'This Small Island': Britain, Size and Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of Indonesia: the Unlikely Nation?

History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page i A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page ii Short History of Asia Series Series Editor: Milton Osborne Milton Osborne has had an association with the Asian region for over 40 years as an academic, public servant and independent writer. He is the author of eight books on Asian topics, including Southeast Asia: An Introductory History, first published in 1979 and now in its eighth edition, and, most recently, The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future, published in 2000. History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iii A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA THE UNLIKELY NATION? Colin Brown History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iv First published in 2003 Copyright © Colin Brown 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Brown, Colin, A short history of Indonesia : the unlikely nation? Bibliography. -

Atlantic Disjuncture: Recent Historiography of Transoceanic Diasporas, Communities, and Empires

Cromwell, Jesse. 2019. Atlantic Disjuncture: Recent Historiography of Transoceanic Diasporas, Communities, and Empires. Latin American Research Review 54(4), pp. 1023–1030. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.631 BOOK REVIEW ESSAYS Atlantic Disjuncture: Recent Historiography of Transoceanic Diasporas, Communities, and Empires Jesse Cromwell University of Mississippi, US [email protected] This essay reviews the following works: Staying Afloat: Risk and Uncertainty in Spanish Atlantic World Trade, 1760–1820. By Jeremy Baskes. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013. Pp. ix + 381. $54.57 hardcover. ISBN: 9780804785426. The Material Atlantic: Clothing, Commerce, and Colonization in the Atlantic World, 1650–1800. By Robert S. DuPlessis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. Pp. vii + 332. $29.99 hardcover. ISBN: 9781107105911. The Temptations of Trade: Britain, Spain, and the Struggle for Empire. By Adrian Finucane. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016. Pp. 1 + 211. $45.00 hardcover. ISBN: 9780812248128. Guiana and the Shadows of Empire: Colonial and Cultural Negotiations at the Edge of the World. By Joshua R. Hyles. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2014. Pp. ix + 185. $76.56 hardcover. ISBN: 9780739187791. The Portuguese-Speaking Diaspora: Seven Centuries of Literature and the Arts. By Darlene J. Sadlier. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016. Pp. 314. $29.95 paperback. ISBN: 9781477311486. Amsterdam’s Atlantic: Print Culture and the Making of Dutch Brazil. By Michiel van Groesen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016. Pp. xx + 272. $47.50 hardcover. ISBN: 9780812248661. Atlantic history is an ever-evolving discipline. For decades, it has sought to disrupt the myopia of discrete colonial and regional studies of early modern polities by emphasizing the transimperial and transnational interactions between people of the four continents surrounding the Atlantic Ocean. -

Spring 2018 Celebrating Our 45Th

Celebrating our 45th Anniversary, p. 2 Stowe Restoration Project, pgs. 3-4 The Trevelyans of Wallington Hall, pgs. 5-6 Spring 2018 1 | From the Executive Director Dear Members & Friends, THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION 20 West 44th Street, Suite 606 New York, New York 10036-6603 2018 marks Royal Oak’s 45th Anniversary. We Churchill’s studio at Chartwell give tangible 212.480.2889 | www.royal-oak.org will celebrate this in many ways—more with a expression to the many new interpretive focus on where we are as an organization today programs that will excite visitors daily just as and what we hope for in the future. the exhibition did 35 years ago. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Honorary Chairman In reviewing some of the histories of Royal Other big news for 2018 is our appeal to help Mrs. Henry J. Heinz II Oak, I was surprised to find an event in 1983 the National Trust finish off a multi-year and Chairman that was noted as pivotal in transforming multi-task restoration effort for Stowe. Stowe Lynne L. Rickabaugh the Foundation’s relationship is one of the leading garden and Vice Chairman with the Trust from one of just landscape properties in England Prof. Susan S. Samuelson growing ‘friendship’ to one of a and has a wide significance in Treasurer serious fundraising partnership. the history of garden design in Renee Nichols Tucei The connections of this historic Europe, Russia and America (see Secretary event with what Royal Oak has pages 3-4). It is among the most Thomas M. Kelly more recently accomplished and visited Trust properties. -

Empire and English Nationalismn

Nations and Nationalism 12 (1), 2006, 1–13. r ASEN 2006 Empire and English nationalismn KRISHAN KUMAR Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Empire and nation: foes or friends? It is more than pious tribute to the great scholar whom we commemorate today that makes me begin with Ernest Gellner. For Gellner’s influential thinking on nationalism, and specifically of its modernity, is central to the question I wish to consider, the relation between nation and empire, and between imperial and national identity. For Gellner, as for many other commentators, nation and empire were and are antithetical. The great empires of the past belonged to the species of the ‘agro-literate’ society, whose central fact is that ‘almost everything in it militates against the definition of political units in terms of cultural bound- aries’ (Gellner 1983: 11; see also Gellner 1998: 14–24). Power and culture go their separate ways. The political form of empire encloses a vastly differ- entiated and internally hierarchical society in which the cosmopolitan culture of the rulers differs sharply from the myriad local cultures of the subordinate strata. Modern empires, such as the Soviet empire, continue this pattern of disjuncture between the dominant culture of the elites and the national or ethnic cultures of the constituent parts. Nationalism, argues Gellner, closes the gap. It insists that the only legitimate political unit is one in which rulers and ruled share the same culture. Its ideal is one state, one culture. Or, to put it another way, its ideal is the national or the ‘nation-state’, since it conceives of the nation essentially in terms of a shared culture linking all members. -

Some Pages from the Book

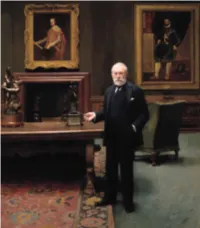

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

Hett-Syll-80020-19

The Graduate Center of the City University of New York History Department Hist 80200 Literature of Modern Europe II Thursdays 4:15-6:15 GC 3310A Prof. Benjamin Hett e-mail [email protected] GC office 5404 Office hours Thursdays 2:00-4:00 or by appointment Course Description: This course is intended to provide an introduction to the major themes and historians’ debates on modern European history from the 18th century to the present. We will study a wide range of literature, from what we might call classic historiography to innovative recent work; themes will range from state building and imperialism to war and genocide to culture and sexuality. After completing the course students should have a solid basic grounding in the literature of modern Europe, which will serve as a basis for preparation for oral exams as well as for later teaching and research work. Requirements: In a small seminar class of this nature effective class participation by all students is essential. Students will be expected to take the lead in class discussions: each week one student will have the job of introducing the literature for the week and to bring to class questions for discussion. Over the semester students will write a substantial historiographical paper (approximately 20 pages or 6000 words) on a subject chosen in consultation with me, due on the last day of class, May 13. The paper should deal with a question that is controversial among historians. Students must also submit two short response papers (2-3 pages) on readings for two of the weekly sessions of the course, and I will ask for annotated bibliographies for your historiographical papers on March 28. -

Political Science 279/479 War and the Nation-State

Political Science 279/479 War and the Nation-State Hein Goemans Course Information: Harkness 320 Fall 2010 Office Hours: Monday 4{5 Thursday 16:50{19:30 [email protected] Harkness 329 This course examines the development of warfare and growth of the state. In particular, we examine the phenomenon of war in its broader socio-economic context between the emergence of the modern nation-state and the end of World War II. Students are required to do all the reading. Student are required to make a group presentation in class on the readings for one class (25% of the grade), and there will be one big final (75%). Course Requirements Participation and a presentation in the seminar comprises 25% of your grade. A final exam counts for 75%. The final exam is given during the period scheduled by the University. In particular instances, students may substitute a serious research paper for the final. Students interested in the research paper option should approach me no later than one week after the mid-term. Academic Integrity Be familiar with the University's policies on academic integrity and disciplinary action (http://www.rochester.edu/living/urhere/handbook/discipline2.html#XII). Vi- olators of University regulations on academic integrity will be dealt with severely, which means that your grade will suffer, and I will forward your case to the Chair of the College Board on Academic Honesty. The World Wide Web A number of websites will prove useful: 1. General History of the 20th Century • http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/war/ • http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/20centry.htm • http://www.fsmitha.com/ 2. -

Imperialism Tate Britain: Colonialism Tate Britain Has Over 500 Pieces of Art That Are Related to British Colonialism. There Ar

Imperialism Tate Britain: Colonialism Tate Britain has over 500 pieces of art that are related to British Colonialism. There are portraits, propaganda and photographs. Mutiny at the Margin: The Indian Uprising of 1857 2007 saw the 150th Anniversary of the Indian Uprising (also known as the ‘Mutiny') of 1857-58. One of the best-known episodes of both British imperial and South Asian history and a seminal event for Anglo-Indian relations, 1857 has yet to be the subject of a substantial revisionist history British Postal Museum and Archive: British Empire Exhibition Great Britain’s first commemorative stamps were issued on 23 April 1924 – this marked the first day of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley. British Cartoon Archive: British Empire The British Cartoon Archive has a collection of 280 contemporary cartoons that are related to the British Empire. The Word on the Street: Emigration This contains a collection of 44 ballads that are related to British emigration during the 1800/1900’s. British Pathe: Empire British Pathe has a collection of contemporary newsreels that are related to the empire. Included, for example, is footage from Empire Day celebration in 1933. The British Library: Asians in Britain These webpages trace the long history of Asians in Britain, focusing on the period 1858-1950. They explore the subject through contemporary accounts, posters, pamphlets, diaries, newspapers, political reports and illustrations, all evidence of the diverse and rich contributions Asians have made to British life. The National Archives: British Empire The National Archives has an exhibition that analyses the growth of the British Empire. -

Hollsten, Laura. "Controlling Nature and Transforming Landscapes in the Early Modern Caribbean." Global Environment 1 (2008): 80–113

Full citation: Hollsten, Laura. "Controlling Nature and Transforming Landscapes in the Early Modern Caribbean." Global Environment 1 (2008): 80–113. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/4218. First published: http://www.globalenvironment.it. Rights: All rights reserved. Made available on the Environment & Society Portal for nonprofit educational purposes only, courtesy of Gabriella Corona, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche / National Research Council of Italy (CNR), and XL edizioni s.a.s. Controlling Nature and Transforming Landscapes in the Early Modern Caribbean Laura Hollsten he Early Modern Caribbean is a highly in- teresting area for the global as well as the environmental historian.1 h e Caribbean islands were some of the most important colonies in the seventeenth century and part of the international trade network as one of the cornerstones of the so-called T “triangular trade” between Europe, Africa and the Americas. h e growth of markets and buying power in Europe stimulated investments in sugar plan- tations. Westbound European ships, on their way to what they ini- tially thought of as India, i rst arrived here bringing with them peo- ple, animals, diseases, arms and the beginnings of a new culture. h e Caribbean has sometimes been characterised as a place where people, plants and animals were acclimatised before they entered the mainland of America. Mary Louise Pratt’s concept of a contact zone, designating an area of contact between dif erent peoples in a colonial situation, can be applied to contacts between biotypes, animals and plants, as well as humans.2 h e seventeenth-century Caribbean was a contact zone for dif erent peoples, as well as animals and plants. -

Island Stories

ISLAND STORIES 9781541646926-text.indd 1 11/7/19 2:48 PM ALSO BY DAVID REYNOLDS The Creation of the Anglo-American Alliance: A Study in Competitive Cooperation, 1937–1941 An Ocean Apart: The Relationship between Britain and America in the Twentieth Century (with David Dimbleby) Britannia Overruled: British Policy and World Power in the Twentieth Century The Origins of the Cold War in Europe (editor) Allies at War: The Soviet, American and British Experience, 1939–1945 (co-edited with Warren F. Kimball and A. O. Chubarian) Rich Relations: The American Occupation of Britain, 1942–1945 One World Divisible: A Global History since 1945 From Munich to Pearl Harbor: Roosevelt’s America and the Origins of the Second World War In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War From World War to Cold War: Churchill, Roosevelt and the International History of the 1940s Summits: Six Meetings that Shaped the Twentieth Century America, Empire of Liberty: A New History FDR’s World: War, Peace, and Legacies (co-edited with David B. Woolner and Warren F. Kimball) The Long Shadow: The Great War and the Twentieth Century Transcending the Cold War: Summits, Statecraft, and the Dissolution of Bipolarity in Europe, 1970–1990 (co-edited with Kristina Spohr) The Kremlin Letters: Stalin’s Wartime Correspondence with Churchill and Roosevelt (with Vladimir Pechatnov) 9781541646926-text.indd 2 11/7/19 2:48 PM ISLAND STORIES AN UNCONVENTIONAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN DAVID REYNOLDS New York 9781541646926-text.indd 3 11/7/19 2:48 PM Copyright © 2020 by David Reynolds Cover design by XXX Cover image [Credit here] Cover copyright © 2020 Hachette Book Group, Inc. -

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (AZ Listing by Episode Title. Prices Include

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (A-Z listing by episode title. Prices include taxes and shipping within Canada) Catalog is updated at the end of each month. For current month’s listings, please visit: http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/schedule/ Transcript = readable, printed transcript CD = titles are available on CD, with some exceptions due to copyright = book 104 Pall Mall (2011) CD $18 foremost public intellectuals, Jean The Academic-Industrial Ever since it was founded in 1836, Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Complex London's exclusive Reform Club Spelman Rockefeller Professor of (1982) Transcript $14.00, 2 has been a place where Social and Political Ethics, Divinity hours progressive people meet to School, The University of Chicago. Industries fund academic research discuss radical politics. There's In addition to her many award- and professors develop sideline also a considerable Canadian winning books, Professor Elshtain businesses. This blurring of the connection. IDEAS host Paul writes and lectures widely on dividing line between universities Kennedy takes a guided tour. themes of democracy, ethical and the real world has important dilemmas, religion and politics and implications. Jill Eisen, producer. 1893 and the Idea of Frontier international relations. The 2013 (1993) $14.00, 2 hours Milton K. Wong Lecture is Acadian Women One hundred years ago, the presented by the Laurier (1988) Transcript $14.00, 2 historian Frederick Jackson Turner Institution, UBC Continuing hours declared that the closing of the Studies and the Iona Pacific Inter- Acadians are among the least- frontier meant the end of an era for religious Centre in partnership with known of Canadians. -

Curriculum Vitae (Updated August 1, 2021)

DAVID A. BELL SIDNEY AND RUTH LAPIDUS PROFESSOR IN THE ERA OF NORTH ATLANTIC REVOLUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Curriculum Vitae (updated August 1, 2021) Department of History Phone: (609) 258-4159 129 Dickinson Hall [email protected] Princeton University www.davidavrombell.com Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 @DavidAvromBell EMPLOYMENT Princeton University, Director, Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies (2020-24). Princeton University, Sidney and Ruth Lapidus Professor in the Era of North Atlantic Revolutions, Department of History (2010- ). Associated appointment in the Department of French and Italian. Johns Hopkins University, Dean of Faculty, School of Arts & Sciences (2007-10). Responsibilities included: Oversight of faculty hiring, promotion, and other employment matters; initiatives related to faculty development, and to teaching and research in the humanities and social sciences; chairing a university-wide working group for the Johns Hopkins 2008 Strategic Plan. Johns Hopkins University, Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities (2005-10). Principal appointment in Department of History, with joint appointment in German and Romance Languages and Literatures. Johns Hopkins University. Professor of History (2000-5). Johns Hopkins University. Associate Professor of History (1996-2000). Yale University. Assistant Professor of History (1991-96). Yale University. Lecturer in History (1990-91). The New Republic (Washington, DC). Magazine reporter (1984-85). VISITING POSITIONS École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Visiting Professor (June, 2018) Tokyo University, Visiting Fellow (June, 2017). École Normale Supérieure (Paris), Visiting Professor (March, 2005). David A. Bell, page 1 EDUCATION Princeton University. Ph.D. in History, 1991. Thesis advisor: Prof. Robert Darnton. Thesis title: "Lawyers and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Paris (1700-1790)." Princeton University.