POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archi-Ne Ws 2/20 17

www.archi-europe.com archi-news 2/2017 BUILDING AFRICA EDITO If the Far East seems to be the focal point of the contemporary architectural development, the future is probably in Africa. Is this continent already in the line 17 of vision? Many European architects are currently building significant complexes: 2/20 the ARPT by Mario Cucinella, the new hospital in Tangiers by Architecture Studio or the future urban development in Oran by Massimiliano Fuksas, among other projects. But the African architectural approach also reveals real dynamics. This is the idea which seem to express the international exhibitions on African architecture during these last years, on the cultural side and architectural and archi-news archi-news city-panning approach, as well as in relation to the experimental means proposed by numerous sub-Saharan countries after their independence in the sixties, as a way to show their national identity. Not the least of contradictions, this architecture was often imported from foreign countries, sometimes from former colonial powers. The demographic explosion and the galloping city planning have contributed to this situation. The recent exhibition « African Capitals » in La Villette (Paris) proposes a new view on the constantly changing African city, whilst rethinking the evolution of the African city and more largely the modern city. As the contemporary African art is rich and varied – the Paris Louis Vuitton Foundation is presently organizing three remarkable exhibitions – the African architecture can’t be reduced to a single generalized label, because of the originality of the different nations and their socio-historical background. The challenges imply to take account and to control many parameters in relation with the urbanistic pressure and the population. -

Architecture

ARCHITECTURE LE MUSEE SOULAGES, UN ECRIN POUR DES ŒUVRES SINGULIERES Service Educatif Musée Soulages – Service Educatif - Professeurs chargés de mission ARCHITECTURE- Le musée Soulages un écrin pour des œuvres singulières Sommaire 1 Musée Soulages : le projet ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Présentation générale ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Le temps du projet .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Le concours ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 L’architecture du musée Soulages .................................................................................................................................. 4 L’agence RCR arquitectes ................................................................................................................................................ 5 2 La démarche RCR, le point de vue des architectes ........................................................................................................... 6 Les sources d’inspiration ................................................................................................................................................ -

88/2005, Uradne Objave

Uradni list Republike Slovenije Uradne objave Internet: http://www.uradni-list.si e-pošta: [email protected] Št. Ljubljana, torek ISSN 1318-9182 Leto XV 88 4. 10. 2005 Obrazložitev: Ker proti sklepu o začetku Sedež: Tržaška 11 a, 6230 POSTOJNA izbrisa ni bil vložen ugovor, je sodišče na Ustanovitelji: HALJITI SADIJE gospodi- Sodni register podlagi prvega odstavka 32. člena Zakona nja, Dobri dol b.š., GOSTIVAR, MAKEDO- o finančnem poslovanju podjetij (Ur. list RS, NIJA, odg. s svojim premož., vstop: 26. 3. št. 54/99 in 110/99) izdalo sklep o izbrisu 2001; HALITI MUSTAFA trgovec, Tržaška Sklepi o izbrisu po 33. členu gospodarske družbe iz sodnega registra. 11, 6230 POSTOJNA, osnovni vložek: 1.000 ZFPPod Pravni pouk: Zoper sklep je dopustna pri- SIT, ne odgovarja, vstop: 26. 3. 2001. tožba v roku 30 dni, ki začne teči: – za Obrazložitev: Ker proti sklepu o začetku gospodarsko družbo od vročitve sklepa o izbrisa ni bil vložen ugovor, je sodišče na izbrisu – za družbenika oziroma delničarja podlagi prvega odstavka 32. člena Zakona CELJE gospodarske družbe ali upnika gospodar- o finančnem poslovanju podjetij (Ur. list RS, ske družbe od objave sklepa o izbrisu v št. 54/99 in 110/99) odločilo, da se v izre- Sr-26308/05 Uradnem listu RS. Pritožba se vloži v dveh ku navedena gospodarska družba izbriše iz OKROŽNO SODIŠČE V CELJU je s izvodih pri tem sodišču. O pritožbi bo od- sodnega registra. Pravni pouk: Zoper sklep sklepom Srg št. 2005/01910 z dne 27. 9. ločalo višje sodišče. je dopustna pritožba v roku 30 dni, ki začne 2005 pod št. -

LAUREADOS PRITZKER PRIZE PRITZKER 2018 Balkrishna Doshi Pune,Índia,1927

LAUREADOS PRITZKER PRIZE PRITZKER 2018 Balkrishna Doshi Pune,Índia,1927 • Estudante e colaborador de Le Corbusier e Louis Kahn • Em atividade profissional há mais de 70 anos, • Princípios • Arquitetura poética • Influências das culturas orientais • Amplo espectro de programas arquitetônicos desde a década de 1950 • Doshi é o primeiro arquiteto indiano a receber a maior honra da arquitetura. Iniciou seus estudos de arquitetura no ano da independência de seu país, 1947 • Depois de um período em Londres, mudou-se para a França para trabalhar com Le Corbusier, voltando para a Índia para supervisionar o trabalho de Le Corbusier em Chandigarh e Ahmedabad (Edifício da Associação de Proprietários de Moinhos (1954) e a Casa Shodhan (1956). • Também trabalhou com Louis Kahn no Instituto Indiano de Gestão em Ahmedabad, que teve início em 1962 Hussein Doshi Gufa em Ahmedabad Galeria de arte que lembra uma caverna exibe o trabalho do artista Maqbool Fida Husain. Muito parecidas com o estúdio Sangath, as estruturas em forma de cúpulas são revestidas de mosaicos. As obras de arte são afixadas diretamente nas paredes internas e as esculturas de metal repousam contra as colunas de forma irregular Juri • Júri do Prêmio Pritzker de 2018 –Glenn Murcutt (presidente), Stephen Breyer, André Aranha Corrêa do Lago, Yung Ho Chang, Kristin Feireiss, Lord Peter Palumbo, Richard Rogers, Benedetta Tagliabue, Ratan N. Tata, Kazuyo Sejima, Wang Shu e Martha Thorne – justificou deste modo a sua atribuição a Balkrishna Doshi: “O arquitetco indiano Balkrishna Doshi tem continuamente apresentado na sua obra os objectivos do Prêmio Pritzker de Arquitetura no mais alto grau. Tem praticado a arte da arquitectura, mostrando contribuições substanciais para a humanidade, há mais de 60 anos. -

From Slovenian Farms Learn About Slovenian Cuisine with Dishes Made by Slovenian Housewives

TOURISM ON FARMS IN SLOVENIA MY WAY OF COUNTRYSIDE HOLIDAYS. #ifeelsLOVEnia #myway www.slovenia.info www.farmtourism.si Welcome to our home Imagine the embrace of green 2.095.861 surroundings, the smell of freshly cut PEOPLE LIVE grass, genuine Slovenian dialects, IN SLOVENIA (1 JANUARY 2020) traditional architecture and old farming customs and you’ll start to get some idea of the appeal of our countryside. Farm 900 TOURIST tourism, usually family-owned, open their FARMS doors and serve their guests the best 325 excursion farms, 129 wineries, produce from their gardens, fields, cellars, 31 “Eights” (Osmice), smokehouses, pantries and kitchens. 8 camping sites, and 391 tourist farms with Housewives upgrade their grandmothers’ accommodation. recipes with the elements of modern cuisine, while farm owners show off their wine cellars or accompany their guests to the sauna or a swimming pool, and their MORE THAN children show their peers from the city 200.000 how to spend a day without a tablet or a BEE FAMILIES smartphone. Slovenia is the home of the indigenous Carniolan honeybee. Farm tourism owners are sincerely looking Based on Slovenia’s initiative, forward to your visit. They will help you 20 May has become World Bee Day. slow down your everyday rhythm and make sure that you experience the authenticity of the Slovenian countryside. You are welcome in all seasons. MORE THAN 400 DISTINCTIVE LOCAL AND REGIONAL FOODSTUFFS, DISHES AND DRINKS Matija Vimpolšek Chairman of the Association MORE THAN of Tourist Farms of Slovenia 30.000 WINE PRODUCERS cultivate grapevines on almost 16,000 hectares of vineyards. -

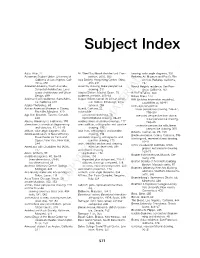

Subject Index

Subject Index Aalto, Alvar, 22 Art Shed Southbank Architectural Com- bearing, solar angle diagrams, 334 Ackerman Student Union, University of petition, 2006, 383 Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film California at Los Angeles, Cali- Asia Society, Hong Kong Center, China, Archive, Berkeley, California, fornia, 250 410, 411 197 Adelaide University, South Australia, assembly drawing, linear perspective Bernal Heights residence, San Fran- School of Architecture, Land- drawing, 311 cisco, California, 262 scape Architecture and Urban Atocha Station, Madrid, Spain, 75 B FIVE STUDIO, 550 Design, 499 audience, portfolio, 463–64 Bilbao Effect, 120 Adelman/Liano residence, Santa Moni- August Wilson Center for African Ameri- BIM (building information modeling), ca, California, 207 can Culture, Pittsburgh, Penn- capabilities of, 93–94 Adobe Photoshop, 63 sylvania, 284 bird’s eye perspective African American Museum of Slavery, Aulenti, Gaetana, 22 linear perspective drawing, 246–47, Rockville, Maryland, 429 automobile 298–301 Aga Han Museum, Toronto, Canada, conceptual sketching, 73 one-point perspective from above, 242 representational drawing, 26–29 linear perspective drawing, Alaska, University of, Fairbanks, 198 auxiliary views, multiview-drawings, 177 248–49 alternatives, conceptual diagramming axes addition, orthographic and paraline underside perspective with, linear and sketches, 40, 44–45 drawing, 195 perspective drawing, 303 altitude, solar angle diagrams, 334 axial lines, orthographic and paraline Birkerts, Gunnar, 42, 69, 150 American Museum -

25. April 1974 (Št. 1292)

Št. 17 (1292) Leto XXV NOVO MESTO, četrtek, 25. aprila 1974 Izjemno dobre volitve Ob t. maju Prvi maj ima izredno po V Posavju ni bilo volišča z negativnim izidom membno vlogo v zgodovini borbe delavskega razreda in 27.6 odst. žena, mladih je 18,4 odst. Medobčinski svet ZK za Posavje' naprednega človeštva sploh. BREŽICE - Nocoj ob 20. uri je 17. aprila na seji v Sevnici Večina izvoljenih delegatov je starih bo v prosvetnem domu koncert 27 do 35 let. Neposrednih proizva Njegov pomen ni samo v nje zamejskih in domačih pevskih nadvse ugodno ocenil volitve jalcev je kar 89 odst. Med njimi je govi zunanji podobi; to je od zborov v počastitev dneva mla delegatov v nove občinske po posameznih zborih od 15,66 do vseh proslav v drugi polovici 26.7 odst. članov ZK. Med nadalj dosti in 1. maja. skupščine. Kot je dejal namest 19. stoletja najbolj razgiban NOVO MESTO - Danes bo nik sekretarja medobčinskega njimi nalogami bo zato poleg uspo skupščina solidarnostnega stano sabljanja delegatov pomembno tudi nastop delavskih sil, pre vanjskega sklada ponovila sejo. sveta ZK in sekretar komiteja politično delo med delegati, da bi izkus vsakega posameznika, Prejšnji teden se sklic ni posre občinske konference ZK Sevni jih kar največ vključili tudi v član neizprosno opozorilo raz čil ca Viktor Auer, gre za najugod- stvo ZK. Člani sveta so ugodno oce rednemu sovražniku. METLIKA - Na današnji, nješe volilne rezultate po letu nili tudi odmeve na.minuli VII. kon zadnji seji „odbomiške" občin gres slovenskih komunistov tako ske skupščine bodo odborniki 1954. med članstvom in občani. -

18. December 1980

Jeklena morala, podružUjena Dvanajsta živi naprej Zoor XII. SNOUB — Priznanja jubilantom — Novi načrti _ obramba V hotelu Metropol v Novem so v novoustanovljenem območnem mestu so se 13. decembra srečali Ob dnevu JLA odboru, ki ga vodi Anton Kramarič, nekdanji borci XII. SNOUB iz predstavniki vseh dolenjskih obmo ^Obramba Jugoslavije in zmaga novomeškega, črnomaljskega, krško čij. sovražnikom v vseljudski -brežiScega in kočevsko -ribniškega Na slovesnosti, za katero so ^m bni vojni bi bili v prvi vrsti okrožja z namenom, da ustanovijo kulturni program pripravili pionirji sni od čvrstosti morale in od območni odbor in da podelijo osnovne šole iz Bršljina, ki nadaljuje 'tične zavesti pripadnikov oboro- priznanja borcem--jubilantom. tradicije legendarne ..Dvanajste”, so ^ n|n sil in vseh članov družbe, Oktobra letos je minilo 37 let, podelili priznanja osemdesetim bor ^legijska prednost v bojni morali odkar se je brigada v Mokronogu cem, ki so že dopolnili 60. leto. «lo močno in učinkovito orožje, prvič postrojila. Njena borbena pot, Naslednja leta pa bodo priznanja Pfav je jasno, da se jugoslovanska na kateri so ostali mnogi borci, je prejeli le tisti, ki bodo v letu ‘ ba tru d i in tu d i uspeva z drugi- del naše revolucije in del naše dopolnili okrogli življenjski jubilej. ,'^ d a m i držati korak tudi s zmage. Borci ,,Dvanajste” so doma Ob zaključku proslave so borci r , a tehnične opremljenosti obo- po vsej Sloveniji in se združujejo v prvič prisluhnili svoji himni, ki so jo ^ enih sil. Sadovi teh naporov so 12 območnih odborov, ki imajo prav zanje pripravili ljubljanski sedeže v Ljubljani, Mariboru, Celju, glasbeni umetniki Nobei nega sovražnika ne gre pod- Litiji, Radovljici, Kopru, Gro J. -

The Designed Israeli Interior, 19601977

The ‘‘Designed’’ Israeli Interior, 1960–1977: Shaping Identity Daniella Ohad Smith, Ph.D., School of Visual Arts ABSTRACT The concept of a ‘‘home’’ had played an important role during the early decades of Israel’s establishment as a home for all the Jewish people. This study examines the ‘‘designed’’ home and its material culture during the 1960s and 1970s, focusing on aesthetic choices, approaches, and practices, which came to highlight the home’s role as a theater for staging, creating, and mirroring identities, or a laboratory for national boundaries. It seeks to identify the conceptualization of the domestic space during fundamental decades in the history of Israel. Introduction and conventions in interior design developed and shifted to other countries been recognized and The concept of a ‘‘home’’ played an important role examined.4 The process of importing and shifting during the early decades of Israel’s establishment as a 1 ideas is particularly relevant to a country such as homeland for all Jewish people. Israel, which has attracted immigrants from many parts of the world during the discussed period. This study aims to provide a detailed scholarly Yet, while the creation of modernist architecture in appraisal of the conceptualization of domestic Israel has received substantial scholarly attention, the interiors between 1960 and 1977, two of the most interior spaces within these white architectural shells formative decades of Israel’s history. It examines the have been excluded from an academic discussion until ‘‘designed’’ home, its comparative analysis to the recently.5 ‘‘ordinary’’ home, and its material culture. It focuses on aesthetic choices, methodologies, and practices This research comes to fill a gap in the literature that highlighted the role of the home as a theater for on residential interiors. -

Hišna Imena Kot Del Kulturne Dediščine

ARTICLE IN PRESS TRADITIONAL HOUSE NAMES AS PART OF CULTURAL HERITAGE Klemen Klinar, Matjaž Geršič #Domačija Pәr Smôlijo v Srednjem Vrhu nad Gozd - Martuljkom The Pәr Smôlijo farm in Srednji Vrh above Gozd Martuljek KLEMEN KLINAR ARTICLE IN PRESS Traditional house names as part of cultural heritage DOI: 10.3986/AGS54409 UDC: 811.163.6'373.232.3(497.452) COBISS: 1.02 ABSTRACT: Traditional house names are a part of intangible cultural heritage. In the past, they were an important factor in identifying houses, people, and other structures, but modern social processes are decreasing their use. House names preserve the local dialect with its special features, and their motivational interpretation reflects the historical, geographical, biological, and social conditions in the countryside. This article comprehensively examines house names and presents the methods and results of collecting house names as part of various projects in Upper Carniola. KEYWORDS: traditional house names, geographical names, cultural heritage, Upper Carniola, onomastics The article was submitted for publication on November 15, 2012. ADDRESSES: Klemen Klinar Northwest Upper Carniola Development Agency Spodnji Plavž 24e, SI – 4270 Jesenice, Slovenia Email: [email protected] Matjaž Geršič Anton Melik Geographical Institute Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts Gosposka ulica 13, SI – 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia Email: [email protected] ARTICLE IN PRESS 1 Introduction “Preserved traditional house names help determine historical and family conditions, social stratification and interpersonal contacts, and administrative and political structure. Immigration and emigration are very important aspects of social culture and they have left a strong trace in the house names in the Žiri area” (Zorko, cited in Stanonik 2005, frontispiece). -

Via Urbium 06

Dravska 01 Pekrska gorca 02 Bresterniško jezero 03 Pustolovska 04 Forma Viva 05 TIC Maribor 5 km nezahtevna/undemanding/anspruchslos TIC Maribor 24 km srednje zahtevna/intermediate/mittelschwer TIC Maribor 14 km srednje zahtevna/intermediate/mittelschwer TIC Maribor 17 km nezahtevna/undemanding/anspruchslos TIC Maribor 16 km nezahtevna/undemanding/anspruchslos • Potek poti / Route / Verlauf des Weges: • Potek poti / Route / Verlauf des Weges: • Potek poti / Route / Verlauf des Weges: • Potek poti / Route / Verlauf des Weges: • Opis / Description / Beschreibung: Forma viva predstavlja v Mariboru pomemben TIC Partizanska cesta – Trg Svobode – Grajski trg – Slovenska ul. – Gosposka ul. – Glavni trg – Koroška cesta TIC Partizanska cesta – Trg Svobode – Grajski trg – Slovenska ul. – Gosposka ul. – Glavni trg – Koroška TIC Partizanska cesta – Trg svobode – Trg generala Maistra – Ul. heroja Staneta – Maistrova ul. – Prešernova TIC Partizanska cesta – Titova cesta (Titov most) – Pobreška cesta – Čufarjeva cesta – Ul. Veljka Vlahoviča – umetniški poseg v urbano strukturo mesta, ki ponuja izjemno atraktiven vpogled v skrivnosti in različne značaje mesta Vsak udeleženec vozi po predlaganih poteh na lastno odgovornost in - Splavarski prehod – Ob bregu (Lent) – Studenška brv – obrežje Drave (bank of the river Drava, das Ufer der cesta – Splavarski prehod – Ob bregu (Lent) – Studenška brv – obrežje Drave (bank of the river Drava, das ul. – Tomšičeva ul. – Ribniška ul. – Za tremi ribniki (Ribniško selo) – Vinarje – Vrbanska cesta – Kamnica – Cesta XIV. divizije – Kosovelova ul. (Stražun) – Štrekljeva ul. – Janševa ul. – Ptujska cesta – Cesta Proletarskih Maribor – tako v mestnem jedru kot tudi v posameznih mestnih četrtih. Z željo opozoriti na to dragoceno kulturno Drau) – Dvoetažni most – Oreško nabrežje – Mlinska ul. – Partizanska cesta – TIC Partizanska cesta Ufer der Drau) – Obrežna ul. -

City Portraits AARHUS 365

364 City portraits AARHUS 365 Kathrine Hansen Kihm and Kirstine Lilleøre Christensen History and general information One of the oldest nations in Europe, the Kingdom of Denmark is today a constitutional monarchy as well as a modern Nordic welfare state. Aarhus is located in Central Denmark on the eastern side of the Jutland peninsula. Jutland is the only part of Denmark that is connected to the mainland of Europe as 41% of the country consists of 443 named islands. The capital Copenhagen is on the island Zealand (Sjælland in Danish), which is 157 km south-east of Aarhus measured in a straight line and 303 km when driving across the island2 Funen (Fyn in Danish). Aarhus has 242,914 inhabitants2 in the urban area (of 91 km ) and 306,650 in the municipal area (of 467 km ). Aarhus is the second largest city in Denmark not only measured in size, but also in the extent of trade, education, industry and cultural activities. The main employers of Aarhus are the Aarhus Municipality and the Aarhus University Hospital. th Aarhus originated in the 8 century from a Viking settlement, which was built around Aarhus River and still marks the centre of town and laid the foundation for the major industrial port that Aarhus has today. Many old buildings in the city have been preserved, for example, the Aarhus Custom House (Toldkammeret), the Aarhus Theatre (Aarhus Teater), Marselisborg Palace (Marselisborg Slot) and the Aarhus Cathedral, which represent historic landmarks across the city. Aarhus is a pulsating city offering a broad range of educational institutions and a vibrant and active student life.