GM Texte (Sprueth Magers)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bernd & Hilla Becher Biography

P A U L A C O O P E R G A L L E R Y Bernd & Hilla Becher Biography Bernd Becher Born: Siegen, Germany 1931 Died: 2007 Hilla Becher Born: Potsdam, Germany 1934 Died: 2015 EDUCATION Bernd Becher 1976 Professor of photography at Staatlich Kunstakademie Düsseldorf 1972 Guest lecturer Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg 1957-1961 Studies in typography at Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf 1953-1956 Studies in lithography and painting at Staaliche Kunstakademie Stuttgart under Karl Rösing Hilla Becher 1972-1973 Guest Lecturer Hochschule für bildende Künste, Hamburg 1958-1961 Studies in photography at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf GRANTS & AWARDS 2014 Rheinischer Kulturpreis der Sparkassen-Kulturstiftung Rheinland 2002 The Erasmus Prize 1991 The Leon D’Oro award for sculpture at the Venice Biennale ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2019 “Bernd & Hilla Becher: Industrial Visions,” National Museum Cardiff, Wale, UK (10/26/19 – 3/1/20) “Bernd & Hilla Becher: 1962-2000,” PKM Gallery, Seoul, Korea “Bernd & Hilla Becher: Kohlebunker,” Kunstarchiv Kaiserwerth, Düsseldorf, Germany 2018 “Bernd & Hilla Becher,”Konrad Fischer Galerie, Berlin, Germany 2014 “Bernd & Hilla Becher,” Fotografien aus fünf Jahrzehnten, Konrad Fischer Galerie, Düsseldorf “Bernd & Hilla Becher,” Sprüth Magers, London 2013 “Photographische Sammlung der SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne Dia Art Foundation, New York Siegerländer Fachwerkhäuser, Orts- und Dorfansichten des Siegerlandes, Siegerländer Gruben und Hütten, Holzfördertürme in Pennsylvania, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Siegen 2012 galerija TR3, Ljubljana, Slowenia Coal Mines. Steel Mills., Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague Bernd and Hilla Becher, Sonnabend Gallery, New York Bernd & Hilla Becher. Imprimés 1964-2010, Grand Palais, Paris 2011 Bergwerke und Hütten, Industrielandschaften, Fotomuseum Winterthur 534 WEST 21ST STREET, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10011 TELEPHONE 212.255.1105 FACSIMILE 212.255.5156 P A U L A C O O P E R G A L L E R Y Blick in die Sammlung: Bernd und Hilla Becher. -

Bernd & Hilla Becher Coal Mines. Steel Mills

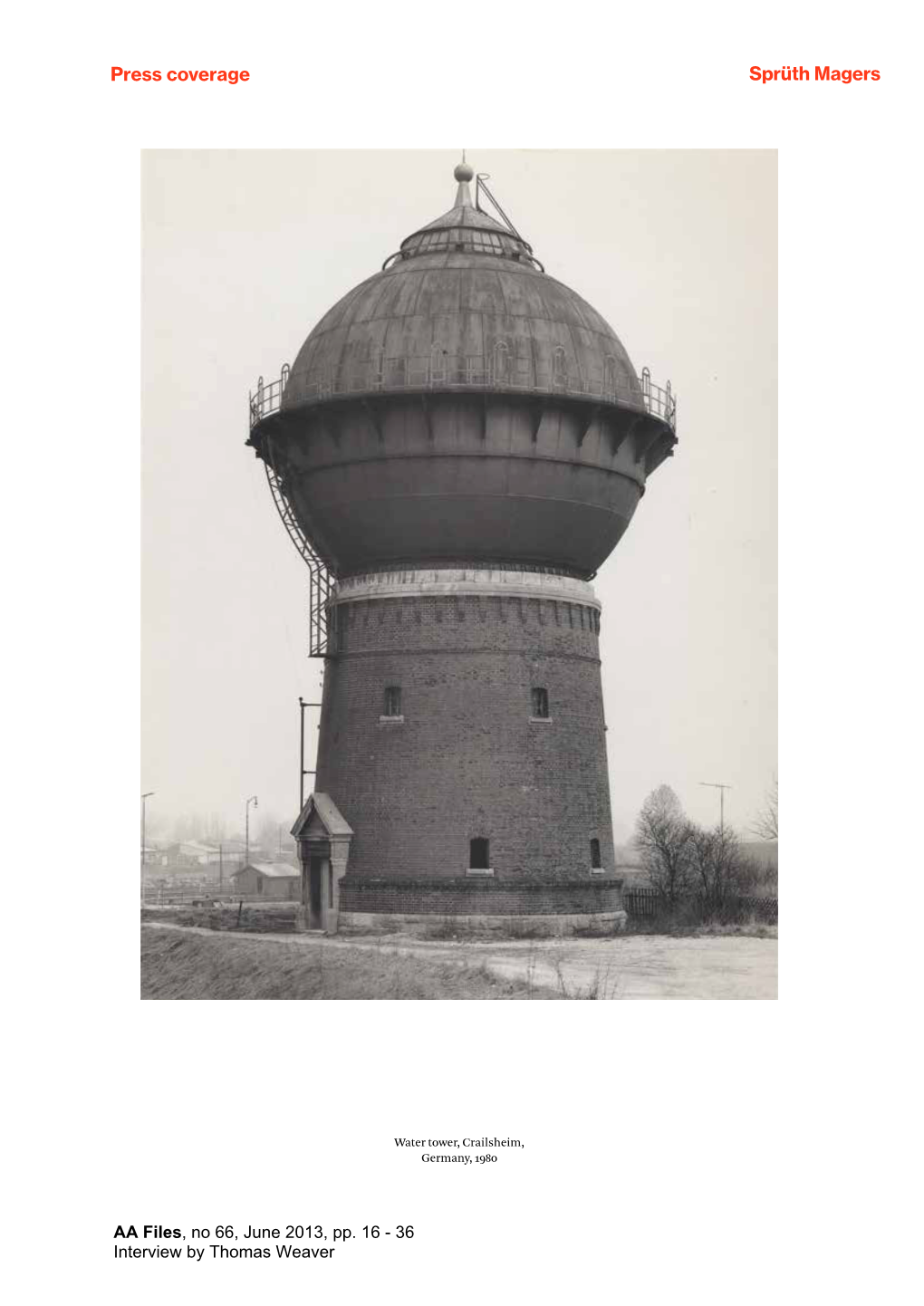

Bernd & Hilla Becher: Coal Mines. Steel Mills. 22.3.2012 – 3.6.2012 This unique representative collection of 95 black-and-white photographs by Bernd and Hilla Becher focuses on so-called “Industrial Landscapes” – a term the artists themselves use to describe a particular type of image, which does not seek to portray individual works of architecture as such, but rather the situation of heavy industry plants within their urban and landscape context. The project Coal Mines. Steel Mills. is based on works created in the Ruhr Valley (Ruhrgebiet). From as far back as the early 1960s, the mining facilities and surrounding steel mills of the area have provided both artists with a major theme for their work, one they have followed to the most minute details in their records of entire industrial zones, such as the mines Hannover in Bochum, Zollern II in Dortmund, or Concordia in Oberhausen. Photographs from the Ruhr Valley are accompanied by images from the area around Siegen in North Rhine-Westphalia as well as from the UK, France and the United States in such a way – in keeping with the artists’ intent – as to draw comparison between the language of industrial architecture as it has evolved over the course of the previous century, regardless of regional or national borders. Bernd and Hilla Becher rank among the most prominent representatives of post-war German photography, not only due to their monumental oeuvre, but also the exceptional degree of international success of the various adherents of the Düsseldorf School of Photography, which they founded. As pioneers of conceptual photography, they directly influenced several generations of German photographers. -

THE MEDIA of PHOTOGRAPHY Special Issue of the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

CALL FOR PAPERS THE MEDIA OF PHOTOGRAPHY Special Issue of the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism GUEST EDITORS Diarmuid Costello (University of Warwick) Dominic McIver Lopes (University of British Columbia) Three overlapping events occasion this proposal for a special issue of JAAC on the philosophy of photography. First, photography has matured as a visual art medium. No longer confined to specialist galleries, distribution networks, discourses, or educational programs, it has won mainstream institutional recognition – fine art museums increasingly mount major retrospectives of contemporary photographers’ work, and many of those museums now appoint curators of photography. Second, the boundary between photographic and non-photographic visual art has blurred, as lens-based technologies have found a home in a wide range of art practices from painting and theater through sculptural installation to conceptual art. Photography has become one more means at artists’ disposal; it is no longer just for photographers. Third, the rapid, ongoing development of digital imaging technologies is profoundly reshaping how photographs are made and displayed, and hence appreciated, while at the same time creating new venues for displaying photographs outside traditional art institutions. Taken together this conjunction of events raises fundamental philosophical questions about photography as an art and an aesthetic phenomenon. The proposed special issue is intended to address these questions by bringing them under a unifying theme, “the media of photography.” -

Welcome to A' Level Photography

Welcome to A’ level Photography • Now that you have decided to study A Level Photography, you will need to do a bit of preparation. This document contains information regarding the course structure, the summer project and some Photographers you should know to prepare you to start your A level in September. The purpose of studying Photography at A Level is to develop knowledge and understanding of: • Specialist vocabulary and terminology when analysing or explaining your own and others’ work • Theoretical research of a particular genre style and/or tradition • In‐depth understanding of a variety of media, techniques, and processes • Development of an idea, concept, or issue • Recording ideas and observations related to chosen lines of enquiry • Communicating a particular meaning, message, idea or feeling • There will be a pack to buy from school which will contain a selection of the and materials you will need. The cost of the pack will be approximately £50 What do I have to do in A Level Art? Photography? There are two components of the course‐ the personal investigation and the externally set assignment. The table below summarises the evidence you will produce for each component: A Level Components What will I need to do? How will I evidence this? Personal Investigation ‐Write a personal study (essay) ‐A 1000‐3000 word essay (coursework) based on your chosen theme ‐Research on a range of artists ‐Create a body of work related to and/or designers 60% a chosen theme/s ‐Exploration of a variety of ‐Create a final piece/s media, techniques and processes ‐Development of ideas in response to chosen artist/s/theme ‐Recording of ideas and observations Externally Set Assignment ‐Create preparatory studies ‐By creating a body of work (Exam) based on the theme based on the theme given. -

![Qui Était August Sander? [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7735/qui-%C3%A9tait-august-sander-1-507735.webp)

Qui Était August Sander? [1]

Sur les traces d’August Sander Par Bernard Birsinger propos recueillis par Emmanuel Bigler Résumé Bernard Birsinger nous raconte comment il est allé un jour au pays d’August Sander pour voir les lieux où le célèbre portraitiste a vécu et travaillé, en particulier là où il a photographié des paysages. Dans ce voyage, Bernard Birsinger a rencontré des témoins ayant connu August Sander, et il en a rapporté un travail photographique sur les lieux de mémoire de l’auteur des « Hommes du vingtième siècle ». Introduction - Qui était August Sander? [1] FIGURE 1 – August Sander en 1925 1 Bernard Birsinger (BBB [2]) : Dans toute quête culturelle, il est important de connaître le décor et aussi ce qui se cache derrière ce décor. Les biographies officielles à propos de Sander comme celle du Getty Museum [3], du MoMA[4], d’Aperture[5] ou de la Tate Gallery [6] de Londres suffisent-elles à nous renseigner ? Eh non. En plus, en tant que photographe, j’ai toujours encore en tête, de façon lancinante, cette phrase de la célèbre photographe américaine Diane Arbus [7] : « Rien n’est jamais comme on a dit que c’était, c’est ce que je n’ai jamais vu avant que je reconnais », phrase tirée de son livre paru en 1973 aux éditions du Chêne [8]. Et vous ne le saviez pas, ça alors? Il était donc grand temps pour moi de prendre mon bâton de pèlerin et de parcourir par monts et vaux l’Allemagne sur les traces de Sander, pour mener un double projet photographique. En un : mener un « Rephotographic Survey Project » comme celui mené à propos de Timothy O’Sullivan en 1977 [9], aux USA. -

New York Times July 15, 2003 'Critic's Notebook: for London, a Summer

New York Times July 15, 2003 ‘Critic's Notebook: For London, a Summer of Photographic Memory; Around the City, Images From Around the World’ Michael Kimmelman This city is immersed in photography exhibitions, a coincidence of scheduling, perhaps, that the museums here decided made a catchy marketing scheme. Posters and flyers advertise the “Summer of Photography.” Why not? I stopped here on the way home from the Venice Biennale, after which any exhibition that did not involve watching hours of videos in plywood sweatboxes seemed like a joy. The London shows leave you with no specific definition of what photography is now, except that it is, fruitfully, many things at once, which is a functionally vague description of the medium. You can nevertheless get a fairly clear idea of the differences between a good photograph and a bad one. In the first category are two unlike Americans: Philip-Lorca diCorcia, with a show at Whitechapel, and Cindy Sherman, at Serpentine. Into the second category falls Wolfgang Tillmans, the chic German-born, London-based photographer, who has an exhibition at Tate Britain that cheerfully disregards the idea that there might even be a difference between Categories 1 and 2. There is also the posthumous retrospective, long overdue, of Guy Bourdin, the high- concept soft-core-pornography fashion photographer for French Vogue and Charles Jourdan shoes in the 1970's and 80's, at the Victoria and Albert. And as the unofficial anchor for it all Tate Modern, which until now had apparently never organized a major photography show, has tried in one fell swoop to make up for lost time with “Cruel and Tender: The Real in the 20th Century Photograph.” The title is from Lincoln Kirstein's apt description of Walker Evans's work as “tender cruelty.” Like Tate Modern in general, “Cruel and Tender” is vast, not particularly logical and blithely skewed. -

Photographs Gathered by William T. Hillman

PRESS RELEASE | NEW YORK | 9 MARCH 2015 | FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CHRISTIE’S PRESENTS LEAVES OF LIGHT AND SHADOW: PHOTOGRAPHS GATHERED BY WILLIAM T. HILLMAN FREDERICK SOMMER, Livia, 1948. gelatin silver print, $80,000 - 120,000 RINEKE DIJKSTRA, Nicky, The Krazyhouse, Liverpool, England, January 19, 2009, $15,000 - 25,000 New York – On March 31, Christie’s will present the sale of Leaves Of Light And Shadow: Photographs Gathered By William T. Hillman, comprising 117 works judiciously acquired by William Hillman over the past three decades. With a sophisticated eye and tremendous dedication to photography, Mr. Hillman has built a comprehensive collection by pursuing consummate examples from top photographers spanning the history of the medium. In Hillman’s dedication to both photography and his hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, his primary mission over the past three decades has been to build a world-class collection that will ultimately be gifted to the Carnegie Museum of Art. “There are gaps in the vintage acquisitions and the need to support and strengthen the contemporary component of this endeavor,” Mr. Hillman has stated. Hillman personally designated each work being presented for sale, and will reinvest the funds raised by the auction back into his mission. The top lot of the auction is Waitress in a Nudist Camp, N.J., 1963 by Diane Arbus (estimate: $200,000-300,000). Additional Highlights include: HENRI CARTIER-BRESSON, Piazza della Signoria, Florence, Italy, 1933, gelatin silver print | Estimate: $100,000-150,000 Piazza della Signoria, Florence was one of Henri Cartier Bresson's favorite images. He included it in his first solo exhibition in 1933 and his last retrospective in 2003, as well as in his first monograph The Decisive Moment in 1952, and his last monograph in 2005. -

Media Release Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation

Media Release Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Frankfurt am Main, 29 April 2019 “Changing Views - 20 Years of Art Collection Deutsche Börse” at Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam • Works will be shown in four successive chapters from 3 May – 7 July 2019 • Exhibition is part of the Art Collection’s anniversary programme In light of the 20-year anniversary of the Art Collection Deutsche Börse, Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam presents “Changing Views – 20 Years of Art Collection Deutsche Börse”, an extensive range of works from the renowned collection of contemporary photography. The Art Collection Deutsche Börse comprises approximately 1,800 works from over 120 international photographers, including iconic names such as Diane Arbus, Walker Evans, Bernd & Hilla Becher, Rineke Dijkstra, Dana Lixenberg, younger photographers like Tobias Zielony and Mike Brodie, and hidden gems like Gerd Danigel or Gabriele and Helmut Nothhelfer. The exhibition period consists of four back-to-back presentations that record positions on some key themes of the collection, with works from different photographers. This concept celebrates the variety and comprehensive quality of the Art Collection Deutsche Börse. The four successive chapters are: “Germany” (3 – 19 May), “Icons” (21 May – 9 June), “Traces of Disorder” (11 – 23 June), and “Youth Culture” (25 June – 7 July). In 2019, the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation is celebrating the 20th anniversary of the Art Collection Deutsche Börse with a special programme of exhibitions and events. Under the theme “From another perspective”, the Foundation invited experts to share their views on the collection. For this special occasion, the iconic works are exchanging their familiar surroundings in the premises of the Deutsche Börse Group for the museum rooms of Foam. -

Documenta 11

1/21/2015 Frieze Magazine | Archive | Documenta 11 Documenta 11 About this article Documenta 11 Published on 09/09/02 By Thomas McEvilley Each of artistic director Okwui Enwezor’s six co-curators - Sarat Maharaj, Octavio Zaya, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez and Mark Nash - spoke briefly, followed by Enwezor himself. Maharaj identified the point of art today as ‘knowledge production’ and the point of this exhibition as ‘thinking the other’; Nash declared that the exhibition aimed to explore ‘issues of dislocation and migration’ (‘We’re all becoming transnational subjects’, he observed); Ghez stressed the unusual fact that as many as 70% of the works in the show were made explicitly for the Back to the main site occasion; Basualdo spoke of ‘establishing a new geography, or topology, of culture’; and Bauer spoke of ‘deterritorialization’. Finally, Enwezor began his reflections by referring to Chinua Achebe’s classic novel of pre-colonial Africa Things Fall Apart (1958). He spoke of the emergence of post-colonial identity, and said that he and his colleagues had aimed at something much larger than an art exhibition: they were seeking to find out what comes after imperialism. These remarks were significant because Documenta, along with the Venice Biennale, is one of the foremost venues at which the current cultural politics of the art world is laid out. In a sense the agenda proclaimed by these curators gave one a sense of déjà vu; or rather, it seemed not exactly to usher in a new era but to set a seal on an era first announced long ago. -

The Timeless Imprint of Erna Lendvai-Dircksen's Das Deutsche

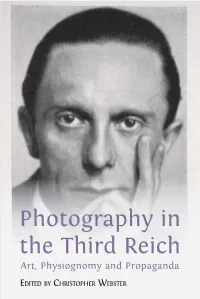

Photography in the Third Reich C Art, Physiognomy and Propaganda HRISTOPHER EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER WEBSTER This lucid and comprehensive collec� on of essays by an interna� onal group of scholars cons� tutes a photo-historical survey of select photographers who W embraced Na� onal Socialism during the Third Reich. These photographers EBSTER developed and implemented physiognomic and ethnographic photography, and, through a Selbstgleichschaltung (a self-co-ordina� on with the regime), con� nued ( to prac� ce as photographers throughout the twelve years of the Third Reich. ED .) The volume explores, through photographic reproduc� ons and accompanying analysis, diverse aspects of photography during the Third Reich, ranging from the infl uence of Modernism, the qualita� ve eff ect of propaganda photography, and the u� lisa� on of technology such as colour fi lm, to the photograph as ideological metaphor. With an emphasis on the idealised representa� on of the German body and the role of physiognomy within this representa� on, the book examines how select photographers created and developed a visual myth of the ‘master race’ and its an� theses under the auspices of the Na� onalist Socialist state. P HOTOGRAPHY Photography in the Third Reich approaches its historical source photographs as material culture, examining their produc� on, construc� on and prolifera� on. This detailed and informa� ve text will be a valuable resource not only to historians studying the Third Reich, but to scholars and students of fi lm, history of art, poli� cs, media studies, cultural studies and holocaust studies. IN THE As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Reconsidering New Objectivity: Albert Renger-Patzsch and Die

RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET E. HANKEL (Under the Direction of NELL ANDREW) ABSTRACT In December of 1928, the Munich-based publisher, Kurt Wolff released a book with a new concept: a collection of one-hundred black and white photographs by Albert Renger-Patzsch. Titled Die Welt ist schön, the book presented a remarkable diversity of subjects visually unified by Renger-Patzsch’s straight-forward aesthetic. While widely praised at the time of its release, the book exists in relative obscurity today. Its legacy was cemented by the negative criticism it received in two of Walter Benjamin’s essays, “Little History of Photography” (1931) and “The Author as Producer” (1934). This paper reexamines the book in within the context of its reception, reconsidering the book’s legacy and its ties to the New Objectivity movement in Weimar. INDEX WORDS: Albert Renger-Patzsch, Die Welt ist schön, Photography, New Objectivity, Sachlichkeit, New Vision, Painting Photography Film, Walter Benjamin, Lázsló Moholy-Nagy RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET HANKEL BA, Columbia College Chicago, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2017 © 2017 Margaret E. Hankel All Rights Reserved RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET E. HANKEL Major Professor: Nell Andrew Committee: Alisa Luxenberg Janice Simon Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2017 iv DEDICATION For my mother and father v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to those who have read this work in its various stages of completion: to my advisor, Nell Andrew, whose kind and sage guidance made this project possible, to my committee members Janice Simon and Alisa Luxenberg, to Isabelle Wallace, and to my colleague, Erin McClenathan.