FAITH & Reason

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebuttal to Joe Nickell

Notes Lorenzi, Rossella- 2005. Turin shroud older than INQUIRER 28:4 (July/August), 69; with thought. News in Science (hnp://www.abc. 1. Ian Wilson (1998, 187) reported that the response by Joe Nickell. net.au/science/news/storics/s 1289491 .htm). 2005. Studies on die radiocarbon sample trimmings "are no longer extant." )anuary 26. from the Shroud of Turin. Thermochimica 2. Red lake colors like madder were specifically McCrone, Walter. 1996. Judgment Day for the -4CM 425: 189-194. used by medieval artists to overpaim vermilion in Turin Shroud. Chicago: Microscope Publi- Sox, H. David. 1981. Quoted in David F. Brown, depicting "blood" (Nickell 1998, 130). cations. Interview with H. David Sox, New Realities 3. Rogers (2004) does acknowledge that Nickell, Joe. 1998. Inquest on the Shroud of Turin: 4:1 (1981), 31. claims the blood is type AB "are nonsense." Latest Scientific Findings. Amherst, N.Y.: Turin shroud "older than thought." 2005. BBC Prometheus Books. News, January 27 (accessed at hnp://news. References . 2004. The Mystery Chronicles. Lexington, bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/—/2/hi/scicnce/naturc/421 Damon, P.E., et al. 1989. Radiocarbon dating of Ky.: The University Press of Kentucky. 0369.stm). the Shroud of Turin. Nature 337 (February): Rogers, Raymond N. 2004. Shroud not hoax, not Wilson, Ian. 1998. The Blood and the Shroud New 611-615. miracle. Letter to the editor, SKEPTICAL York: The Free Press. Rebuttal to Joe Nickell RAYMOND N. ROGERS oe Nickell has attacked my scien- results from Mark Anderson, his own an expert on chemical kinetics. I have a tific competence and honesty in his MOLE expert? medal for Exceptional Civilian Service "Claims of Invalid 'Shroud' Radio- Incidentally, I knew Walter since the from the U.S. -

The Expansion of Christianity: a Gazetteer of Its First Three Centuries

THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIANITY SUPPLEMENTS TO VIGILIAE CHRISTIANAE Formerly Philosophia Patrum TEXTS AND STUDIES OF EARLY CHRISTIAN LIFE AND LANGUAGE EDITORS J. DEN BOEFT — J. VAN OORT — W.L. PETERSEN D.T. RUNIA — C. SCHOLTEN — J.C.M. VAN WINDEN VOLUME LXIX THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIANITY A GAZETTEER OF ITS FIRST THREE CENTURIES BY RODERIC L. MULLEN BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mullen, Roderic L. The expansion of Christianity : a gazetteer of its first three centuries / Roderic L. Mullen. p. cm. — (Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae, ISSN 0920-623X ; v. 69) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-13135-3 (alk. paper) 1. Church history—Primitive and early church, ca. 30-600. I. Title. II. Series. BR165.M96 2003 270.1—dc22 2003065171 ISSN 0920-623X ISBN 90 04 13135 3 © Copyright 2004 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands For Anya This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................ ix Introduction ................................................................................ 1 PART ONE CHRISTIAN COMMUNITIES IN ASIA BEFORE 325 C.E. Palestine ..................................................................................... -

Orthodox Theological Faculty V. Rev. Ass. Prof. Dr. Daniel BUDA

“Lucian Blaga” UniversitySibiu “Andrei Saguna” Orthodox Theological Faculty V. Rev. Ass. Prof. Dr. Daniel BUDA SUMMARY of abilitation thesis ANTIOCH – ecclesial and theological center of multiple valences This habilitation thesis presents in summary the main results of my researches on the history and theology of Antioch as a Christian center. The main scientific principals I followed in my research were: a multi-perspective analyse of the available historical sources in order to avoid any unilateral interpretation; a coherent connection between church history and general history of Antioch; good knowledge of archaeological remains related with Antioch through visits to Antioch; direct knowledge of the present situation of the Patriarchate of Antioch due to visits in the Middle East, as well as to Antiochian communities in diaspora. The first part is dedicated to the pre-Christian history of Antioch and its importance for the knowledge of the Christian history of Antioch. I briefly presented the history of the foundation of Antioch and some essential information related with its geographical sides, the suburbia in order to understand the importance of Antioch as an urban center of the Orient before Christianity. I highlighted also the ethnic and religious diversity of the pre-Christian Antioch in order to understand the cosmopolite character of this city at the beginning of Christian era. At the end of the first part I presented the implication of this diversity for the rise of Christianity in this city: (1) Christianity did know how to -

The Letters of Saint Ignatius of Antioch

Catechetical Series: What Catholics Believe & Why THE LETTERS OF SAINT IGNATIUS OF ANTIOCH Behold The Truth Discovering the What & Why of the Catholic Faith beholdthetruth.com Bishop and Martyr Saint Ignatius was the third Bishop of the Church of Antioch, after Saint Evodius, the direct successor there of the Apostle Peter. Ignatius was also a disciple of the Apostle John; and friend to Saint Polycarp of Smyrna, another of John’s disciples. In about 107 A.D., he was arrested by the Roman soldiers and brought to Rome to be thrown to the wild beasts in the Coliseum. On the journey from Antioch to Rome, he wrote seven letters to Churches in cities he passed along the way; and these letters have been handed down to us. On the Blessed Trinity & Divinity of Christ Ignatius’ letters provide invaluable insight into the beliefs and practices of the first generation of Christians to follow the Apostles. We find evidence, for instance, of the Christian belief in the Blessed Trinity. “You are like stones for a temple of the Father,” he writes, “prepared for the edifice of God the Father, hoisted to the heights by the crane of Jesus Christ, which is the cross, using for a rope the Holy Spirit.” Letter to the Ephesians 9:1 There is evidence as well for the belief in the divinity of Christ. In the opening of his Letter to the Romans, he writes, “I wish [you] an unalloyed joy in Jesus Christ, our God.” The Importance of the Church & Sacraments Ignatius reveals a belief in the necessity of the Church and sacraments for salvation. -

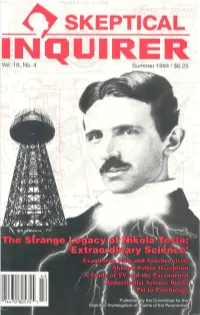

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

Constructing 'Race': the Catholic Church and the Evolution of Racial Categories and Gender in Colonial Mexico, 1521-1700

CONSTRUCTING ‘RACE’: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL CATEGORIES AND GENDER IN COLONIAL MEXICO, 1521-1700 _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Alexandria E. Castillo August, 2017 i CONSTRUCTING ‘RACE’: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL CATEGORIES AND GENDER IN COLONIAL MEXICO, 1521-1700 _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Alexandria E. Castillo August, 2017 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the role of the Catholic Church in defining racial categories and construction of the social order during and after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, then New Spain. The Catholic Church, at both the institutional and local levels, was vital to Spanish colonization and exercised power equal to the colonial state within the Americas. Therefore, its interests, specifically in connection to internal and external “threats,” effected New Spain society considerably. The growth of Protestantism, the Crown’s attempts to suppress Church influence in the colonies, and the power struggle between the secular and regular orders put the Spanish Catholic Church on the defensive. Its traditional roles and influence in Spanish society not only needed protecting, but reinforcing. As per tradition, the Church acted as cultural center once established in New Spain. However, the complex demographic challenged traditional parameters of social inclusion and exclusion which caused clergymen to revisit and refine conceptions of race and gender. -

OPUS IMPERFECTUM AUGUSTINE and HIS READERS, 426-435 A.D. by MARK VESSEY on the Fifth Day Before the Kalends of September [In

OPUS IMPERFECTUM AUGUSTINE AND HIS READERS, 426-435 A.D. BY MARK VESSEY On the fifth day before the Kalends of September [in the thirteenth consulship of the emperor 'Theodosius II and the third of Valcntinian III], departed this life the bishop Aurelius Augustinus, most excellent in all things, who at the very end of his days, amid the assaults of besieging Vandals, was replying to I the books of Julian and persevcring glorioi.islyin the defence of Christian grace.' The heroic vision of Augustine's last days was destined to a long life. Projected soon after his death in the C,hronicleof Prosper of Aquitaine, reproduccd in the legendary biographies of the Middle Ages, it has shaped the ultimate or penultimate chapter of more than one modern narrative of the saint's career.' And no wonder. There is something very compelling about the picture of the aged bishop recumbent against the double onslaught of the heretical monster Julian and an advancing Vandal army, the ex- tremity of his plight and writerly perseverance enciphering once more the unfathomable mystery of grace and the disproportion of human and divine enterprises. In the chronicles of the earthly city, the record of an opus mag- num .sed imperfectum;in the numberless annals of eternity, thc perfection of God's work in and through his servant Augustine.... As it turned out, few observers at the time were able to abide by this providential explicit and Prosper, despite his zeal for combining chronicle ' Prosper, Epitomachronicon, a. 430 (ed. Mommsen, MGH, AA 9, 473). Joseph McCabe, .SaintAugustine and His Age(London 1902) 427: "Whilst the Vandals thundered at the walls Augustine was absorbed in his great refutation of the Pelagian bishop of Lclanum, Julian." Other popular biographers prefer the penitential vision of Possidius, hita Augustini31,1-2. -

A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses

TThhee SShhrroouudd ooff TTuurriinn A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses If the truth were a mere mathematical formula, in some sense it would impose itself by its own power. But if Truth is Love, it calls for faith, for the ‘yes’ of our hearts. Pope Benedict XVI Version 4.0 Copyright 2017, Turin Shroud Center of Colorado Preface The purpose of the Critical Summary is to provide a synthesis of the Turin Shroud Center of Colorado (TSC) thinking about the Shroud of Turin and to make that synthesis available to the serious inquirer. Our evaluation of scientific, medical forensic and historical hypotheses presented here is based on TSC’s tens of thousands of hours of internal research, the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) data, and other published research. The Critical Summary synthesis is not itself intended to present new research findings. With the exception of our comments all information presented has been published elsewhere, and we have endeavored to provide references for all included data. We wish to gratefully acknowledge the contributions of several persons and organizations. First, we would like to acknowledge Dan Spicer, PhD in Physics, and Dave Fornof for their contributions in the construction of Version 1.0 of the Critical Summary. We are grateful to Mary Ann Siefker and Mary Snapp for proofreading efforts. The efforts of Shroud historian Jack Markwardt in reviewing and providing valuable comments for the Version 4.0 History Section are deeply appreciated. We also are very grateful to Barrie Schwortz (Shroud.com) and the STERA organization for their permission to include photographs from their database of STURP photographs. -

The Church in Antioch (Adventures in Acts, Session 11) Thursday, November 29, 2007

The Church in Antioch (Adventures in Acts, session 11) Thursday, November 29, 2007 Before considering the church as it is founded in Antioch (in what is now Turkey), transmitted to us in Acts 11:19 (and following), let us quickly resituate the development of the early church according to what precedes in the Acts of the Apostles: • Stephen, the deacon, is martyred in approximately 35 AD (Acts 7:54-60). • Persecution follows, and the church in Jerusalem is scattered, except the Apostles (Acts 8:11). Why were the Apostles not scattered? It is perhaps because they were of Jewish origin, and, as “Jewish Christians”, they were less of a threat to the Temple and to the Law. Their concentration in Jerusalem, of course, proves to be an obvious source of strength to the Church nascent. • Philip, the next deacon on the list after Stephen (Acts 6:5), begins his preaching (Acts 8:4-8). • Simon the magician, a prominent figure in Samaria, is converted through Peter (Acts 8:9-25). • The Ethiopian eunuch is converted through Philip (Acts 8:26-40). • Saul, the hard and ferocious persecutor, is converted through no intermediary, on his way to Damascus (Acts 9:1-19). He needed direct lightning! • At once Saul begins his preaching right there in Damascus (Acts 9:20-22), then continues in Jerusalem, where he encounters the Apostles (Acts 9:23-30). Interestingly, he returns to the place of his persecution of the Church to bring healing and reparation. Indeed, when possible, the Holy Spirit often leads us to do the same: to bring healing and reparation there where we once brought pain and division. -

Beliefs of the Original Catholic Church

Beliefs of the Original Catholic Church Could a remnant group have continuing apostolic succession? What did early Church of God leaders, Greco-Roman saints, and others record? By Bob Thiel, Ph.D. “Polycarp … in our days was an apostolic and prophetic teacher, bishop/overseer in Smyrna of the Catholic Church. For every word which he uttered from his mouth both was fulfilled and will be fulfilled.” (Martyrdom of Polycarp, 16:2) “Contend for the faith once delivered to the saints” (Jude 3, Douay-Rheims) 1 Are all professing Christian churches, other than the Roman and Eastern Orthodox Catholics, Protestant? What did the original catholic church believe? Is there a church with those original beliefs today? THIS IS A PRELIMINARY DRAFT WITH CHANGES EXPECTED. Copyright © 2021 by Nazarene Books. ISBN 978-1-64106. Book produced for the: Continuing Church of God and Successor, a corporation sole, 1036 W. Grand Avenue, Grover Beach, California, 93433 USA. This is a draft edition not expected to be published before 2021. Covers: Edited Polycarp engraving by Michael Burghers, ca 1685, originally sourced from Wikipedia. Scriptural quotes are mostly taken from Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox approved Bibles like the Challoner Douay-Rheims (DRB), Original Rheims NT of 1582 (RNT 1582), New Jerusalem Bible (NJB), Eastern Orthodox Bible (EOB), Orthodox Study Bible (OSB), New American Bible (NAB), Revised Edition (NABRE), English Standard Version-Catholic Edition (ESVCE) plus also the A Faithful Version (AFV) and some other translations. The capitalized term ‘Catholic’ most often refers to the Roman Catholic Church in quotes. The use of these brackets { } in this book means that this author inserted something, normally like a scriptural reference, into a quote. -

Sacred Heart Parish Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter 4643 Gaywood Dr

Sacred Heart Parish Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter 4643 Gaywood Dr. Fort Wayne, Indiana 46806 260-744-2519 Rev Mark Wojdelski, FSSP Pastor Parish office 260-744-2519 (In Sacred Heart school building) Email: [email protected] Web Page: sacredheartfw.org Regina Caeli Choir Teresa Smith, Director 260-353-9995 [email protected] MASS SCHEDULE Sunday 8:00 am (Low Mass) 10:00 am (Low Mass in July) Mon, & Thurs 7:30 am Tues 7:00 am Wed & Fri 6:00 pm Saturday 9:00 am Holy Days Check Bulletin SACRAMENT OF PENANCE (Confession) Friday 5:30 pm Saturday 8:30 am Sunday 7:30 & 9:30 am Any time by appointment. SACRAMENT OF MATRIMONY Active registered parishioners should contact the Pastor at least six Months in advance of the date. BAPTISM Please contact the office. LAST SACRAMENTS AND SICK CALLS Please contact the office. In an emergency requiring Extreme Unction or Viaticum please call 267-6123 SACRED HEART PARISH July 29, 2018 FORT WAYNE, INDIANA MASS INTENTIONS FOR THE WEEK Sunday Tenth Sunday after Pentecost July 29 8:00 AM Joe & Sonja Pfeiffer 10:00 AM Pro Populo Monday Feria July 30 7:30 AM James Pfeiffer Tuesday St. Ignatius of Loyola, Confessor July 31 YOUNG LADIES’ SODALITY The Young Ladies' Sodality will meet again on Friday, 7:00 AM Michael P. Buckley August 3, at 4pm in the school building. Girls ages 6 and Wednesday St. Peter in Chains up are welcome. Aug 1 NOBIS QUOQUE PECCATORIBUS (cont.) 6:00 PM Wilfrid Holscher + (Taken from Notes Made at the Conferences of Dom Prosper Guéranger) Thursday St. -

Uvic Thesis Template

The Transformation of Administrative Towns in Roman Britain by Lara Bishop BA, Saint Mary‟s University, 1997 MA, University of Wales Cardiff, 2001 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Greek and Roman Studies Lara Bishop, 2011 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee The Transformation of Administrative Towns in Roman Britain by Lara Bishop BA, Saint Mary‟s University, 1997 MA, University of Wales Cardiff, 2001 Supervisory Committee Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, (Department of Greek and Roman Studies) Supervisor Dr. J. Geoffrey Kron, (Department of Greek and Roman Studies) Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, (Department of Greek and Roman Studies) Supervisor Dr. J. Geoffrey Kron, (Department of Greek and Roman Studies) Departmental Member The purpose of this thesis is to determine whether the Roman administrative towns of Britain continued in their original Romanized form as seen in the second century AD, or were altered in their appearance and function in the fourth and fifth century, with a visible reduction in their urbanization and Romanization. It will be argued that British town life did change significantly. Major components of urbanization were disrupted with the public buildings disused or altered for other purposes, and the reduction or cessation of public services. A reduction in the population of the towns can be perceived in the eventual disuse of the extramural cemeteries and abandonment of substantial areas of settlement or possibly entire towns.