UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title Robert B. Stevens: UCSC Chancellorship, 1987-1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/95h8k9w0 Authors Stevens, Robert Jarrell, Randall Regional History Project, UCSC Library Publication Date 1999-05-21 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/95h8k9w0#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction The Regional History Project conducted six interviews with UCSC Chancellor Robert B. Stevens during June and July, 1991, as part of its University History series. Stevens was appointed the campus’s fifth chancellor by UC President David P. Gardner in July, 1987, and served until July, 1991. He was the second UCSC chancellor (following Chancellor Emeritus Robert L. Sinsheimer) recruited from a private institution. Stevens was born in England in 1933 and first came to the United States when he was 23. He was educated at Oxford University (B.A., M.A., B.C.L., and D.C.L.) and at Yale University (L.L.M.) and became an American citizen in 1971. An English barrister, Stevens has strong research interests in legal history and education in the United States and England. He served as chairman of the Research Advisory Committee of the American Bar Foundation, has written a half dozen books on legal history and social legislation, and numerous papers on American legal scholarship and comparative Anglo-American legal history. Prior to his appointment at UCSC he served for almost a decade as president of Haverford College from 1978 until 1987. From 1959 to 1976 he was a professor of law at Yale University. -

Cover Letter for KZSC Advisor Position I'm Writing to Apply for The

Cover Letter for KZSC Advisor Position I'm writing to apply for the job of KZSC advisor. With my passions, experience and skills, I think I would be a great fit for the job. I've worked in and around radio since I started on my college radio station, WEOS FM, as a freshman. I've hosted and produced shows and I've been a nationally-published radio columnist. I had the radio bug from the time I was young. I'm one of the rare breed who love the medium and always have. But I didn't choose it as a full time profession. Instead I focused on journalism and teaching, both of which gave me skills I would bring to UCSC. I've been a reporter and editor for three decades and a teacher for half that time. I worked at the Santa Cruz Mercury News for 22 years and was a radio writer for much of it. I studied the industry and wrote columns critiquing it. During that time I got to know many people at all levels of the business and appeared on media outlets from Howard Stern to Nightline. I've also taught broadcasting at Cabrillo and De Anza Colleges. I am currently the Chairman of the Journalism Department at Cabrillo, where I've gotten experience that would help at KZSC. I've dealt with hiring and firing; I've taught some 200 students a year; I've managed the department's budget; and I've been the advisor to the school's newspaper. I manage a radio course through the school where students produce a show on KSCO-AM in return for time as interns at the station. -

CRITICAL THEORY INSTITUTE University of California, Irvine CTI

CRITICAL THEORY INSTITUTE University of California, Irvine CTI 2011 Wellek Library Lecture Series Donna Haraway Professor Emerita, History of Consciousness, University of California, Santa Cruz Playing Cat’s Cradle with Companion Species Monday, May 2nd, 5-7pm Tuesday, May 3rd, 5-7pm Thursday, May 5th, 5-7pm Humanities Gateway, 1030 Contact Information: Critical Theory Institute University of California, Irvine 433 Krieger Hall Irvine, CA 92697-5525 Phone (949) 824-5583 Fax (949) 824-2767 Director: Kavita Philip Admin. Coordinator: Lisa Clark [email protected] www.humanities.uci.edu/critical For information concerning accommodations for disabilities, please contact Lisa Clark at 949-824-5583 Donna Haraway: A Bibliography for the Occasion of the 31st Wellek Library Lectures Compiled by John Novak, UCI Research Librarian An electronic version of this and previous Wellek Library Lecture bibliographies with working electronic links will be maintained at this Web site: http://www.lib.uci.edu/about/publications/wellek/wellek-series.html Direct links to electronic materials may be accessed on-campus. Off-campus access is for the UCI community via the VPN. For more information, visit the following Web site: http://www.lib.uci.edu/how/connect-from-off-campus.html Table of Contents for Bibliography Works by Haraway ..................................................... 1 Haraway Interviews and Biographies ....................... 16 Selected Works About or Utilizing Haraway ............. 18 Works by Haraway 1975 "The Transformation of the Left in Science: Radical Associations in Britain in the 30s and the U.S.A. in the 60s." Soundings 58 4 (1975): 441-62. Print. Call Number: Langson Bound Periodicals BV 1460 C6 1976 Crystals, Fabrics, and Fields: Metaphors of Organicism in Twentieth-Century Developmental Biology. -

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title "It Became My Case Study": Professor Michael Cowan's Four Decades at UC Santa Cruz Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3j5438d7 Authors Cowan, Michael Reti, Irene Publication Date 2013-01-11 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3j5438d7#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California, Santa Cruz University Library “It Became My Case Study” Professor Michael Cowan’s Four Decades at UC Santa Cruz Interviewed and Edited by Irene Reti Santa Cruz 2013 This manuscript is covered by copyright agreement between Michael Cowan and the Regents of the University of California dated December 3, 2012. Under “fair use” standards, excerpts of up to six hundred words (per interview) may be quoted without the Regional History Project’s permission as long as the materials are properly cited. Quotations of more than six hundred words require the written permission of the University Librarian and a proper citation and may also require a fee. Under certain circumstances, not-for-profit users may be granted a waiver of the fee. To contact the Regional History Project: [email protected] or Regional History Project McHenry Library, UC Santa Cruz 1156 High Street Santa Cruz, CA 95064 Phone: 831-459-2847 Table of Contents Introduction vii Early Life 12 Yale University 23 Senior Thesis on the Boy Scouts of America 34 Graduate Work in American Studies at Yale 37 Teaching at Yale University 43 Coming to the University of California, -

University of California Santa Cruz Marxism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ MARXISM AND CONSTITUENT POWER IN LATIN AMERICA: THEORY AND HISTORY FROM THE MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY THROUGH THE PINK TIDE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY OF CONSCIOUSNESS with an emphasis in POLITICS by Robert Cavooris December 2019 The dissertation of Robert Cavooris is approved: _______________________________________ Robert Meister, Chair _______________________________________ Guillermo Delgado-P. _______________________________________ Juan Poblete _______________________________________ Megan Thomas _________________________________________ Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Robert Cavooris, 2019. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements and Dedication vi Preface x Introduction 1 Chapter 1 41 Intellectuals and Political Strategy: Hegemony, Posthegemony, and Post-Marxist Theory in Latin America Chapter 2 83 Constituent Power and Capitalism in the Works of René Zavaleta Mercado Chapter 3 137 Bolivian Insurgency and the Early Work of Comuna Chapter 4 204 Potentials and Limitations of the Bolivian ‘Process of Change’ Conclusions 261 Appendix: List of Major Works by Comuna (1999–2011) 266 Bibliography 271 iii Abstract Marxism and Constituent Power in Latin America: Theory and History from the Mid-Twentieth Century through The Pink Tide Robert Cavooris Throughout the history of Marxist theory and practice in Latin America, certain questions recur. What is the relationship between political and social revolution? How can state institutions serve as tools for political change? What is the basis for mass collective political agency? And how can intellectual work contribute to broader emancipatory political movements? Through textual and historical analysis, this dissertation examines how Latin American intellectuals and political actors have reframed and answered these questions in changing historical circumstances. -

Early Campus History

University of California, Santa Cruz University Library DEAN E. McHENRY VOLUME III UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ: EARLY CAMPUS HISTORY 1958-1969 Interviewed by Elizabeth Spedding Calciano Edited by E.S.C. and Randall Jarrell Santa Cruz 1987 ii Dean E. McHenry Inauguration as Chancellor University of California, Santa Cruz Upper Quarry May 3, 1966 iii All uses of this manuscript are covered by an agreement between the Regents of the University of California and Dean E. McHenry, dated February 20, 1971. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes upon his death unless he gives written permission to the Office of the University Librarian and/or the Office of the Regional History Project that the manuscript is to be available at an earlier date. With the exception of certain rights granted to Dean E. McHenry, all literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The University Library of the University of California, Santa Cruz. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the University Librarian of the University of California, Santa Cruz. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume III INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... VIII JULY 10, 1968 9:45 A.M. ................................................................................................................................. 1 PROVOSTS ................................................................................................................................................................1 -

2017-2018 Academic Year 02

CELEBRATING THE HUMANITIES 2017-2018 Academic Year 02 LETTER FROM THE DEAN TYLER STOVALL As we come to the end of another academic year, many of us are no doubt grateful for the relative calm we have experienced since last year. National politics remains turbulent, but there have been no new changes or transitions comparable to those of a year ago. If last year was a time of drama, this has been more one of reassessment and new beginnings. It has been my pleasure to welcome new colleagues to the Humanities Division. History of Consciousness has two new faculty, Banu Bargu and Massimiliano Tomba, whose presence has brought new dynamism to the department. Ryan Bennett and Amanda Rysling joined the Linguistics department as assistant professors. I’m also pleased to welcome Literature professor Marlene Tromp, who so wanted to join us she consented to accept an administrative position as Campus Provost/Executive Vice Chancellor! At the same time, I must say farewell to some valued colleagues. Professors Tyrus Miller and Deanna Shemek are moving to faculty positions at UC Irvine, where Tyrus will also serve as Dean of the Humanities. Professors Bettina Aptheker, Jim McCloskey, and Karen Tei Yamashita retired from the university, although I hope they will remain active as emeriti faculty. Finally, I must acknowledge and mourn the passing of professor emeritus Hayden V. White. One of the most renowned and influential faculty members at UC Santa Cruz, Hayden White left a rich legacy to History of Consciousness, the Humanities, and UC Santa Cruz in general. This has also been a year of new initiatives. -

The UC Santa Cruz Budget – a Bird's Eye View

Office of Planning and Budget 2012-13 Edition The UC Santa Cruz Budget – A Bird’s Eye View Message from Office of Planning and Budget… December 2012 On behalf of the staff in Planning and Budget, I am happy to provide you with the 2012-13 edition of The Those birds have a good view of the budget. Birds Eye View. This document provides a unique look at the permanent operating budget for the campus and each of its major units. It includes recent data on the degrees conferred, the majors of our students, the number of faculty budgeted in each department, enrollments by department, and extramural awards. You can find it on the web at http://planning.ucsc.edu/budget/reports/birdseye. UCSC has implemented cuts in each of the past five years. While the cuts have been primarily in the core-funded areas, the impact has been felt throughout the campus. The passage of Proposition 30—and steps taken by the UC Office of the President to renew discussions with the State concerning the longer term funding needs of the University—represents the prospect for California to put public higher education back on a pathway toward fiscal stability. If the State and the UC Regents each agree on a multi-year financial plan for UC, this will create an opportunity for UCSC to create our own multi-year path. While additional cuts will be needed in 2013-14 to address the budget shortfall from 2012-13, we are cautiously optimistic that we can begin to plan for more budget stability. -

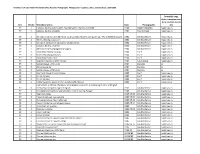

UA 128 Inventory Photographer Neg Slide Cs Series 8 16

Inventory: UA 128, Public Information Office Records: Photographs. Photographer negatives, slides, contact sheets, 1980-2005 Format(s): negs, slides, transparencies (trn), contact sheets Box Binder Title/Description Date Photographer (cs) 39 1 Campus, faculty and students. Marketing firm: Barton and Gillet. 1980 Robert Llewellyn negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Paul Schraub negatives, cs 39 2 Set construction; untitled Porter sculpture (aka"Wave"); computer lab; "Flying Weenies"poster 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Tennis, fencing; classroom 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Bike path; computers; costumes; sound system; 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Admissions special programs (2 pages) 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown family housing 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Student family apartments 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown Santa Cruz 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Special Collections, UCSC Library 1984 Lucas Stang negatives, cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Childcare center 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 East Field House; Crown College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Performing Arts; Oakes; Porter sculpture (The Wave) 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs Jack Schaar, professor of politics; Elena Baskin Visual Arts, printmaking studio; undergrad 39 3 chemistry; Computer engineering lab -

Agenda Regular Meeting Council of San Benito County Governments

AGENDA REGULAR MEETING COUNCIL OF SAN BENITO COUNTY GOVERNMENTS DATE: Thursday, April 16, 2015 3:00 p.m. LOCATION: Board of Supervisors Chambers 481 Fourth St., Hollister, CA 95023 DIRECTORS: Chair Jerry Muenzer, Vice Chair Tony Boch Directors Anthony Botelho, Victor Gomez, and Ignacio Velazquez Alternates: San Benito County: Jaime De La Cruz; City of Hollister: Mickie Luna; City of San Juan Bautista: Jim West Ex Officio: Caltrans District 5 Persons who wish to address the Board of Directors must complete a Speaker Card and give it to the Clerk prior to addressing the Board. Those who wish to address the Board on an agenda item will be heard when the Chairperson calls for comments from the audience. Following recognition, persons desiring to speak are requested to advance to the podium and state their name and address. After hearing audience comments, the Public Comment portion of the agenda item will be closed. The Opportunity to address the Board of Directors on items of interest not appearing on the agenda will be provided during Section C. Public Comment. 3:00 P.M. CALL TO ORDER A. Pledge of Allegiance B. Verification of Certificate of Posting C. Public Comment (Opportunity to address the Board on items of interest on a subject matter within the jurisdiction of the Council of Governments and not appearing on the agendas. No action may be taken unless provided by Govt. Code Sec. 54954.2 Speakers are limited to 3 minutes.) D. Executive Director’s Report E. Caltrans Report – Gubbins/Loe F. Board of Directors’ Reports CONSENT AGENDA: (These matters shall be considered as a whole and without discussion unless a particular item is removed from the Consent Agenda. -

The Postmodern Condition: a Report on Knowledge

The Postlllodern Condition: A Report on Kno-wledge Jean-Fran�ois Lyotard Translation from the French by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi Foreword by Fredric Jameson Theory and History of Literature, Volume 10 £P Manchester University Press . .� � orip��?�;� l c.:�-•-"� t3o Thk book wu F �u rt�pport sur I� savoir, copyright© 1979 by Les Editions de Minuit. English translation and Foreword copyright© 1984 by the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Published in the United Kingdom by Manchester University Press. Oxford Road Manchester M13 9PL Printed in the United States of America. British LibruyCatalopaing in Publication Data Lyotard, jean-Fran�is The postmodem condition- (Theory and history of literature) 1. Knowledge, Theory of I. Title 11. La condition postmodeme. English Ill. Series 001 Z361 ISBN 0·7190-1454-9 ISBN o-7 1 90-1450-6 pbk. "Answering the Question : "What Is Postmodemism?" appears in this book counesy of the University of Wisconsin Press (English translation of this essay by Regis Durand copyright© 1983 by University of Wisconsin Press; the essay appears in lhab Hassan and Sally Hassan , eds., lnno11ation/R�no11ation !Madison: University of Wisconsin Press,198 3) ) and counesy of jean Piel, editor of Critiqu�. where the essay originally appeared as "Reponse a Ia question: qu'est-ce que le postmodc:rnc:?" in Critiqu�. number 419 (April 1982). Contents Foreword by Fredric jameson vii Introduction xxiii 1. The Field : Knowledge in Computerized Societies 3 2. The Problem : Legitimation 6 3. The Method: Language Games 9 4. The Nature of the Social Bond: The Modern Alternative 11 S. -

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title The Critical World of Harry Berger, Jr.: An Oral History Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4rg173mr Authors Vanderscoff, Cameron Reti, Irene Berger, Harry, Jr. Publication Date 2015-03-19 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4rg173mr#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Critical World of Harry Berger, Jr.: An Oral History Interviewed by Cameron Vanderscoff Edited by Cameron Vanderscoff and Irene Reti Santa Cruz University of California, Santa Cruz University Library 2015 This oral history is covered by a copyright agreement between Harry Berger, Jr. and the Regents of the University of California dated March 2, 2015. Under “fair use” standards, excerpts of up to six hundred words (per interview) may be quoted without the University Library’s permission as long as the materials are properly cited. Quotations of more than six hundred words require the written permission of the Head of Special Collections and Archives and a proper citation and may also require a fee. Under certain circumstances, not-for-profit users may be granted a waiver of the fee. For permission contact: Irene Reti at [email protected], Oral Historian, Special Collections and Archives, McHenry Library, UC Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, 95064. Phone: 831-459-2847. Contents Interview History 1 Childhood: New York, New Rochelle 5 Education: High School, Yale and Early Writing 9 Anti-Semitism at Yale 12 Superheterodyne Radios, “Dickheads,” and Jazz in