UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY INSTITUTE University of California, Irvine CTI

CRITICAL THEORY INSTITUTE University of California, Irvine CTI 2011 Wellek Library Lecture Series Donna Haraway Professor Emerita, History of Consciousness, University of California, Santa Cruz Playing Cat’s Cradle with Companion Species Monday, May 2nd, 5-7pm Tuesday, May 3rd, 5-7pm Thursday, May 5th, 5-7pm Humanities Gateway, 1030 Contact Information: Critical Theory Institute University of California, Irvine 433 Krieger Hall Irvine, CA 92697-5525 Phone (949) 824-5583 Fax (949) 824-2767 Director: Kavita Philip Admin. Coordinator: Lisa Clark [email protected] www.humanities.uci.edu/critical For information concerning accommodations for disabilities, please contact Lisa Clark at 949-824-5583 Donna Haraway: A Bibliography for the Occasion of the 31st Wellek Library Lectures Compiled by John Novak, UCI Research Librarian An electronic version of this and previous Wellek Library Lecture bibliographies with working electronic links will be maintained at this Web site: http://www.lib.uci.edu/about/publications/wellek/wellek-series.html Direct links to electronic materials may be accessed on-campus. Off-campus access is for the UCI community via the VPN. For more information, visit the following Web site: http://www.lib.uci.edu/how/connect-from-off-campus.html Table of Contents for Bibliography Works by Haraway ..................................................... 1 Haraway Interviews and Biographies ....................... 16 Selected Works About or Utilizing Haraway ............. 18 Works by Haraway 1975 "The Transformation of the Left in Science: Radical Associations in Britain in the 30s and the U.S.A. in the 60s." Soundings 58 4 (1975): 441-62. Print. Call Number: Langson Bound Periodicals BV 1460 C6 1976 Crystals, Fabrics, and Fields: Metaphors of Organicism in Twentieth-Century Developmental Biology. -

University of California Santa Cruz Marxism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ MARXISM AND CONSTITUENT POWER IN LATIN AMERICA: THEORY AND HISTORY FROM THE MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY THROUGH THE PINK TIDE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY OF CONSCIOUSNESS with an emphasis in POLITICS by Robert Cavooris December 2019 The dissertation of Robert Cavooris is approved: _______________________________________ Robert Meister, Chair _______________________________________ Guillermo Delgado-P. _______________________________________ Juan Poblete _______________________________________ Megan Thomas _________________________________________ Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Robert Cavooris, 2019. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements and Dedication vi Preface x Introduction 1 Chapter 1 41 Intellectuals and Political Strategy: Hegemony, Posthegemony, and Post-Marxist Theory in Latin America Chapter 2 83 Constituent Power and Capitalism in the Works of René Zavaleta Mercado Chapter 3 137 Bolivian Insurgency and the Early Work of Comuna Chapter 4 204 Potentials and Limitations of the Bolivian ‘Process of Change’ Conclusions 261 Appendix: List of Major Works by Comuna (1999–2011) 266 Bibliography 271 iii Abstract Marxism and Constituent Power in Latin America: Theory and History from the Mid-Twentieth Century through The Pink Tide Robert Cavooris Throughout the history of Marxist theory and practice in Latin America, certain questions recur. What is the relationship between political and social revolution? How can state institutions serve as tools for political change? What is the basis for mass collective political agency? And how can intellectual work contribute to broader emancipatory political movements? Through textual and historical analysis, this dissertation examines how Latin American intellectuals and political actors have reframed and answered these questions in changing historical circumstances. -

Early Campus History

University of California, Santa Cruz University Library DEAN E. McHENRY VOLUME III UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ: EARLY CAMPUS HISTORY 1958-1969 Interviewed by Elizabeth Spedding Calciano Edited by E.S.C. and Randall Jarrell Santa Cruz 1987 ii Dean E. McHenry Inauguration as Chancellor University of California, Santa Cruz Upper Quarry May 3, 1966 iii All uses of this manuscript are covered by an agreement between the Regents of the University of California and Dean E. McHenry, dated February 20, 1971. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes upon his death unless he gives written permission to the Office of the University Librarian and/or the Office of the Regional History Project that the manuscript is to be available at an earlier date. With the exception of certain rights granted to Dean E. McHenry, all literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The University Library of the University of California, Santa Cruz. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the University Librarian of the University of California, Santa Cruz. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume III INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... VIII JULY 10, 1968 9:45 A.M. ................................................................................................................................. 1 PROVOSTS ................................................................................................................................................................1 -

2017-2018 Academic Year 02

CELEBRATING THE HUMANITIES 2017-2018 Academic Year 02 LETTER FROM THE DEAN TYLER STOVALL As we come to the end of another academic year, many of us are no doubt grateful for the relative calm we have experienced since last year. National politics remains turbulent, but there have been no new changes or transitions comparable to those of a year ago. If last year was a time of drama, this has been more one of reassessment and new beginnings. It has been my pleasure to welcome new colleagues to the Humanities Division. History of Consciousness has two new faculty, Banu Bargu and Massimiliano Tomba, whose presence has brought new dynamism to the department. Ryan Bennett and Amanda Rysling joined the Linguistics department as assistant professors. I’m also pleased to welcome Literature professor Marlene Tromp, who so wanted to join us she consented to accept an administrative position as Campus Provost/Executive Vice Chancellor! At the same time, I must say farewell to some valued colleagues. Professors Tyrus Miller and Deanna Shemek are moving to faculty positions at UC Irvine, where Tyrus will also serve as Dean of the Humanities. Professors Bettina Aptheker, Jim McCloskey, and Karen Tei Yamashita retired from the university, although I hope they will remain active as emeriti faculty. Finally, I must acknowledge and mourn the passing of professor emeritus Hayden V. White. One of the most renowned and influential faculty members at UC Santa Cruz, Hayden White left a rich legacy to History of Consciousness, the Humanities, and UC Santa Cruz in general. This has also been a year of new initiatives. -

The UC Santa Cruz Budget – a Bird's Eye View

Office of Planning and Budget 2012-13 Edition The UC Santa Cruz Budget – A Bird’s Eye View Message from Office of Planning and Budget… December 2012 On behalf of the staff in Planning and Budget, I am happy to provide you with the 2012-13 edition of The Those birds have a good view of the budget. Birds Eye View. This document provides a unique look at the permanent operating budget for the campus and each of its major units. It includes recent data on the degrees conferred, the majors of our students, the number of faculty budgeted in each department, enrollments by department, and extramural awards. You can find it on the web at http://planning.ucsc.edu/budget/reports/birdseye. UCSC has implemented cuts in each of the past five years. While the cuts have been primarily in the core-funded areas, the impact has been felt throughout the campus. The passage of Proposition 30—and steps taken by the UC Office of the President to renew discussions with the State concerning the longer term funding needs of the University—represents the prospect for California to put public higher education back on a pathway toward fiscal stability. If the State and the UC Regents each agree on a multi-year financial plan for UC, this will create an opportunity for UCSC to create our own multi-year path. While additional cuts will be needed in 2013-14 to address the budget shortfall from 2012-13, we are cautiously optimistic that we can begin to plan for more budget stability. -

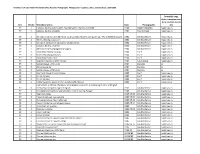

UA 128 Inventory Photographer Neg Slide Cs Series 8 16

Inventory: UA 128, Public Information Office Records: Photographs. Photographer negatives, slides, contact sheets, 1980-2005 Format(s): negs, slides, transparencies (trn), contact sheets Box Binder Title/Description Date Photographer (cs) 39 1 Campus, faculty and students. Marketing firm: Barton and Gillet. 1980 Robert Llewellyn negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Paul Schraub negatives, cs 39 2 Set construction; untitled Porter sculpture (aka"Wave"); computer lab; "Flying Weenies"poster 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Tennis, fencing; classroom 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Bike path; computers; costumes; sound system; 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Admissions special programs (2 pages) 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown family housing 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Student family apartments 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown Santa Cruz 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Special Collections, UCSC Library 1984 Lucas Stang negatives, cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Childcare center 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 East Field House; Crown College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Performing Arts; Oakes; Porter sculpture (The Wave) 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs Jack Schaar, professor of politics; Elena Baskin Visual Arts, printmaking studio; undergrad 39 3 chemistry; Computer engineering lab -

COLLEGE EIGHT FROSH WELCOME to UCSC Welcome to UC Santa Cruz and Congratulations! This Is a Very Exciting Time in Your Life As You Begin a New Phase of Learning

ENVIRONMENT SOCIETY COLLEGE EIGHT FROSH Welcome Week Guide 2014 Week Welcome COLLEGE EIGHT WELCOME TO UCSC Welcome to UC Santa Cruz and congratulations! This is a very exciting time in your life as you begin a new phase of learning. Every year students tell us that a key factor to their success is getting involved on campus and making a difference in their community. We hope you take advantage of this week to learn as much as possible about your new environment. Fall Welcome Week has been planned for you to learn about the academic resources, to become familiar with the campus, and to learn about the Santa Cruz community. Use this guide to learn about the many workshops/events taking place campus-wide during Fall Welcome Week. Notice that some events are MANDATORY. Your academic and social transition to UC Santa Cruz is extremely important to us. We consider you a partner in your academic and social success here. Therefore we expect you to actively participate in the many programs and services this first week and well beyond. So, start now and begin making connections! 1 WELCOME TO COLLEGE EIGHT Welcome to College Eight and UC Santa Cruz! There are a number of things you’ll need to accomplish during your first several days on campus. This Orientation Schedule is designed to help guide you. Use it to learn about the many workshops, orientations, office hours and events across campus during Welcome Week. If you need more information ask an Orientation Leader (OL), Programs Assistant (PA), Resident Assistant (RA) or a member of our college staff. -

2020-21 DOMESTIC EXCHANGE PROGRAM APPLICATION Note: the Last Day to Submit This Application to the Office of the Registrar Is Feb

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR Registrar, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 Phone (831) 459-4412 • FAX (831) 459-5051 [email protected] 2020-21 DOMESTIC EXCHANGE PROGRAM APPLICATION Note: The last day to submit this application to the Office of the Registrar is Feb. 22, 2020. After Feb. 22, 2020, contact [email protected] for assistance. For more information, see the Domestic Exchange Programs webpage. REQUESTOR Name (Last, First, Middle) _____________________________________________________________________________ Student ID __________________________________________ Birthdate ______________________________________ College ___________________________________________ Major ___________________________________________ Total credits (including this quarter) _____________________ ACADEMIC LEVEL Frosh Sophomore Junior Senior FINANCIAL AID I expect to receive UCSC financial aid during the exchange period. Yes No PREFERENCES University University of New Hampshire University of New Mexico Period 202020-21 Academic Year 202020 Fall Semester Only 202021 Spring Semester Only Please complete page 2 and the Proposed Course Study Plan beginning on page 3. Page 1 of 5 Revised: 11/27/2019 DIVISION OF UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION Rachel Carson College • Cowell College • Crown College • Kresge College • Merrill College • Oakes College • Porter College • Stevenson College Campus Orientation • Enrollment Management • Financial Aid and Scholarships • Office of the Registrar • Undergraduate Admissions Campus Advising Coordination • Educational Partnership Center • Office of the Vice Provost and Dean • Summer Session UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR Registrar, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 Phone (831) 459-4412 • FAX (831) 459-5051 [email protected] 2020-21 DOMESTIC EXCHANGE PROGRAM APPLICATION Note: The last day to submit this application to the Office of the Registrar is Feb. 22, 2020. -

University of California Santa Cruz Merrill Residence Halls Capital Renewal (Tiered from 2005 LRDP EIR) SCH #2012062017

Final Initial Study/ Proposed Mitigated Negative Declaration University of California Santa Cruz Merrill Residence Halls Capital Renewal (Tiered from 2005 LRDP EIR) SCH #2012062017 Prepared By: Office of Physical Planning & Construction University of California Santa Cruz 1156 High Street, Barn G Santa Cruz, CA 95064 November 2012 Contact: Alisa Klaus, Senior Environmental Planner (831) 459-3732 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Project Information ............................................................................................................ 1 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 2 2.1 Initial Study ........................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Public and Agency Review .................................................................................... 3 2.3 Project Approvals .................................................................................................. 3 2.4 Organization of the Initial Study ........................................................................... 3 3 Project Description ............................................................................................................ 5 3.1 Project Location ..................................................................................................... 5 3.2 Project Overview ................................................................................................... 8 3.3 Project -

UCSC Commencements Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt629021m1 No online items Inventory of the UCSC Commencements Collection UCSC OAC Unit The University Library Special Collections and Archives University Library University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, California, 95064 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucsc.edu/speccoll/ © 2005 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of the UCSC UA 32 1 Commencements Collection Inventory of the UCSC Commencements Collection Collection number: UA 32 The University Library University Archives University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, California Processed by: Special Collections & Archives Processing Staff Date Completed: December 2010, updated 2013 Encoded by: Special Collections & Archives Processing Staff © 2005 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: UCSC Commencements collection Dates: 1966- Collection number: UA 32 Collector: University of California, Santa Cruz Collection Size: 11 half cartons Repository: University of California, Santa Cruz. University Library. University Archives Santa Cruz, California 95064 Abstract: This collection contains various commencement programs, invitations, speeches, certificates, and some related correspondence. Physical location: Stored in Special Collections & Archives: Advance notice is required for access to the papers. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection open for research. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the University of California. Literary rights are retained by the creators of the records and their heirs. For permission to publish or to reproduce the material, please contact the Head of Special Collections and Archives. Preferred Citation UCSC Commencements collection. UA 32. University Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Acquisition Information Original collection transferred from Alumni Office in 1998. -

The Postmodern Condition: a Report on Knowledge

The Postlllodern Condition: A Report on Kno-wledge Jean-Fran�ois Lyotard Translation from the French by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi Foreword by Fredric Jameson Theory and History of Literature, Volume 10 £P Manchester University Press . .� � orip��?�;� l c.:�-•-"� t3o Thk book wu F �u rt�pport sur I� savoir, copyright© 1979 by Les Editions de Minuit. English translation and Foreword copyright© 1984 by the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Published in the United Kingdom by Manchester University Press. Oxford Road Manchester M13 9PL Printed in the United States of America. British LibruyCatalopaing in Publication Data Lyotard, jean-Fran�is The postmodem condition- (Theory and history of literature) 1. Knowledge, Theory of I. Title 11. La condition postmodeme. English Ill. Series 001 Z361 ISBN 0·7190-1454-9 ISBN o-7 1 90-1450-6 pbk. "Answering the Question : "What Is Postmodemism?" appears in this book counesy of the University of Wisconsin Press (English translation of this essay by Regis Durand copyright© 1983 by University of Wisconsin Press; the essay appears in lhab Hassan and Sally Hassan , eds., lnno11ation/R�no11ation !Madison: University of Wisconsin Press,198 3) ) and counesy of jean Piel, editor of Critiqu�. where the essay originally appeared as "Reponse a Ia question: qu'est-ce que le postmodc:rnc:?" in Critiqu�. number 419 (April 1982). Contents Foreword by Fredric jameson vii Introduction xxiii 1. The Field : Knowledge in Computerized Societies 3 2. The Problem : Legitimation 6 3. The Method: Language Games 9 4. The Nature of the Social Bond: The Modern Alternative 11 S. -

Where to Find Help Colleges at Ucsc Campus Hot Spots

WHERE TO FIND HELP CAMPUS HOT SPOTS Science Hill 7 Conference Offices College Ten Arboretum & Botanic Garden 1 The buildings on UCSC’s Science Hill include the College Nine Crown College There are Conference Offices in various locations award-winning Science and Engineering Library, The UCSC Arboretum & Botanic Garden is a set amid redwood trees and open to the public; on campus with friendly and knowledgeable staff to research and teaching facility serving the campus and assist you. Locations and hours are listed below: Sinsheimer Laboratories, housing the Biology 167 the public. Particular specialties are conifers, primitive Department; Thimann Laboratories, housing the North Perimeter angiosperms, and plant families of the Southern West Conference Office W Parking Lot Chemistry and Biochemistry Department; the 150 Hemisphere. Located near the intersection of Empire Earth and Marine Sciences Building, housing the Social Grade and Western Drive, the Arboretum is open to 7:00 am–8:00 pm Sciences 1 Earth and Planetary Sciences and Ocean Sciences 156 154 155 the public daily with an entrance fee of $5.00. Norrie’s Porter College Apt. E #104 RV * * Departments; and Natural Sciences 2, housing the Park Social 153 152 139 Sciences 2 Gift Shop is also open daily. arboretum.ucsc.edu Phone: (831) 502-7000 165 166 Firehouse Environmental Studies Department as well as the Serving: Rachel Carson, Oakes, Porter and Kresge 139 Center for Adaptive Optics. Access to Science Hill is 139 111 123 Merrill College ATMs 2 off McLaughlin Drive. oad University R 111 Engineering 2 n ** East Conference Office E 123 Center Bank ATMs, accepting most cards, are located just 164 8 111 139* Communications Co-gen quapi 111 across from the Bay Tree Bookstore.