August Sander's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Qui Était August Sander? [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7735/qui-%C3%A9tait-august-sander-1-507735.webp)

Qui Était August Sander? [1]

Sur les traces d’August Sander Par Bernard Birsinger propos recueillis par Emmanuel Bigler Résumé Bernard Birsinger nous raconte comment il est allé un jour au pays d’August Sander pour voir les lieux où le célèbre portraitiste a vécu et travaillé, en particulier là où il a photographié des paysages. Dans ce voyage, Bernard Birsinger a rencontré des témoins ayant connu August Sander, et il en a rapporté un travail photographique sur les lieux de mémoire de l’auteur des « Hommes du vingtième siècle ». Introduction - Qui était August Sander? [1] FIGURE 1 – August Sander en 1925 1 Bernard Birsinger (BBB [2]) : Dans toute quête culturelle, il est important de connaître le décor et aussi ce qui se cache derrière ce décor. Les biographies officielles à propos de Sander comme celle du Getty Museum [3], du MoMA[4], d’Aperture[5] ou de la Tate Gallery [6] de Londres suffisent-elles à nous renseigner ? Eh non. En plus, en tant que photographe, j’ai toujours encore en tête, de façon lancinante, cette phrase de la célèbre photographe américaine Diane Arbus [7] : « Rien n’est jamais comme on a dit que c’était, c’est ce que je n’ai jamais vu avant que je reconnais », phrase tirée de son livre paru en 1973 aux éditions du Chêne [8]. Et vous ne le saviez pas, ça alors? Il était donc grand temps pour moi de prendre mon bâton de pèlerin et de parcourir par monts et vaux l’Allemagne sur les traces de Sander, pour mener un double projet photographique. En un : mener un « Rephotographic Survey Project » comme celui mené à propos de Timothy O’Sullivan en 1977 [9], aux USA. -

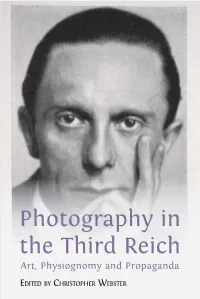

The Timeless Imprint of Erna Lendvai-Dircksen's Das Deutsche

Photography in the Third Reich C Art, Physiognomy and Propaganda HRISTOPHER EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER WEBSTER This lucid and comprehensive collec� on of essays by an interna� onal group of scholars cons� tutes a photo-historical survey of select photographers who W embraced Na� onal Socialism during the Third Reich. These photographers EBSTER developed and implemented physiognomic and ethnographic photography, and, through a Selbstgleichschaltung (a self-co-ordina� on with the regime), con� nued ( to prac� ce as photographers throughout the twelve years of the Third Reich. ED .) The volume explores, through photographic reproduc� ons and accompanying analysis, diverse aspects of photography during the Third Reich, ranging from the infl uence of Modernism, the qualita� ve eff ect of propaganda photography, and the u� lisa� on of technology such as colour fi lm, to the photograph as ideological metaphor. With an emphasis on the idealised representa� on of the German body and the role of physiognomy within this representa� on, the book examines how select photographers created and developed a visual myth of the ‘master race’ and its an� theses under the auspices of the Na� onalist Socialist state. P HOTOGRAPHY Photography in the Third Reich approaches its historical source photographs as material culture, examining their produc� on, construc� on and prolifera� on. This detailed and informa� ve text will be a valuable resource not only to historians studying the Third Reich, but to scholars and students of fi lm, history of art, poli� cs, media studies, cultural studies and holocaust studies. IN THE As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Reconsidering New Objectivity: Albert Renger-Patzsch and Die

RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET E. HANKEL (Under the Direction of NELL ANDREW) ABSTRACT In December of 1928, the Munich-based publisher, Kurt Wolff released a book with a new concept: a collection of one-hundred black and white photographs by Albert Renger-Patzsch. Titled Die Welt ist schön, the book presented a remarkable diversity of subjects visually unified by Renger-Patzsch’s straight-forward aesthetic. While widely praised at the time of its release, the book exists in relative obscurity today. Its legacy was cemented by the negative criticism it received in two of Walter Benjamin’s essays, “Little History of Photography” (1931) and “The Author as Producer” (1934). This paper reexamines the book in within the context of its reception, reconsidering the book’s legacy and its ties to the New Objectivity movement in Weimar. INDEX WORDS: Albert Renger-Patzsch, Die Welt ist schön, Photography, New Objectivity, Sachlichkeit, New Vision, Painting Photography Film, Walter Benjamin, Lázsló Moholy-Nagy RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET HANKEL BA, Columbia College Chicago, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2017 © 2017 Margaret E. Hankel All Rights Reserved RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET E. HANKEL Major Professor: Nell Andrew Committee: Alisa Luxenberg Janice Simon Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2017 iv DEDICATION For my mother and father v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to those who have read this work in its various stages of completion: to my advisor, Nell Andrew, whose kind and sage guidance made this project possible, to my committee members Janice Simon and Alisa Luxenberg, to Isabelle Wallace, and to my colleague, Erin McClenathan. -

August Sander Men Without Masks

HAUSER & WIRTH Press Release August Sander Men Without Masks Hauser & Wirth London 18 May – 28 July 2018 Opening: Thursday 17 May 2018, 6 – 8 pm Hauser & Wirth is delighted to present ‘August Sander. Men Without Masks’, an exhibition dedicated to the late German photographer, a forefather of conceptual art and pioneering documentarian of human diversity. Over the course of a career spanning six decades and tens of thousands of negatives, August Sander created a nuanced sociological portrait of Germany comprising images of its populace, as well as its urban settings and dramatic landscapes. Working in a rigorous fashion, he pioneered a precise, unembellished photographic aesthetic that was formative to the establishment of the medium’s independence from painting and presaged conceptual art. The artist considered empathy toward his sitters to be critical to his work, and strove not to impose a portrayal upon an unwilling subject, but to enable self-portraits. This exhibition features an extensive selection of rare large-scale Sander photographs. Made between 1910 and 1931, the portraits on view paint a picture of Germany’s complex socio-economic landscape in the years leading up to and through the Weimar Republic. These early examples of Sander’s oeuvre — in particular, the ‘Portfolio of Archetypes’, — laid the framework for ‘People of the 20th Century’, the artist’s larger, lifelong effort to catalogue contemporary German society through his photographs and to reveal the truth of its ethnic and class diversity. Upon his father’s death and on the eve of the publication of the book ‘Menschen ohne Maske’ (published in English as ‘Men Without Masks’), Sander’s son Gunther (1907 – 1987) selected and printed the HAUSER & WIRTH photographs in a unique oversize format for inclusion in an exhibition at the Mannheimer Kunstverein in 1973. -

FEROZ Galerie: August Sander at Paris Photo

FEROZ Galerie 28 August 2013 PRESS RELEASE FEROZ Galerie: August Sander at Paris Photo FEROZ Galerie is pleased to announce the presentation of an extraordinarily rare vintage print by Master Photographer August Sander at Paris Photo. Since it’s conception eighty-five years ago, the confident gaze of the Konditormeister has captured the fascination of viewers and continues to be one of the most sought after photographs made by August Sander. This portrait was created shortly after Sander’s highly acclaimed exhibition at the Kölnischer Kunstverein in 1927, a preview of his project, People of the 20th Century. The subject of this renowned picture is Franz Bremer, a pastry chef and the owner of the Conditorei, a popular café in the Lindenthal neighborhood of Cologne. Situated on Dürener Strasse, it was very near to Sander’s Photographic Studio and the artist was known to be a frequent visitor for coffee and cakes. Sander included the Konditor as plate number 16 in the final selection for his book, Antlitz der Zeit, (Face of Our Time) published in 1929. The artist spent six months organizing his presentation and layout, further developing the vision of his project, People of the 20th Century, and establishing a new modern format for photography books. Antlitz der Zeit was also to serve as the introductory volume, and invitation to subscribe to the larger body of work envisioned by Sander. Later in a letter to a friend Sander wrote, “Photography is like a mosaic, which only achieves a synthesis when you can display it all at once as I did in my work Antlitz der Zeit.” Equally rare to the singularity of this photograph is the exceptional state of the artist portfolio presentation mount. -

August Sander PHOTOGRAPHS from 'PEOPLE of the 20TH

August Sander PHOTOGRAPHS FROM ‘PEOPLE OF THE 20TH CENTURY’ August Sander (Herdorf, 1876 – Cologne, 1964) occupies an absolutely exemplary position in the history of pho tography. In addition, his most extensive project, People of the 20th Century, reflects the types of occupations in Germany between the Weimar Republic and the 1950s. 23.03 – 23.06.2019 Held in collaboration with the August Sander Archiv be longing to Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur in Cologne, Photographs from “People of the 20th Century” constitutes the most comprehensive exhibition ever staged in Spain on August Sander’s project of the same name. In addition to the 187 photographs organised follow ing Sander’s own typological concept, a group of motifs of the series “Studies – The Human Being” is included, that has rarely been presented in the international museum’s context until today. These pictures are dedicated to details of some of his models’ gestures, looks and postures and especially to hands. The exhibition, that shows high quality modern prints on the base of the original gelatin silver negative glass plates, is completed with a documentary section showing handwritten letters from the photographer, the portfolios made at the time for some sections and a variety of bibliographical material. August Sander (Herdorf, 1876 – Cologne, 1964) occupies an absolutely tutelary position in the history of photo graphy. From Walter Benjamin to Susan Sontag, from Roland Barthes to John Berger, a significant part of the great narrators of images measured their theoretical ap paratus before Sander’s unsentimental—and therefore politically incisive—photographs with estimation. Menschen des 20. -

Michael Jennings Sou9ce

!"#$%&'(&#)*+,-.&/(#0*+1-.+(2)+3$#(2+45+(2)+624(478//10+$-+(2)+91()+:)$;1#+<)=&>'$% !&(24#?/@A+B$%21)'+C)--$-"/ D4&#%)A+E%(4>)#*+F4'G+HI+?D&;;)#*+JKKK@*+==G+JI7LM 6&>'$/2).+>0A+N2)+B,N+6#)// D(1>')+O<9A+http://www.jstor.org/stable/779156 !%%)//).A+PQRPPRJKKQ+KSAIK Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org Agriculture, Industry, and the Birth of the Photo-Essayin the Late Weimar Republic MICHAEL JENNINGS Amongthe mostsinister phenomena in intellectualhistory is the avoidance of the concrete... -

Diane Arbus Born 1923 in New York

This document was updated March 4, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Diane Arbus Born 1923 in New York. Died 1971 in New York. EDUCATION 1955-1957 Studied photography with Lisette Model, New York 1928-1940 Ethical Culture Fieldston School, New York SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Diane Arbus: Photographs, 1956-1971, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, February 22 – May 17, 2020 2019 Our Lady of the Flowers: Diane Arbus | Carol Rama, Lévy Gorvy, Hong Kong, September 26 – November 16, 2019 [two-person exhibition] 2018 Diane Arbus Untitled, David Zwirner, New York, November 2 – December 15, 2018 Diane Arbus: A box of 10 photographs, Smithsonian American Art Museum, April 6, 2018 – January 27, 2019 [catalogue] 2017 Diane Arbus: In the Park, Lévy Gorvy, New York, May 2 – June 28, 2017 2016-2019 diane arbus: in the beginning, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, July 12 – November 27, 2016 [itinerary: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, January 21 – April 30, 2017; Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires Malba, Buenos Aires, July 14 – October 9, 2017; Hayward Gallery, London, February 13 – May 6, 2019] [catalogue] 2016-2018 Diane Arbus: American portraits, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, June 6 – October 30, 2016 [itinerary: Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery, Booragul, Australia, July 9 – August 20, 2017; Heide Museum of Modern Art, Bulleen, Australia, March 17 – June 17, 2018; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, July 16 – September -

GM Texte (Sprueth Magers)

Press coverage Sprüth Magers Water tower, Crailsheim, Germany, 1980 Press coverage Sprüth Magers Hilla Becher in conversation with Thomas Weaver Düsseldorf in an early February morning in 2013 was shrouded in thick fog and the ground covered in a light dusting of snow, the effect of which was to render the city almost totally devoid of colour – perfect conditions, perhaps, for meeting a photographer who famously works only in black and white. Born in 1934, Hilla Becher moved to Düsseldorf in 1957, then as Hilla Wobeser, having survived all manner of wartime traumas and forced from her childhood home in Potsdam first to Pomerania, and then to Prenzlau, Rostock, Potsdam again, Berlin and finally Hamburg. One year after arriving in the city, while working as a photographer in an advertising agency, she met an interesting man named Bernd Becher, who she married three years later (despite a certain degree of suspicion as to why anyone would want to get married). Over the next half century the two of them – soon referred to by the collective moniker ‘The Bechers’ – transformed not only the way buildings could be photographed, but also the ascribed values attached to those buildings. The basic template of a typical Becher photograph is first the identification of an industrial or vernacular structure – for example, a blast-furnace, lime kiln, water tower, gasometer or grain elevator – and then its capture on film via a large plate-camera in weather and seasonal conditions that would facilitate the clearest depiction of its subject matter. The idea was to show the whole thing in its entirety, and nothing else. -

August Sander's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer August Sander’s ‘Der Bauer’ and the Pervasiveness of the Peasant Tradition Citation for published version: Weikop, C 2013, 'August Sander’s ‘Der Bauer’ and the Pervasiveness of the Peasant Tradition' Tate Papers, vol 19, no. Spring 2013, 5. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Tate Papers Publisher Rights Statement: © Weikop, C. (2013). August Sander’s ‘Der Bauer’ and the Pervasiveness of the Peasant Tradition. Tate Papers, 19(Spring 2013), [5]. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Apr. 2017 August Sander ’s Der Bauer and the Pervasiveness of the Peasant Tradition | Tate Page 1 of 15 Research publications Research Research publications Tate papers RESEARCH ARTICLES August Sander’s Der Bauer and the Pervasiveness of the Peasant Tradition By Christian Weikop 20 March 2013 Tate Papers Issue 19 Examining August Sander’s Der Bauer group of photographs in relation to the historical representation of peasants in German art, Christian Weikop draws distinctions between Sander’s interest in peasant types and the ideological agendas of National Socialist proponents of racial purity. -

August Sander

HAUSER & WIRTH Press Release August Sander Hauser & Wirth New York, 69th Street 20 April – 17 June 2017 Opening reception: Thursday 20 April, 6 – 8 pm ‘I hate nothing more than sugary photographs with tricks, poses and effects. So allow me to be honest and tell the truth about our age and its people.’ – August Sander New York… Beginning 20 April 2017, Hauser & Wirth will present ‘August Sander’, the gallery’s first exhibition devoted to the late German photographer, a forefather of conceptual art and pioneering documentarian of human diversity. The exhibition features 40 rare large-scale Sander photographs, which have come directly from The August Sander Family Collection. Made between 1910 and 1931, the portraits on view paint a picture of Germany’s complex socioeconomic landscape in the years leading up to and through the Weimar Republic. These early examples of Sander’s oeuvre — in particular, the ‘Portfolio of Archetypes’, 12 images at the heart of Hauser & Wirth’s presentation — laid the framework for ‘People of the 20th Century’, the artist’s larger, lifelong effort to catalogue contemporary German society through his photographs and to reveal the truth of its ethnic and class diversity. Sander’s son Gunther (1907 — 1987) selected and printed these 40 photographs, along with 90 others, in a unique oversize format in 1972 for inclusion in the exhibition ‘Men without Masks: Faces of Germany 1910 — 1938’ at the Mannheimer Kunstverein in 1973. With stunning detail drawn forth by their scale, these ‘Men without Masks’ photographs capture a critical moment in Sander’s artistic evolution and in our collective history.