Dutch Face-Ism. Portrait Photography and Völkisch Nationalism in the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kopstukken Van De Nsb

KOPSTUKKEN VAN DE NSB Marcel Bergen & Irma Clement Marcel Bergen & Irma Clement KOPSTUKKEN VAN DE NSB UITGEVERIJ MOKUMBOOKS Inhoud Inleiding 4 Nationaalsocialisme en fascisme in Nederland 6 De NSB 11 Anton Mussert 15 Kees van Geelkerken 64 Meinoud Rost van Tonningen 98 Henk Feldmeijer 116 Max Blokzijl 132 Robert van Genechten 155 Johan Carp 175 Arie Zondervan 184 Tobie Goedewaagen 198 Henk Woudenberg 210 Evert Roskam 222 Noten 234 Literatuur 236 Colofon 238 dwang te overtuigen van de Groot-Germaanse gedachte. Het gevolg is dat Mussert zich met enkele getrouwen terug- trekt op het hoofdkwartier aan de Maliebaan in Utrecht en de toenemende druk probeert te pareren met notities, toespraken en concessies. Naarmate de bezetting voortduurt nemen de concessies die Mussert aan de Duitse bezetter doet toe. Inleiding De Nationaal Socialistische Beweging (NSB) speelt tijdens Het Rijkscommissariaat de Tweede Wereldoorlog een opmerkelijke rol. Op 14 mei 1940 aanvaardt Arthur Seyss-Inquart in de De NSB, die op 14 december 1931 in Utrecht is opgericht in Ridderzaal de functie van Rijkscommissaris voor de een zaaltje van de Christelijke Jongenmannen Vereeniging, bezette Nederlandse gebieden. Het Rijkscommissariaat vecht tijdens haar bestaan een richtingenstrijd uit. Een strijd is een civiel bestuursorgaan en bestaat verder uit: die gaat tussen de Groot-Nederlandse gedachte, die streeft – Friederich Wimmer (commissaris-generaal voor be- naar een onafhankelijk Groot Nederland binnen een Duits stuur en justitie en plaatsvervanger van Seyss-Inquart). Rijk en de Groot-Germaanse gedachte,waarin Nederland – Hans Fischböck (generaal-commissaris voor Financiën volledig opgaat in een Groot-Germaans Rijk. Niet alleen de en Economische Zaken). richtingenstrijd maakt de NSB politiek vleugellam. -

COMPENDIUM 2021 Stichting Werkgroep Herkenning

Werkgroep Herkenning COMPENDIUM 1981 – 2021 ERVARINGEN VAN KINDEREN EN KLEINKINDEREN VAN ‘FOUTE OUDERS’ Gonda Scheffel-Baars Cuny Holthuis-Buve Paul Mantel Teun van der Vaart Een uitgave van de Stichting Werkgroep Herkenning Derde druk © 2021 Stichting Werkgroep Herkenning Vestigingsadres: Grotekreek 28 8032 JD Zwolle Postadres: Rijksstraatweg 193 1115 AR Duivendrecht Kamer van Koophandel: 41131339 ING BANK: NL24 INGB 0005 2857 97 Mobiel: +31 (0)6 330 57 003 E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://www.werkgroepherkenning.nl/ Voor actuele contactgegevens raadpleeg altijd de website: https://www.werkgroepherkenning.nl/ © Stichting Werkgroep Herkenning INHOUD Inleiding 6 0.1 Opzet van het compendium 0.2 Terminologie 0.3 Bronnenmateriaal DEEL I Hoofdstuk 1 Historische achtergronden 10 1.1 Inleiding/vooraf 1.2 De NSB in de jaren ’30 1.3 Mei 1940 en de beginjaren van de Duitse bezetting: de Nieuwe Orde 1.4 Nationaal-socialistische nevenorganisaties van de NSB: 1.4.1 De NSVO (Nat. Soc. Vrouwen Organisatie) 1.4.2 De Nationale Jeugdstorm 1.4.3 Nat. Soc. ‘fronten’ en ‘gilden’ 1.4.4 De WA (Weer Afdeling) 1.4.5 De SS 1. Nederlandse of Germaanse SS 2. Nederlandse vrijwilligers in de Waffen SS aan het Oostfront 3. Standarte ‘Westland’ 4. Standarte ‘Nordwest’ 5. Het Nederlandse Vrijwilligerslegioen 6. De Landstorm 1.4.6 De Landwacht 1.5 Dolle Dinsdag en daarna 1.6 Winter ’44 en voorjaar ’45 1.7 De arrestaties Hoofdstuk 2 Stichting Werkgroep Herkenning 31 2.1 Doelstellingen 2.2 Definiëring van de doelgroep 2.3 (Leeftijds)categorieën -

![Qui Était August Sander? [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7735/qui-%C3%A9tait-august-sander-1-507735.webp)

Qui Était August Sander? [1]

Sur les traces d’August Sander Par Bernard Birsinger propos recueillis par Emmanuel Bigler Résumé Bernard Birsinger nous raconte comment il est allé un jour au pays d’August Sander pour voir les lieux où le célèbre portraitiste a vécu et travaillé, en particulier là où il a photographié des paysages. Dans ce voyage, Bernard Birsinger a rencontré des témoins ayant connu August Sander, et il en a rapporté un travail photographique sur les lieux de mémoire de l’auteur des « Hommes du vingtième siècle ». Introduction - Qui était August Sander? [1] FIGURE 1 – August Sander en 1925 1 Bernard Birsinger (BBB [2]) : Dans toute quête culturelle, il est important de connaître le décor et aussi ce qui se cache derrière ce décor. Les biographies officielles à propos de Sander comme celle du Getty Museum [3], du MoMA[4], d’Aperture[5] ou de la Tate Gallery [6] de Londres suffisent-elles à nous renseigner ? Eh non. En plus, en tant que photographe, j’ai toujours encore en tête, de façon lancinante, cette phrase de la célèbre photographe américaine Diane Arbus [7] : « Rien n’est jamais comme on a dit que c’était, c’est ce que je n’ai jamais vu avant que je reconnais », phrase tirée de son livre paru en 1973 aux éditions du Chêne [8]. Et vous ne le saviez pas, ça alors? Il était donc grand temps pour moi de prendre mon bâton de pèlerin et de parcourir par monts et vaux l’Allemagne sur les traces de Sander, pour mener un double projet photographique. En un : mener un « Rephotographic Survey Project » comme celui mené à propos de Timothy O’Sullivan en 1977 [9], aux USA. -

Vraaggesprek Met Dick Kampman Over Zijn Onderzoek Naar

Vraaggesprek met Dick Kampman over zijn onderzoek naar stereotypering van de NSB en hoe dat kon blijven bestaan Introductie tot: ‘Kritische beschouwing over collaboratie’ (2011) en het nog uit te komen ‘Stereotypering van NSB en NSB’ers’ (2015) door J.L.M. Ebberink november 2014 1 ISBN 978-90-73947-00-9 NUR trefwoorden: sociologie, geschiedenis Uitgeverij Informatie Dokumentatie Algemeen Groningen, 2014 http://www. uitgeverida.nl Uitgegeven naar aanleiding van de bijeenkomst van de Werkgroep Herkenning op 20 november 2014 2 Voorwoord De bedoeling van dit geschriftje is een introductie te geven op de twee wetenschappelijke uitgaven van Dick Kampman: Kritische beschouwingen over collaboratie: stereotypering van de NSB (2011) en het vervolg erop, dat binnenkort uitkomt. Deze studies zijn door hun taal en methode vooral voor een wetenschappelijk georiënteerd publiek geschreven. Het idee kwam op om de vondsten die hij gedaan heeft tijdens zijn onderzoek naar vooroordelen en stereotypering wat breder uit te dragen. Het onderzoek zelf is eigenlijk niet samen te vatten omdat het om bewijsvoering gaat, waarbij alle overwegingen meetellen. Om het wetenschappelijk jargon zo veel mogelijk te mijden kwam het idee van een interview naar voren. Als socioloog heeft Dick Kampman onderzoek gedaan gebruik makend van wetenschappelijke methoden. Om het te lezen is wetenschappelijke voorkennis handig. De boeken zijn echter ook door leken te lezen. Maar dat vereist dan wel geduld. Dit is een poging om aan degene die nóch het geduld nóch de voorkennis hebben om zich in de boeken te verdiepen, te laten zien wat Dick Kampman beoogd heeft met zijn onderzoek en wat hij helaas heeft moeten constateren. -

The Timeless Imprint of Erna Lendvai-Dircksen's Das Deutsche

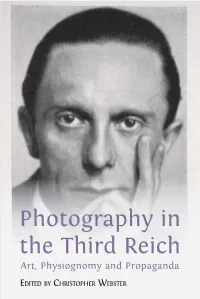

Photography in the Third Reich C Art, Physiognomy and Propaganda HRISTOPHER EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER WEBSTER This lucid and comprehensive collec� on of essays by an interna� onal group of scholars cons� tutes a photo-historical survey of select photographers who W embraced Na� onal Socialism during the Third Reich. These photographers EBSTER developed and implemented physiognomic and ethnographic photography, and, through a Selbstgleichschaltung (a self-co-ordina� on with the regime), con� nued ( to prac� ce as photographers throughout the twelve years of the Third Reich. ED .) The volume explores, through photographic reproduc� ons and accompanying analysis, diverse aspects of photography during the Third Reich, ranging from the infl uence of Modernism, the qualita� ve eff ect of propaganda photography, and the u� lisa� on of technology such as colour fi lm, to the photograph as ideological metaphor. With an emphasis on the idealised representa� on of the German body and the role of physiognomy within this representa� on, the book examines how select photographers created and developed a visual myth of the ‘master race’ and its an� theses under the auspices of the Na� onalist Socialist state. P HOTOGRAPHY Photography in the Third Reich approaches its historical source photographs as material culture, examining their produc� on, construc� on and prolifera� on. This detailed and informa� ve text will be a valuable resource not only to historians studying the Third Reich, but to scholars and students of fi lm, history of art, poli� cs, media studies, cultural studies and holocaust studies. IN THE As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. -

Ethnos and Mysticism in the Photographic Nexus Christopher Webster

Photography in the Third Reich C Art, Physiognomy and Propaganda HRISTOPHER EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER WEBSTER This lucid and comprehensive collec� on of essays by an interna� onal group of scholars cons� tutes a photo-historical survey of select photographers who W embraced Na� onal Socialism during the Third Reich. These photographers EBSTER developed and implemented physiognomic and ethnographic photography, and, through a Selbstgleichschaltung (a self-co-ordina� on with the regime), con� nued ( to prac� ce as photographers throughout the twelve years of the Third Reich. ED .) The volume explores, through photographic reproduc� ons and accompanying analysis, diverse aspects of photography during the Third Reich, ranging from the infl uence of Modernism, the qualita� ve eff ect of propaganda photography, and the u� lisa� on of technology such as colour fi lm, to the photograph as ideological metaphor. With an emphasis on the idealised representa� on of the German body and the role of physiognomy within this representa� on, the book examines how select photographers created and developed a visual myth of the ‘master race’ and its an� theses under the auspices of the Na� onalist Socialist state. P HOTOGRAPHY Photography in the Third Reich approaches its historical source photographs as material culture, examining their produc� on, construc� on and prolifera� on. This detailed and informa� ve text will be a valuable resource not only to historians studying the Third Reich, but to scholars and students of fi lm, history of art, poli� cs, media studies, cultural studies and holocaust studies. IN THE As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Reconsidering New Objectivity: Albert Renger-Patzsch and Die

RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET E. HANKEL (Under the Direction of NELL ANDREW) ABSTRACT In December of 1928, the Munich-based publisher, Kurt Wolff released a book with a new concept: a collection of one-hundred black and white photographs by Albert Renger-Patzsch. Titled Die Welt ist schön, the book presented a remarkable diversity of subjects visually unified by Renger-Patzsch’s straight-forward aesthetic. While widely praised at the time of its release, the book exists in relative obscurity today. Its legacy was cemented by the negative criticism it received in two of Walter Benjamin’s essays, “Little History of Photography” (1931) and “The Author as Producer” (1934). This paper reexamines the book in within the context of its reception, reconsidering the book’s legacy and its ties to the New Objectivity movement in Weimar. INDEX WORDS: Albert Renger-Patzsch, Die Welt ist schön, Photography, New Objectivity, Sachlichkeit, New Vision, Painting Photography Film, Walter Benjamin, Lázsló Moholy-Nagy RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET HANKEL BA, Columbia College Chicago, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2017 © 2017 Margaret E. Hankel All Rights Reserved RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET E. HANKEL Major Professor: Nell Andrew Committee: Alisa Luxenberg Janice Simon Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2017 iv DEDICATION For my mother and father v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to those who have read this work in its various stages of completion: to my advisor, Nell Andrew, whose kind and sage guidance made this project possible, to my committee members Janice Simon and Alisa Luxenberg, to Isabelle Wallace, and to my colleague, Erin McClenathan. -

August Sander Men Without Masks

HAUSER & WIRTH Press Release August Sander Men Without Masks Hauser & Wirth London 18 May – 28 July 2018 Opening: Thursday 17 May 2018, 6 – 8 pm Hauser & Wirth is delighted to present ‘August Sander. Men Without Masks’, an exhibition dedicated to the late German photographer, a forefather of conceptual art and pioneering documentarian of human diversity. Over the course of a career spanning six decades and tens of thousands of negatives, August Sander created a nuanced sociological portrait of Germany comprising images of its populace, as well as its urban settings and dramatic landscapes. Working in a rigorous fashion, he pioneered a precise, unembellished photographic aesthetic that was formative to the establishment of the medium’s independence from painting and presaged conceptual art. The artist considered empathy toward his sitters to be critical to his work, and strove not to impose a portrayal upon an unwilling subject, but to enable self-portraits. This exhibition features an extensive selection of rare large-scale Sander photographs. Made between 1910 and 1931, the portraits on view paint a picture of Germany’s complex socio-economic landscape in the years leading up to and through the Weimar Republic. These early examples of Sander’s oeuvre — in particular, the ‘Portfolio of Archetypes’, — laid the framework for ‘People of the 20th Century’, the artist’s larger, lifelong effort to catalogue contemporary German society through his photographs and to reveal the truth of its ethnic and class diversity. Upon his father’s death and on the eve of the publication of the book ‘Menschen ohne Maske’ (published in English as ‘Men Without Masks’), Sander’s son Gunther (1907 – 1987) selected and printed the HAUSER & WIRTH photographs in a unique oversize format for inclusion in an exhibition at the Mannheimer Kunstverein in 1973. -

The Holocaust, Israel and 'The Jew'

NIOD STUDIES ON WAR, HOLOCAUST, AND GENOCIDE Ensel & Gans (eds) The Holocaust, Israel and ‘the Jew’ ‘the and Israel Holocaust, The Edited by Remco Ensel and Evelien Gans The Holocaust, Israel and ‘the Jew’ Histories of Antisemitism in Postwar Dutch Society The Holocaust, Israel and ‘the Jew’ NIOD Studies on War, Holocaust, and Genocide The series encompasses peer-reviewed scholarly work on the impact of war, the Holocaust, and genocide on twentieth-century societies, covering a broad range of historical approaches in a global context, and from diverse disciplinary perspectives. Series Editors Peter Keppy, Ingrid de Zwarte, Conny Kristel and Karel Berkhoff The Holocaust, Israel and ‘the Jew’ Histories of Antisemitism in Postwar Dutch Society Edited by Remco Ensel and Evelien Gans Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Graffiti on the poster of the musical ‘Yours, Anne’ in the Valkenburger- straat – incidentally the street which in the old Jewish Quarter of Amsterdam intersects the Anne Frank Straat (photo: Thomas Schlijper / Hollandse Hoogte, 2 January 2011) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 608 4 e-isbn 978 90 4852 702 1 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462986084 nur 689 © Remco Ensel & Evelien Gans / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Dutch Face-Ism. Portrait Photography and Völkisch Nationalism in the Netherlands

Fascism 2 (2013) 18–40 brill.com/fasc Dutch Face-ism. Portrait Photography and Völkisch Nationalism in the Netherlands Remco Ensel NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies Herengracht 380, 1016 CJ Amsterdam, The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract This article takes its cue from an essay by Gerhard Richter on Walter Benjamin and the fascist aestheticization of politics. It examines the portrait photography of Dutch photographer W.F. Van Heemskerck Düker, who was a true believer in the ideology of a Greater Germany. He published a number of illustrated books on the Dutch Heimat and worked together with German photographers Erna Lendvai-Dircksen and Erich Retzlaff. When considering what type of photography was best suited to capture the photographic aesthetics of the fascist nation, the article argues that within the paradigm of the Greater German Heimat we find not so much a form of anthropometric photography, as exemplified by the work of Hans F.K. Günther, as a genre of Heimat portraits that was better equipped to satisfy the need to unify two crucial structural oppositions in fascist ideology, namely mass versus individuality, and physical appearance versus inner soul. Keywords fascism; fascist photography; The Netherlands; fascist culture; W.F. Van Heemskerck Düker; folklore; National-Socialism; Westforschung Introduction This article examines the portrait photography of Dutch photographer W.F. Van Heemskerck Düker and addresses the meaning of the portrait in fas- cist visual culture. Van Heemskerck Düker started in the 1930s as an aspiring but unknown photographer. His great opportunity came during the first years of the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, when he succeeded in becoming the head of the Photo and Film Department of the Dutch SS, and in publishing * This article was translated from Dutch by Han van der Vegt. -

Anton Musserts Verzekeringspolis Voor Nederland

Anton Musserts verzekeringspolis voor Nederland De collaboratie van de Nationaal Socialistische Beweging vergeleken met die van partijen in de ‘Germaanse’ landen in Noordwest-Europa, 1940-1945. Eduard van den Berg S1253336 Master-afstudeerscriptie Docent: Dr. B.E. van der Boom Studierichting: geschiedenis Specialisatie: Political Culture & National Identities Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen Universiteit Leiden 11 Mei 2017 Inhoudsopgave Inleiding………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Hoofdstuk 1: de ideologische ontwikkeling en machtspositie van de NS, de DNSAP en het VNV voor de oorlog…………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 Hoofdstuk 2: de ideologische ontwikkeling en machtspositie van de NSB, 1931-1940………. 15 Hoofdstuk 3: de NS, de DNSAP en het VNV tijdens de bezettingsjaren, 1940-1945………….. 28 Hoofdstuk 4: Mussert en zijn machtsstrijd, 1940-1945………………………………………………………. 44 Conclusie…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 63 Literatuurlijst………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………66 2 Inleiding ‘De NSB had tot roeping de verzekeringspolis te zijn voor het Nederlandsche volk in geval van een overwinning van Hitler. Zonder NSB zouden wij ongetwijfeld worden ingelijfd.’1 Met deze naoorlogse woorden vatte Anton Mussert samen waarom de Nationaal Socialistische Beweging zich had ingelaten met de bezetter in de jaren 1940-1945. Dit had alles te maken met zijn doel: een onafhankelijk, nationaalsocialistisch Nederland met hem als regeringsleider. Dit doel was niet uniek, het had overeenkomsten met dat van collaboratiepartijen