University of Groningen Jihadism and Suicide Attacks Nanninga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combating Islamic Extremist Terrorism 1

CGT 1/22/07 11:30 AM Page 1 Combating Islamic Extremist Terrorism 1 OVERALL GRADE D+ Al-Qaeda headquarters C+ Al-Qaeda affiliated groups C– Al-Qaeda seeded groups D+ Al-Qaeda inspired groups D Sympathizers D– 1 CGT 1/22/07 11:30 AM Page 2 2 COMBATING ISLAMIC EXTREMIST TERRORISM ive years after the September 11 attacks, is the United States win- ning or losing the global “war on terror”? Depending on the prism through which one views the conflict or the metrics used Fto gauge success, the answers to the question are starkly different. The fact that the American homeland has not suffered another attack since 9/11 certainly amounts to a major achievement. U.S. military and security forces have dealt al-Qaeda a severe blow, cap- turing or killing roughly three-quarters of its pre-9/11 leadership and denying the terrorist group uncontested sanctuary in Afghanistan. The United States and its allies have also thwarted numerous terror- ist plots around the world—most recently a plan by British Muslims to simultaneously blow up as many as ten jetliners bound for major American cities. Now adjust the prism. To date, al-Qaeda’s top leaders have sur- vived the superpower’s most punishing blows, adding to the near- mythical status they enjoy among Islamic extremists. The terrorism they inspire has continued apace in a deadly cadence of attacks, from Bali and Istanbul to Madrid, London, and Mumbai. Even discount- ing the violence in Iraq and Afghanistan, the tempo of terrorist attacks—the coin of the realm in the jihadi enterprise—is actually greater today than before 9/11. -

Botnets, Cybercrime, and Cyberterrorism: Vulnerabilities and Policy Issues for Congress

Order Code RL32114 Botnets, Cybercrime, and Cyberterrorism: Vulnerabilities and Policy Issues for Congress Updated January 29, 2008 Clay Wilson Specialist in Technology and National Security Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Botnets, Cybercrime, and Cyberterrorism: Vulnerabilities and Policy Issues for Congress Summary Cybercrime is becoming more organized and established as a transnational business. High technology online skills are now available for rent to a variety of customers, possibly including nation states, or individuals and groups that could secretly represent terrorist groups. The increased use of automated attack tools by cybercriminals has overwhelmed some current methodologies used for tracking Internet cyberattacks, and vulnerabilities of the U.S. critical infrastructure, which are acknowledged openly in publications, could possibly attract cyberattacks to extort money, or damage the U.S. economy to affect national security. In April and May 2007, NATO and the United States sent computer security experts to Estonia to help that nation recover from cyberattacks directed against government computer systems, and to analyze the methods used and determine the source of the attacks.1 Some security experts suspect that political protestors may have rented the services of cybercriminals, possibly a large network of infected PCs, called a “botnet,” to help disrupt the computer systems of the Estonian government. DOD officials have also indicated that similar cyberattacks from individuals and countries targeting economic, -

Vigilantism V. the State: a Case Study of the Rise and Fall of Pagad, 1996–2000

Vigilantism v. the State: A case study of the rise and fall of Pagad, 1996–2000 Keith Gottschalk ISS Paper 99 • February 2005 Price: R10.00 INTRODUCTION South African Local and Long-Distance Taxi Associa- Non-governmental armed organisations tion (SALDTA) and the Letlhabile Taxi Organisation admitted that they are among the rivals who hire hit To contextualise Pagad, it is essential to reflect on the squads to kill commuters and their competitors’ taxi scale of other quasi-military clashes between armed bosses on such a scale that they need to negotiate groups and examine other contemporary vigilante amnesty for their hit squads before they can renounce organisations in South Africa. These phenomena such illegal activities.6 peaked during the1990s as the authority of white su- 7 premacy collapsed, while state transfor- Petrol-bombing minibuses and shooting 8 mation and the construction of new drivers were routine. In Cape Town, kill- democratic authorities and institutions Quasi-military ings started in 1993 when seven drivers 9 took a good decade to be consolidated. were shot. There, the rival taxi associa- clashes tions (Cape Amalgamated Taxi Associa- The first category of such armed group- between tion, Cata, and the Cape Organisation of ings is feuding between clans (‘faction Democratic Taxi Associations, Codeta), fighting’ in settler jargon). This results in armed groups both appointed a ‘top ten’ to negotiate escalating death tolls once the rural com- peaked in the with the bus company, and a ‘bottom ten’ batants illegally buy firearms. For de- as a hit squad. The police were able to cades, feuding in Msinga1 has resulted in 1990s as the secure triple life sentences plus 70 years thousands of displaced persons. -

Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Studying Jihadism 2 3 4 5 6 Volume 2 7 8 9 10 11 Edited by Rüdiger Lohlker 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. 37 38 Editorial Board: Farhad Khosrokhavar (Paris), Hans Kippenberg 39 (Erfurt), Alex P. Schmid (Vienna), Roberto Tottoli (Naples) 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Rüdiger Lohlker (ed.) 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jihadism: Online Discourses and 8 9 Representations 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 With many figures 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 & 37 V R unipress 38 39 Vienna University Press 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; 24 detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

Legalised Pedigrees: Sayyids and Shiʽi Islam in Pakistan

Legalised Pedigrees: Sayyids and Shiʽi Islam in Pakistan SIMON WOLFGANG FUCHS Abstract This article draws on a wide range of Shiʽi periodicals and monographs from the s until the pre- sent day to investigate debates on the status of Sayyids in Pakistan. I argue that the discussion by reform- ist and traditionalist Shiʽi scholars (ʽulama) and popular preachers has remained remarkably stable over this time period. Both ‘camps’ have avoided talking about any theological or miracle-working role of the Prophet’s kin. This phenomenon is remarkable, given the fact that Sayyids share their pedigree with the Shiʽi Imams, who are credited with superhuman qualities. Instead, Shiʽi reformists and traditionalists have discussed Sayyids predominantly as a specific legal category. They are merely entitled to a distinct treatment as far as their claims to charity, patterns of marriage, and deference in daily life is concerned. I hold that this reductionist and largely legalising reading of Sayyids has to do with the intense competition over religious authority in post-Partition Pakistan. For both traditionalist and reformist Shiʽi authors, ʽulama, and preachers, there was no room to acknowledge Sayyids as potential further competitors in their efforts to convince the Shiʽi public about the proper ‘orthodoxy’ of their specific views. Keywords: status of Sayyids; religious authority in post-Partition Pakistan; ahl al-bait; Shiʻi Islam Bashir Husain Najafi is an oddity. Today’s most prominent Pakistani Shiʽi scholar is counted among Najaf’s four leading Grand Ayatollahs.1 Yet, when he left Pakistan for Iraq in in order to pursue higher religious education, the deck was heavily stacked against him. -

Questions Answers 1 What Was the Famous Tribe in Mecca? Quraish 2

# Questions Answers 1 What was the famous tribe in Mecca? Quraish 2 Name the parents of Muhammad (s)? Abdullah and Amina 3 Who was Abdul Muttalib? The grandfather of Mohammad(s) 4 What day was Muhammad (s) born? 12th of Rabiul Awwal the year of elephants 5 Where was Muhammad (s) born? City of Mecca 6 How many brothers and sisters did Muhammad (s) Mohammad(s) had no have? siblings. He was the only child 7 Can you name any significant event before Abraha’s elephant army Muhammad (s) was born? 8 Who was the lady who nursed him and what tribe Haleema Sadiya tribe of did she belong to? Sa’ad bin Bakr of Hawazin 9 What important event took place with the nurse? Jibrael cleansed his heart with Zam Zam water 10 Who took care of Muhammad (s) when his Abu Talib, his uncle grandfather passed away? 11 At what age was Muhammad (s) when his mother He was six years old passed away? 12 Name the place where Amina passed away? Abwa located between Mecca and Madina 13 Who brought Muhammad (s) to Mecca? Ume-Aimen 14 What was Muhammad (s) age when his Eight years old grandfather passed away? 15 Which city did Mohammad(s) go for business? Sham (Syria) 16 What profession was Muhammad (s) involved in? business 17 When did Mohammad(s) father pass away? Before Mohammad(s) birth 18 Who was Muhammad (s) first wife? Khadija (r) 19 What was Muhammad (s) wife impressed by? His honesty 20 Who did Muhammad (s) marriage ceremony? Abu Talib 21 Name all the children the couple had? Zainab, Ruqaiya, Ume- Kulthoom, Fatima, Qasim and Abdullah 22 Who was the mother of Ibrahim -

Īmān, Islām, Taqwā, Kufr, Shirk, and Nifāq: Definitions, Examples and Impacts on Human Life

IIUC Studies 14(2) DOI: https://doi.org/10.3329/iiucs.v14i2.39882 Īmān, Islām, taqwā, kufr, shirk, and nifāq: Definitions, examples and impacts on human life Md. Mahmudul Hassan Centre for University Requirement Courses (CENURC) International Islamic University Chittagong (IIUC), Bangladesh Abstract The Holy Qur‟an encompasses the comprehensive code for mankind to live a rewarding life in this world, to rescue from the Jahannam and to enter the Jannah in the Hereafter. Īmān, Islām, taqwā, kufr, shirk, and nifāq are, the six significant terms, used in the Noble Qur‟an frequently. All of them represent the characteristics of human beings. The possessors of these characters will go to their eternal destination; the Jannah or Jahannam. The Jannah is the aftermath of īmān, Islam and taqwā. On the other hand, kufr, shirk, and nifāq lead to the Jahannam. This study intends to present the definitions and examples of these six terms according to the Qur‟anic statement, and then shed light on the impact of each character on human life quoting the evidence from the Holy Qur‟an and the Traditions of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). The possessors of these six remarkable terms are entitled successively as mu'min, muslim, muttaqī to be rewarded Jannah and kafīr, mushrik, and munāfiq to be punished in Jahannam. Keywords The Comprehensive code, Eternal destination, Qur‟anic terms Paper type Literature review 1. Introduction Īmān, Islām, and taqwā are three positive divine instructions whereas, kufr, shirk, and nifāq are three negative characteristics which are strongly prohibited by divine decrees. The Jannah and the Jahannam are two eternal destinations of humanities in the Hereafter. -

And When the Believers Saw the Confederates Abu Hasan Al-Muhajir June 12, 2017

And When The Believers Saw The Confederates Abu Hasan al-Muhajir June 12, 2017 [Please note: Images may have been removed from this document. Page numbers have been added.] All praise is due to Allah, who said in His Book, “And when the believers saw the confederates, they said, ‘This is what Allah and His Messenger had promised us, and Allah and His Messenger spoke the truth.’ And it increased them only in faith and acceptance” (Al-Ahzab 22). I bear witness that there is no god but Allah, alone and without partner, and I bear witness that Muhammad is His slave and messenger, whom Allah sent with the sword before the Hour as a bringer of glad tidings and a warner, and as a caller to Allah with His permission and an illuminating lamp. Through him Allah established the proof, clarified the correct path, and brought triumph to the true religion. He waged jihad in the path of Allah until the religion became upright by him. May Allah’s blessings and abundant peace be upon him, and upon his family. As for what follows: Indeed, from the sunnah (established way) of Allah which neither alters nor changes is that He tests His believing slaves, as He has informed us with His statement, “Do the people think that they will be left to say, ‘We believe’ and they will not be tried? But We have certainly tried those before them, and Allah will surely make evident those who are truthful, and He will surely make evident the liars” (Al-Ankabut 2-3). -

Preventing Violent Extremism in Kyrgyzstan

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Jacob Zenn and Kathleen Kuehnast This report offers perspectives on the national and regional dynamics of violent extremism with respect to Kyrgyzstan. Derived from a study supported by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) to explore the potential for violent extremism in Central Asia, it is based on extensive interviews and a Preventing Violent countrywide Peace Game with university students at Kyrgyz National University in June 2014. Extremism in Kyrgyzstan ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jacob Zenn is an analyst on Eurasian and African affairs, a legal adviser on international law and best practices related to civil society and freedom of association, and a nonresident research Summary fellow at the Center of Shanghai Cooperation Organization Studies in China, the Center of Security Programs in Kazakhstan, • Kyrgyzstan, having twice overthrown autocratic leaders in violent uprisings, in 2005 and again and The Jamestown Foundation in Washington, DC. Dr. Kathleen in 2010, is the most politically open and democratic country in Central Asia. Kuehnast is a sociocultural anthropologist and an expert on • Many Kyrgyz observers remain concerned about the country’s future. They fear that underlying Kyrgyzstan, where she conducted field work in the early 1990s. An adviser on the Central Asia Fellows Program at the socioeconomic conditions and lack of public services—combined with other factors, such as Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington drug trafficking from Afghanistan, political manipulation, regional instability in former Soviet University, she is a member of the Council on Foreign Union countries and Afghanistan, and foreign-imported religious ideologies—create an envi- Relations and has directed the Center for Gender and ronment in which violent extremism can flourish. -

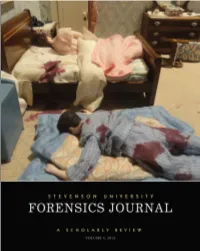

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death Stephanie Witt

School of Graduate and Professional Studies 100 Campus Circle, Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 1-877-468-6852 accelerate.stevenson.edu STEVENSON UNIVERSITY FORENSICS JOURNAL VOLUME 4 EDITORIAL BOARD EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Carolyn Hess Johnson, Esq. PUBLISHER Carolyn Hess Johnson, Esq. EDITORS Abigail Howell Stephanie Witt COVER PHOTO Bruce Goldfarb Assistant to the Chief Medical Examiner, Maryland DESIGN & LAYOUT Chip Burkey Cassandra Bates Stevenson University Marketing and Public Relations Office Copyright © 2013, author(s) and Stevenson University Forensics Journal. No permission is given to copy, distribute or reproduce this article in any format without prior explicit written permission from the article’s author(s) who hold exclusive rights to impose usage fee or royalties. FORENSICS JOURNAL Welcome to our fourth annual Stevenson University Forensics Journal. This year, as always, we bring fresh voices and perspectives from all aspects and areas of the field. I am pleased to note that a new section has been added this year, highlighting the process of library research in the vast field of Forensic Studies. Our Stevenson University librarians bring the research pro- cess into the twenty-first century by showcasing a variety of on-line resources available to researchers. Also of note is the connection between our cover photo and the interview conducted with Dr. David Fowler, Chief Medical Examiner for the State of Maryland. Assistant Editor Stephanie Witt joins the Journal as a contributor to explain the fascinating Nutshell Series of Unexplained Deaths. We are privileged this year to have the Honorable Lynne A. Battaglia providing her insights into the Court’s perspective on the prominent role of forensic evidence in modern litigation. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Beining and Evans

THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES IMES CAPSTONE PAPER SERIES IS A BOMBER JUST A BOMBER? A MULTILEVEL ANALYSIS OF WOMEN SUICIDE BOMBERS1 CARA BEINING KARI EVANS APRIL 2014 THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES THE ELLIOTT SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY © OF CARA BEINING AND KARI EVANS, 2014 Beining and Evans TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………….. 3 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………. 4 A Note on Terms……………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Defining the Problem…………………………………………………………………………... 9 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………….. 12 I. THE GLOBAL TREND…………………………………………………………………….. 17 II. ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS………………………………………………………….. 22 Palestine………………………………………………………………………………………. 25 Iraq……………………………………………………………………………………………. 28 The Role of the Environment…………………………………………………………………. 30 III. ORGANIZATIONAL LEVEL…………………………………………………………… 32 Hamas…………………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Al-Qaeda in Iraq………………………………………………………………………………. 40 Role of the Organization……………………………………………………………………… 46 IV: INDIVIDUAL LEVEL……………………………………………………………………. 49 Examples from Palestine……………………………………………………………………… 52 Examples from Iraq…………………………………………………………………………… 56 Role of the Individual………………………………………………………………………….58 V. CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………………... 60 The Big Picture………………………………………………………………………………...60 Recommendations…………………………………………………………………………….. 62 APPENDIX I ………………………………..…………………………………………………. 73 APPENDIX II…………………….…………………………………………………………….. 79 APPENDIX III…………………………….……………………………………………………