Teacher's Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dornoch Firth Campus December 2019

Hello As we fast approach the Christmas break we would like to take a little time to reflect on the successes and achievements of our whole school community. Many of our children, young people and colleagues have received recognition for their creativity and hard work. A special congratulations should be made to Dr Allan for his international work. Well done also to Joan Murray at Bonar Bridge Primary who received Public Servant of the Year award, and also to Howard Tolliday for his recent recognition in the UK Salters' National Awards for Science Technicians. Finally, I would also like to extend a special thank you to our brilliant librarian, Fiona Macleod, who is always looking for new and creative ways of engaging children and young people in reading. The atmosphere in the library is wonderful and it is great to see so many young people interested in books. Fiona’s work has been complemented by our primary school teachers who have been presenting lively and engaging assemblies over the last few months. The children are developing their confidence in public speaking and this will support their studies and aspirations later in their school and career pathways. It was great to see so many of you at the recent family event and we welcome your feedback on how we can continue to develop events and activities which support our partnership and learning at home. If you are interested in presenting or running an event please do not hesitate to contact us. In S3, we hope to meet many of you on Tuesday 3 December during our Learner Journey Review Event which will run from 9.00 am until 7.00 pm. -

Rosehall Information

USEFUL TELEPHONE NUMBERS Rosehall Information POLICE Emergency = 999 Non-emergency NHS 24 = 111 No 21 January 2021 DOCTORS Dr Aline Marshall and Dr Scott Smith PLEASE BE AWARE THAT, DUE TO COVID-RELATED RESTRICTIONS Health Centre, Lairg: tel 01549 402 007 ALL TIMES LISTED SHOULD BE CHECKED Drs C & J Mair and Dr S Carbarns This Information Sheet is produced for the benefit of all residents of Creich Surgery, Bonar Bridge: tel 01863 766 379 Rosehall and to welcome newcomers into our community DENTISTS K Baxendale / Geddes: 01848 621613 / 633019 Kirsty Ramsey, Dornoch: 01862 810267; Dental Laboratory, Dornoch: 01862 810667 We have a Village email distribution so that everyone knows what is happening – Golspie Dental Practice: 01408 633 019; Sutherland Dental Service, Lairg: 402 543 if you would like to be included please email: Julie Stevens at [email protected] tel: 07927 670 773 or Main Street, Lairg: PHARMACIES 402 374 (freephone: 0500 970 132) Carol Gilmour at [email protected] tel: 01549 441 374 Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge: 01863 760 011 Everything goes out under “blind” copy for privacy HOSPITALS / Raigmore, Inverness: 01463 704 000; visit 2.30-4.30; 6.30-8.30pm There is a local residents’ telephone directory which is available from NURSING HOMES Lawson Memorial, Golspie: 01408 633 157 & RESIDENTIAL Wick (Caithness General): 01955 605 050 the Bradbury Centre or the Post Office in Bonar Bridge. Cambusavie Wing, Golspie: 01408 633 182; Migdale, Bonar Bridge: 01863 766 211 All local events and information can be found in the -

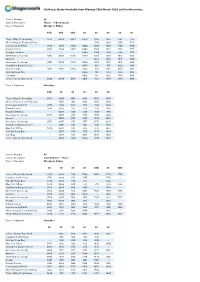

Caithness Guide Timetable from Monday 23Rd March 2020 Until Further Notice

Caithness Guide timetable from Monday 23rd March 2020 until further notice. Service Number 80 Service Description Thurso - John O Groats Days of Operation Monday to Friday 80D 80D 80D 80 80 80 80 80 Thurso Olrig St Santander 0551 0608 0640 0830 1025 1235 1545 1735 Mount Pleasant Towerhill Road - - - - 1030 1240 1550 1740 Castletown Drill Hall 0601 0618 0650 0840 1039 1249 1559 1749 Dunnet Corner 0607 0624 0656 0846 1045 1255 1605 1755 Brough Letterbox - - - 0849 1048 1258 1608 1758 Greenvale Crossroads 0611 0628 0700 0854 1053 1303 1613 1803 Barrock - - - - 1055 1305 1616 1806 Greenvale Crossroads 0611 0628 0700 0854 1057 1307 1618 1808 Scarfskerry Baptist Church - - - 0858 1101 1311 1622 1812 Mey Post Office 0615 0632 0704 904 1107 1317 1628 1818 Gills Bay Road End - - - 0909 1113 1323 1634 1824 Canisbay - - - 0912 1117 1327 1638 1828 John o' Groats Bus Stand 0626 0643 0715 0918 1124 1334 1645 1835 Days of Operation Saturdays 80D 80 80 80 80 80 Thurso Olrig St Santander 0725 0905 1105 1305 1505 1755 Mount Pleasant Towerhill Road - 0910 1110 1310 1510 1800 Castletown Drill Hall 0735 0919 1119 1319 1519 1809 Dunnet Corner 0741 0925 1125 1325 1525 1815 Brough Letterbox - 0928 1128 1328 1528 1818 Greenvale Crossroads 0745 0933 1133 1333 1533 1823 Barrock - 0935 1135 1335 1535 1825 Greenvale Crossroads 0745 0937 1137 1337 1537 1827 Scarfskerry Baptist Church - 0941 1141 1341 1541 1831 Mey Post Office 0749 0947 1147 1347 1547 1837 Gills Bay Road End - 0953 1153 1353 1553 1843 Canisbay - 0957 1157 1357 1557 1847 John o' Groats Bus Stand - 1004 -

Habitats Regulations Appraisal (HRA) on the Moray Firth a Guide for Developers and Regulators

Scottish Natural Heritage Habitats Regulations Appraisal (HRA) on the Moray Firth A Guide for developers and regulators Photo: Donald M Fisher Contents Section 1 Introduction 4 Introduction 4 Section 2 Potential Pathways of Impact 6 Construction 6 Operation 6 Table 1 Generic impact pathways and mitigation to consider 7 Section 3 Ecological Principles 9 Habitats and physical processes 9 Management of the environment 10 Land claim and physical management of the intertidal 10 Dredging and Disposal 11 Disturbance – its ecological consequences 12 Types of disturbance 12 Disturbance whilst feeding 13 Disturbance at resting sites 14 Habituation and prevention 14 Section 4 Habitats Regulations Appraisal (HRA) 15 Natura 2000 15 The HRA procedure 16 HRA in the Moray Firth area 17 Figure 1 The HRA process up to and including appropriate assessment 18 The information required 19 Determining that there are no adverse effects on site integrity 19 Figure 2 The HRA process where a Competent Authority wishes to consent to a plan or project, but cannot conclude that there is no adverse effect on site integrity 20 1 Section 5 Accounts for Qualifying Interests 21 Habitats 21 Atlantic salt meadows 21 Coastal dune heathland 22 Lime deficient dune heathland with crowberry 23 Embryonic shifting dunes 24 Shifting dunes with marram 25 Dune grassland 26 Dunes with juniper 27 Humid dune slacks 28 Coastal shingle vegetation outside the reach of waves 29 Estuaries 30 Glasswort and other annuals colonising mud and sand 31 Intertidal mudflats and sandflats 32 Reefs 33 -

Prospectus Session 2019/20

DORNOCH FIRTH CAMPUS PROSPECTUS SESSION 2019/20 Head Teacher 3-18 Miss Tina Stones BA(Hons), BSc(Hons), MSc, PGCE Dornoch Academy Tel: 01862 810246 Evelix Road E-mail: [email protected] Dornoch Website: www.dornochacademy.com Sutherland Schools Information Service: 0800 564 2272 (PIN 041020) IV25 3HR Depute Head Teacher: Mrs K Birnie Bonar Bridge Primary School/Nursery Tel (Primary): 01862 812908 Migdale Road Tel (Nursery): 07708 402494 Bonar Bridge E-mail: [email protected] IV24 3AP Website: www.bonarbridgeprimary.wordpress.com Schools Information Service: 0800 564 2272 (PIN 041550) Depute Head Teacher: Mr A Sergeant Dornoch Primary School/Nursery Tel (Primary): 01862 812901 Evelix Road Tel (Nursery): 07880 893616 Dornoch E-mail: [email protected] Sutherland Website: www.dornochprimary.com IV25 3HR Schools Information Service: 0800 564 2272 (PIN 041890) Depute Head Teacher (Primary): Mr N Ross Depute Head Teacher (Nursery): Mr A Sergeant Whilst the information in this document is considered to be true and correct at the date of publication, changes in circumstances after the time of publication may impact on the accuracy of the information. CONTENTS SECTION 1: USEFUL INFORMATION 1 SCHOOL TYPE 4 2 INITIAL CONTACTS 4 3 INTRODUCTION 4 4 STAFF 5 5 SCHOOL CALENDAR 6 6 SCHOOL MEALS 7 7 PROTECTION OF CHILDREN 7 .1 Pupils in School 7 .2 Pupils Moving Away From School 7 8 PROCEDURES FOR POTENTIAL DRUGS MISUSE INCIDENTS 8 9 DATA PROTECTION 8 .1 Access to Pupil Records 8 .2 Data Protection Legislation -

Highland Archaeology Festival Fèis Arc-Eòlais Na Gàidhealtachd

Events guide Iùl thachartasan Highland Archaeology Festival Fèis Arc-eòlais na Gàidhealtachd 29th Sept -19th Oct2018 Celebrating Archaeology,Historyand Heritage A’ Comharrachadh Arc-eòlas,Eachdraidh is Dualchas Archaeology Courses The University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute Access, degree, masters and postgraduate research available at the University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute. www.uhi.ac.uk/en/archaeology-institute/ Tel: 01856 569225 Welcome to Highland Archaeology Festival 2018 Fàilte gu Fèis Arc-eòlais na Gàidhealtachd 2018 I am pleased to introduce the programme for this year’s Highland Archaeology Festival which showcases all of Highland’s historic environment from buried archaeological remains to canals, cathedrals and more. The popularity of our annual Highland Archaeology Festival goes on from strength to strength. We aim to celebrate our shared history, heritage and archaeology and showcase the incredible heritage on our doorsteps as well as the importance of protecting this for future generations. The educational and economic benefits that this can bring to communities cannot be overstated. New research is being carried out daily by both local groups and universities as well as in advance of construction. Highland Council is committed to letting everyone have access to the results of this work, either through our Historic Environment Record (HER) website or through our programme of events for the festival. Our keynote talks this year provide a great illustration of the significance of Highland research to the wider, national picture. These lectures, held at the council chamber in Inverness, will cover the prehistoric period, the early medieval and the industrial archaeology of more recent times. -

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

Dornochyou Can Do It All from Here

DornochYou can do it all from here The Highlands in miniature only 2 miles off the NC500 & one hour from Inverness Visit Dornoch, an historic Royal Burgh with a 13th century Cathedral, Castle, Jail & Courthouse in golden sandstone, all nestled round the green and Square where we hold summer markets and the pipe band plays on Saturday evenings. Things to do Historylinks Museum Historylinks Trail Discover 7,000 years of Explore the town through 16 Dornoch’s turbulent past in heritage sites with display our Visit Scotland 5 star panels. Pick up a leaflet and rated museum. map at the museum. Royal Dornoch Golf Club Dornoch Cathedral Golf has been played here for Gilbert de Moravia began over 400 years. building the Cathedral in 1224. The championship course is Following clan feuds it fell into rated #1 in Scotland and #4 in disrepair and was substantially the World by Golf Digest. restored in the 1800s. Aspen Spa Experience Dornoch & Embo Beaches Take some time out and relax Enjoy miles of unspoilt with a luxury spa, beauty beaches - ideal for making treatment or specialist golf sandcastles with the children massage. Gifts, beauty and spa or just walking the dog. products available in the shop. Events Calendar 2019 Car Boot Sales Community Markets The last Saturday of the month The 2nd Wednesday of the February, April, June, August month May to September, also & October fourth Wednesday June, July Dornoch Social Club & August. Cathedral Green 9:30 am - 12:30 pm 9:30 am - 1 pm Fibre Fest 8 - 10- March Dornoch Pipe Band Master classes, learning Parade on most Saturday techniques and drop in evenings from the 25th May to sessions. -

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol. 22 : Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies 1 Vol. 22: Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh (East Sutherland & Caithness) Author: Kurt C. Duwe 2nd Edition January, 2012 Executive Summary This publication is part of a series dealing with local communities which were predominantly Gaelic- speaking at the end of the 19 th century. Based mainly (but not exclusively) on local population census information the reports strive to examine the state of the language through the ages from 1881 until to- day. The most relevant information is gathered comprehensively for the smallest geographical unit pos- sible and provided area by area – a very useful reference for people with interest in their own communi- ty. Furthermore the impact of recent developments in education (namely teaching in Gaelic medium and Gaelic as a second language) is analysed for primary school catchments. Gaelic once was the dominant means of conversation in East Sutherland and the western districts of Caithness. Since the end of the 19 th century the language was on a relentless decline caused both by offi- cial ignorance and the low self-confidence of its speakers. A century later Gaelic is only spoken by a very tiny minority of inhabitants, most of them born well before the Second World War. Signs for the future still look not promising. Gaelic is still being sidelined officially in the whole area. Local council- lors even object to bilingual road-signs. Educational provision is either derisory or non-existent. Only constant parental pressure has achieved the introduction of Gaelic medium provision in Thurso and Bonar Bridge. -

Cormack, Wade

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Sport and Physical Education in the Northern Mainland Burghs of Scotland c. 1600-1800 Cormack, Wade DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2016 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Sport and Physical Education in the Northern Mainland Burghs of Scotland c. -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register This guide is to help you fill in your application form for Highland Housing Register. It also gives you some information about social rented housing in Highland, as well as where to find out more information if you need it. This form is available in other formats such as audio tape, CD, Braille, and in large print. It can also be made available in other languages. Contents PAGE 1. About Highland Housing Register .........................................................................................................................................1 2. About Highland House Exchange ..........................................................................................................................................2 3. Contacting the Housing Option Team .................................................................................................................................2 4. About other social, affordable and supported housing providers in Highland .......................................................2 5. Important Information about Welfare Reform and your housing application ..............................................3 6. Proof - what and why • Proof of identity ...............................................................................................................................4 • Pregnancy ...........................................................................................................................................5 • Residential access to children