The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quasiquote #9

“9” Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the gene pool, up pops a shark, with Henry Winkler chasing after it on a motorbike. Three full years after issue eight, QUASIQUOTE 9 makes its bow in April 2012. All the usual things apply: its editor is Sandra Bond, 40 Cleveland Park Avenue, London E17 7BS; it is available by editorial fiat, except if delivered by car, when it comes in the editorial Saab; monetary subscriptions and stamps are unnecessary but accepted at a push; contributors and correspondents are encouraged to e-mail [email protected]; insurgence against fwa and fwuk is likewise encouraged; an apple a day keeps the doctor away. contents FRONT COVER: Dan Steffan p3: HEAVY IN THE AIR: Andy Porter p5: A TISSUE: Tim C. Marion p6: HOTEL PREVIA: Rob Jackson p15: EASTERCON 1978 ART PORTFOLIO p20: THE EXPLORATION OF LOGICAL PARADOXES: Robert Sheckley interviewed by Leroy Kettle p31: THE MISSED OPPORTUNITIES OF ERIC FRANK RUSSELL: Peter Weston p33: ISH MAIL: letter column p39: WATCH OUT FOR STOBOR: editorial and closing thoughts BACK COVER: D West INTERIOR ART this issue: p2, p5, Steve Stiles: p3, p33, p35,p39, William Rotsler: p14, John Toon; p32, Marc Schirmeister. HEAVY IN THE AIR by Andy Porter Last night, January 8th 2011, I was doing my usual tossing and turning while I tried to get to sleep, my mind racing in its usual rapidfire way, refusing to calm down. A gunman in Arizona shot politician Gabrielle Giffords; as well as critically wounding her, he killed six bystanders. -

Visions of a Technological Future

Visions of a Technological Future: Experience and Expectation of Progress in the Interwar United States Antti Alanko University of Jyväskylä Department of History and Ethnology General History Master’s Thesis JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Historian ja etnologian laitos Tekijä – Author Antti Mikael Alanko Työn nimi – Title Visions of a Technological Future: Experience and Expectation of Progress in the Interwar United States Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Yleinen historia Pro gradu -tutkielma Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages Kesäkuu 2015 129 Tiivistelmä – Abstract Tarkastelen tutkielmassa maailmansotien välisenä aikana Yhdysvaltalaisissa tiede- ja tekniikkajulkaisuissa Popular Mechanicsissa ja Popular Science Monthlyssa esiintynyttä tulevaisuusajattelua. Tutkielman tarkoituksena on selvittää mitä tulevaisuudesta maailmansotien välisenä aikana Yhdysvalloissa ajateltiin. Erityisesti tarkastelen mitä edellä mainituissa aikakauslehdissä kirjoitettiin kaupungin, rakentamisen ja kodin tulevaisuudesta. Käsittelen aineistoa pääosin historiallisen kuvatutkimuksen keinoin. Tutkimuksen teoreettinen viitekehys pohjaa Reinhart Koselleckin historiallisten aikojen teoriaan, erityisesti kokemustilan ja odotushorisontin väliseen suhteeseen. Tämän tutkielman hypoteesi on, että kirjoittajien optimistiset tulevaisuudenodotukset syntyivät 1800- luvun lopun ja 1900-luvun alun hyvin nopean ja kiihtyvän teknologisen kehityksen seurauksena. Tämä teknologisen kehityksen kokemus tuotti -

The Syntheist Movement and Creating God in the Internet Age

1 I Sing the Body Electric: The Syntheist Movement and Creating God in the Internet Age Melodi H. Dincer Senior Thesis Brown University Department of Religious Studies Adviser: Paul Nahme Second Reader: Daniel Vaca Providence, Rhode Island April 15, 20 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments. 3 Introduction: Making the Internet Holy. .4 Chapter (1) A Technophilic Genealogy: Piracy and Syntheism as Cybernetic Offspring. .12 Chapter (2) The Atheist Theology of Syntheism . 49 Chapter (3) Enacted Syntheisms: An Ethics of Active Virtuality and Virtual Activity. 96 (In)Conclusions. 138 Works Cited. 144 3 Acknowledgments I would briefly like to thank anyone who has had a hand—actually, even the slightest brush of a finger in making this project materialize outside of the confines of my own brain matter. I would first like to thank Kerri Heffernan and my Royce Fellowship cohort for supporting my initial research on the Church of Kopimism. My time in Berlin and Stockholm on behalf of the Royce made an indelible mark on my entire academic career thus far, without which this thesis would definitely not be as out-of-the-box as it is proud to be. I would also like to thank a few professors in the Religious Studies department who, whether they were aware of it or not, encouraged my confidence in this area of study and shaped how I approached the religious communities this project concerns. Specifically, thank you to Prof. Denzey-Lewis, who taught my first religious studies course at Brown and graciously sponsored my Royce research amidst her own travels. Also, infinite thanks and blessings to Fannie Bialek, who so deftly modeled all that is good in this discipline, and all that is most noble in the often confusing, frustrating, and stressful task of teaching “hard” topics. -

“We Need a Showing of All Hands”: Technological Utopianism in <Em>

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Faculty Publications 2011 “We Need a Showing of All Hands”: Technological Utopianism in MAKE Magazine Susan Currie Sivek Linfield College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/mscmfac_pubs Part of the Journalism Studies Commons DigitalCommons@Linfield Citation Sivek, Susan Currie, "“We Need a Showing of All Hands”: Technological Utopianism in MAKE Magazine" (2011). Faculty Publications. Accepted Version. Submission 5. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/mscmfac_pubs/5 This Accepted Version is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Accepted Version must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Running head: MAKE MAGAZINE “We Need a Showing of All Hands”: Technological Utopianism in MAKE Magazine Keywords: magazine journalism, ideology, textual analysis, technological utopianism MAKE MAGAZINE 2 Make magazine is one of a growing genre of magazines that provides practical information to readers on ways to improve their homes and communities while also connecting their projects to greater social and environmental goals. The magazine and its associated event, -

“A Way of Revealing”: Technology and Utopianism in Contemporary Culture

“A Way of Revealing”: 58 Technology and Utopianism in Contemporary Culture s Alex Hall e i d u t S y g Abstract o cultural production platforms (e.g., the Internet l o n Although technology was once viewed liter- and film technologies). If the hermeneutic h c e ally as a means of bringing about utopian socie- employed by subscribers to the philosophy of T f ty, its means to that end was exhausted in the Ernst Bloch is accepted, then utopian potential o l a minds of many when it fostered the nuclear can be found in any cultural product. Since most n r u attacks on Japan in 1945. Since then, not only cultural production is dependent upon technolo- o J has technology lost its utopian verve, but it also gy in one way or another, then it hardly seems a e h T has been viewed by some quite pessimistically. stretch to grant technology some credit in the Nevertheless, technology does provide an area of utopian potential, despite what it leaves avenue for utopian cultural production, whose to be desired in others. Still, the history of tech- utopian energy must often be rescued by readers nology’s relationship with utopianism is quite and scholars using the Blochian utopian complicated, especially with regard to technolo- hermeneutic. In this way technology is as gy as a means to a socially utopian end. Heidegger described it—“a way of revealing,” that is, the tool that brings the carving out from Enlightenment thinkers saw technology as within the rock. This article argues that although one of several means of bringing about a perfect technology has come to be viewed by some pes- world, but they also recognized its inherent neg- simistically in the years since Hiroshima and ative possibilities. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy

A Dissertation entitled “Keep Your Dirty Lights On:” Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy Exceptionalism in American Society by Daniel A. French Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History _________________________________________ Dr. Diane F. Britton, Committee Chairperson _________________________________________ Dr. Peter Linebaugh, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Daryl Moorhead, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Kim E. Nielsen, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Patricia Komuniecki Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2014 Copyright 2014, Daniel A. French This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the express permission of the author. An Abstract of “Keep Your Dirty Lights On:” Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy Exceptionalism in American Society by Daniel A. French Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History The University of Toledo December 2014 Electricity has been defined by American society as a modern and clean form of energy since it came into practical use at the end of the nineteenth century, yet no comprehensive study exists which examines the roots of these definitions. This dissertation considers the social meanings of electricity as an energy technology that became adopted between the mid- nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth centuries. Arguing that both technical and cultural factors played a role, this study shows how electricity became an abstracted form of energy in the minds of Americans. As technological advancements allowed for an increasing physical distance between power generation and power consumption, the commodity of electricity became consciously detached from the steam and coal that produced it. -

Automation and the Meaning of Work in the Postwar United States

The Misanthropic Sublime: Automation and the Meaning of Work in the Postwar United States Jason Resnikoff Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Jason Zachary Resnikoff All rights reserved Abstract “The Misanthropic Sublime: Automation and the Meaning of Work in the Postwar United States” Jason Resnikoff In the United States of America after World War II, Americans from across the political spectrum adopted the technological optimism of the postwar period to resolve one of the central contradictions of industrial society—the opposition between work and freedom. Although classical American liberalism held that freedom for citizens meant owning property they worked for themselves, many Americans in the postwar period believed that work had come to mean the act of maintaining mere survival. The broad acceptance of this degraded meaning of work found expression in a word coined by managers in the immediate postwar period: “automation.” Between the late 1940s and the early 1970s, the word “automation” stood for a revolutionary development, even though few could agree as to precisely what kind of technology it described. Rather than a specific technology, however, this dissertation argues that “automation” was a discourse that defined work as mere biological survival and saw the end of human labor as the the inevitable result of technological progress. In premising liberation on the end of work, those who subscribed to the automation discourse made political freedom contingent not on the distribution of power, but on escape from the limits of the human body itself. -

Ivan's Final Dissertation

Copyright by Ivan Angus Wolfe 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Ivan Angus Wolfe certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Arguing In Utopia: Edward Bellamy, Nineteenth Century Utopian Fiction, and American Rhetorical Culture Committee: Jeffrey Walker, Supervisor Mark Longaker Martin Kevorkian Trish Roberts-Miller Janet Davis Gregory Clark Arguing In Utopia: Edward Bellamy, Nineteenth Century Utopian Fiction, and American Rhetorical Culture by Ivan Angus Wolfe, A.A.S.; B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of English The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2009 Dedication To Alexandra Acknowledgements I would like to thank my entire dissertation committee for their invaluable feedback during every step of my writing process. Jeffrey Walker was an invaluable director, always making time for my questions and responding with feedback to my chapters in a timely manner. Martin Kevorkian, Mark Longaker, Janet Davis, and Trish Roberts-Miller all also gave excellent advice and made themselves available whenever I needed them. Gregory Clark not only provided the initial impetus for my interest in this area, but graciously joined the committee despite his numerous commitments. Most graduate students would feel blessed to have such a conscientious and careful committee. I would also like to thank my wife, Alexandra, for her help. She has likely read this dissertation more times than anyone but me. Elizabeth Cullingford also deserves special thanks for being an excellent English department chair and making me feel welcome my first semester at UT as her Teaching Assistant for E316K. -

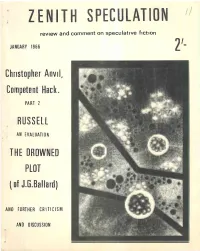

Zenith-Speculation 11 Weston

ZENITH SPECULATION ' review and comment on speculative fiction JANUARY 1966 2'- Christopher Anvil, Competent Hack. PART 2 RUSSELL A AN EVALUATION THE DROWNED PLOT (of J.G.Ballard) ANO FURTHER CRITICISM AND DISCUSSION REVIEW AND COMMENT UPON SPECULATIVE FICTION January 1966 Vcl.l, No. 11 ZENITH SPECULATION is an amateur Articles magazine containing criticism & RUSSELL 4 discussion of speculative fiction Richard Gordon It is published quarterly from THE DROWNED PLOT (of J.G.Ballard) 10 the editorial address, tn which J.P.Patrizio all articles,. artwork, comments ....ABOUT TELEPATHIST 18 on the magazine, and UK subscrip John Brunner tions should be addressed. CHRISTOPHER ANVIL, COMPETENT HACK 27 No payment can at present be made Peter R.Weston (Part 2.) for published material, but com plimentary copies will be sent to Departments contributors tn the magazine. CONTENTS & EDITORIAL 1 ZENITH will be exchanged with DOUBLE BOOKING 19 other amateur magazines, as pre (Book Reviews) arranged with the editor. Archie & Boryl Mercer THE MELTING POT 1 35 Subscriptions are 10/- for five (Letters from readers) issues, and should be sent to the editor. Single copies each 2/-, U.S. subscriptions are /1.50 for all unsigned work is by the editor five issues, and should be sent to our Agent, Albert J. Lewis,c/<. 1825 Greenfield Ave., J»os Angeles California, Single copies JO/ FRONT COVER by Joseph Zajackowski Column advertising rates; 6d for 10 words (10/). Rates for display Interior illustrations by Latto, advertisements on request. Zajackowski, & Pitt. Edited and Published by Pater R. Weston, 9 Porlock Crescent, Northfield, Birmingham, JI. -

Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Guides to Manuscript Collections Search Our Collections 2006 0749: Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006 Marshall University Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sc_finding_aids Part of the Fiction Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Playwriting Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006, Accession No. 2006/04.0749, Special Collections Department, Marshall University, Huntington, WV. This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Search Our Collections at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides to Manuscript Collections by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 0 REGISTER OF THE NELSON SLADE BOND COLLECTION Accession Number: 2006/04.749 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia 2007 1 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, WV 25755-2060 Finding Aid for the Nelson Slade Bond Collection, ca.1920-2006 Accession Number: 2006/04.749 Processor: Gabe McKee Date Completed: February 2008 Location: Special Collections Department, Morrow Library, Room 217 and Nelson Bond Room Corporate Name: N/A Date: ca.1920-2006, bulk of content: 1935-1965 Extent: 54 linear ft. System of Arrangement: File arrangement is the original order imposed by Nelson Bond with small variations noted in the finding aid. The collection was a gift from Nelson S. Bond and his family in April of 2006 with other materials forwarded in May, September, and November of 2007. -

Fifty Works of Fiction Libertarians Should Read

Liberty, Art, & Culture Vol. 30, No. 3 Spring 2012 Fifty works of fiction libertarians should read By Anders Monsen Everybody compiles lists. These usually are of the “top 10” Poul Anderson — The Star Fox (1965) kind. I started compiling a personal list of individualist titles in An oft-forgot book by the prolific and libertarian-minded the early 1990s. When author China Miéville published one Poul Anderson, a recipient of multiple awards from the Lib- entitled “Fifty Fantasy & Science Fiction Works That Social- ertarian Futurist Society. This space adventure deals with war ists Should Read” in 2001, I started the following list along and appeasement. the same lines, but a different focus. Miéville and I have in common some titles and authors, but our reasons for picking Margaret Atwood—The Handmaid’s Tale (1986) these books probably differ greatly. A dystopian tale of women being oppressed by men, while Some rules guiding me while compiling this list included: being aided by other women. This book is similar to Sinclair 1) no multiple books by the same writer; 2) the winners of the Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here or Robert Heinlein’s story “If This Prometheus Award do not automatically qualify; and, 3) there Goes On—,” about the rise of a religious-type theocracy in is no limit in terms of publication date. Not all of the listed America. works are true sf. The first qualification was the hardest, and I worked around this by mentioning other notable books in the Alfred Bester—The Stars My Destination (1956) brief notes.