UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2007 February

ARTICLE .1 Macro-Perspectives beyond the World System Joseph Voros Swinburne University of Technology Australia Abstract This paper continues a discussion begun in an earlier article on nesting macro-social perspectives to also consider and explore macro-perspectives beyond the level of the current world system and what insights they might reveal for the future of humankind. Key words: Macrohistory, Human expansion into space, Extra-terrestrial civilisations Introduction This paper continues a train of thought begun in an earlier paper (Voros 2006) where an approach to macro-social analysis based on the idea of "nesting" social-analytical perspectives was described and demonstrated (the essence of which, for convenience, is briefly summarised here). In that paper, essential use was made of a typology of social-analytical perspectives proposed by Johan Galtung (1997b), who suggested that human systems could be viewed or studied at three main levels of analysis: the level of the individual person; the level of social systems; and the level of world systems. Distinctions can be made between different foci of study. The focus may be on the stages and causes of change through time (termed diachronic), or it could be at some specific point in time (termed synchronic). As well, the focus may be on a specific single case (termed idiographic), in contrast to seeking regularities, patterns, or generalised "laws" (termed nomo- thetic). In this way, there are four main types of perspectives found at any particular level of analy- sis. This conception is shown here in slightly adapted form in Table 1.1 Journal of Futures Studies, February 2007, 11(3): 1 - 28 Journal of Futures Studies Table 1: Three Levels of Social Analysis Source: Adapted from Galtung (1997b). -

Carl Sagan's Groovy Cosmos

CARL SAGAN’S GROOVY COSMOS: PUBLIC SCIENCE AND AMERICAN COUNTERCULTURE IN THE 1970S By SEAN WARREN GILLERAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of History MAY 2017 © Copyright by SEAN WARREN GILLERAN, 2017 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by SEAN WARREN GILLERAN, 2017 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of SEAN WARREN GILLERAN find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. _________________________________ Matthew A. Sutton, Ph.D., Chair _________________________________ Jeffrey C. Sanders, Ph.D. _________________________________ Lawrence B. A. Hatter, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis has been years in the making and is the product of input from many, many different people. I am grateful for the support and suggestions of my committee—Matt Sutton, Jeff Sanders, and Lawrence Hatter—all of whom have been far too patient, kind, and helpful. I am also thankful for input I received from Michael Gordin at Princeton and Helen Anne Curry at Cambridge, both of whom read early drafts and proposals and both of whose suggestions I have been careful to incorporate. Catherine Connors and Carol Thomas at the University of Washington provided much early guidance, especially in terms of how and why such a curious topic could have real significance. Of course, none of this would have happened without the support of Bruce Hevly, who has been extraordinarily generous with his time and whose wonderful seminars and lectures have continued to inspire me, nor without Graham Haslam, who is the best teacher and the kindest man I have ever known. -

Qisar-Alexander-Ollongren-Astrolinguistics.Pdf

Astrolinguistics Alexander Ollongren Astrolinguistics Design of a Linguistic System for Interstellar Communication Based on Logic Alexander Ollongren Advanced Computer Science Leiden University Leiden The Netherlands ISBN 978-1-4614-5467-0 ISBN 978-1-4614-5468-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-5468-7 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2012945935 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, speci fi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on micro fi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied speci fi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the respective Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a speci fi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Cover Letter for KZSC Advisor Position I'm Writing to Apply for The

Cover Letter for KZSC Advisor Position I'm writing to apply for the job of KZSC advisor. With my passions, experience and skills, I think I would be a great fit for the job. I've worked in and around radio since I started on my college radio station, WEOS FM, as a freshman. I've hosted and produced shows and I've been a nationally-published radio columnist. I had the radio bug from the time I was young. I'm one of the rare breed who love the medium and always have. But I didn't choose it as a full time profession. Instead I focused on journalism and teaching, both of which gave me skills I would bring to UCSC. I've been a reporter and editor for three decades and a teacher for half that time. I worked at the Santa Cruz Mercury News for 22 years and was a radio writer for much of it. I studied the industry and wrote columns critiquing it. During that time I got to know many people at all levels of the business and appeared on media outlets from Howard Stern to Nightline. I've also taught broadcasting at Cabrillo and De Anza Colleges. I am currently the Chairman of the Journalism Department at Cabrillo, where I've gotten experience that would help at KZSC. I've dealt with hiring and firing; I've taught some 200 students a year; I've managed the department's budget; and I've been the advisor to the school's newspaper. I manage a radio course through the school where students produce a show on KSCO-AM in return for time as interns at the station. -

Season Announcement Press Release Final

For more information contact: Allie Magee / [email protected] / 314-775-7412 ST. LOUIS SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL RETURNS TO LIVE PERFORMANCE IN FOREST PARK WITH K I N G L E A R STARRING TONY, EMMY & GRAMMY WINNER ANDRÉ DE SHIELDS JUNE 2 - 27, 2021 PLUS FULL 2021 SEASON LINE UP St. Louis, MO (March 5, 2021) -- The St. Louis Shakespeare Festival (Tom Ridgely, Producing Artistic Director) announced today that Tony, Emmy and Grammy award-winner André De Shields (Broadway: Hadestown, The Wiz, Ain’t Misbehavin) will star in King Lear as part of its 21st summer of free Shakespeare in Forest Park. The production marks the theater’s return to live outdoor performance, one of the first scheduled in the country. King Lear will be directed by Carl Cofield (Associate Artistic Director of the Classical Theatre of Harlem) and begin on Wednesday, June 2, with an opening night set for Friday, June 4 at 8:00 pm, and play through June 27 to strictly limited capacity crowds. The Festival’s 2021 Season will also include a new outdoor touring production of Othello that will visit 24 public parks across the metro area and three outdoor performances of “Shakespeare in the Streets: The Ville” in one of the most historically significant Black communities in America. Also announced, the second Confluence New Play Festival and members of the third Regional Writers Cohort, and a six-month Directors Fellowship now accepting applications. “André is a national treasure and one of the most extraordinary theatrical artists alive,” said producing artistic director Tom Ridgely in a statement. -

Visionaries of the Visual

UC SANTA CRUZ Winter 2001 R E V I E W Visionaries ofthe Visual Ada Takahashi is one of the many UCSC alumni working as museum and gallery curators and directors Plus: Filling the teacher gap; Measuring mercury contamination CONTENTS FROM THE CHANCELLOR By M.R.C. Greenwood UC Santa Cruz Features Visionaries of the visual n my position as chancellor, challenge, launching a 15-month Review As curators or directors at I am fortunate indeed to come in program that provides our students Chancellor some of the country’s most contact with many of the people with both a teaching credential and M.R.C. Greenwood Visionaries of the Visual 8 respected art museums that make the UC Santa Cruz master’s degree in education. and galleries, a number of II Vice Chancellor, University Relations community so special: our students, Our faculty and students are Ronald P. Suduiko UCSC graduates are helping whose thirst for knowledge is only achieving distinction in a variety of decide which works their Associate Vice Chancellor, Meeting the Need 14 exceeded by their commitment to other ways. Research that is revealing Communications institutions buy or borrow— improve society; our faculty and staff, important information about mercury Elizabeth Irwin and ultimately bring to who diligently see to it that our students contamination in San Francisco Bay Editor freidman/losgary angeles times the public’s attention. 8 receive a world-class education at the waters is one example of that excel- Mercury: A Toxic Legacy 18 Jim Burns Meeting the need same time that UCSC produces impres- lence (page 18). -

Why SETI Will Fail ‡

Why SETI Will Fail z B. Zuckerman1 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The union of space telescopes and interstellar spaceships guarantees that if extraterrestrial civilizations were common, someone would have come here long ago. PACS numbers: 97.10.Tk arXiv:1912.08386v1 [physics.pop-ph] 18 Dec 2019 z This article originally appeared in the September/October 2002 issue of Mercury magazine (published by the Astronomical Society of the Pacific). Why SETI Will Fail 2 1. Introduction Where do humans stand on the scale of cosmic intelligence? For most people, this question ranks at or very near the top of the list of "scientific things I would like to know." Lacking hard evidence to constrain the imagination, optimists conclude that technological civilizations far in advance of our own are common in our Milky Way Galaxy, whereas pessimists argue that we Earthlings probably have the most advanced technology around. Consequently, this topic has been debated endlessly and in numerous venues. Unfortunately, significant new information or ideas that can point us in the right direction come along infrequently. But recently I have realized that important connections exist between space astronomy and space travel that have never been discussed in the scientific or popular literature. These connections clearly favor the more pessimistic scenario mentioned above. Serious radio searches for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) have been conducted during the past few decades. Brilliant scientists have been associated with SETI, starting with pioneers like Frank Drake and the late Carl Sagan and then continuing with Paul Horowitz, Jill Tarter, and the late Barney Oliver. -

Astronomy Beat

ASTRONOMY BEAT ASTRONOMY BEAT /VNCFSt"QSJM XXXBTUSPTPDJFUZPSH 1VCMJTIFS"TUSPOPNJDBM4PDJFUZPGUIF1BDJöD &EJUPS"OESFX'SBLOPJ ª "TUSPOPNJDBM 4PDJFUZ PG UIF 1BDJöD %FTJHOFS-FTMJF1SPVEöU "TIUPO"WFOVF 4BO'SBODJTDP $" The Origin of the Drake Equation Frank Drake Dava Sobel Editor’s Introduction Most beginning classes in astronomy introduce their students to the Drake Equation, a way of summarizing our knowledge about the chances that there is intelli- ASTRONOMYgent life among the stars with which we humans might BEAT communicate. But how and why did this summary for- mula get put together? In this adaptation from a book he wrote some years ago with acclaimed science writer Dava Sobel, astronomer and former ASP President Frank Drake tells us the story behind one of the most famous teaching aids in astronomy. ore than a year a!er I was done with Proj- 'SBOL%SBLFXJUIUIF%SBLF&RVBUJPO 4FUI4IPTUBL 4&5**OTUJUVUF ect Ozma, the "rst experiment to search for radio signals from extraterrestrial civiliza- Mtions, I got a call one summer day in 1961 from a man to be invited. I had never met. His name was J. Peter Pearman, and Right then, having only just met over the telephone, we he was a sta# o$cer on the Space Science Board of the immediately began planning the date and other details. National Academy of Science… He’d followed Project We put our heads together to name every scientist we Ozma throughout, and had since been trying to build knew who was even thinking about searching for ex- support in the government for the possibility of dis- traterrestrial life in 1961. -

The UC Santa Cruz Budget – a Bird's Eye View

Office of Planning and Budget 2012-13 Edition The UC Santa Cruz Budget – A Bird’s Eye View Message from Office of Planning and Budget… December 2012 On behalf of the staff in Planning and Budget, I am happy to provide you with the 2012-13 edition of The Those birds have a good view of the budget. Birds Eye View. This document provides a unique look at the permanent operating budget for the campus and each of its major units. It includes recent data on the degrees conferred, the majors of our students, the number of faculty budgeted in each department, enrollments by department, and extramural awards. You can find it on the web at http://planning.ucsc.edu/budget/reports/birdseye. UCSC has implemented cuts in each of the past five years. While the cuts have been primarily in the core-funded areas, the impact has been felt throughout the campus. The passage of Proposition 30—and steps taken by the UC Office of the President to renew discussions with the State concerning the longer term funding needs of the University—represents the prospect for California to put public higher education back on a pathway toward fiscal stability. If the State and the UC Regents each agree on a multi-year financial plan for UC, this will create an opportunity for UCSC to create our own multi-year path. While additional cuts will be needed in 2013-14 to address the budget shortfall from 2012-13, we are cautiously optimistic that we can begin to plan for more budget stability. -

How Will You Build Your Legacy? CONTENTS Your Support Builds on Our Achievements

UCSC GUIDE TO PLANNED GIVING How will you build your legacy? CONTENTS YOUR SUPPORT BUILDS ON OUR ACHIEVEMENTS: YOU CAN BUILD A STRONG LEGACY ............3 • UC Santa Cruz researchers were the first to assemble A note from Chancellor Blumenthal the DNA sequence of the human genome and gave the world a free, revolutionary tool, the UCSC YOUR GIFT IS A POWERFUL INVESTMENT .. 4 Genome Browser. Researchers worldwide use the genome browser to discover new ways to diagnose, STUDENT STORIES ......................................... 5 treat and even prevent diseases. STEP 1 YOUR GIFT IS A REWARDING INVESTMENT .. 7 • UCSC researchers saved the peregrine falcon from near extinction. Today, their numbers are soaring. Planned Giving: Something for Everyone Commemorative Gifts Current or Endowed Gifts? • Through research, education, and public service pro- A Social Investment grams, UCSC has transformed the way food is grown and helped make “sustainability” a household word. STEP 2 HOW TO BEGIN YOUR LEGACY .....................8 Cash Gifts • The Dickens Project at UC Santa Cruz is internationally Property Other than Cash recognized as the premier center for Dickens studies Appreciated Securities in the world and is one of the leading sites for research Real Estate on 19th-century British culture. Tangible Personal Property .............................9 Life Insurance ....................................................9 • The first AIDS vaccine to have shown effectiveness STEP 3 against the AIDS virus was developed by UC Santa MAKE YOUR GIFT WORK -

UA 128 Inventory Photographer Neg Slide Cs Series 8 16

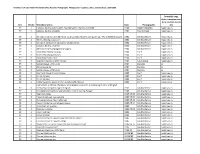

Inventory: UA 128, Public Information Office Records: Photographs. Photographer negatives, slides, contact sheets, 1980-2005 Format(s): negs, slides, transparencies (trn), contact sheets Box Binder Title/Description Date Photographer (cs) 39 1 Campus, faculty and students. Marketing firm: Barton and Gillet. 1980 Robert Llewellyn negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Paul Schraub negatives, cs 39 2 Set construction; untitled Porter sculpture (aka"Wave"); computer lab; "Flying Weenies"poster 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Tennis, fencing; classroom 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Bike path; computers; costumes; sound system; 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Admissions special programs (2 pages) 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown family housing 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Student family apartments 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown Santa Cruz 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Special Collections, UCSC Library 1984 Lucas Stang negatives, cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Childcare center 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 East Field House; Crown College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Performing Arts; Oakes; Porter sculpture (The Wave) 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs Jack Schaar, professor of politics; Elena Baskin Visual Arts, printmaking studio; undergrad 39 3 chemistry; Computer engineering lab -

Group Sales Tickets

SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY 21st Annual Table of Contents D.C.’s favorite Feature Letter from Michael Kahn 5 The Two Faces of Capital summer by Drew Lichtenberg 6 Program Synopsis 11 theatre event About the Playwright 13 Title Page 15 Cast 17 is back! Cast Biographies 18 PRESENTED BY Direction and Design Biographies 22 Shakespeare Theatre Company Tickets will be available Board of Trustees 8 online and in line! Shakespeare Theatre Company 26 Individual Support 28 Visit ShakespeareTheatre.org/FFA for more details on how to get your tickets via lottery Corporate Support 40 or at Sidney Harman Hall on the day of the Foundation and performance. Tickets for 2011–2012 Season Government Support 41 subscribers available through the Box Office Academy for Classical Acting 41 beginning July 5, 2011, at 10 a.m. For the Shakespeare Theatre Company 42 Join the Friends of Free Staff 44 JULIUS For All for tickets! Audience Services 50 Free For All would not be possible without Creative Conversations 50 CAESAR the hundreds of individuals who generously donate to support the program each year. “ Only with the help of the Friends of Free For All is STC able to offer free performances, All hail Julius Caesar! making Shakespeare accessible to … One of the best productions of this or any season.” Washington, D.C., area residents every summer. The Washingtonian In appreciation for this support, Friends of Free For All receive exclusive benefits during This Year's Production: the festival such as reserved Free For All tickets, the option to have tickets mailed in August 18–September 4 advance, special event invitations, program recognition and more.