1 the Turin Shroud and St. Raphael's Church David A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebuttal to Joe Nickell

Notes Lorenzi, Rossella- 2005. Turin shroud older than INQUIRER 28:4 (July/August), 69; with thought. News in Science (hnp://www.abc. 1. Ian Wilson (1998, 187) reported that the response by Joe Nickell. net.au/science/news/storics/s 1289491 .htm). 2005. Studies on die radiocarbon sample trimmings "are no longer extant." )anuary 26. from the Shroud of Turin. Thermochimica 2. Red lake colors like madder were specifically McCrone, Walter. 1996. Judgment Day for the -4CM 425: 189-194. used by medieval artists to overpaim vermilion in Turin Shroud. Chicago: Microscope Publi- Sox, H. David. 1981. Quoted in David F. Brown, depicting "blood" (Nickell 1998, 130). cations. Interview with H. David Sox, New Realities 3. Rogers (2004) does acknowledge that Nickell, Joe. 1998. Inquest on the Shroud of Turin: 4:1 (1981), 31. claims the blood is type AB "are nonsense." Latest Scientific Findings. Amherst, N.Y.: Turin shroud "older than thought." 2005. BBC Prometheus Books. News, January 27 (accessed at hnp://news. References . 2004. The Mystery Chronicles. Lexington, bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/—/2/hi/scicnce/naturc/421 Damon, P.E., et al. 1989. Radiocarbon dating of Ky.: The University Press of Kentucky. 0369.stm). the Shroud of Turin. Nature 337 (February): Rogers, Raymond N. 2004. Shroud not hoax, not Wilson, Ian. 1998. The Blood and the Shroud New 611-615. miracle. Letter to the editor, SKEPTICAL York: The Free Press. Rebuttal to Joe Nickell RAYMOND N. ROGERS oe Nickell has attacked my scien- results from Mark Anderson, his own an expert on chemical kinetics. I have a tific competence and honesty in his MOLE expert? medal for Exceptional Civilian Service "Claims of Invalid 'Shroud' Radio- Incidentally, I knew Walter since the from the U.S. -

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

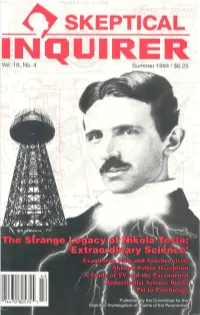

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses

TThhee SShhrroouudd ooff TTuurriinn A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses If the truth were a mere mathematical formula, in some sense it would impose itself by its own power. But if Truth is Love, it calls for faith, for the ‘yes’ of our hearts. Pope Benedict XVI Version 4.0 Copyright 2017, Turin Shroud Center of Colorado Preface The purpose of the Critical Summary is to provide a synthesis of the Turin Shroud Center of Colorado (TSC) thinking about the Shroud of Turin and to make that synthesis available to the serious inquirer. Our evaluation of scientific, medical forensic and historical hypotheses presented here is based on TSC’s tens of thousands of hours of internal research, the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) data, and other published research. The Critical Summary synthesis is not itself intended to present new research findings. With the exception of our comments all information presented has been published elsewhere, and we have endeavored to provide references for all included data. We wish to gratefully acknowledge the contributions of several persons and organizations. First, we would like to acknowledge Dan Spicer, PhD in Physics, and Dave Fornof for their contributions in the construction of Version 1.0 of the Critical Summary. We are grateful to Mary Ann Siefker and Mary Snapp for proofreading efforts. The efforts of Shroud historian Jack Markwardt in reviewing and providing valuable comments for the Version 4.0 History Section are deeply appreciated. We also are very grateful to Barrie Schwortz (Shroud.com) and the STERA organization for their permission to include photographs from their database of STURP photographs. -

Gregory Rich Aldous Huxley Characterized Time Must Have A

“Life After Death in Huxley’s Time Must Have a Stop ” Gregory Rich Aldous Huxley characterized Time Must Have a Stop as “a piece of the Comedie Humaine that modulates into a version of the Divina Commedia ” (qtd. in Woodcock 229). To be sure, some of the dialogue includes good-natured banter, frivolous wit, and self-deprecating humor. But some of the human comedy goes further and satirizes human imperfections. For instance, the novel portrays a “jaded pasha” ( Time 67), most interested in his own pleasure, a pretentious scholarly man who talks too much ( Time 79), and a beautiful young woman who believes that the essence of life is “pure shamelessness” and lives accordingly ( Time 128). Some of the novel’s comedy is darkly pessimistic. For example, there are references to the cosmic joke of good intentions leading to disaster ( Time 194). And there are sarcastic indictments of religion, science, politics, and education ( Time 163-64). In the middle of the novel, when one of the main characters dies, the scene shifts to an after-life realm, to something like a divine-comedy realm. Both Dante’s Divine Comedy and Huxley’s Time Must Have a Stop depict an after-death realm but provide different descriptions of it. In Dante’s book, a living man takes a guided tour of hell and sees the punishments that 2 have been divinely assigned for various serious sins. In contrast, Huxley’s book depicts the experiences of a man after he has died. He seems to be in some kind of dream world, where there is no regular succession of time or fixed sense of place ( Time 222). -

By Pastor Ian Wilson

By Pastor Ian Wilson Several times over the past 50 or so years, I have been involved in the exciting adventures of pioneering a church or reviving those that had decayed to the point of closure. I had only been a Christian for a matter of a month or so when I realized that my ‘mother’ church of England could not sustain or nourish my new-found faith in Christ. I was living in an industrial and mining town in the North of England and the year was 1962. In February of that year, I had had a Damascus Road Experience with Jesus Christ while attending Bede College in Durham City. This was no gentle awakening. It was a blinding, life changing God encounter which left me with only one desire and that was to serve Christ wherever He led me. There was a man living in my town called Bill Healey. He was known as the Singing Garbage Man and it was Bill who introduced me to his church. It was a Pentecostal Assembly that had been established after revivals led by Stephen Jefferies and Smith Wigglesworth. They met in a rickety building that had once belonged to a Baptist church. The top floor had been sealed off and was the home for a flock of pigeons, but on the lower floor were organs, pews and a congregation of 25 to 30 saints. It was here that, week by week on Sundays, I enjoyed the Presence of God and the fellowship of these large-hearted saints who were filled with the Holy Ghost and the love of God. -

Science and the Shroud of Turin

Science and the Shroud of Turin © May 2015 Robert J. Spitzer, S.J., Ph. D. Magis Center of Reason and Faith Introduction The Shroud of Turin is a burial shroud (a linen cloth woven in a 3-over 1 herringbone pattern) measuring 14 ft. 3 inches in length by 3 ft. 7 inches in width. It apparently covered a man who suffered the wounds of crucifixion in a way very similar to Jesus of Nazareth. (Notice the position of the blood stains—the bold brown color—in relation to the image of the body—the fainter sepia hue—in Figure 1 below). Figure 1 The cloth has a certifiable history from 1349 when it surfaced in Lirey, France in the hands of a French nobleman – Geoffrey de Charny.1 It also has a somewhat sketchy traceable history from Jerusalem to Lirey, France – through Edessa, Turkey and Constantinople.2 This 1 This history is recounted in Appendix I (Section I) of a forthcoming book God So Loved the World: Clues to our Transcendent Destiny from the Revelation of Jesus (Ignatius Press -- coming 2016). The history is well captured in Wilson, Ian. 1978. The Shroud of Turin (New York: Doubleday). 2 This history is recounted in Appendix I of my forthcoming book God So Loved the World: Clues to our Transcendent Destiny from the Revelation of Jesus (Ignatius Press – coming 2016). There are six important sources of this history: De Gail, Paul. 1983. “Paul Vignon” in Shroud Spectrum International 1983 (6) (https://www.shroud.com/pdfs/ssi06part7.pdf). John Long 2007 (A) “The Shroud of Turin's Earlier History: Part One: To Edessa” in Bible and Spade Spring 2007 (http://www.biblearchaeology.org/post/2013/03/14/The-Shroud-of-Turins-Earlier-History-Part-One-To- Edessa.aspx). -

Copyrighted Material

25555 Text 10/7/04 8:56 AM Page 13 1 the enigma of the holy shroud The Shroud of Turin is the holiest object in Christendom. To those who believe, it is proof not only of Jesus the man, but it is also evidence of the Resurrection, the central dogma for hundreds of millions of the faithful. Regarded as the winding sheet, the burial cloth of Jesus, it is revered by many, and on the rare instances when it is displayed, the lines to view the Shroud go on for hours. The Shroud measures fourteen feet three inches long and three feet seven inches wide. It depicts the full image of a six-foot-tall man with the visible consequences of a savage beating and cruel death on the cross, in other words, crucifixion. Belief in the authenticity of the Shroud is not uni- versal. To critics it is a medieval production, created either by paint or by a more remarkable process not to be duplicated until photography was in- vented in the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, a fake. Despite the debate about the Shroud’s authenticity, it has been de- scribed as “one of the most perplexing enigmas of modern time.” This enigma has been the subject of study by an army of chemists, physicists, pathologists, biblical scholars, and art historians. Experts on textiles, pho- tography, medicine, and forensic science have all weighed in with an opin- ion.1 Had theCOPYRIGHTED image on the burial cloth MATERIALbeen that of Charlemagne or Napoleon, the debate might have proceeded along scientific lines. -

BSTS Newsletter No. 78

BRITISH SOCIETY FOR THE TURIN SHROUD NEWSLETTER 78 EDITORIAL !It has been allotted to me to follow to the Editor’s chair two truly towering figures in Shroud Studies. Their knowledge of the Shroud itself, their association with others in the field and their own primary research has amounted to a number of significant advances. Ian Wilson’s works are almost invariably the first line of approach for anybody beginning an investigation into the Shroud, and his research into the Mandylion of Edessa has stimulated a mass of concomitant investigation, both for and against his hypothesis; and Mark Guscin’s work on the Sudarium of Oviedo has opened up a whole new context for exploration, geographical, historical and cultural. !Besides these, my qualifications as an expert on the Shroud are so meagre as to be insignificant. A bit of kitchen science here, and a determination to read all the primary sources there, have given me information but not experience, a lot of knowledge, but not the intimate involvement of my predecessors. !But perhaps that’s the point, so let me introduce myself. I have been Head of Science at a Catholic School for nearly forty years, and a member of the BSTS for most of that time. For me the ‘Religion versus Science’ debate has been far from academic, and I have often found myself having to defend (or explain) their essential synthesis in the face of extremists from both sides. My first introduction to the Shroud was by reading Barbet and Vignon, and my first investigations stimulated by an almost forgotten 1982 BBC documentary, “Shroud of Jesus: Fact or Fake.” !Unlike my predecessors, whom I think are more or less committed to a pro-authenticity point of view, I myself currently incline more towards an accidental 14th century origin for the cloth now preserved in Turin. -

“The Centrality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and Its Implications For

“The Centrality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and its Implications for Missions in a Multicultural Society” INTRODUCTION: Christianity stands or falls with the bodily resurrection of Jesus. The apostle Paul certainly understood this to be the case. In that great resurrection chapter, 1 Cor. 15, Paul says, “if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is without foundation, and so is your faith. In addition, we are found to be false witnesses about God, because we have testified about God that He raised up Christ – whom He did not raise up… And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is worthless; you are still in your sins” (vs. 14-15, 17). Henry Thiessen agrees with the apostle when he writes: It [the resurrection] is the fundamental doctrine of Christianity. Many admit the necessity of the death of Christ who deny the importance of the bodily resurrection of Christ. But that Christ’s physical resurrection is vitally important is evident from the fundamental connection of this doctrine with Christianity. In 1 Cor. 15:12-19 Paul shows that everything stands or falls with Christ’s bodily resurrection: apostolic preaching is vain (v. 14), the apostles are false witnesses (v. 15), the Corinthians are yet in their sins (v.17), those fallen asleep in Christ have perished (v. 18), and Christians are of all men most miserable (v. 19), if Christ has not risen.1 It is difficult, if not impossible, to explain the birth of the church and its gospel message apart from the resurrection of Jesus. The whole of New Testament faith and teaching orbits about the confession and conviction that the crucified Jesus is the Son of God established and vindicated as such “by the resurrection from the dead according to the Spirit of holiness” (Rom. -

Science, Art History and the Shroud of Turin: Nicholas Allen's Research on the Iconography and Production of the Image of a Crucified Man Estelle a Mare

Science, Art History and the Shroud of Turin: Nicholas Allen's research on the iconography and production of the image of a crucified man Estelle A Mare Department of Art History and Visual Arts, University of South Africa e-mail: [email protected] There are many reasons why theologians would lical accounts have been used as evidence by hope that the faint imprint of a crucified man on those who doubt the authenticity of the Shroud the Shroud of Turin is an authentic image of of Turin as well as those who are sceptical about Jesus (fig 1). It would obviously prove that the it (Allen 1998: 4). evidence of the Gospels are true, especially that contained in the Gospel of Mark, 16: 44-6, nar The Shroud that has been kept as a relic in the 66 rating the burial of Jesus: Royal Chapel of the Cathedral of Turin since 1578 was generally believed to be the shroud And Pilate wondered if he was already dead, that Joseph of Arimathea wrapped around and summoning the centurion, he asked him Christ. This relic was declared a fake just over a whether he was already dead. And when he decade ago, but it is still venerated by millions. learned from the centurion that he was dead, he Its vicissitudes are well known. For example, it granted the body to Joseph. And he bought a sustained the unsightly scorch marks in 1532 linen shroud, and taking him down, wrapped when subjected to an accidental fire when it him in the linen shroud, and built him a tomb was kept in the Church of the Holy Chapel in which had been hewn out of the rock; and he Chambery, France, and had to be doused with rolled a stone against the door of the tomb. -

Mark 16:1-8 the Resurrection of the Great King Is Addressed

1 The Resurrection of the Great King Mark 16:1-8 Introduction: 1) I have a friend named Mike who is an atheist, or at least an agnostic. Several years ago he came over to our home to have dinner with my family and me. Later when he and I were visiting I asked him, “What is the bottom-line when it comes to Christianity?” He quickly responded and said, “That’s easy. It is the resurrection of Jesus Christ.” He then quickly added, “If the resurrection is true than so are a number of other things: 1) There is a God; 2) Jesus is that God; 3) The Bible is true; 4) Heaven and hell are real; and 5) Jesus makes the difference whether you go to one or the other.” 2) My friend Mike is right on all counts. I have often wished my seminary students and fellow theologians saw the issue as clearly. Christianity stands or falls on the historical, bodily resurrection of Jesus from the dead. No resurrection, no Christianity. In 1 Corinthians 15:17. Paul plainly writes, “And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins.” 3) In Mark 16:1-8 the resurrection of the Great King is addressed. Mark will note several evidences for the resurrection of Jesus. We will quickly examine them and then, step back and, provide a “birds-eye” view of this most critical issue of the Christian faith. We will note the possible options, examine the different theories that have been set forth, and then conclude with the massive evidence that leads us 2 to proclaim, “He is risen! He is risen indeed!” We will discover the witnesses to the resurrection are not shaky. -

FAITH & Reason

FAITH & REASON THE JOURNAL of CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE Fall 1981 | Vol. VII, No. 3 The Dispersion of the Apostles: Jude and the Shroud Warren H. Carroll In the study that follows, Warren Carroll completes his series of historical notes on the apostles by charting the activities of St. Jude and arguing his connection with the Holy Shroud. The author’s arguments frequently run counter to recent scholarly thought, and readers should pay particular atten- tion to the running commentary in the footnotes. UDE IS A SHADOWY FIGURE AMONG THE APOSTLES; IT IS OFTEN SAID THAT HE CAME to be known as the saint of recourse in apparently hopeless cases and lost causes because of all the Apostles he was the most neglected and the least known. Most historians have regarded his trail in time as faded be- yond all possibility of recovery, leaving him scarcely more than a name among the Twelve Christ personally chose to found His Church. Some of the most exciting research now being done with reference to the life of Christ and the early Church provides evidence on which a reconstruction of Jude’s apostolate may nevertheless be attempted. This is the research on the Holy Shroud of Turin-the steadily accumulating proofs of its authenticity(1) and the beginning of the unravelling of the tangled skein of its history across the centuries from the death, burial and resurrection of Christ to 1356 when unbroken knowledge of its whereabouts and character commences.(2) It is the theory of Ian Wilson, who has conducted the most thorough investigation to date into the history of the Shroud before 1356, that the image of Christ’s face which may still be seen and photographed on it was in fact the miraculous portrait of Christ long claimed as the most treasured possession of the Syrian city of Edessa (now Urfa in Turkey).(3) According to a very ancient tradition in Edessa, widely known throughout the Middle East and already set down in documentary form by the third century, King Abgar the Black of Edessa, stricken by a dread disease, sent a message to Jesus begging for a cure.