The Shroud of Turin: a Cumulative Case for Authenticity Peter S. Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Jesus: the Shroud of Turin Episode There Is No Record of What Jesus Looked Like in the New Testament. There Are No Conte

Finding Jesus: The Shroud of Turin Episode There is no record of what Jesus looked like in the New Testament. There are no contemporary descriptions at all. However, the Bible does record how Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Jewish council and a sympathizer with Jesus, wrapped his dead body in expensive linen, and buried it in his own family tomb. In the 14th Century a shroud, bearing the image of a crucified man, surfaces in France, before eventually finding a home in Turin. Is this the very shroud that Joseph wrapped Jesus in? Is the image of the man Jesus Christ? The shroud appears to tell the whole story of Jesus’ Passion in one image – the scourging; the Crown of Thorns; carrying the cross; the Crucifixion; the spear in his side. For centuries, the shroud is a source of great controversy – many Christians believe it is genuine, but others have their doubts. In 1978 a team of scientists lead by former US Navy physicist Dr. John Jackson spend five days intensively studying the shroud, before ultimately concluding it is genuine. It isn’t a forgery or the work of an artist. But a decade later, in 1988, the shroud is subject to Radiocarbon 14 dating – scientists at three separate laboratories date the samples of the Shroud to some point between AD1260–1390. This strongly suggests the shroud is a medieval fake after all. In a final twist, the film visits the Cathedral of San Salvador, in Oviedo, Spain, where there is another burial cloth venerated as having covered the face of Jesus. -

Why Is the Turin Shroud Not Fake?

Short Communication Glob J Arch & Anthropol Volume 7 Issue 3 - December 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Giulio Fanti DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.07.555715 Why is the Turin Shroud Not Fake? Giulio Fanti* Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Padua, Italy Submission: November 23, 2018; Published: December 04, 2018 *Corresponding author: Giulio Fanti, Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Padua, Via Venezia 1 - 35131Padova, Italy Summary The Turin Shroud [1-11], the Holy Shroud or simply the Shroud (Figure 1) is the archaeological object, as well as religious, more studied in it is also religiously important because, according to the Christian tradition, it shows some traces of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. A recent paperthe world. [12] From showed a scientific why and point in which of view, sense it is the important Shroud becauseis authentic, it shows but manya double persons image still of a keep man onup statingto now thenot contrary,reproducible probably nor explainable; pushed by important Relic of Christianity based on their personal religious aspects thus publishing goal-oriented documents. their religion beliefs that arouses many logical-deductive problems. Consequently, some researchers influence the scientific aspects of the most Figure 1: The Turin Shroud (left) and its negative image (right) with zoom of the face in negative (center) with the bloodstains in positive. This work considers some debatable facts frequently offered during the discussions about the Shroud authenticity, by commenting a recent The assertions under discussion are reported here in bold for clearness. paper [13]. Many claims, apparently contrary to the Shroud authenticity, appear blind to scientific evidence and therefore require clarifications. -

Rebuttal to Joe Nickell

Notes Lorenzi, Rossella- 2005. Turin shroud older than INQUIRER 28:4 (July/August), 69; with thought. News in Science (hnp://www.abc. 1. Ian Wilson (1998, 187) reported that the response by Joe Nickell. net.au/science/news/storics/s 1289491 .htm). 2005. Studies on die radiocarbon sample trimmings "are no longer extant." )anuary 26. from the Shroud of Turin. Thermochimica 2. Red lake colors like madder were specifically McCrone, Walter. 1996. Judgment Day for the -4CM 425: 189-194. used by medieval artists to overpaim vermilion in Turin Shroud. Chicago: Microscope Publi- Sox, H. David. 1981. Quoted in David F. Brown, depicting "blood" (Nickell 1998, 130). cations. Interview with H. David Sox, New Realities 3. Rogers (2004) does acknowledge that Nickell, Joe. 1998. Inquest on the Shroud of Turin: 4:1 (1981), 31. claims the blood is type AB "are nonsense." Latest Scientific Findings. Amherst, N.Y.: Turin shroud "older than thought." 2005. BBC Prometheus Books. News, January 27 (accessed at hnp://news. References . 2004. The Mystery Chronicles. Lexington, bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/—/2/hi/scicnce/naturc/421 Damon, P.E., et al. 1989. Radiocarbon dating of Ky.: The University Press of Kentucky. 0369.stm). the Shroud of Turin. Nature 337 (February): Rogers, Raymond N. 2004. Shroud not hoax, not Wilson, Ian. 1998. The Blood and the Shroud New 611-615. miracle. Letter to the editor, SKEPTICAL York: The Free Press. Rebuttal to Joe Nickell RAYMOND N. ROGERS oe Nickell has attacked my scien- results from Mark Anderson, his own an expert on chemical kinetics. I have a tific competence and honesty in his MOLE expert? medal for Exceptional Civilian Service "Claims of Invalid 'Shroud' Radio- Incidentally, I knew Walter since the from the U.S. -

CENTRO INTERNAZIONALE DI STUDI SULLA SINDONE the Magazine of the International Center of Shroud Studies

N: 0 - gennaio 2020 SINDON LA RIVISTA DEL CISS: CENTRO INTERNAZIONALE DI STUDI SULLA SINDONE The magazine of the International Center of Shroud Studies indice 4 EDITORIALE - di Gian Maria Zaccone 6 6 IN EVIDENZA I : CISS, la storia 12 IN EVIDENZA II: L’ostensione della Sindone a Montevergine 18 NON SOLO SCIENZA: le tracce lasciate dall’imbalsamazione sulla sindone 27 IL SANGUE 34 WORKSHOP al Politecnico di Torino 18 40 La Cappella del Guarini REDAZIONE Gian Maria Zaccone Nello Balossino Enrico Simonato Paola Cappa Francesco Violi Rivista storico-scientifica e informativa SINDON 40 periodico promosso dal Centro Internazionale di Studi sulla Sindone Indirizzo: Via San Domenico, 28 – Torino Numero telefonico: +39 011 4365832 E-mail: [email protected] Sito Web: www.sindone.it 2 SINDON 3 SINDON EDITORIALE A 60 anni dalla spesso destituite di ogni fondamento non solo scientifi- co, ma anche logico. L’affastellarsi di informazioni che fondazione, Sindon provengono da svariate fonti, in particolare attraverso la rete, spesso contraddittorie ed inesatte, confondono e of- rinasce frono un panorama talora sconcertante. Inoltre le ricer- che e considerazioni che vengono pubblicate su riviste scientifiche accreditate – non moltissime per la verità – per lo più risultano di difficile fruizione e comprensione per il lettore non specializzato, e rendono necessaria una corretta divulgazione. Sindon vorrebbe portare un con- tributo alla conoscenza della Sindone, e ambisce a porsi quale punto di riferimento in questo agitato oceano di informazione. Non pubblicherà quindi articoli scientifici nuovi o inediti – che dovranno seguire i consueti canali di edizione su riviste accreditate – ma si occuperà di ren- dere comprensibili tali testi, e farà il punto sullo sviluppo della ricerca e del dibattito sulle tante questioni aperte nella multidisciplinare ricerca sindonica. -

Comparitive Study of the Sudarium of Oviedo and the Shroud of Turin

III CONGRESSO INTERNAZIONALE DI STUDI SULLA SINDONE TURIN, 5TH TO 7TH JUNE 1998 COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE SUDARIUM OF OVIEDO AND THE SHROUD OF TURIN By; Guillermo Heras Moreno, Civil Engineer, Head of the Investigation Team of the Spanish Centre for Sindonology (EDICES). José-Delfín Villalaín Blanco, DM, PhD. Professor of Forensic Medicine at the University of Valencia, Spain. Vice-President of the Investigation. Spanish Centre for Sindonology (CES). Member of the Investigation Team of the Spanish Centre for Sindonology (EDICES). Jorge-Manuel Rodríguez Almenar, Professor at the University of Valencia, Spain. Vice-President of the Spanish Centre for Sindonology (CES). Vicecoordinator of the Investigation Team of the Spanish Centre for Sindonology (EDICES). Drawings by: Margarita Ordeig Corsini, Catedrático de Dibujo, and Enrique Rubio Cobos. Spanish Centre for Sindonology (CES). Translated from the Spanish by; Mark Guscin, BA M Phil in Medieval Latin. Member of the Investigation Team of the Spanish Centre for Sindonology (EDICES). Revised by; Guillermo Heras Moreno CENTRO ESPAÑOL DE SINDONOLOGÌA. AVDA. REINO DE VALENCIA, 53. 9-16™ • E-46005-VALENCIA. Telèfono-Fax: 96- 33 459 47 • E-Mail: [email protected] ©1998 All Rights Reserved Reprinted by Permission 1 1 - INTRODUCTION. Since Monsignor Giulio Ricci first strongly suggested in 1985 that the cloth venerated in Oviedo (Asturias, Northern Spain), known as the Sudarium of Oviedo, and the Shroud of Turin had really been used on the same corpse, the separate study of each cloth has advanced greatly, according to the terminology with which scientific method can approach this hypothesis in this day and age. The paper called "The Sudarium of Oviedo and the Shroud of Turin, two complementary Relics?" was read at the Cagliari Congress on Dating the Shroud in 1990. -

The Mystical Shroud - the Images and the Resurrection an Ecumenical Perspective by James E

The Mystical Shroud - The Images and the Resurrection An Ecumenical Perspective by James E. Damon Collegamento pro Sindone Internet – March 2002 © All rights reserved* ABSTRACT Many believe the Holy Shroud of Turin is the linen burial shroud of Christ cited in the Gospels. The images of a crucified man appear on the Shroud. The identity of the man on the Shroud is unproven and the process that formed the images is unknown to modern science. For the most part, twentieth century research on the Shroud has been western in perspective and limited to the death and burial of Jesus Christ. This paper complements this perspective by adding the light mysticism and iconography of the Byzantine East to extant Shroud research. This leads to the positive identification of the Shroud man and a mystical understanding of the Resurrection that explains the image formation. This effort also demonstrates that the ancient icons of the church indicate that the Church Fathers knew of the Shroud and understood its mysteries. It also theorizes that the Shroud is the basis of the Pantocrator icon tradition in the East. The Holy Mandylion’s relationship to the Shroud is discussed. The Shroud as the “icon of icons” is discussed as a summary of the Gospel and proof of the glorious body promised to the faithful on the last day. The mystical, eschatological relationship of the Sun of Justice miracle, which occurred in Turin in 1453, to the Shroud, is also discussed. Furthermore, the mystical meaning of the 1898 positive Shroud images is briefly addressed. Finally, the paper explains the mystical means to authenticate the Shroud both spiritually and scientifically. -

Geography of the Shroud

GGeeooggrraapphhyy ooff tthhee SSiinnddoonnoollooggyy by Emanuela Marinelli and Maurizio Marinelli Collegamento pro Sindone – Rome – Italy http://www.shroud.it © 2005 All rights reserved Originally presented at the 3rd International Dallas Shroud Conference on the Shroud of Turin Dallas, Texas (USA) - September 8-11, 2005 In the past the knowledge of the Shroud in the world, in any case more devotional than scientific, was very poor. The copies of the Shroud, paintings witnesses of an ancient devotion, are about seventy. Outside Italy they are spread only in Spain in about twenty exemplars. The rest of Europe hosts other few copies in France and Portugal; only one respectively in Belgium, Malta and Switzerland. But some of them are lost. Outside Europe, only the American Continent can boast four copies (respectively in Argentina, Canada, Mexico and USA); nothing in Africa, Asia, Australia and Oceania1. Fifty years ago only two Shroud centers were in existence in the world: one in Turin, the association Cultores Sanctae Sindonis, that in 1959 was transformed in Centro Internazionale di Sindonologia2, and one in USA, the Holy Shroud Guild at Esopus, New York3. Looking at the list of the Shroud books4 on Collegamento pro Sindone website http://www.shroud.it, we can consider that only about eighty in about 700 were in existence before 1960; similar the situation for the Shroud scientific articles5 in that period, about ten in about 300. In that time, only one national congress, in 1939, and an international congress, in 1950, were held, both in Italy6; the proceedings of the national congress obviously are only in Italian and only the abstracts of the international congress were published in the proceedings, all in the original language without a translation. -

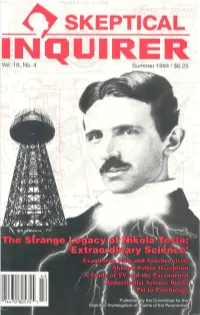

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

Proposal for C14 Dating of Charred Material Removed from the Shroud

Proposal for C14 Dating of Charred Material Removed from the Shroud by Robert A. Rucker, MS (nuclear) Rev. 1, October 15, 2018 Reviewed by Mark Antonacci, JD, Author of two books on the Shroud Thurman Cooper, MS (radiochemistry) Jonathan Prather, PhD (biomedical) Kevin N. Schwinkendorf, PhD (nuclear) Abstract In 1988 the Shroud was carbon-14 (C14) dated to 1260 to 1390 AD (Ref. 1), but other evidence (Ref. 2) is consistent with a first century date for the Shroud. To resolve this discrepancy, this proposal recommends that C14 dating be done on samples of the charred material removed from the Shroud in 2002. Nuclear analysis computer calculations based on the neutron absorption hypothesis were used to predict the measured dates for this charred material, as shown in Figure 1. If there is reasonable agreement between the measured dates and the predictions in Figure 1, i.e. about AD 3100 to AD 4800 for samples near the elbows, it would indicate that neutrons were absorbed by the linen, producing additional C14 in the Shroud. This new C14 would explain why the Shroud was C14 dated to 1260 to 1390 AD instead of the first century. Figure 1. C14 Dates Objective Predicted by MCNP To determine whether the 1988 dating of the Shroud to the Middle Ages can be explained by the neutron absorption hypothesis. Hypothesis The neutron absorption hypothesis (Ref. 2 to 4) is: 1. Neutrons were included in the burst of radiation emitted from within the body that formed the image. 2. Some of these neutrons would have been absorbed in the linen to form new C14 atoms on the Shroud. -

Who Is the Man of the Holy Shroud Tri

SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE ON THE SHROUD OF TURIN DISPLAY INCLUDES Full-size Framed Replica of the Shroud of Turin Photographic Negative of the Shroud of Turin Forensic Model of the Man of the Shroud The Shroud of Turin contains many types of scientific evidence that provide information about its history and environmental Replica Instruments of the Passion: journey. The human blood on the Shroud is Type AB. This rare blood type matches the stains on another known relic, Crucifixion Nails the Sudarium of Oviedo, which many believe to be the cloth that covered the face of Jesus as he was taken down from the Roman Lance cross. In addition to sharing the same blood type, forensic Roman Flagrum experts have identified blood stains that perfectly match on both cloths. This is significant because the Sudarium has been in Oviedo, Spain since the year 611, so any point of contact between the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo would have occurred before the seventh century. EXHIBIT TOURS Image credit American Confraternity of the Holy Shroud Exhibits tours by appointment. There are numerous To schedule a tour: specific species of plant [email protected] pollens on the Shroud that place it in or near 318-221-5296 the city of Jerusalem, Constantinople, and western Europe, all locations that align with the historical journey scholars believe to be CATHEDRAL OF accurate for the cloth. Image credit American Confraternity of the Holy Shroud PARISH AND SCHOOL sjbcathedral.org A specific soil Cathedral of St. John Berchmans sample from limestone has been identified on the Shroud of Podcast Turin – Travertine WHO IS THE MAN Aragonite – found Who is the Man of the Shroud? in only a few places manoftheshroud.wordpress.com in the Middle East, OF THE SHROUD? including the Old Apple iTunes Store City of Jerusalem. -

New Discoveries on the Sudarium of Oviedo

New Discoveries on the Sudarium of Oviedo César Barta (1) , Rodrigo Álvarez (1)(2) , Almudena Ordóñez (1)(2) , Alfonso Sánchez (1) and Jesús García (1)(2) (1) Research Team of Spanish Center of Sindonology (EDICES), Spain (2) University of Oviedo. Spain Abstract — The Sudarium of Oviedo and the Shroud of Turin are two relics attributed to Jesus Christ that show a series of II. amazing coincidences announced in the past. They lead to Previous coincidences confirm the use of both cloths on the same person. In this between Shroud and Sudarium contribution, we describe the X-ray fluorescence analysis carried out on the Sudarium. Among the chemical elements detected, the A series of definitive coincidences between the Sudarium most reliable was calcium. Being associated to soil dust, it shows of Oviedo and the Shroud of Turin have been discovered in a statistically significant higher presence in the areas with bloody various specialties of the scientific research [5][6][7][8]. Both stains. This fact allows correlating its distribution with the cloths have been used for a bearded man with moustache and anatomical features of the corpse. A large excess of calcium is longhair arranged behind in a ponytail. The Shroud shows a observed close to the tip of the nose. It is atypical to find soil dirt crucified man and the corpse of the Sudarium died in an in this zone of the anatomy, but it is just the same zone where a upright position. Moreover, in both cases, the executed man particular presence of dust was found in the Shroud. -

A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses

TThhee SShhrroouudd ooff TTuurriinn A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses If the truth were a mere mathematical formula, in some sense it would impose itself by its own power. But if Truth is Love, it calls for faith, for the ‘yes’ of our hearts. Pope Benedict XVI Version 4.0 Copyright 2017, Turin Shroud Center of Colorado Preface The purpose of the Critical Summary is to provide a synthesis of the Turin Shroud Center of Colorado (TSC) thinking about the Shroud of Turin and to make that synthesis available to the serious inquirer. Our evaluation of scientific, medical forensic and historical hypotheses presented here is based on TSC’s tens of thousands of hours of internal research, the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) data, and other published research. The Critical Summary synthesis is not itself intended to present new research findings. With the exception of our comments all information presented has been published elsewhere, and we have endeavored to provide references for all included data. We wish to gratefully acknowledge the contributions of several persons and organizations. First, we would like to acknowledge Dan Spicer, PhD in Physics, and Dave Fornof for their contributions in the construction of Version 1.0 of the Critical Summary. We are grateful to Mary Ann Siefker and Mary Snapp for proofreading efforts. The efforts of Shroud historian Jack Markwardt in reviewing and providing valuable comments for the Version 4.0 History Section are deeply appreciated. We also are very grateful to Barrie Schwortz (Shroud.com) and the STERA organization for their permission to include photographs from their database of STURP photographs.