Habitats Regulations Appraisal (HRA) on the Moray Firth a Guide for Developers and Regulators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divided We Stand POLITEIA

Peter Fraser Divided We Stand Scotland a Nation Once Again? POLITEIA A FORUM FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC THINKING POLITEIA A Forum for Social and Economic Thinking Politeia commissions and publishes discussions by specialists about social and economic ideas and policies. It aims to encourage public discussion on the relationship between the state and the people. Its aim is not to influence people to support any given political party, candidates for election, or position in a referendum, but to inform public discussion of policy. The forum is independently funded, and the publications do not express a corporate opinion, but the views of their individual authors. www.politeia.co.uk Divided We Stand Scotland a Nation Once Again? Peter Fraser POLITEIA 2012 First published in 2012 by Politeia 33 Catherine Place London SW1E 6DY Tel. 0207 799 5034 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.politeia.co.uk © Politeia 2012 Essay Series ISBN 978-0-9571872-0-7 Cover design by John Marenbon Printed in Great Britain by: Plan – IT Reprographics Atlas House Cambridge Place Hills Road Cambridge CB2 1NS THE AUTHOR Lord Fraser of Carmyllie QC Lord Fraser of Carmyllie QC was the Conservative Member of Parliament for Angus South (1979-83) and Angus East (1983-87) and served as Solicitor General for Scotland from 1982-88. He became a peer in 1989 and served as Lord Advocate (1989-92), Minister of State at the Scottish Office (1992-95) and the Department of Trade and Industry (1995-97). He was Deputy Leader of the Opposition from 1997-98. His publications include The Holyrood Inquiry, a 2004 report on the Holyrood building project. -

Simplicity at Our Core

SIMPLICITY AT OUR CORE PORTFOLIO Contents OUR BUILDINGS Findhorn•Sands, p3 Bonlokke, p10 Social Bite Homeless Village, p17 Bonsall, p4 Mackinnon, p11 Nedd House, p18 Dionard, p5 Salvesen, p12 Dyson IET, p19 Hill•Cottage, p6 Woodlands Workspace (Artists Hub), p13 Virtual Reality, p20 Alness, p7 Helmsdale•Recording Studio, p14 Team, p21 Kingsmills, p8 Findhorn•Eco•Wedge, p15 Fit•Homes, p16 Unit 17 Cromarty Firth Industrial Park, Bunchrew, p9 Invergordon, UK, IV18 0LT About Us Carbon Dynamic is a world leader in modular timber manufacture. “Our goal is to provide everything you will ever need to achieve your build under the one roof. We strive to free ourselves from the complexity At Carbon Dynamic we design and manufacture beautiful timber and intricacy of the traditional build process believing the simpler the modular buildings with exceptional levels of insulation, airtightness and process the less stressful and more enjoyable it becomes”. sustainability. We’re dedicated to providing cost effective, low energy Matt Stevenson, Director buildings using locally-sourced and sustainable materials. Findhorn Eco Lodges Part of the long-term development adjacent to the sand dunes of Findhorn, each of these lodges are individually owned and designed. Laid to a Findhorn, Scotland curve, each lodge has its own unique views and high levels of privacy. Although externally similar the design of these lodges is so flexible that 1,2 or Residential, 2015 3 bedroom or even completely open-planned layouts are possible. Unit 17 Cromarty Firth Industrial Park, Invergordon, UK, IV18 0LT 3 Bonsall Eco Lodge Contemporary, open plan living with oak floors. Painted in calming tones and everything a guest should require for a comfortable and enjoyable Brodie, Scotland stay, with the capacity to accommodate four guests. -

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall IV7

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall Achbeag, Outside The property is approached over a tarmacadam Cullicudden, Balblair, driveway providing parking for multiple vehicles Dingwall IV7 8LL and giving access to the integral double garage. Surrounding the property, the garden is laid A detached, flexible family home in a mainly to level lawn bordered by mature shrubs popular Black Isle village with fabulous and trees and features a garden pond, with a wide range of specimen planting, a wraparound views over Cromarty Firth and Ben gravelled terrace, patio area and raised decked Wyvis terrace, all ideal for entertaining and al fresco dining, the whole enjoying far-reaching views Culbokie 5 miles, A9 5 miles, Dingwall 10.5 miles, over surrounding countryside. Inverness 17 miles, Inverness Airport 24 miles Location Storm porch | Reception hall | Drawing room Cullicudden is situated on the Black Isle at Sitting/dining room | Office | Kitchen/breakfast the edge of the Cromarty Firth and offers room with utility area | Cloakroom | Principal spectacular views across the firth with its bedroom with en suite shower room | Additional numerous sightings of seals and dolphins to bedroom with en suite bathroom | 3 Further Ben Wyvis which dominates the skyline. The bedrooms | Family shower room | Viewing nearby village of Culbokie has a bar, restaurant, terrace | Double garage | EPC Rating E post office and grocery store. The Black Isle has a number of well regarded restaurants providing local produce. Market shopping can The property be found in Dingwall while more extensive Achbeag provides over 2,200 sq. ft. of light- shopping and leisure facilities can be found in filled flexible accommodation arranged over the Highland Capital of Inverness, including two floors. -

Rosehall Information

USEFUL TELEPHONE NUMBERS Rosehall Information POLICE Emergency = 999 Non-emergency NHS 24 = 111 No 21 January 2021 DOCTORS Dr Aline Marshall and Dr Scott Smith PLEASE BE AWARE THAT, DUE TO COVID-RELATED RESTRICTIONS Health Centre, Lairg: tel 01549 402 007 ALL TIMES LISTED SHOULD BE CHECKED Drs C & J Mair and Dr S Carbarns This Information Sheet is produced for the benefit of all residents of Creich Surgery, Bonar Bridge: tel 01863 766 379 Rosehall and to welcome newcomers into our community DENTISTS K Baxendale / Geddes: 01848 621613 / 633019 Kirsty Ramsey, Dornoch: 01862 810267; Dental Laboratory, Dornoch: 01862 810667 We have a Village email distribution so that everyone knows what is happening – Golspie Dental Practice: 01408 633 019; Sutherland Dental Service, Lairg: 402 543 if you would like to be included please email: Julie Stevens at [email protected] tel: 07927 670 773 or Main Street, Lairg: PHARMACIES 402 374 (freephone: 0500 970 132) Carol Gilmour at [email protected] tel: 01549 441 374 Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge: 01863 760 011 Everything goes out under “blind” copy for privacy HOSPITALS / Raigmore, Inverness: 01463 704 000; visit 2.30-4.30; 6.30-8.30pm There is a local residents’ telephone directory which is available from NURSING HOMES Lawson Memorial, Golspie: 01408 633 157 & RESIDENTIAL Wick (Caithness General): 01955 605 050 the Bradbury Centre or the Post Office in Bonar Bridge. Cambusavie Wing, Golspie: 01408 633 182; Migdale, Bonar Bridge: 01863 766 211 All local events and information can be found in the -

Firth of Lorn Management Plan

FIRTH OF LORN MARINE SAC OF LORN MARINE SAC FIRTH ARGYLL MARINE SPECIAL AREAS OF CONSERVATION FIRTH OF LORN MANA MARINE SPECIAL AREA OF CONSERVATION GEMENT PLAN MANAGEMENT PLAN CONTENTS Executive Summary 1. Introduction CONTENTS The Habitats Directive 1.1 Argyll Marine SAC Management Forum 1.2 Aims of the Management Plan 1.3 2. Site Overview Site Description 2.1 Reasons for Designation: Rocky Reef Habitat and Communities 2.2 3. Management Objectives Conservation Objectives 3.1 Sustainable Economic Development Objectives 3.2 4. Activities and Management Measures Management of Fishing Activities 4.1 Benthic Dredging 4.1.1 Benthic Trawling 4.1.2 Creel Fishing 4.1.3 Bottom Set Tangle Nets 4.1.4 Shellfish Diving 4.1.5 Management of Gathering and Harvesting 4.2 Shellfish and Bait Collection 4.2.1 Harvesting/Collection of Seaweed 4.2.2 Management of Aquaculture Activities 4.3 Finfish Farming 4.3.1 Shellfish Farming 4.3.2 FIRTH OF LORN Management of Recreation and Tourism Activities 4.4 Anchoring and Mooring 4.4.1 Scuba Diving 4.4.2 Charter Boat Operations 4.4.3 Management of Effluent Discharges/Dumping 4.5 Trade Effluent 4.5.1 CONTENTS Sewage Effluent 4.5.2 Marine Littering and Dumping 4.5.3 Management of Shipping and Boat Maintenance 4.6 Commercial Marine Traffic 4.6.1 Boat Hull Maintenance and Antifoulant Use 4.6.2 Management of Coastal Development/Land-Use 4.7 Coastal Development 4.7.1 Agriculture 4.7.2 Forestry 4.7.3 Management of Scientific Research 4.8 Scientific Research 4.8.1 5. -

Caithness Guide Timetable from Monday 23Rd March 2020 Until Further Notice

Caithness Guide timetable from Monday 23rd March 2020 until further notice. Service Number 80 Service Description Thurso - John O Groats Days of Operation Monday to Friday 80D 80D 80D 80 80 80 80 80 Thurso Olrig St Santander 0551 0608 0640 0830 1025 1235 1545 1735 Mount Pleasant Towerhill Road - - - - 1030 1240 1550 1740 Castletown Drill Hall 0601 0618 0650 0840 1039 1249 1559 1749 Dunnet Corner 0607 0624 0656 0846 1045 1255 1605 1755 Brough Letterbox - - - 0849 1048 1258 1608 1758 Greenvale Crossroads 0611 0628 0700 0854 1053 1303 1613 1803 Barrock - - - - 1055 1305 1616 1806 Greenvale Crossroads 0611 0628 0700 0854 1057 1307 1618 1808 Scarfskerry Baptist Church - - - 0858 1101 1311 1622 1812 Mey Post Office 0615 0632 0704 904 1107 1317 1628 1818 Gills Bay Road End - - - 0909 1113 1323 1634 1824 Canisbay - - - 0912 1117 1327 1638 1828 John o' Groats Bus Stand 0626 0643 0715 0918 1124 1334 1645 1835 Days of Operation Saturdays 80D 80 80 80 80 80 Thurso Olrig St Santander 0725 0905 1105 1305 1505 1755 Mount Pleasant Towerhill Road - 0910 1110 1310 1510 1800 Castletown Drill Hall 0735 0919 1119 1319 1519 1809 Dunnet Corner 0741 0925 1125 1325 1525 1815 Brough Letterbox - 0928 1128 1328 1528 1818 Greenvale Crossroads 0745 0933 1133 1333 1533 1823 Barrock - 0935 1135 1335 1535 1825 Greenvale Crossroads 0745 0937 1137 1337 1537 1827 Scarfskerry Baptist Church - 0941 1141 1341 1541 1831 Mey Post Office 0749 0947 1147 1347 1547 1837 Gills Bay Road End - 0953 1153 1353 1553 1843 Canisbay - 0957 1157 1357 1557 1847 John o' Groats Bus Stand - 1004 -

The Case for a Marine Act for Scotland the Tangle of the Forth

The Case for a Marine Act for Scotland The Tangle of the Forth © WWF Scotland For more information contact: WWF Scotland Little Dunkeld Dunkeld Perthshire PH8 0AD t: 01350 728200 f: 01350 728201 The Case for a Marine Act for Scotland wwf.org.uk/scotland COTLAND’S incredibly Scotland’s territorial rich marine environment is waters cover 53 per cent of Designed by Ian Kirkwood Design S one of the most diverse in its total terrestrial and marine www.ik-design.co.uk Europe supporting an array of wildlife surface area Printed by Woods of Perth and habitats, many of international on recycled paper importance, some unique to Scottish Scotland’s marine and WWF-UK registered charity number 1081274 waters. Playing host to over twenty estuarine environment A company limited by guarantee species of whales and dolphins, contributes £4 billion to number 4016274 the world’s second largest fish - the Scotland’s £64 billion GDP Panda symbol © 1986 WWF – basking shark, the largest gannet World Wide Fund for Nature colony in the world and internationally 5.5 million passengers and (formerly World Wildlife Fund) ® WWF registered trademark important numbers of seabirds and seals 90 million tonnes of freight Scotland’s seas also contain amazing pass through Scottish ports deepwater coral reefs, anemones and starfish. The rugged coastline is 70 per cent of Scotland’s characterised by uniquely varied habitats population of 5 million live including steep shelving sea cliffs, sandy within 0km of the coast and beaches and majestic sea lochs. All of 20 per cent within km these combined represent one of Scotland’s greatest 25 per cent of Scottish Scotland has over economic and aesthetic business, accounting for 11,000km of coastline, assets. -

Rod Kinnermony Bends

Document: Form 113 Issue: 1 Record of Determination Related to: All Contracts Page No. 1 of 64 A9 Kessock Bridge 5 year Maintenance Programme Record of Determination Name Organisation Signature Date Redacted Redacted 08/03/2018 Prepared By BEAR Scotland 08/08/2018 Redacted 03/09/2018 Checked By Jacobs Redacted 10/09/2018 Client: Transport Scotland Distribution Organisation Contact Copies BEAR Scotland Redacted 2 Transport Scotland Redacted 1 BEAR Scotland Limited experience that delivers Transport Scotland Trunk Road and Bus Operations Document: EC DIRECTIVE 97/11 (as amended) ROADS (SCOTLAND) ACT 1984 (as amended) RECORD OF DETERMINATION Name of Project: Location: A9 Kessock Bridge 5 year Maintenance A9 Kessock Bridge, Inverness Programme Marine Licence Application Structures: A9 Kessock Bridge Description of Project: BEAR Scotland are applying for a marine licence to cover a 5-year programme of maintenance works on the A9 Kessock Bridge, Inverness. The maintenance activities are broken down into ‘scheme’ and ‘cyclic maintenance’. ‘Scheme’ represents those works that will be required over the next 5 years, whilst ‘cyclic maintenance’ represents those works which may be required over the same timeframe. Inspections will also be carried out to identify the degree of maintenance activity required. Following review of detailed bathymetric data obtained in August 2018, BEAR Scotland now anticipate that scour repairs at Kessock Bridge are unlikely to be required within the next 5 five years; hence, this activity is considered cyclic maintenance. The activities encompass the following: Schemes • Fender replacement; • Superstructure painting and • Cable stay painting. Cyclic maintenance • Scour repairs; • Drainage cleaning; • Bird guano removal; • Structural bolt and weld renewal; • Mass damper re-tuning; • Pendel bearing inspection; • Cleaning and pressure washing superstructure • Cable stay re-tensioning; • Minor bridge maintenance. -

Swales Et Al. Sediment Process and Mangrove Expansion

SEDIMENT PROCESSES AND MANGROVE-HABITAT EXPANSION ON A RAPIDLY-PROGRADING MUDDY COAST, NEW ZEALAND Andrew Swales1, Samuel J. Bentley 2, Catherine Lovelock 3, Robert G. Bell 1 1. NIWA, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 11-115 Hamilton, New Zealand. [email protected] , [email protected] 2. Earth-Sciences Department, 6010 Alexander Murray Building, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St John’s NL, Canada A1B 3X5. [email protected] 3. Centre for Marine Studies, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, QLD 4072, Australia. [email protected] Abstract : Mangrove-habitat expansion has occurred rapidly over the last 50 years in the 800 km 2 Firth-of-Thames estuary (New Zealand). Mangrove forest now extends 1-km seaward of the 1952 shoreline. The geomorphic development of this muddy coast was reconstructed using dated cores ( 210 Pb, 137 Cs, 7Be), historical- aerial photographs and field observations to explore the interaction between sediment processes and mangrove ecology. Catchment deforestation (1850s–1920s) delivered millions of m 3 of mud to the Firth, with the intertidal flats accreting at 20 mm yr -1 before mangrove colonization began (mid-1950s) and sedimentation rates increased to ≤ 100 mm yr -1. 210 Pb data show that the mangrove forest is a major long-term sink for mud. Seedling recruitment on the mudflat is controlled by wave-driven erosion. Mangrove-habitat expansion has occurred episodically and likely coincides with calm weather. The fate of this mangrove ecosystem will depend on vertical accretion at a rate equal to or exceeding sea level rise. -

Prospectus Session 2019/20

DORNOCH FIRTH CAMPUS PROSPECTUS SESSION 2019/20 Head Teacher 3-18 Miss Tina Stones BA(Hons), BSc(Hons), MSc, PGCE Dornoch Academy Tel: 01862 810246 Evelix Road E-mail: [email protected] Dornoch Website: www.dornochacademy.com Sutherland Schools Information Service: 0800 564 2272 (PIN 041020) IV25 3HR Depute Head Teacher: Mrs K Birnie Bonar Bridge Primary School/Nursery Tel (Primary): 01862 812908 Migdale Road Tel (Nursery): 07708 402494 Bonar Bridge E-mail: [email protected] IV24 3AP Website: www.bonarbridgeprimary.wordpress.com Schools Information Service: 0800 564 2272 (PIN 041550) Depute Head Teacher: Mr A Sergeant Dornoch Primary School/Nursery Tel (Primary): 01862 812901 Evelix Road Tel (Nursery): 07880 893616 Dornoch E-mail: [email protected] Sutherland Website: www.dornochprimary.com IV25 3HR Schools Information Service: 0800 564 2272 (PIN 041890) Depute Head Teacher (Primary): Mr N Ross Depute Head Teacher (Nursery): Mr A Sergeant Whilst the information in this document is considered to be true and correct at the date of publication, changes in circumstances after the time of publication may impact on the accuracy of the information. CONTENTS SECTION 1: USEFUL INFORMATION 1 SCHOOL TYPE 4 2 INITIAL CONTACTS 4 3 INTRODUCTION 4 4 STAFF 5 5 SCHOOL CALENDAR 6 6 SCHOOL MEALS 7 7 PROTECTION OF CHILDREN 7 .1 Pupils in School 7 .2 Pupils Moving Away From School 7 8 PROCEDURES FOR POTENTIAL DRUGS MISUSE INCIDENTS 8 9 DATA PROTECTION 8 .1 Access to Pupil Records 8 .2 Data Protection Legislation -

Highland Council Area Report

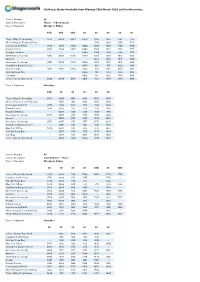

1. 2. NFI Provisional Report NFI 25-year projection of timber availability in the Highland Council Area Issued by: National Forest Inventory, Forestry Commission, 231 Corstorphine Road, Edinburgh, EH12 7AT Date: December 2014 Enquiries: Ben Ditchburn, 0300 067 5064 [email protected] Statistician: Alan Brewer, [email protected] Website: www.forestry.gov.uk/inventory www.forestry.gov.uk/forecast NFI Provisional Report Summary This report provides a detailed picture of the 25-year forecast of timber availability for the Highland Council Area. Although presented for different periods, these estimates are effectively a subset of those published as part of the 50-year forecast estimates presented in the National Forest Inventory (NFI) 50-year forecasts of softwood timber availability (2014) and 50-year forecast of hardwood timber availability (2014) reports. NFI reports are published at www.forestry.gov.uk/inventory. The estimates provided in this report are provisional in nature. 2 NFI 25-year projection of timber availability in the Highland Council Area NFI Provisional Report Contents Approach ............................................................................................................6 25-year forecast of timber availability ..................................................................7 Results ...............................................................................................................8 Results for the Highland Council Area ...................................................................9 -

Shellfish Reefs at Risk

SHELLFISH REEFS AT RISK A Global Analysis of Problems and Solutions Michael W. Beck, Robert D. Brumbaugh, Laura Airoldi, Alvar Carranza, Loren D. Coen, Christine Crawford, Omar Defeo, Graham J. Edgar, Boze Hancock, Matthew Kay, Hunter Lenihan, Mark W. Luckenbach, Caitlyn L. Toropova, Guofan Zhang CONTENTS Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Methods .................................................................................................................................... 10 Results ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Condition of Oyster Reefs Globally Across Bays and Ecoregions ............ 14 Regional Summaries of the Condition of Shellfish Reefs ............................ 15 Overview of Threats and Causes of Decline ................................................................ 28 Recommendations for Conservation, Restoration and Management ................ 30 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................ 36 References .............................................................................................................................