Incipient Non-Adaptive Radiation by Founder Effect? Oliarus Polyphemus Fennah, 1973 – a Subterranean Model Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrestrial Isopods from the Hawaiian Islands (Isopoda: Oniscidea)1

59 Terrestrial Isopods from the Hawaiian Islands (Isopoda: Oniscidea)1 STEFANO TAITI (Centro di Studio per la Faunistica ed Ecologia Tropicali del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Via Romana 17, 50125 Firenze, Italy) and FRANCIS G. HOWARTH (Hawaii Biological Survey, Bishop Museum, PO Box 19000, Honolulu, Hawaii 96817, USA) The following are notable new distribution records for terrestrial isopods in Hawaii. Four species are newly recorded from the state, and many new island records are given for other species, especially for the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, where only one species (Porcellionides pruinosus [Brandt]) was previously known. All included records are based on specimens deposited in Bishop Museum. Taiti & Ferrara (1991) presented new distribution records and taxonomic information on 27 species and provided an overview of the terrestrial isopod fauna of the Hawaiian Islands, and Nishida (1994) list- ed all species recorded from the islands together with the island distributions of each. We call special attention to the several endemic armadillid pillbugs that have not been recollected in more than 60 years. These are Hawaiodillo danae (Dollfus) and H. sharpi (Dollfus) from Kauai, H. perkinsi (Dollfus) from Maui, Spherillo albospinosus (Dollfus) from Oahu, and S. carinulatus Budde-Lund from Kauai. In addition, S. hawai- ensis Dana, previously recorded from Kauai, Oahu, Molokai, and Lanai was last collected on the main islands in 1933 on Oahu although it appears to be still common on Nihoa. We fear some species in this complex may be extinct and encourage field biologists to watch for them in potential refugia. For economy of space, the following abbreviations are used for collectors listed be- low: DJP = David J. -

Pu'u Wa'awa'a Biological Assessment

PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A, NORTH KONA, HAWAII Prepared by: Jon G. Giffin Forestry & Wildlife Manager August 2003 STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF FORESTRY AND WILDLIFE TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE ................................................................................................................................. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. ii GENERAL SETTING...................................................................................................................1 Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Land Use Practices...............................................................................................................1 Geology..................................................................................................................................3 Lava Flows............................................................................................................................5 Lava Tubes ...........................................................................................................................5 Cinder Cones ........................................................................................................................7 Soils .......................................................................................................................................9 -

Spider Biodiversity Patterns and Their Conservation in the Azorean

Systematics and Biodiversity 6 (2): 249–282 Issued 6 June 2008 doi:10.1017/S1477200008002648 Printed in the United Kingdom C The Natural History Museum ∗ Paulo A.V. Borges1 & Joerg Wunderlich2 Spider biodiversity patterns and their 1Azorean Biodiversity Group, Departamento de Ciˆencias conservation in the Azorean archipelago, Agr´arias, CITA-A, Universidade dos Ac¸ores. Campus de Angra, with descriptions of new species Terra-Ch˜a; Angra do Hero´ısmo – 9700-851 – Terceira (Ac¸ores); Portugal. Email: [email protected] 2Oberer H¨auselbergweg 24, Abstract In this contribution, we report on patterns of spider species diversity of 69493 Hirschberg, Germany. the Azores, based on recently standardised sampling protocols in different hab- Email: joergwunderlich@ t-online.de itats of this geologically young and isolated volcanic archipelago. A total of 122 species is investigated, including eight new species, eight new records for the submitted December 2005 Azorean islands and 61 previously known species, with 131 new records for indi- accepted November 2006 vidual islands. Biodiversity patterns are investigated, namely patterns of range size distribution for endemics and non-endemics, habitat distribution patterns, island similarity in species composition and the estimation of species richness for the Azores. Newly described species are: Oonopidae – Orchestina furcillata Wunderlich; Linyphiidae: Linyphiinae – Porrhomma borgesi Wunderlich; Turinyphia cavernicola Wunderlich; Linyphiidae: Micronetinae – Agyneta depigmentata Wunderlich; Linyph- iidae: -

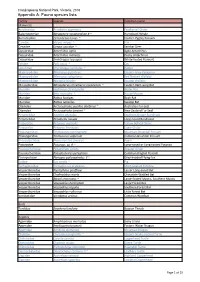

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus -

Faunistic Survey of Terrestrial Isopods (Isopoda: Oniscidea) in the Boč Massif Area

NATURA SLOVENIAE 16(1): 5-14 Prejeto / Received: 5.2.2014 SCIENTIFIC PAPER Sprejeto / Accepted: 19.5.2014 Faunistic survey of terrestrial isopods (Isopoda: Oniscidea) in the Boč Massif area Blanka RAVNJAK & Ivan KOS Department of Biology, Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana, Večna pot 111, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. In 2005, terrestrial isopods were sampled in the Boč Massif area, eastern Slovenia, and their fauna compared at five different sampling sites: forest on dolomite, forest on limestone, thermophilous forest, young stage forest and extensive meadow. Two sampling methods were used: hand collecting and quadrate soil sampling with a subsequent heat extraction of animals. The highest species diversity (8 species) was recorded in the forest on dolomite and in young stage forest. No isopod species were found in samples from the extensive meadow. In the entire study area we recorded 12 different terrestrial isopod species and caught 109 specimens in total. The research brought new data on the distribution of two quite poorly known species in Slovenia: the Trachelipus razzauti and Haplophthalmus abbreviatus. Key words: species structure, terrestrial isopods, Boč Massif, Slovenia Izvleček. Favnistični pregled mokric (Isopoda: Oniscidea) na območju Boškega masiva – Leta 2005 smo na območju Boškega masiva v vzhodni Sloveniji opravili vzorčenje favne mokric. V raziskavi smo primerjali favno mokric na petih različnih vzorčnih mestih: v gozdu na dolomitu, v gozdu na apnencu, termofilnem gozdu, mladem gozdu in na ekstenzivnem travniku. Vzorčili smo z dvema metodama, in sicer z metodo ročnega pobiranja ter z odvzemom talnih vzorcev po metodi kvadratov. -

Woodlice in Britain and Ireland: Distribution and Habitat Is out of Date Very Quickly, and That They Will Soon Be Writing the Second Edition

• • • • • • I att,AZ /• •• 21 - • '11 n4I3 - • v., -hi / NT I- r Arty 1 4' I, • • I • A • • • Printed in Great Britain by Lavenham Press NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS ISBN 0 904282 85 6 COVER ILLUSTRATIONS Top left: Armadillidium depressum Top right: Philoscia muscorum Bottom left: Androniscus dentiger Bottom right: Porcellio scaber (2 colour forms) The photographs are reproduced by kind permission of R E Jones/Frank Lane The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) was established in 1973, from the former Nature Conservancy's research stations and staff, joined later by the Institute of Tree Biology and the Culture Centre of Algae and Protozoa. ITE contributes to, and draws upon, the collective knowledge of the 13 sister institutes which make up the Natural Environment Research Council, spanning all the environmental sciences. The Institute studies the factors determining the structure, composition and processes of land and freshwater systems, and of individual plant and animal species. It is developing a sounder scientific basis for predicting and modelling environmental trends arising from natural or man- made change. The results of this research are available to those responsible for the protection, management and wise use of our natural resources. One quarter of ITE's work is research commissioned by customers, such as the Department of Environment, the European Economic Community, the Nature Conservancy Council and the Overseas Development Administration. The remainder is fundamental research supported by NERC. ITE's expertise is widely used by international organizations in overseas projects and programmes of research. -

Aphids (Hemiptera, Aphididae)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal BioRisk 4(1): 435–474 (2010) Aphids (Hemiptera, Aphididae). Chapter 9.2 435 doi: 10.3897/biorisk.4.57 RESEARCH ARTICLE BioRisk www.pensoftonline.net/biorisk Aphids (Hemiptera, Aphididae) Chapter 9.2 Armelle Cœur d’acier1, Nicolas Pérez Hidalgo2, Olivera Petrović-Obradović3 1 INRA, UMR CBGP (INRA / IRD / Cirad / Montpellier SupAgro), Campus International de Baillarguet, CS 30016, F-34988 Montferrier-sur-Lez, France 2 Universidad de León, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Universidad de León, 24071 – León, Spain 3 University of Belgrade, Faculty of Agriculture, Nemanjina 6, SER-11000, Belgrade, Serbia Corresponding authors: Armelle Cœur d’acier ([email protected]), Nicolas Pérez Hidalgo (nperh@unile- on.es), Olivera Petrović-Obradović ([email protected]) Academic editor: David Roy | Received 1 March 2010 | Accepted 24 May 2010 | Published 6 July 2010 Citation: Cœur d’acier A (2010) Aphids (Hemiptera, Aphididae). Chapter 9.2. In: Roques A et al. (Eds) Alien terrestrial arthropods of Europe. BioRisk 4(1): 435–474. doi: 10.3897/biorisk.4.57 Abstract Our study aimed at providing a comprehensive list of Aphididae alien to Europe. A total of 98 species originating from other continents have established so far in Europe, to which we add 4 cosmopolitan spe- cies of uncertain origin (cryptogenic). Th e 102 alien species of Aphididae established in Europe belong to 12 diff erent subfamilies, fi ve of them contributing by more than 5 species to the alien fauna. Most alien aphids originate from temperate regions of the world. Th ere was no signifi cant variation in the geographic origin of the alien aphids over time. -

Phragmites Australis

Journal of Ecology 2017, 105, 1123–1162 doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12797 BIOLOGICAL FLORA OF THE BRITISH ISLES* No. 283 List Vasc. PI. Br. Isles (1992) no. 153, 64,1 Biological Flora of the British Isles: Phragmites australis Jasmin G. Packer†,1,2,3, Laura A. Meyerson4, Hana Skalov a5, Petr Pysek 5,6,7 and Christoph Kueffer3,7 1Environment Institute, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; 3Institute of Integrative Biology, Department of Environmental Systems Science, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich, CH-8092, Zurich,€ Switzerland; 4University of Rhode Island, Natural Resources Science, Kingston, RI 02881, USA; 5Institute of Botany, Department of Invasion Ecology, The Czech Academy of Sciences, CZ-25243, Pruhonice, Czech Republic; 6Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, CZ-12844, Prague 2, Czech Republic; and 7Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Matieland 7602, South Africa Summary 1. This account presents comprehensive information on the biology of Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. (P. communis Trin.; common reed) that is relevant to understanding its ecological char- acteristics and behaviour. The main topics are presented within the standard framework of the Biologi- cal Flora of the British Isles: distribution, habitat, communities, responses to biotic factors and to the abiotic environment, plant structure and physiology, phenology, floral and seed characters, herbivores and diseases, as well as history including invasive spread in other regions, and conservation. 2. Phragmites australis is a cosmopolitan species native to the British flora and widespread in lowland habitats throughout, from the Shetland archipelago to southern England. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

Flies) Benjamin Kongyeli Badii

Chapter Phylogeny and Functional Morphology of Diptera (Flies) Benjamin Kongyeli Badii Abstract The order Diptera includes all true flies. Members of this order are the most ecologically diverse and probably have a greater economic impact on humans than any other group of insects. The application of explicit methods of phylogenetic and morphological analysis has revealed weaknesses in the traditional classification of dipteran insects, but little progress has been made to achieve a robust, stable clas- sification that reflects evolutionary relationships and morphological adaptations for a more precise understanding of their developmental biology and behavioral ecol- ogy. The current status of Diptera phylogenetics is reviewed in this chapter. Also, key aspects of the morphology of the different life stages of the flies, particularly characters useful for taxonomic purposes and for an understanding of the group’s biology have been described with an emphasis on newer contributions and progress in understanding this important group of insects. Keywords: Tephritoidea, Diptera flies, Nematocera, Brachycera metamorphosis, larva 1. Introduction Phylogeny refers to the evolutionary history of a taxonomic group of organisms. Phylogeny is essential in understanding the biodiversity, genetics, evolution, and ecology among groups of organisms [1, 2]. Functional morphology involves the study of the relationships between the structure of an organism and the function of the various parts of an organism. The old adage “form follows function” is a guiding principle of functional morphology. It helps in understanding the ways in which body structures can be used to produce a wide variety of different behaviors, including moving, feeding, fighting, and reproducing. It thus, integrates concepts from physiology, evolution, anatomy and development, and synthesizes the diverse ways that biological and physical factors interact in the lives of organisms [3]. -

Diptera: Cyclorrhapha)

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Mitochondrial Genomes Provide Insights into the Phylogeny of Lauxanioidea (Diptera: Cyclorrhapha) Xuankun Li 1,†, Wenliang Li 2,†, Shuangmei Ding 1, Stephen L. Cameron 3, Meng Mao 4, Li Shi 5,* and Ding Yang 1,* 1 Department of Entomology, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (S.D.) 2 College of Forestry, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang 471023, China; [email protected] 3 Department of Entomology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Plant and Environmental Protection Science, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA; [email protected] 5 College of Agronomy, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot 010018, China * Correspondences: [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (D.Y.); Tel.: +86-471-431-7421 (L.S.); +86-10-6273-2999 (D.Y.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Academic Editor: Kun Yan Zhu Received: 26 January 2017; Accepted: 1 April 2017; Published: 14 April 2017 Abstract: The superfamily Lauxanioidea is a significant dipteran clade including over 2500 known species in three families: Lauxaniidae, Celyphidae and Chamaemyiidae. We sequenced the first five (three complete and two partial) lauxanioid mitochondrial (mt) genomes, and used them to reconstruct the phylogeny of this group. The lauxanioid mt genomes are typical of the Diptera, containing all 37 genes usually present in bilaterian animals. A total of three conserved intergenic sequences have been reported across the Cyclorrhapha. The inferred secondary structure of 22 tRNAs suggested five substitution patterns among the Cyclorrhapha. -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying