Evidence for a Resurrection Phillip H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebuttal to Joe Nickell

Notes Lorenzi, Rossella- 2005. Turin shroud older than INQUIRER 28:4 (July/August), 69; with thought. News in Science (hnp://www.abc. 1. Ian Wilson (1998, 187) reported that the response by Joe Nickell. net.au/science/news/storics/s 1289491 .htm). 2005. Studies on die radiocarbon sample trimmings "are no longer extant." )anuary 26. from the Shroud of Turin. Thermochimica 2. Red lake colors like madder were specifically McCrone, Walter. 1996. Judgment Day for the -4CM 425: 189-194. used by medieval artists to overpaim vermilion in Turin Shroud. Chicago: Microscope Publi- Sox, H. David. 1981. Quoted in David F. Brown, depicting "blood" (Nickell 1998, 130). cations. Interview with H. David Sox, New Realities 3. Rogers (2004) does acknowledge that Nickell, Joe. 1998. Inquest on the Shroud of Turin: 4:1 (1981), 31. claims the blood is type AB "are nonsense." Latest Scientific Findings. Amherst, N.Y.: Turin shroud "older than thought." 2005. BBC Prometheus Books. News, January 27 (accessed at hnp://news. References . 2004. The Mystery Chronicles. Lexington, bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/—/2/hi/scicnce/naturc/421 Damon, P.E., et al. 1989. Radiocarbon dating of Ky.: The University Press of Kentucky. 0369.stm). the Shroud of Turin. Nature 337 (February): Rogers, Raymond N. 2004. Shroud not hoax, not Wilson, Ian. 1998. The Blood and the Shroud New 611-615. miracle. Letter to the editor, SKEPTICAL York: The Free Press. Rebuttal to Joe Nickell RAYMOND N. ROGERS oe Nickell has attacked my scien- results from Mark Anderson, his own an expert on chemical kinetics. I have a tific competence and honesty in his MOLE expert? medal for Exceptional Civilian Service "Claims of Invalid 'Shroud' Radio- Incidentally, I knew Walter since the from the U.S. -

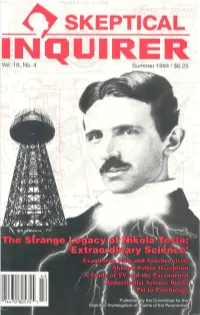

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

Evidence of Jesus(As) in India

Contents April 2002, Vol.97, No.4 Editorial Could God ignore the prayers of His prophet? . 3 The Pure Heart The role of the heart in bringing man closer to God. Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad(as) . 4 Jesus’ Survival from the Cross What the Bible tells us about this intriguing episode.: By Muzaffar Clarke – UK. 13 Is the Shroud of Turin a Medieval Photograph? - A Critical Examination of the Theory: Could the image on the famous cloth be a photograph? A photographer investigates. By Barrie M. Schwortz – USA . 22 The Israelite Origin of People of Afghanistan and the Kashmiri People – Linking the scattered tribes of Israelites with their Jewish roots. By Aziz A. Chaudhary – USA . 36 Evidence of Jesus (as) in India Historical evidence of Jesus’ migration to India.. By Abubakr Ben Ishmael Salahuddin – USA. 48 Letter to the Editor? The Catholic Church in America.. 69 Front cover photo: (© Barrie M. Schwortz) Chief Editor and Manager Chairman of the Management Board Mansoor Ahmed Shah Naseer Ahmad Qamar Basit Ahmad Bockarie Tommy Kallon Special contributors: All correspondence should Daud Mahmood Khan Amatul-Hadi Ahmad be forwarded directly to: Farina Qureshi Fareed Ahmad. The Editor Fazal Ahmad Proof-reader: Review of Religions Shaukia Mir Fauzia Bajwa The London Mosque Mansoor Saqi Design and layout: 16 Gressenhall Road Mahmood Hanif Tanveer Khokhar London, SW18 5QL Mansoora Hyder-Muneeb United Kingdom Navida Shahid Publisher: Al Shirkatul Islamiyyah © Islamic Publications, 2002 Sarah Waseem ISSN No: 0034-6721 Saleem Ahmad Malik Distribution: Tanveer Khokhar Muhammad Hanif Views expressed in this publication are not necessarily the opinions of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. -

A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses

TThhee SShhrroouudd ooff TTuurriinn A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses If the truth were a mere mathematical formula, in some sense it would impose itself by its own power. But if Truth is Love, it calls for faith, for the ‘yes’ of our hearts. Pope Benedict XVI Version 4.0 Copyright 2017, Turin Shroud Center of Colorado Preface The purpose of the Critical Summary is to provide a synthesis of the Turin Shroud Center of Colorado (TSC) thinking about the Shroud of Turin and to make that synthesis available to the serious inquirer. Our evaluation of scientific, medical forensic and historical hypotheses presented here is based on TSC’s tens of thousands of hours of internal research, the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) data, and other published research. The Critical Summary synthesis is not itself intended to present new research findings. With the exception of our comments all information presented has been published elsewhere, and we have endeavored to provide references for all included data. We wish to gratefully acknowledge the contributions of several persons and organizations. First, we would like to acknowledge Dan Spicer, PhD in Physics, and Dave Fornof for their contributions in the construction of Version 1.0 of the Critical Summary. We are grateful to Mary Ann Siefker and Mary Snapp for proofreading efforts. The efforts of Shroud historian Jack Markwardt in reviewing and providing valuable comments for the Version 4.0 History Section are deeply appreciated. We also are very grateful to Barrie Schwortz (Shroud.com) and the STERA organization for their permission to include photographs from their database of STURP photographs. -

The Prolegomena Of

HERMANN DETERING: JESUS ON THE OTHER SHORE . © 2018 Dr. Hermann Detering/Stuart G. Waugh ISBN: 9781980777960 Imprint: Independently published HERMANN DETERING JESUS O N T H E OTHER SHORE THE GNOSTIC INTERPRETATION OF EXODUS AND THE BEGINNINGS OF THE JOSHUA / JESUS CULT TRANSLATED BY: STUART G. WAUGH CONTENTS DANKSAGUNG ..................................................................... vii 1 GNOSTIC INTERPRETATION OF EXODUS ............................ 9 2 “TO THE OTHER SHORE “– BUDDHISM AND UPANISHADS ....................................................................... 24 3 THERAPEUTAE, BUDDHISM AND GNOSIS ........................ 41 4 JOSHUA, THE JORDAN AND THE BAPTISM OF JESUS ....... 62 4.1 Jesus, Joshua son of Nun, Dositheus and the question of the “right prophet” ........................................ 64 4.2 IXΘYΣ - The meaning of the fish symbol in early Christianity. ..................................................................... 69 4.3 “... who once made the sun stand still” ...................... 73 4.4 Jesus/Joshua as the Revealer of the Vine - the Didache ...................................................................... 76 4.5 Jesus/Joshua in the Epistle of Jude .............................. 84 4.6 The transfiguration of Jesus according to Mark ......... 86 4.7 “Journey ahead to the other shore” ............................ 90 4.8 Typological Interpretation of the Church Fathers ....... 92 4.9 Miriam-Mary ............................................................. 96 5 THE CHRISTIAN REDEEMER JESUS – A -

Gregory Rich Aldous Huxley Characterized Time Must Have A

“Life After Death in Huxley’s Time Must Have a Stop ” Gregory Rich Aldous Huxley characterized Time Must Have a Stop as “a piece of the Comedie Humaine that modulates into a version of the Divina Commedia ” (qtd. in Woodcock 229). To be sure, some of the dialogue includes good-natured banter, frivolous wit, and self-deprecating humor. But some of the human comedy goes further and satirizes human imperfections. For instance, the novel portrays a “jaded pasha” ( Time 67), most interested in his own pleasure, a pretentious scholarly man who talks too much ( Time 79), and a beautiful young woman who believes that the essence of life is “pure shamelessness” and lives accordingly ( Time 128). Some of the novel’s comedy is darkly pessimistic. For example, there are references to the cosmic joke of good intentions leading to disaster ( Time 194). And there are sarcastic indictments of religion, science, politics, and education ( Time 163-64). In the middle of the novel, when one of the main characters dies, the scene shifts to an after-life realm, to something like a divine-comedy realm. Both Dante’s Divine Comedy and Huxley’s Time Must Have a Stop depict an after-death realm but provide different descriptions of it. In Dante’s book, a living man takes a guided tour of hell and sees the punishments that 2 have been divinely assigned for various serious sins. In contrast, Huxley’s book depicts the experiences of a man after he has died. He seems to be in some kind of dream world, where there is no regular succession of time or fixed sense of place ( Time 222). -

By Pastor Ian Wilson

By Pastor Ian Wilson Several times over the past 50 or so years, I have been involved in the exciting adventures of pioneering a church or reviving those that had decayed to the point of closure. I had only been a Christian for a matter of a month or so when I realized that my ‘mother’ church of England could not sustain or nourish my new-found faith in Christ. I was living in an industrial and mining town in the North of England and the year was 1962. In February of that year, I had had a Damascus Road Experience with Jesus Christ while attending Bede College in Durham City. This was no gentle awakening. It was a blinding, life changing God encounter which left me with only one desire and that was to serve Christ wherever He led me. There was a man living in my town called Bill Healey. He was known as the Singing Garbage Man and it was Bill who introduced me to his church. It was a Pentecostal Assembly that had been established after revivals led by Stephen Jefferies and Smith Wigglesworth. They met in a rickety building that had once belonged to a Baptist church. The top floor had been sealed off and was the home for a flock of pigeons, but on the lower floor were organs, pews and a congregation of 25 to 30 saints. It was here that, week by week on Sundays, I enjoyed the Presence of God and the fellowship of these large-hearted saints who were filled with the Holy Ghost and the love of God. -

Science and the Shroud of Turin

Science and the Shroud of Turin © May 2015 Robert J. Spitzer, S.J., Ph. D. Magis Center of Reason and Faith Introduction The Shroud of Turin is a burial shroud (a linen cloth woven in a 3-over 1 herringbone pattern) measuring 14 ft. 3 inches in length by 3 ft. 7 inches in width. It apparently covered a man who suffered the wounds of crucifixion in a way very similar to Jesus of Nazareth. (Notice the position of the blood stains—the bold brown color—in relation to the image of the body—the fainter sepia hue—in Figure 1 below). Figure 1 The cloth has a certifiable history from 1349 when it surfaced in Lirey, France in the hands of a French nobleman – Geoffrey de Charny.1 It also has a somewhat sketchy traceable history from Jerusalem to Lirey, France – through Edessa, Turkey and Constantinople.2 This 1 This history is recounted in Appendix I (Section I) of a forthcoming book God So Loved the World: Clues to our Transcendent Destiny from the Revelation of Jesus (Ignatius Press -- coming 2016). The history is well captured in Wilson, Ian. 1978. The Shroud of Turin (New York: Doubleday). 2 This history is recounted in Appendix I of my forthcoming book God So Loved the World: Clues to our Transcendent Destiny from the Revelation of Jesus (Ignatius Press – coming 2016). There are six important sources of this history: De Gail, Paul. 1983. “Paul Vignon” in Shroud Spectrum International 1983 (6) (https://www.shroud.com/pdfs/ssi06part7.pdf). John Long 2007 (A) “The Shroud of Turin's Earlier History: Part One: To Edessa” in Bible and Spade Spring 2007 (http://www.biblearchaeology.org/post/2013/03/14/The-Shroud-of-Turins-Earlier-History-Part-One-To- Edessa.aspx). -

Copyrighted Material

25555 Text 10/7/04 8:56 AM Page 13 1 the enigma of the holy shroud The Shroud of Turin is the holiest object in Christendom. To those who believe, it is proof not only of Jesus the man, but it is also evidence of the Resurrection, the central dogma for hundreds of millions of the faithful. Regarded as the winding sheet, the burial cloth of Jesus, it is revered by many, and on the rare instances when it is displayed, the lines to view the Shroud go on for hours. The Shroud measures fourteen feet three inches long and three feet seven inches wide. It depicts the full image of a six-foot-tall man with the visible consequences of a savage beating and cruel death on the cross, in other words, crucifixion. Belief in the authenticity of the Shroud is not uni- versal. To critics it is a medieval production, created either by paint or by a more remarkable process not to be duplicated until photography was in- vented in the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, a fake. Despite the debate about the Shroud’s authenticity, it has been de- scribed as “one of the most perplexing enigmas of modern time.” This enigma has been the subject of study by an army of chemists, physicists, pathologists, biblical scholars, and art historians. Experts on textiles, pho- tography, medicine, and forensic science have all weighed in with an opin- ion.1 Had theCOPYRIGHTED image on the burial cloth MATERIALbeen that of Charlemagne or Napoleon, the debate might have proceeded along scientific lines. -

BSTS Newsletter No. 78

BRITISH SOCIETY FOR THE TURIN SHROUD NEWSLETTER 78 EDITORIAL !It has been allotted to me to follow to the Editor’s chair two truly towering figures in Shroud Studies. Their knowledge of the Shroud itself, their association with others in the field and their own primary research has amounted to a number of significant advances. Ian Wilson’s works are almost invariably the first line of approach for anybody beginning an investigation into the Shroud, and his research into the Mandylion of Edessa has stimulated a mass of concomitant investigation, both for and against his hypothesis; and Mark Guscin’s work on the Sudarium of Oviedo has opened up a whole new context for exploration, geographical, historical and cultural. !Besides these, my qualifications as an expert on the Shroud are so meagre as to be insignificant. A bit of kitchen science here, and a determination to read all the primary sources there, have given me information but not experience, a lot of knowledge, but not the intimate involvement of my predecessors. !But perhaps that’s the point, so let me introduce myself. I have been Head of Science at a Catholic School for nearly forty years, and a member of the BSTS for most of that time. For me the ‘Religion versus Science’ debate has been far from academic, and I have often found myself having to defend (or explain) their essential synthesis in the face of extremists from both sides. My first introduction to the Shroud was by reading Barbet and Vignon, and my first investigations stimulated by an almost forgotten 1982 BBC documentary, “Shroud of Jesus: Fact or Fake.” !Unlike my predecessors, whom I think are more or less committed to a pro-authenticity point of view, I myself currently incline more towards an accidental 14th century origin for the cloth now preserved in Turin. -

“The Centrality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and Its Implications For

“The Centrality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and its Implications for Missions in a Multicultural Society” INTRODUCTION: Christianity stands or falls with the bodily resurrection of Jesus. The apostle Paul certainly understood this to be the case. In that great resurrection chapter, 1 Cor. 15, Paul says, “if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is without foundation, and so is your faith. In addition, we are found to be false witnesses about God, because we have testified about God that He raised up Christ – whom He did not raise up… And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is worthless; you are still in your sins” (vs. 14-15, 17). Henry Thiessen agrees with the apostle when he writes: It [the resurrection] is the fundamental doctrine of Christianity. Many admit the necessity of the death of Christ who deny the importance of the bodily resurrection of Christ. But that Christ’s physical resurrection is vitally important is evident from the fundamental connection of this doctrine with Christianity. In 1 Cor. 15:12-19 Paul shows that everything stands or falls with Christ’s bodily resurrection: apostolic preaching is vain (v. 14), the apostles are false witnesses (v. 15), the Corinthians are yet in their sins (v.17), those fallen asleep in Christ have perished (v. 18), and Christians are of all men most miserable (v. 19), if Christ has not risen.1 It is difficult, if not impossible, to explain the birth of the church and its gospel message apart from the resurrection of Jesus. The whole of New Testament faith and teaching orbits about the confession and conviction that the crucified Jesus is the Son of God established and vindicated as such “by the resurrection from the dead according to the Spirit of holiness” (Rom. -

Shroud Spectrum International No. 41 Part 7

35 RECENTLY PUBLISHED History, Science, Theology and the Shroud; Proceedings of the St. Louis Symposium, St. Louis, Missouri, June 22-23, 1991. Edited by Aram Berard, S.J. 357 pp, black & white illus. On the spacious lawn of St. Louis Abbey, as relatives and alumni greeted friends gathering for Homecoming festivities, Brother Joe Marino, member of this Benedictine community, was introduced to a guest as "the monk all wrapped up in the Shroud". That was about the time when Bro. Joe had just begun to send out his Source Sheet, now fully developed as Sources for Information and Materials on the Shroud of Turin. Even before he began this work, the young Benedictine was already nurturing the idea of a symposium that would emphasize the theological aspects of the Holy Shroud. I mention this — laying to rest the periods of uncertainty, of opposition, of immense effort — because — with all due credit to those who sponsored his undertaking — the symposium was the realization of Bro. Joe's own idea. And since this book of the Proceedings is restricted to the publication of the papers presented, Bro. Joe Marino's name nowhere appears. The Shroud has often been discussed in the light of theology, usually with intent to bolster the Relic's "authenticity" by reference to certain Scripture passages. But we have heard very little that is new. Our little army, camped in soggy tents, tramps bravely up and down a well- trodden plot while vast unresearched fields and mysterious forests stretch to endless horizons. Invert the proposition: Can the Shroud illuminate the tenets of theology? Perhaps the first step is to scientifically demonstrate the happy obsolescence of the old conflict between science and religion.