship took structural or formal approaches, which struggled to classify structures into rigidly defined periods of formal development. As the Gothic style did not develop in such a cleanly linear fashion, this practice of retrospective labeling took a second place to cultural approaches that consider the Gothic style as a material manifestation of an overarching conscious Gothic cultural movement. Nevertheless, scholars still frequently look to the Isle-de-France when discussing Gothic’s formal and cultural beginnings. Gothic historians have entered a period of reflection upon the field’s historiography, questioning methodological paradigms. This -

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Y\5$ in History

THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A5 In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree Mi ST Master of Arts . Y\5$ In History by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California May, 2016 Copyright by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Gargoyles of San Francisco: Medievalist Architecture in Northern California 1900-1940 by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr., and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History at San Francisco State University. <2 . d. rbel Rodriguez, lessor of History Philip Dreyfus Professor of History THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California 2016 After the fire and earthquake of 1906, the reconstruction of San Francisco initiated a profusion of neo-Gothic churches, public buildings and residential architecture. This thesis examines the development from the novel perspective of medievalism—the study of the Middle Ages as an imaginative construct in western society after their actual demise. It offers a selection of the best known neo-Gothic artifacts in the city, describes the technological innovations which distinguish them from the medievalist architecture of the nineteenth century, and shows the motivation for their creation. The significance of the California Arts and Crafts movement is explained, and profiles are offered of the two leading medievalist architects of the period, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan. -

Dornochyou Can Do It All from Here

DornochYou can do it all from here The Highlands in miniature only 2 miles off the NC500 & one hour from Inverness Visit Dornoch, an historic Royal Burgh with a 13th century Cathedral, Castle, Jail & Courthouse in golden sandstone, all nestled round the green and Square where we hold summer markets and the pipe band plays on Saturday evenings. Things to do Historylinks Museum Historylinks Trail Discover 7,000 years of Explore the town through 16 Dornoch’s turbulent past in heritage sites with display our Visit Scotland 5 star panels. Pick up a leaflet and rated museum. map at the museum. Royal Dornoch Golf Club Dornoch Cathedral Golf has been played here for Gilbert de Moravia began over 400 years. building the Cathedral in 1224. The championship course is Following clan feuds it fell into rated #1 in Scotland and #4 in disrepair and was substantially the World by Golf Digest. restored in the 1800s. Aspen Spa Experience Dornoch & Embo Beaches Take some time out and relax Enjoy miles of unspoilt with a luxury spa, beauty beaches - ideal for making treatment or specialist golf sandcastles with the children massage. Gifts, beauty and spa or just walking the dog. products available in the shop. Events Calendar 2019 Car Boot Sales Community Markets The last Saturday of the month The 2nd Wednesday of the February, April, June, August month May to September, also & October fourth Wednesday June, July Dornoch Social Club & August. Cathedral Green 9:30 am - 12:30 pm 9:30 am - 1 pm Fibre Fest 8 - 10- March Dornoch Pipe Band Master classes, learning Parade on most Saturday techniques and drop in evenings from the 25th May to sessions. -

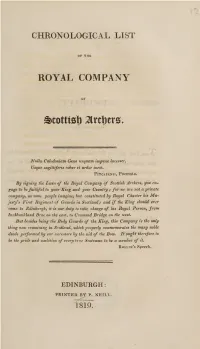

Chronological List of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF THE ROYAL COMPANY OF 2lrrt)er0. Nulla Caledoniam Gens unquarn impune laces set, Usque sagittiferis rohur et ardor inest. Pitcairnii, Poemata. By signing the Laws of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers, you en¬ gage to he faithful to your King and your Country ; for we are not a private company, as some people imagine, but constituted hy Royal Charter his Ma¬ jesty's First Regiment of Guards in Scotland; and if the King should ever come to Edinburgh, it is our duty to take charge of his Royal Person, from Inchbunkland Brae on the east, to Cramond Bridge on the west. But besides being the Body Guards of the King, this Company is the only thing now remaining in Scotland, which properly commemorates the many noble deeds performed by our ancestors by the aid of the Bow. It ought therefore to be the pride and ambition of every true Scotsman to be a member of it. Roslin’s Speech. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY P. NEII.T.. 1819. PREFACE, T he first part of the following List, is not preserved in the handwriting of the Members themselves, and is not accurate with respect to dates; but the names are copied from the oldest Minute-books of the Company which have been preserved. The list from the 13th of May 1714, is copied from the Parchment Roll, which every Member subscribes with his own hand, in presence of the Council of the Company, when he receives his Diploma. Edinburgh, 1 5th July 1819* | f I LIST OF MEMBERS ADMITTED INTO THE ROYAL COMPANY OF SCOTTISH ARCHERS, FROM 1676, Extracted from Minute-books prior to the 13th of May 1714.