Next Strategy INAUGURAL LECTURE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Van Tekst

In het land der blinden Willem Oltmans bron Willem Oltmans, In het land der blinden. Papieren tijger, Breda 2001 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/oltm003inhe01_01/colofon.php © 2015 dbnl / Willem Oltmans Stichting 2 voor Jozias van Aartsen Willem Oltmans, In het land der blinden 7 1 Start Op 10 augustus 1953 besteeg ik voor het eerst de lange trappen naar de bovenste verdieping van het gebouw van het Algemeen Handelsblad aan de Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal in Amsterdam om mijn leven als journalist te beginnen. Chef van de redactie buitenland was dr. Anton Constandse. Van 1946 tot en met 1948 had ik de opleiding voor de diplomatieke dienst gevolgd van het Nederlands Opleidings Instituut voor het Buitenland (NOIB) op Nijenrode. Van 1948 tot en met 1950 volgde ik op het Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, de studie Political Science and International Relations. Inmiddels 25 jaar geworden twijfelde ik steeds meer aan een leven als ambtenaar van het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken. Was ik niet een te vrijgevochten en te zelfstandig denkende vogel om zonder tegensputteren of mokken braaf Haagse opdrachten uit te voeren waar ik het wellicht faliekant mee oneens zou zijn? Van een dergelijke incompatibilité d'humeurs zou immers alleen maar gedonder kunnen komen. Op het Yale College had ik in dit verband al het een en ander meegemaakt. In 1949 was ik tot praeses van de Yale International Club gekozen, een organisatie voor de in New Haven studerende buitenlandse studenten. Nederland knokte in die dagen onder de noemer van ‘politionele acties’ tegen Indonesië. Ik nodigde ambassadeur F.C.A. -

Chapter 36 Netherlands: the Pedophile Kingdom and Sodom and Gomorrah of the Modern World Joachim Hagopian

Chapter 36 Netherlands: The Pedophile Kingdom and Sodom and Gomorrah of the Modern World Joachim Hagopian Cover Credit: Nora Maccoby with permission http://www.noramaccoby.com/ The lineage of former Holy Roman and French nobility comprises today’s House of Orange-Nassau ruling over the constitutional monarchy of the Netherlands. The Dutch royalty owns major multinational corporations such as Royal Dutch Shell, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, Philips Electronics and Holland-America Line.1 The royal family has evolved its interests as a high-level authority currently operating as a branch of the Vatican’s Roman empire, wielding considerable influence over such powerful entities as the Rand Corporation, Koch Industries, Princeton University (founded in honor of the House of Orange), some of the world’s largest banks including AMRO and investment firms like BlackRock,2 the largest financial asset management institution on the planet, worth an estimated $7.4 trillion in client assets.3 Coincided by design with the planned Corona scamdemic, this year BlackRock’s been busily bailing out the US Federal Reserve, buying billions worth of bonds to keep the house of cards economy from imploding, in one fell swoop in April seizing control over the US Treasury and Federal Reserve.4 This private, unelected monolith has monopoly control now over the entire US economy as the centralized economic chokehold over the global masses prepares to tighten its death grip noose over humanity.5 As the long planned implosion of the world economy goes up in smoke, by engineered design, this latest power grab amidst the so called pandemic crisis is all about consolidation of power and control into fewer and fewer hands, lending new meaning to the thoroughly bankrupted USA Corporation owned and operated by the financial juggernaut of “the Crown.”6 The stakes have never been higher in 2020. -

Annemie Turtelboom

Aan: De Belgische Staat, namens deze gelijktijdig gericht aan: - Annemie Turtelboom, als verantwoordelijk Minister van Justitie [email protected], [email protected] - Karel DE GUCHT, Europees Commissaris van Handel en Minister van Staat; [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------ A.M.L. van Rooij heeft op 21 april 2010 als politiek vluchteling Nederland moeten verlaten om door toedoen van burgemeester P.M. Maas van Sint-Oedenrode in Nederland niet te worden vermoord in navolging van Pim Fortuyn. De daadwerkelijke veroorzaker is Cees van Rossum. A.M.L. van Rooij heeft om die reden mede namens J.E.M. van Rooij van Nunen bij aangetekende brief d.d. 6 mei 2010, aangevuld bij brief d.d. 26 mei 2010, politiek asiel aangevraagd bij Joëlle Milquet, Belgisch Vice- Eerste Minister en Minister van Werk en Gelijke Kansen, belast met het Migratie - en asielbeleid om in Sint-Oedenrode niet te worden vermoord. Zonhoven 10 juni 2013 Geachte - Annemie Turtelboom, als verantwoordelijk Minister van Justitie; - Karel De Gucht, als Europees Commissaris van Handel en Minister van Staat; Allereerst willen wij u beiden bedanken voor het feit dat geen enkel bestuurslid van het partijbestuur van de Open-VLD, waaronder u beiden, heeft gereageerd op ons bij e-mail van 5 juni 2013 verzonden sommatieverzoek om daarop vóór uiterlijk 7 juni 2013 te reageren. Betreffend sommatieverzoek (met deeplinks aan feitelijke onderbouw) vindt u om die reden dan nogmaals bijgevoegd in de volgende link: http://www.mstsnl.net/ekc/pdf/5-juni-2013-aanvullend-verzoekschrift-aan-landelijk- partijbestuur-open-vld-in-belgie.pdf Dit betekent dat het partijbestuur van de Open-VLD u beiden niet uit de partij heeft gezet omdat u beiden als Minister van Justitie en Minister van Staat overeenkomstig de formule die werd vastgelegd op 19 juli 1831 tegenover Koning Albert II de volgende ambtseed heeft afgelegd: Ik zweer getrouwheid aan de Koning, gehoorzaamheid aan de Grondwet en aan de wetten van het Belgische volk. -

Verstuurd Per Fax 070 – 3813999 En Per E-Mail: [email protected] En Per E-Mail: [email protected]

Verstuurd per fax 070 – 3813999 en per e-mail: [email protected] en per e-mail: [email protected] Aan: College van Beroep voor het bedrijfsleven t.a.v. de Wrakingskamer bestaande uit: - mr. E.R. Eggeraat; - mr. E. Dijt; - mr. M.M. Smorenburg Postbus 20021, 2500 EA Den Haag België: 22 februari 2012 Uw procedurenummer: AWB 11/443 S2 Ons kenmerk: DR/060611/B Betreft: Camping en Pensionstal Dommeldal V.O.F. als A.M.L. van Rooij en J.E.M. van Rooij van Nunen (cliënten)/ - Wraking van de rechters mr. E.R. Eggeraat, mr. E. Dijt, mr. M.M. Smorenburg (wrakingskamer) van het College van Beroep voor het bedrijfsleven in de zaak met als nummer AWB 11/443 S2 vóór de behandeling ter zitting op 23 februari 2012 om 15.00 uur. Geachte behandelend rechters mr. E.R. Eggeraat, mr. E. Dijt en mr. M.M. Smorenburg van de wrakingskamer, Mede namens de vennoten A.M.L. van Rooij (vanaf 22 april 2010 in België wonend om door toedoen van burgemeester P.M. Maas en zijn CDA niet vermoord te worden) en J.E.M. van Rooij van Nunen van Camping en Pensionstal Dommeldal VOF., gevestigd op ’t Achterom 9-9A, 5491 XD Sint- Oedenrode en A.M.L van Rooij en J.E.M van Rooij van Nunen als natuurlijk persoon, wraakt ondergetekende hierbij de behandelend rechters mr. E.R. Eggeraat, mr. E. Dijt, mr. M.M. Smorenburg van de wrakingskamer in de zaak met als nummer: AWB 11/443 S2 vóór de behandeling ter zitting op 23 februari 2012 om 15.00 uur op grond van ondergenoemde feiten en omstandigheden: Ingevolge artikel 8:15 Algemene wet bestuursrecht kan op verzoek van een partij elk van de rechters die een zaak behandelen, worden gewraakt op grond van feiten of omstandigheden waardoor de rechterlijke onpartijdigheid schade zou kunnen leiden. -

Small Country, Big Player

Small country, big player The Netherlands and synthetic drugs over the past 50 years Small country, big player The Netherlands and synthetic drugs over the past 50 years Pieter Tops Judith van Valkenhoef Edward van der Torre Luuk van Spijk Politieacademie Apeldoorn 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 6 1.1 Central questions 7 1.2 Perspective 8 1.3 Structure of the document 9 2 A synthetic drugs network in action 11 2.1 The network’s working method 11 2.2 The preparations: chemicals, hardware and locations 16 2.3 The production 20 2.4 The aftermath: cleaning up and distribution 23 3 The unprecedented scope of the world of synthetic drugs 27 3.1 Limited information 28 3.2 What is available? 30 3.3 Early-stage seizures 31 3.4 Seizure rate 33 3.5 The wholesale turnover 35 3.6 Trade Proceeds 36 3.7 Share of Dutch criminals 39 3.8 Conclusion 40 4 A brief history of ecstasy and amphetamine in the Netherlands 42 4.1 ‘The King of Speed’: the emergence of amphetamine 42 4.2 Can you feel it?!: the emergence of ecstasy 44 4.3 The Netherlands as a source country 47 4.4 Intensifying the action 49 4.5 Meanwhile in synthetic drugs circles 58 4.6 The Netherlands Police: further fragmentation 60 4.7 Conclusion 63 5 The original Brabant-Limburg synthetic drugs criminals 65 5.1 From brute force to synthetic drugs 65 5.2 From small-time criminals to top criminals 70 5.3 Conclusion 81 Small country, Big Player 4 Contents 6 The national and international arenas 82 6.1 The United Nations conventions 83 6.2 The EU precursor regulations 85 6.3 Three arenas 89 6.4 The -

Geachte Redacties Van De Volgende Nieuwe Media

DE GROENEN Datum: 15 januari 2012 Afgegeven met ontvangstbevestiging Uw kenmerk: 840000-12 Aan Arrondissementsparket ’s-Hertogenbosch Leeghwaterlaan 8, 5223 BA ’s-Hertogenbosch t.a.v. zaakcoördinator Mw. C. Bergman Betreft: Aanvullende strafaangifte op de door burgemeester Peter Maas (CDA) van Sint-Oedenrode gedane strafaangifte van smaad tegen de Politieke partij De Groenen en A.M.L. van Rooij als lijsttrekker van de Groenen Geachte mevrouw Overeenkomstig hetgeen ik met mevrouw L. van der Heijden heb afgesproken laat ik u hierbij onze aanvullende strafaangifte op de door burgemeester Peter Maas (CDA) van Sint-Oedenrode gedane strafaangifte van smaad tegen de Politieke partij De Groenen en A.M.L. van Rooij als lijsttrekker van de Groenen toekomen. Voor de inhoud van deze aanvullende strafaangifte verwijzen wij u naar de inhoud van ons verzoekschrift d.d. 11 januari 2011 tot opschorting van de behandeling ter zitting op 27 januari 2012 aan het college van beroep voor het besdrijfsleven te Den Haag in de zaak met als procedurenummer: AWB 11/443 S2, bestaande uit 83 pagina’s met de volgende 20-tal bijlagen aan bewijsstukken: 1. brief d.d. 28 december 2009 van Philips advocaat Dries Duynstee aan UWV Amsterdam waarin hij over de arbeidsongeschiktheid van A.M.L. van Rooij valsheid in geschrift heeft gepleegd (2 blz); 2. Parttime arbeidscontract d.d. 6 maart 1998 van Philips Medical Systems Nederland B.V. met A.M.L. van Rooij (2 blz); 3. inschrijving KvK Van Rooij Holding B.V. dossiernummer: 17102683 (2 blz); 4. inschrijving KvK Ecologisch Kennis Centrum B.V. dossiernummer: 16090111 (2 blz); 5. -

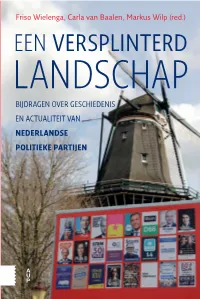

Een Versplinterd Landschap Belicht Deze Historische Lijn Voor Alle Politieke NEDERLANDSE Partijen Die in 2017 in De Tweede Kamer Zijn Gekozen

Markus Wilp (red.) Wilp Markus Wielenga, CarlaFriso vanBaalen, Friso Wielenga, Carla van Baalen, Markus Wilp (red.) Het Nederlandse politieke landschap werd van oudsher gedomineerd door drie stromingen: christendemocraten, liberalen en sociaaldemocraten. Lange tijd toonden verkiezingsuitslagen een hoge mate van continuïteit. Daar kwam aan het eind van de jaren zestig van de 20e eeuw verandering in. Vanaf 1994 zette deze ontwikkeling door en sindsdien laten verkiezingen EEN VERSPLINTERD steeds grote verschuivingen zien. Met de opkomst van populistische stromingen, vanaf 2002, is bovendien het politieke landschap ingrijpend veranderd. De snelle veranderingen in het partijenspectrum zorgen voor een over belichting van de verschillen tussen ‘toen’ en ‘nu’. Bij oppervlakkige beschouwing staat de instabiliteit van vandaag tegenover de gestolde LANDSCHAP onbeweeglijkheid van het verleden. Een dergelijk beeld is echter een ver simpeling, want ook in vroeger jaren konden de politieke spanningen BIJDRAGEN OVER GESCHIEDENIS hoog oplopen en kwamen kabinetten regelmatig voortijdig ten val. Er is EEN niet alleen sprake van discontinuïteit, maar ook wel degelijk van een doorgaande lijn. EN ACTUALITEIT VAN VERSPLINTERD VERSPLINTERD Een versplinterd landschap belicht deze historische lijn voor alle politieke NEDERLANDSE partijen die in 2017 in de Tweede Kamer zijn gekozen. De oudste daarvan bestaat al bijna honderd jaar (SGP), de jongste partijen (DENK en FvD) zijn POLITIEKE PARTIJEN nagelnieuw. Vrijwel alle bijdragen zijn geschreven door vertegenwoordigers van de wetenschappelijke bureaus van de partijen, waardoor een unieke invalshoek is ontstaan: wetenschappelijke distantie gecombineerd met een beschouwing van ‘binnenuit’. Prof. dr. Friso Wielenga is hoogleraardirecteur van het Zentrum für NiederlandeStudien aan de Westfälische Wilhelms Universität in Münster. LANDSCHAP Prof. -

Aantekenen En Per E-Mail Aan Staat Der Nederlanden Namens Deze

Aantekenen en per e-mail Aan Staat der Nederlanden namens deze verantwoordelijk minister Melanie Schultz van Haegen Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu Postbus 20901, 2500 EX Den Haag Van links naar rechts: - Melanie Schultz van Haegen (VVD), huidig Minister van I&M (Infrastructuur en Milieu); - Margreeth de Boer (PvdA), Minister van VROM 1994-1998 - Hans Alders (PvdA), Minister van VROM 1989-1994 - Ed Nijpels (VVD), Minister van VROM 1986-1989 Sint-Oedenrode, 14 maart 2010 Ons kenmerk: C&P/140311/VZ Betreft: - A.M.L. van Rooij, ‟t Achterom 9, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode; - A.M.L. van Rooij, als acoliet voor de RK Kerk H. Martinus Olland (Sint-Oedenrode); - J.E.M. van Rooij van Nunen, ‟t Achterom 9a, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode; - Camping en Pensionstal „Dommeldal‟ (VOF), gevestigd op ‟t Achterom 9-9a, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode; - Van Rooij Holding B.V., gevestigd op ‟t Achterom 9a, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode; - Ecologisch Kennis Centrum B.V., gevestigd op ‟t Achterom 9a, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode, - Politieke partij De Groenen, namens deze A.M.L. van Rooij als lijsttrekker van De Groenen in Sint-Oedenrode, ‟t Achterom 9, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode, Sommatieverzoek tot het nemen van een besluit: 1. dat uw meest corrupte vordering van € 11.859,81 en meest corrupte aangezegde executieprocedure om alle eigendommen van Ad en Annelies van Rooij met hun agrarische bedrijf camping en Pensionstal „Dommeldal‟ (waarin ook Van Rooij Holding B.V., het Ecologisch Kennis Centrum B.V. en het secretariaat van de politieke partij De Groenen, afdeling Sint-Oedenrode zijn gevestigd) te verkopen vóór uiterlijk 21 maart 2011 is ingetrokken; 2. -

Boekbesprekingen Crisis in Het De Poppetjes En De Achtergronden

Boekbesprekingen Crisis in het De poppetjes en de achtergronden Marcel Metze, De stranding. Het van hoogtepunt naar catastrofe (;Nijmegen ) , p., niet meer leverbaar. Pieter Gerrit Kroeger en Jaap Stam, De rogge staat er dun bij. Macht en verval van het - (Balans; Amsterdam ) , p., prijs: ƒ ,. Kees Versteegh, De honden blaffen. Waarom het geen oppositie kan voeren (Bert Bakker; Amsterdam ) , p., prijs: ƒ ,. Een politieke partij aan de geschiedenis waarvan binnen enkele jaren zes dikke boeken wordt gewijd, is een zeldzaamheid. Alleen het is er tot nu toe in geslaagd zoveel belangstelling van historici en journalisten te wekken. In verschenen zo goed als gelijktijdig twee boe- ken over de wording van het , min of meer institutionele geschiedenissen die in werden aangevuld met een studie over de ideologische achtergronden van de groei naar een- heid van de drie grote confessionele partijen in Nederland. Wellicht was dit alles symptoom van – toen nog – de onvermijdelijkheid van de partij in het centrum van de macht. Het was de tijd waarin -kamerlid Joost van Iersel de positie van de christen-democratische con- centratie nog kort en krachtig kon samenvatten in de woorden:‘We run this country.’En daar was weinig tegen in te brengen, even weinig trouwens als tegen de enigszins omineuze titel van Rutger Zwarts studie ‘Gods wil in Nederland’. Inmiddels is echter ook Gods wil in Nederland niet langer wet. Ontkerkelijking en ontzui- ling hebben definitief toegeslagen. En, wat tien jaar geleden niemand had verwacht, zelfs het is aan een ernstige crisis onderhevig nadat het tijdens de Tweede-Kamerverkiezingen van van naar zetels was geduikeld, waarvan er inmiddels nog maar over zijn. -

Conflicts in the Polder

Conflicts in the polder How ministers and top civil servants collide Alexander Kneepkens Universiteit Leiden Conflicts in the polder Alexander Kneepkens 11-06-2012 Conflicts in the polder How ministers and top civil servants collide First supervisor: Alexander Kneepkens Dr. K. Vossen Master thesis Second supervisor: Final version Prof. Dr. R.A. Koole 11-06-2012 S1160605 Total page count: 110 Net page count: 52 3 Conflicts in the polder Alexander Kneepkens 11-06-2012 Table of Contents List of abbreviations ...........................................................................................................................6 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 1: The base .......................................................................................................................... 11 1.1. Introduction............................................................................................................................ 11 1.2. Conceptualization ................................................................................................................... 12 1.3. The development of the bureaucratic system ........................................................................... 18 1.4. The alternatives to the Dutch bureaucratic system ................................................................... 23 1.5. Subconclusion ....................................................................................................................... -

B BOOM105 Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2015

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2015 De Eerste Kamer De Eerste Kamer Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2015 Redactie: Anne Bos Jan Willem Brouwer Hans Goslinga Jan Ramakers Hilde Reiding Jouke Turpijn Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis Nijmegen Boom – Amsterdam Foto omslag: [invullen] Vormgeving: Boekhorst Design, Culemborg © 2015 Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektro- nisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder vooraf- gaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher. isbn 9789089536594 nur 680 www.uitgeverijboom.nl INHOUD Ten geleide 7 ARTIKELEN Hans Goslinga, Eerste Kamer 1815-2015. Een onverlangd cadeau 11 Bert van den Braak, Hoe moeilijk soms ook, uiteindelijk gaat het in 20 de politiek om resultaten. Het laatste woord aan de senaat? Anne Bos, Gevallen in de Eerste Kamer. Hoe de terughoudende senaat 31 vier bewindslieden naar huis stuurde, 1918-2015 Jouke Turpijn, Van een deftige edelman tot een duidelijke tante. 42 De voorzitters van de Eerste Kamer (1815-2015) Carla van Baalen, De Eerste Kamer vergadert. Een impressie van regels, 52 conventies, rituelen en symbolen Douwe Jan Elzinga, Moet er een ander tweekamerstelsel komen? 64 De weeffout uit 1983 breekt het stelsel nu structureel op Inger Stokkink en Kees van Kersbergen, Waarom en hoe de Deense senaat 72 werd afgeschaft SPRAAKMAKEND DEBAT Jan Ramakers en Hilde Reiding, ‘Een nacht van Wiegel, maar dan met drie 85 daders.’ De ‘Kerstcrisis’ in de Eerste Kamer rond de Wet marktordening gezondheidszorg BRONDOCUMENT Anne Bos, De herverkiezing van Eerste Kamervoorzitter Ankie 97 Broekers-Knol UIT DE NOTULEN VAN DE MINISTERRAAD Jan Willem Brouwer, ‘Voor de mannen moet dan het ergste worden 98 gevreesd’. -

OSO. Tijdschrift Voor Surinaamse Taalkunde, Letterkunde En Geschiedenis

OSO. Tijdschrift voor Surinaamse taalkunde, letterkunde en geschiedenis. Jaargang 20 bron OSO. Tijdschrift voor Surinaamse taalkunde, letterkunde en geschiedenis. Jaargang 20. Instituut ter bevordering van de Surinamistiek, [Nijmegen] 2001. Zie voor verantwoording: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_oso001200101_01/colofon.php Let op: werken die korter dan 140 jaar geleden verschenen zijn, kunnen auteursrechtelijk beschermd zijn. [Nummer 1] Afbeeldingen omslag De foto op de voorzijde van de omslag is gemaakt door Vincent Mentzel, tijdens een persconferentie in Paramaribo in 1975. We zien van links naar rechts: Arron, Den Uyl, De Gaaij Fortman en Pronk. De afbeelding op de achterzijde is een maluana. Dit is een ronde houten schijf van bijna een meter middellijn, die door de Wayana-Indianen wordt gebruikt om in ronde huizen de nok van binnen af te sluiten. Op deze maluana, waarvan het origineel in het Academiegebouw te Leiden te zien is, zijn aan weerszijden van het middelpunt figuren afgebeeld die een zogenaamde kuluwayak voorstellen, een dier (geest) met twee koppen en kuifveren. OSO. Tijdschrift voor Surinaamse taalkunde, letterkunde en geschiedenis. Jaargang 20 5 Hans Ramsoedh & Wim Hoogbergen Suriname, 25 jaar Hier en Daar Ooit noemde de Nederlandse premier Joop Den Uyl de onafhankelijkheid van Suriname het grootste wapenfeit van zijn regeerperiode. Het voorbeeld van Suriname illustreert echter hoe pijnlijk dekolonisatie kan zijn. Wat een modeldekolonisatie had moeten worden eindigde in een desillusie. Rond het zilveren Jubileum is veel gedelibereerd over de vragen of Suriname niet te vroeg onafhankelijk werd, of dat het land niet te klein is om volledig onafhankelijk te zijn. De afgelopen 25 jaar was voor het land dan ook geen successtory.