Michael Jennings Sou9ce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visions of a Technological Future

Visions of a Technological Future: Experience and Expectation of Progress in the Interwar United States Antti Alanko University of Jyväskylä Department of History and Ethnology General History Master’s Thesis JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Historian ja etnologian laitos Tekijä – Author Antti Mikael Alanko Työn nimi – Title Visions of a Technological Future: Experience and Expectation of Progress in the Interwar United States Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Yleinen historia Pro gradu -tutkielma Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages Kesäkuu 2015 129 Tiivistelmä – Abstract Tarkastelen tutkielmassa maailmansotien välisenä aikana Yhdysvaltalaisissa tiede- ja tekniikkajulkaisuissa Popular Mechanicsissa ja Popular Science Monthlyssa esiintynyttä tulevaisuusajattelua. Tutkielman tarkoituksena on selvittää mitä tulevaisuudesta maailmansotien välisenä aikana Yhdysvalloissa ajateltiin. Erityisesti tarkastelen mitä edellä mainituissa aikakauslehdissä kirjoitettiin kaupungin, rakentamisen ja kodin tulevaisuudesta. Käsittelen aineistoa pääosin historiallisen kuvatutkimuksen keinoin. Tutkimuksen teoreettinen viitekehys pohjaa Reinhart Koselleckin historiallisten aikojen teoriaan, erityisesti kokemustilan ja odotushorisontin väliseen suhteeseen. Tämän tutkielman hypoteesi on, että kirjoittajien optimistiset tulevaisuudenodotukset syntyivät 1800- luvun lopun ja 1900-luvun alun hyvin nopean ja kiihtyvän teknologisen kehityksen seurauksena. Tämä teknologisen kehityksen kokemus tuotti -

The Syntheist Movement and Creating God in the Internet Age

1 I Sing the Body Electric: The Syntheist Movement and Creating God in the Internet Age Melodi H. Dincer Senior Thesis Brown University Department of Religious Studies Adviser: Paul Nahme Second Reader: Daniel Vaca Providence, Rhode Island April 15, 20 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments. 3 Introduction: Making the Internet Holy. .4 Chapter (1) A Technophilic Genealogy: Piracy and Syntheism as Cybernetic Offspring. .12 Chapter (2) The Atheist Theology of Syntheism . 49 Chapter (3) Enacted Syntheisms: An Ethics of Active Virtuality and Virtual Activity. 96 (In)Conclusions. 138 Works Cited. 144 3 Acknowledgments I would briefly like to thank anyone who has had a hand—actually, even the slightest brush of a finger in making this project materialize outside of the confines of my own brain matter. I would first like to thank Kerri Heffernan and my Royce Fellowship cohort for supporting my initial research on the Church of Kopimism. My time in Berlin and Stockholm on behalf of the Royce made an indelible mark on my entire academic career thus far, without which this thesis would definitely not be as out-of-the-box as it is proud to be. I would also like to thank a few professors in the Religious Studies department who, whether they were aware of it or not, encouraged my confidence in this area of study and shaped how I approached the religious communities this project concerns. Specifically, thank you to Prof. Denzey-Lewis, who taught my first religious studies course at Brown and graciously sponsored my Royce research amidst her own travels. Also, infinite thanks and blessings to Fannie Bialek, who so deftly modeled all that is good in this discipline, and all that is most noble in the often confusing, frustrating, and stressful task of teaching “hard” topics. -

“We Need a Showing of All Hands”: Technological Utopianism in <Em>

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Faculty Publications 2011 “We Need a Showing of All Hands”: Technological Utopianism in MAKE Magazine Susan Currie Sivek Linfield College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/mscmfac_pubs Part of the Journalism Studies Commons DigitalCommons@Linfield Citation Sivek, Susan Currie, "“We Need a Showing of All Hands”: Technological Utopianism in MAKE Magazine" (2011). Faculty Publications. Accepted Version. Submission 5. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/mscmfac_pubs/5 This Accepted Version is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Accepted Version must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Running head: MAKE MAGAZINE “We Need a Showing of All Hands”: Technological Utopianism in MAKE Magazine Keywords: magazine journalism, ideology, textual analysis, technological utopianism MAKE MAGAZINE 2 Make magazine is one of a growing genre of magazines that provides practical information to readers on ways to improve their homes and communities while also connecting their projects to greater social and environmental goals. The magazine and its associated event, -

“A Way of Revealing”: Technology and Utopianism in Contemporary Culture

“A Way of Revealing”: 58 Technology and Utopianism in Contemporary Culture s Alex Hall e i d u t S y g Abstract o cultural production platforms (e.g., the Internet l o n Although technology was once viewed liter- and film technologies). If the hermeneutic h c e ally as a means of bringing about utopian socie- employed by subscribers to the philosophy of T f ty, its means to that end was exhausted in the Ernst Bloch is accepted, then utopian potential o l a minds of many when it fostered the nuclear can be found in any cultural product. Since most n r u attacks on Japan in 1945. Since then, not only cultural production is dependent upon technolo- o J has technology lost its utopian verve, but it also gy in one way or another, then it hardly seems a e h T has been viewed by some quite pessimistically. stretch to grant technology some credit in the Nevertheless, technology does provide an area of utopian potential, despite what it leaves avenue for utopian cultural production, whose to be desired in others. Still, the history of tech- utopian energy must often be rescued by readers nology’s relationship with utopianism is quite and scholars using the Blochian utopian complicated, especially with regard to technolo- hermeneutic. In this way technology is as gy as a means to a socially utopian end. Heidegger described it—“a way of revealing,” that is, the tool that brings the carving out from Enlightenment thinkers saw technology as within the rock. This article argues that although one of several means of bringing about a perfect technology has come to be viewed by some pes- world, but they also recognized its inherent neg- simistically in the years since Hiroshima and ative possibilities. -

![Qui Était August Sander? [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7735/qui-%C3%A9tait-august-sander-1-507735.webp)

Qui Était August Sander? [1]

Sur les traces d’August Sander Par Bernard Birsinger propos recueillis par Emmanuel Bigler Résumé Bernard Birsinger nous raconte comment il est allé un jour au pays d’August Sander pour voir les lieux où le célèbre portraitiste a vécu et travaillé, en particulier là où il a photographié des paysages. Dans ce voyage, Bernard Birsinger a rencontré des témoins ayant connu August Sander, et il en a rapporté un travail photographique sur les lieux de mémoire de l’auteur des « Hommes du vingtième siècle ». Introduction - Qui était August Sander? [1] FIGURE 1 – August Sander en 1925 1 Bernard Birsinger (BBB [2]) : Dans toute quête culturelle, il est important de connaître le décor et aussi ce qui se cache derrière ce décor. Les biographies officielles à propos de Sander comme celle du Getty Museum [3], du MoMA[4], d’Aperture[5] ou de la Tate Gallery [6] de Londres suffisent-elles à nous renseigner ? Eh non. En plus, en tant que photographe, j’ai toujours encore en tête, de façon lancinante, cette phrase de la célèbre photographe américaine Diane Arbus [7] : « Rien n’est jamais comme on a dit que c’était, c’est ce que je n’ai jamais vu avant que je reconnais », phrase tirée de son livre paru en 1973 aux éditions du Chêne [8]. Et vous ne le saviez pas, ça alors? Il était donc grand temps pour moi de prendre mon bâton de pèlerin et de parcourir par monts et vaux l’Allemagne sur les traces de Sander, pour mener un double projet photographique. En un : mener un « Rephotographic Survey Project » comme celui mené à propos de Timothy O’Sullivan en 1977 [9], aux USA. -

Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy

A Dissertation entitled “Keep Your Dirty Lights On:” Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy Exceptionalism in American Society by Daniel A. French Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History _________________________________________ Dr. Diane F. Britton, Committee Chairperson _________________________________________ Dr. Peter Linebaugh, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Daryl Moorhead, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Kim E. Nielsen, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Patricia Komuniecki Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2014 Copyright 2014, Daniel A. French This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the express permission of the author. An Abstract of “Keep Your Dirty Lights On:” Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy Exceptionalism in American Society by Daniel A. French Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History The University of Toledo December 2014 Electricity has been defined by American society as a modern and clean form of energy since it came into practical use at the end of the nineteenth century, yet no comprehensive study exists which examines the roots of these definitions. This dissertation considers the social meanings of electricity as an energy technology that became adopted between the mid- nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth centuries. Arguing that both technical and cultural factors played a role, this study shows how electricity became an abstracted form of energy in the minds of Americans. As technological advancements allowed for an increasing physical distance between power generation and power consumption, the commodity of electricity became consciously detached from the steam and coal that produced it. -

The Timeless Imprint of Erna Lendvai-Dircksen's Das Deutsche

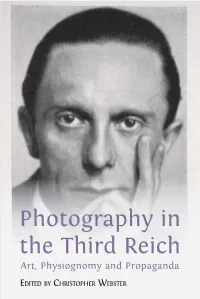

Photography in the Third Reich C Art, Physiognomy and Propaganda HRISTOPHER EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER WEBSTER This lucid and comprehensive collec� on of essays by an interna� onal group of scholars cons� tutes a photo-historical survey of select photographers who W embraced Na� onal Socialism during the Third Reich. These photographers EBSTER developed and implemented physiognomic and ethnographic photography, and, through a Selbstgleichschaltung (a self-co-ordina� on with the regime), con� nued ( to prac� ce as photographers throughout the twelve years of the Third Reich. ED .) The volume explores, through photographic reproduc� ons and accompanying analysis, diverse aspects of photography during the Third Reich, ranging from the infl uence of Modernism, the qualita� ve eff ect of propaganda photography, and the u� lisa� on of technology such as colour fi lm, to the photograph as ideological metaphor. With an emphasis on the idealised representa� on of the German body and the role of physiognomy within this representa� on, the book examines how select photographers created and developed a visual myth of the ‘master race’ and its an� theses under the auspices of the Na� onalist Socialist state. P HOTOGRAPHY Photography in the Third Reich approaches its historical source photographs as material culture, examining their produc� on, construc� on and prolifera� on. This detailed and informa� ve text will be a valuable resource not only to historians studying the Third Reich, but to scholars and students of fi lm, history of art, poli� cs, media studies, cultural studies and holocaust studies. IN THE As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. -

The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction

16 EDWARD JAMES Utopias and anti-utopias It is sometimes said that the ability of the writer to imagine a better place in which to live died in the course of the twentieth century, extinguished by the horrors of total war, of genocide and of totalitarianism. The genre of utopia, created unwittingly by Sir Thomas More when he published Utopia in 1516, died when idealism perished, a victim to twentieth-century pessimism and cynicism. It is the contention of this chapter that utopia has not disappeared; it has merely mutated, within the field of sf, into something very different from the classic utopia. Hoda M. Zaki, whose Phoenix Renewed (1988)isthe only published monograph on sf utopias, was on the point of recognizing this, although she failed; as a political scientist, she was still looking in vain for the classic utopia. She concluded that ‘the disappearance of utopian literature in the twentieth century is surprising’ and ‘an issue with serious implications for the entire body politics’. Her study was based on the nineteen novels which had won the Nebula Award between 1965 and 1982. Almost all these novels had utopian elements, she concluded, but none of them were actual utopias: although many of those novels offered critiques of the contemporary world, none of them offered the necessary coherent account of a superior and de- sirable alternative in the future. Modern sf thus had no utopias to offer, but only ‘tantalizing fragments in the utopian tradition’.1 However, one can use the same evidence to suggest something quite different: if almost all the novels had utopian elements, this is a demonstration of the profound way in which utopianism has permeated sf. -

Automation and the Meaning of Work in the Postwar United States

The Misanthropic Sublime: Automation and the Meaning of Work in the Postwar United States Jason Resnikoff Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Jason Zachary Resnikoff All rights reserved Abstract “The Misanthropic Sublime: Automation and the Meaning of Work in the Postwar United States” Jason Resnikoff In the United States of America after World War II, Americans from across the political spectrum adopted the technological optimism of the postwar period to resolve one of the central contradictions of industrial society—the opposition between work and freedom. Although classical American liberalism held that freedom for citizens meant owning property they worked for themselves, many Americans in the postwar period believed that work had come to mean the act of maintaining mere survival. The broad acceptance of this degraded meaning of work found expression in a word coined by managers in the immediate postwar period: “automation.” Between the late 1940s and the early 1970s, the word “automation” stood for a revolutionary development, even though few could agree as to precisely what kind of technology it described. Rather than a specific technology, however, this dissertation argues that “automation” was a discourse that defined work as mere biological survival and saw the end of human labor as the the inevitable result of technological progress. In premising liberation on the end of work, those who subscribed to the automation discourse made political freedom contingent not on the distribution of power, but on escape from the limits of the human body itself. -

The Intimate World of Lyonel Feininger

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART "»• * 11 WEST 53 STRUT, NEW YORK 19. N. Y. Mond^anuary 1*, 1963 TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 PRESS PREVIEW: Monday, January Ik, I963 11 a.m. - k p.m. The Intimate World of Lyonel Feininger, an exhibition of 60 watercolors, drawings, prints and 108 toys opening at the Museum of Modern Art, Tuesday, January 15, will show a virtually unkncn aspect of the famous American artist. Known as an artist of formal achievements, Feininger is revealed in this show as a man of humor, warmth and sometimes pathos. His watercolors, drawings, prints, comic strips, toys and even letters, are peopled with creatures, real extraordinary and always human. Most of the works have been lent by the artist's widow and family and have never been shown before. The exhibition, selected by William S. Lieberman, Curator of Drawings and Prints, continues through March 12. Although hi© career was spent mostly in Germany, much of Feininger's art was inspired by memories of his childhood in New York City, where he was born in I87I and died in I956, The Second Avenue Elevated, the New York Central locomotives, the schooners, motor-sailers and steamboats in the harbor lingered long in his mind and nourished the iconography of his art. He himself wrote: "I don't paint a picture in the traditional sense. From deep within arises an almost painful urge for the realization of inner experiences, an overwhelming longir~, an unearthly nostalgia overcomes me at times to bring them to light out of the past." Such feelings for America are revealed in his thematic devotion to boats, as, seen here in some dozen compositions ranging from antique galleons to motor yachts, A similar nostalgia perhaps inspired the two comic strip serials, The Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkle's World, which he sent each week from Germany in I906 to the Chicago Sunday Tribune. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Reconsidering New Objectivity: Albert Renger-Patzsch and Die

RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET E. HANKEL (Under the Direction of NELL ANDREW) ABSTRACT In December of 1928, the Munich-based publisher, Kurt Wolff released a book with a new concept: a collection of one-hundred black and white photographs by Albert Renger-Patzsch. Titled Die Welt ist schön, the book presented a remarkable diversity of subjects visually unified by Renger-Patzsch’s straight-forward aesthetic. While widely praised at the time of its release, the book exists in relative obscurity today. Its legacy was cemented by the negative criticism it received in two of Walter Benjamin’s essays, “Little History of Photography” (1931) and “The Author as Producer” (1934). This paper reexamines the book in within the context of its reception, reconsidering the book’s legacy and its ties to the New Objectivity movement in Weimar. INDEX WORDS: Albert Renger-Patzsch, Die Welt ist schön, Photography, New Objectivity, Sachlichkeit, New Vision, Painting Photography Film, Walter Benjamin, Lázsló Moholy-Nagy RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET HANKEL BA, Columbia College Chicago, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2017 © 2017 Margaret E. Hankel All Rights Reserved RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET E. HANKEL Major Professor: Nell Andrew Committee: Alisa Luxenberg Janice Simon Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2017 iv DEDICATION For my mother and father v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to those who have read this work in its various stages of completion: to my advisor, Nell Andrew, whose kind and sage guidance made this project possible, to my committee members Janice Simon and Alisa Luxenberg, to Isabelle Wallace, and to my colleague, Erin McClenathan.