Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Flute Music of Yuko Uebayashi

THE FLUTE MUSIC OF YUKO UEBAYASHI: ANALYTIC STUDY AND DISCUSSION OF SELECTED WORKS by PEI-SAN CHIU Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University July 2016 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Thomas Robertello, Research Director ______________________________________ Don Freund ______________________________________ Kathleen McLean ______________________________________ Linda Strommen June 14, 2016 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to my flute professor Thomas Robertello for his guidance as a research director and as mentor during my study in Indiana University. My appreciation and gratitude also expressed to the committee members: Prof. Kathleen McLean, Prof. Linda Strommen and Dr. Don Freund for their time and suggestions. Special thanks to Ms. Yuko Uebayashi for sharing her music and insight, and being cooperative to make this document happen. Thanks to Prof. Emile Naoumoff and Jean Ferrandis for their coaching and share their role in the creation and performance of this study. Also,I would also like to thank the pianists: Mengyi Yang, Li-Ying Chang and Alber Chien. They have all contributed significantly to this project. Thanks to Alex Krawczyk for his kind and patient assistance for the editorial suggestion. Thanks to Satoshi Takagaki for his translation on the program notes. Finally, I would like to thank my parents Wan-Chuan Chiu and Su-Jen Lin for their constant encouragement and financial support, and also my dearest sister, I-Ping Chiu and my other half, Chen-Wei Wei, for everything. -

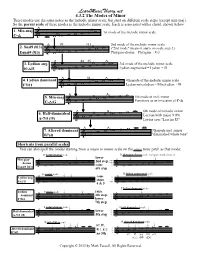

View Printable PDF of 4.2 the Modes of Minor

LearnMusicTheory.net 4.3.2 The Modes of Minor These modes use the same notes as the melodic minor scale, but start on different scale steps (except min-maj). So the parent scale of these modes is the melodic minor scale. Each is associated with a chord, shown below. 1. Min-maj 1st mode of the melodic minor scale C- w wmw ^ & w wmbw w w b9 §13 2nd mode of the melodic minor scale 2. Susb9 (§13) wmw w ("2nd mode" means it starts on scale step 2.) Dsusb9 (§13) & wmbw w w w Phrygian-dorian = Phyrgian + §13 #4 #5 3. Lydian aug. mbw 3rd mode of the melodic minor scale wmw w Lydian augmented = Lydian + #5 Eb ^ #5 & bw w w w #4 4. Lydian dominant 4th mode of the melodic minor scale w wmbw w F7#11 & w w w wm Lydian-mixolydian = Mixolydian + #4 5. Min-maj w w 5th mode of mel. minor wmw wmbw Functions as an inversion of C- C- ^ /G & w w ^ 6th mode of melodic minor 6. Half-diminished w w m w wmbw w Locrian with major 9 (§9) A-7b5 (§9) & w w Levine says "Locrian #2" w 7. Altered dominant wmbw w w w 7th mode mel. minor B7alt & wm w "diminished whole tone" Shortcuts from parallel scales You can also spell the modes starting from a major or minor scale on the same tonic pitch as that mode: D natural minor scale D phrygian-dorian scale (compare marked notes) lower Phrygian- I I 2nd step, I I dorian w bw w w raise _ w nw w w Dsusb9 (§13) & w w w _ & bw w w w 6th step _ w Eb major scale Eb lydian augmented scale Lydian aug. -

Activities Overview 2018,2019 Success of Rohm Music Friends

Activities overview 2019 1 Nishinakamizu-cho, Saiin, Ukyo-ku, Kyoto 615-0044, Japan +81-75-331-7710 +81-75-331-0089 https://micro.rohm.com/en/rmf/ INDEX Objective, Detail of Operation, and Outline of the Foundation ………… 1 Directors, Trustees, Advisors and Members of Selection Committee … 2 Activities 2018 …………………………………………………………………………… 3 2019 …………………………………………………………………………… 9 Success of ROHM Music Friends …………………………………………… 15 (In chronological or alphabetical order.) 2019.9 Objective Directors Our foundation aims to contribute to the dissemination and development of the Japanese musical Chairman Ken Sato Chairman Emeritus ROHM CO., LTD. culture through the implementation of and financial support for music activities, and the provision of Managing Director Akitaka Idei Former Director, Member of the Board ROHM CO., LTD. scholarships for music students. Director Nobuhiro Doi President, Chairman of the Board The Bank of Kyoto, Ltd. Tadanobu Fujiwara President, Detail of Operation Chief Executive Officer ROHM CO., LTD. Yukitoshi Kimura Former Commissioner of the National Tax Agency Board Chairman, Zaikyo 1. Organizing music concerts and providing financial support for music activities Koichi Nishioka Journalist Director, Member of the Board ROHM CO., LTD. 2. Providing scholarships for both Japanese music students studying in Japan or abroad and overseas Seiji Ozawa Conductor music students studying in Japan Yasuhito Tamaki Lawyer Midosuji Legal Profession Corporation 3. Collecting, investigating and analyzing material related to music Mazumi Tanamura Guest Professor Tokyo College of Music Specially Appointed Principal Violist Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra 4. Supporting overseas music research Shunichi Uchida Former Commissioner of the Consumer Affairs Agency President Kyoto International Conference Center Yasunori Yamauchi President and Editor in Chief The Kyoto Shimbun Newspaper Co., Ltd. -

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) The Concertizing Clarinet in the Music of the 20th- 21st Centuries Yu Zhao Department of Musical Upbringing and Education Institute of Music, Theatre and Choreography Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia Saint-Petersburg, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The article deals with stating the problem of a clarinet concert of the 20-21 centuries (one should note in research in ontology of the genre of Clarinet Concert in 20-21 this regard S. E. Artemyev‟s full-featured thesis considering centuries. The author identifies genre variants of long forms the Concerto for clarinet and orchestra of the 18th century). for solo clarinet with orchestra or instrumental ensemble and proposes further steps in making such a research, as well. II. A SHORT GUIDE IN THE HISTORY OF THE CLARINET Keywords—instrumental concert; concertizing; concerto; CONCERT GENRE concert genres; genre diversity Studies in the executive mastership are connected with a research of the evolution of the genres of instrumental music. I. INTRODUCTION The initial period of genesis and development of clarinet concert is investigated widely. Contemporary music in its various genres has become in many aspects a subject of scrupulous studies in musicology. It is known that the most early is the composition of Our research deals with professional problematics of the Antonio Paganelli indicated by the author as Concerto per instrumental concert genre, viewed more narrowly, namely, Clareto (1733). Possibly, it was written for chalumeau, the connected with clarinet performance. instrument-predecessor of the clarinet itself. But, before this time clarinet was used as one of the concertizing instruments The purpose of this article is to identify the situation in the genre of Concerto Grosso, particularly by J. -

Heralding a New Enlightenment

Peculiarities of Clarinet Concertos Form-Building in the Second Half of the 20th Century and the Beginning of the 21st Century Marina Chernaya and Yu Zhao* Abstract: The article deals with clarinet concertos composed in the 20th– 21st centuries. Many different works have been created, either in one or few parts; the longest concert that is mentioned has seven parts (by K. Meyer, 2000). Most of the concertos have 3 parts and the fast-slowly-fast kind of structure connected with the Italian overture; sometimes, the scheme has variants. Our question is: How does the concerto genre function during this period? To answer, we had to search many musical compositions. Sometimes the clarinet is accompanied by orchestra, other times it is surrounded by an ensemble of instruments. More than 100 concertos were found and analyzed. Examples of such concertos were written by C. Nielsen, P. Boulez, J. Adams, C. Debussy, M. Arnold, A. Copland, P. Hindemith, I. Stravinsky, S. Vassilenko, and the attention in the article is focused on them. A special complete analysis is made as regards “Domaines” for clarinet and 21 instruments divided in 6 groups, by Pierre Boulez that had a great role for the concert routine, based on the “aleatoric” principle. The conclusions underline the significant development of the clarinet concerto genre in the 20th -21st centuries, the high diversity of the compositions’ structures, the considerable expressiveness and technicality together with the soloist’s part in the expressive concertizing (as a rule). Further studies suggest the analysis of stylistic and structural peculiarities of the found compositions that are apparently to win their popularity with performers and listeners. -

2019 Round Top Music Festival

James Dick, Founder & Artistic Director 2019 Round Top Music Festival ROUND TOP FESTIVAL INSTITUTE Bravo! We salute those who have provided generous gifts of $10,000 or more during the past year. These gifts reflect donations received as of May 19, 2019. ROUND TOP FESTIVAL INSTITUTE 49th SEASON PArtNER THE BURDINE JOHNSON FOUNDATION HERITAGE CIrcLE H-E-B, L .P. FOUNDERS The Brown Foundation Inc. The Clayton Fund The Estate of Norma Mary Webb BENEFACTORS The Mr. and Mrs. Joe W. Bratcher, Jr. Foundation James C. Dick Mark and Lee Ann Elvig Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation Richard R. Royall V Rose P. VanArsdel SUSTAINERS Blue Bell Creameries, L.P. William, Helen and Georgina Hudspeth Nancy Dewell Braus Luther King Capital Management The Faith P. and Charles L. Bybee Foundation Paula and Kenneth Moerbe Malinda Croan Anna and Gene Oeding Mandy Dealey and Michael Kentor The Gilbert and Thyra Plass Arts Foundation Dickson-Allen Foundation Myra Stafford Pryor Charitable Trust June R. Dossat Dr. and Mrs. Rolland C. Reynolds and Yvonne Reynolds Dede Duson Jim Roy and Rex Watson Marilyn T. Gaddis Ph.D. and George C. Carruthers Tod and Paul Schenck Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation Texas Commission on the Arts Alice Taylor Gray Foundation Larry A. Uhlig George F. Henry Betty and Lloyd Van Horn Felicia and Craig Hester Lola Wright Foundation Joan and David Hilgers Industry State Bank • Fayetteville Bank • First National Bank of Bellville • Bank of Brenham • First National Bank of Shiner ® Bravo! Welcome to the 49th Round Top Music Festival ROUND TOP FESTIVAL INSTITUTE The sole endeavor of The James Dick Foundation for the Performing Arts To everything There is a season And a time to every purpose, under heaven A time to be born, a time to die A time to plant, a time to reap A time to laugh, a time to weep This season at Festival Hill has been an especially sad one with the loss of three of our beloved friends and family. -

Ball State Symphony Orchestra) Saturday, December 8 | 7:30 P.M

COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Robert A. Kvam, dean Michael O’Hara, associate dean SCHOOL OF MUSIC Ryan Hourigan, director Rebecca Braun, assistant to the director Linda Pohly, coordinator of graduate programs in music Kevin Gerrity, coordinator of undergraduate programs in music ORCHESTRA STAFF Douglas Droste, director of orchestras Suzanne Rome and Ian Elmore, graduate assistant conductors Taylor Matthews, librarian APPLIED INSTRUMENT FACULTY Anna Vayman, violin Yu-Fang Chen, violin Zoran Jakovcic, viola Peter Opie, cello Joel Braun, double bass Mihoko Watanabe, flute Lisa Kozenko, oboe Elizabeth Crawford, clarinet Keith Sweger, bassoon Stephen Campbell, trumpet Gene Berger, horn Chris Van Hof, trombone Matthew Lyon, tuba and euphonium Braham Dembar, percussion Elizabeth Richter, harp UPCOMING ORCHESTRA CONCERTS BALL STATE The Nutcracker (Dept. of Theatre and Dance with Ball State Symphony Orchestra) Saturday, December 8 | 7:30 p.m. | Emens Auditorium SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Campus Band and Campus Orchestra Wednesday, December 5 | 7:30 p.m. | Sursa Hall BSSO Performance at IMEA Professional Development Conference Douglas Droste, conductor Friday, January 18 | 2:30 p.m. | Grand Wayne Center (Fort Wayne) BSSO Tour and Performance at CODA National Conference Chris Van Hof, trombone February 7–9 | Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts BSSO with Undergraduate Concerto Competition Winners Tuesday, February 26 | 7:30 p.m. | Sursa Hall Ball State Opera Theatre with BSSO: Mozart’s Don Giovanni Friday, March 29 (7:30 p.m.) and Sunday, March 31 (2 p.m.) | Sursa Hall Campus Orchestra Wednesday, April 10 | 7:30 p.m. | Sursa Hall Masterworks Concert featuring Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 Friday, April 12 | 7:30 p.m. -

State-Of-The-Art Report on Multi-Scale Modelling Methods

Nuclear Science NEA/NSC/R(2019)2 June 2020 www.oecd-nea.org State-of-the-Art Report on Multi-Scale Modelling Methods Nuclear Energy Agency NEA/NSC/R(2019)2 Unclassified English text only 11 June 2020 NUCLEAR ENERGY AGENCY NUCLEAR SCIENCE COMMITTEE State-of-the-Art Report on Multi-Scale Modelling Methods Please note that this document is available in PDF format only. JT03462919 OFDE This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. 2 NEA/NSC/R(2019)2 │ ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT The OECD is a unique forum where the governments of 37 democracies work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. -

Proquest Dissertations

A comparison of embellishments in performances of bebop with those in the music of Chopin Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Mitchell, David William, 1960- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 23:23:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/278257 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the miaofillm master. UMI films the text directly fi^om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fi-om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and contLDuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

Linearity, Modulation, and Virtual Agency in Prokofiev's War Symphonies

Copyright by Joel Davis Mott 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Joel Davis Mott Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: A New Symphonism: Linearity, Modulation, and Virtual Agency in Prokofiev's War Symphonies Committee: Robert Hatten, Supervisor Byron Almén Inessa Bazayev Eric Drott Marianne Wheeldon A New Symphonism: Linearity, Modulation, and Virtual Agency in Prokofiev's War Symphonies by Joel Davis Mott Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2018 Dedication for Ashley Acknowledgements This dissertation is a product of the support of faculty, family, and friends. I am indebted to Dr. Robert S. Hatten’s insight into musical meaning and movement along with his unwavering support and careful guidance. Dr. Byron Almén fostered my early interest in musical narrative. Dr. Marianne Wheeldon oversaw my first efforts to analyze Prokofiev’s music in historical and cultural context. Dr. Edward Pearsall assisted in my application of musical forces to the piano sonatas. I worked with Dr. Eric Drott to understand what it meant for Prokofiev to write a Soviet Symphony. Dr. David Neumeyer ensured I applied my work in his Schenkerian analysis course to my work on Prokofiev’s music. I am also grateful to Dr. Daniel Harrison at Yale University, whose work on tonality post-1900 helped formulate my approach to the War Symphonies. I am thankful for the ideas, support, and encouragement of my fellow graduate students during my time at UT Austin, including Garreth Broesche, Eloise Boisjoli, Catrin Watts, Eric Hogrefe, Matthew Bell, Steven Rahn, Bree Geurra, and Scott Schumann. -

How to Incorporate Bebop Into Your Improvisation by Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics

How to Incorporate Bebop into Your Improvisation By Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics • Bebop Characteristics & Style • Scales & Arpeggios • Exercises & Patterns • Articulations & Accents • Listening Bebop Characteristics & Style • Developed in the early to mid 1940’s • Medium to fast tempos • Rapid chord progressions / changes • Instrumental “virtuosity” • Simple to complex harmony - altered chords / substitutions • Dominant syncopation of rhythms • New melodies over existing chord changes - Contrafacts Scales & Arpeggios • Scales and arpeggios are the building blocks for harmony • Use of the half-step interval and rapid arpeggiation are characteristic of bebop playing • Because bebop is often played at a fast tempo with rapidly changing chords, it’s crucial to practice your scales and arpeggios in ALL KEYS! Scales & Arpeggios • Scales you should be familiar with: • Major Scale - Pentatonic: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 • Minor Scales - Pentatonic: 1, b3, 4, 5, b7; Natural Minor, Dorian Minor, Harmonic Minor, Melodic Minor • Dominant Scales - Mixolydian Mode, Bebop Scales, 5th Mode of Harmonic Minor (V7b9), Altered Dominant / Diminished Whole Tone (V7alt, b9#9b13), Dominant Diminished / Diminished starting with a half step (V7b9#9 with #11, 13) • Half-diminished scale - min7b5 (7th mode of major scale) • Diminished Scale - Starting with a whole step (WHWHWHWH) Scales & Arpeggios • Chords and Arpeggios to work in all keys: • Major triad, Maj6/9, Maj7, Maj9, Maj9#11 • Minor triad, m6/9, m7, m9, m11, minMaj7 • Dominant 7ths • Natural extensions - 9th, 13th