Updates Clinical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antidepressants for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

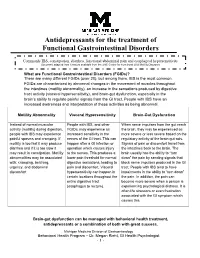

Antidepressants for the treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Commonly IBS, constipation, diarrhea, functional abdominal pain and esophageal hypersensitivity Document adapted from literature available from the UNC Center for Functional GI & Motility Disorders What are Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGIDs)? There are many different FGIDs (over 20), but among them, IBS is the most common. FGIDs are characterized by abnormal changes in the movement of muscles throughout the intestines (motility abnormality), an increase in the sensations produced by digestive tract activity (visceral hypersensitivity), and brain-gut dysfunction, especially in the brain’s ability to regulate painful signals from the GI tract. People with IBS have an increased awareness and interpretation of these activities as being abnormal. Motility Abnormality Visceral Hypersensitivity Brain-Gut Dysfunction Instead of normal muscular People with IBS, and other When nerve impulses from the gut reach activity (motility) during digestion, FGIDs, may experience an the brain, they may be experienced as people with IBS may experience increased sensitivity in the more severe or less severe based on the painful spasms and cramping. If nerves of the GI tract. This can regulatory activity of the brain-gut axis. motility is too fast it may produce happen after a GI infection or Signals of pain or discomfort travel from diarrhea and if it is too slow it operation which causes injury the intestines back to the brain. The may result in constipation. Motility to the nerves. This produces a brain usually has the ability to “turn abnormalities may be associated lower pain threshold for normal down” the pain by sending signals that with: cramping, belching, digestive sensations, leading to block nerve impulses produced in the GI urgency, and abdominal pain and discomfort. -

Managing Cancer Pain

The British Pain Society's Managing cancer pain - information for patients From the British Pain Society, supported by the Association of Palliative Medicine and the Royal College of General Practitioners January 2010 To be reviewed January 2013 2 Cancer Pain Management Published by: The British Pain Society 3rd floor Churchill House 35 Red Lion Square London WC1R 4SG Website: www.britishpainsociety.org ISBN: 978-0-9551546-8-3 © The British Pain Society 2010 Information for Patients 3 Contents Page What can be done for people with cancer pain 4 Understanding cancer pain 4 Knowing what to expect 6 Options for pain control – most pain can be controlled 6 Coping with cancer pain 8 Describing pain – communicating with your doctors 9 Talking to others with cancer pain 12 Finding help managing cancer pain 12 References 12 Methods 12 Competing Interests 13 Membership of the group and expert contributors 13 4 Cancer Pain Management What can be done for people with cancer pain? There are medicines and expertise available that can help to control cancer pain. However, surveys show that cancer pain is still poorly controlled in many cases. As a result, patients must know what is available, what they have a right to and how to ask for it. Cancer itself and the treatments for cancer, including both medicines and surgery, can cause pain. Treatments can be directed either at the cause of the pain (for example, the tumour itself) or at the pain itself. Understanding cancer pain Cancer pain can be complicated, involving pain arising from inflammation (swelling), nerve damage and tissue damage from many sites around the body. -

Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gutlbrain Interaction): a Rome Foundation Working Team Report Douglas A

Gastroenterology 2018;154:1140–1171 SPECIAL REPORT Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of GutLBrain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report Douglas A. Drossman,1,2 Jan Tack,3 Alexander C. Ford,4,5 Eva Szigethy,6 Hans Törnblom,7 and Lukas Van Oudenhove8 1Center for Functional Gastrointestinal and Motility Disorders, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; 2Center for Education and Practice of Biopsychosocial Care and Drossman Gastroenterology, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; 3Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 4Leeds Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom; 5Leeds Gastroenterology Institute, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds, United Kingdom; 6Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 7Departments of Internal Medicine and Clinical Nutrition, Institute of Medicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; and 8Laboratory for BrainÀGut Axis Studies, Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium BACKGROUND & AIMS: Central neuromodulators (antide- summary information and guidelines for the use of central pressants, antipsychotics, and other central nervous neuromodulators in the treatment of chronic gastrointestinal systemÀtargeted medications) are increasingly used for treat- symptoms and FGIDs. Further studies are needed to confirm ment -

Abdominal Visceral Pain: Clinical Aspect*

Rev Dor. São Paulo, 2013 out-dez;14(4):311-4 ARTIGO DE REVISÃO Abdominal visceral pain: clinical aspects* Dor visceral abdominal: aspectos clínicos Telma Mariotto Zakka1, Manoel Jacobsen Teixeira1, Lin Tchia Yeng1 *Recebido do Centro Interdisciplinar de Dor do Hospital de Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina / Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo, SP, Brasil. ABSTRACT CONTEÚDO: Como as doenças viscerais podem determinar dores de vários tipos e, habitualmente, desafiam os médicos no seu diagnós- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: Abdomen is the most fre- tico e tratamento, os autores descreveram de forma prática, as carac- quent site for acute or chronic painful syndromes, for referred pain terísticas dolorosas e as associações com as doenças mais incidentes. from distant structures or for pain caused by systemic injuries. Ab- CONCLUSÃO: O tratamento interdisciplinar com a associação das dominal visceral pain is induced by hollow viscera or parenchymal medidas farmacológicas aos procedimentos de medicina física e rea- viscera walls stretching or by peritoneal stretching. Complex diag- bilitação e ao acompanhamento psicológico diminui o sofrimento e nosis and treatment have motivated this study. Patients with chronic as incapacidades e melhora a qualidade de vida. abdominal pain are usually undertreated and underdiagnosed. The Descritores: Dor abdominal, Dor miofascial, Dor visceral, Trata- interdisciplinary treatment aims at minimizing patients’ distress, re- mento interdisciplinar. lieving pain and improving their quality of life. CONTENTS: Since visceral diseases may determine pain of different INTRODUÇÃO types and, usually, challenge physicians with regard to their diagnosis and treatment, the authors have described in a practical way painful A dor visceral pode decorrer por tensão ou estiramento da parede characteristics and associations with more common diseases. -

Clinical Evidence on Visceral Pain. Systematic Review Evidência Clínica Sobre Dor Visceral

Rev Dor. São Paulo, 2017 jan-mar;18(1):65-71 REVIEW ARTICLE Clinical evidence on visceral pain. Systematic review Evidência clínica sobre dor visceral. Revisão sistemática Durval Campos Kraychete1, José Tadeu Tesseroli de Siqueira2, João Batista Garcia3, Rioko Kimiko Sakata4, Ângela Maria Sousa5, Daniel Ciampi de Andrade6, Telma Regina Mariotto Zakka7, Manoel Jacobsen Teixeira7 and Diretoria da Sociedade Brasileira para o Estudo da Dor de 2015 DOI 10.5935/1806-0013.20170014 ABSTRACT RESUMO BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: Visceral pain is in- JUSTIFICATIVA E OBJETIVOS: A dor visceral é causada por duced by abnormalities of organs such as stomach, kidneys, anormalidades de órgãos como o estômago, rim, bexiga, vesícula bladder, gallbladder, intestines and others and includes disten- biliar, intestinos ou outros e inclui distensão, isquemia, inflama- sion, ischemia, inflammation and mesenteric traction. It is re- ção e tração do mesentério. É responsável por incapacidade física sponsible for physical and psychic incapacity, absenteeism and e psíquica, absenteísmo do trabalho e má qualidade de vida. O poor quality of life. This study aimed at discussing major aspects objetivo deste estudo foi discutir os principais aspectos da dor of visceral pain with regard to prevalence, etiology and diagnosis. visceral relacionados a prevalência, etiologia e diagnóstico. CONTENTS: According to Evidence-Based Medicine concepts, CONTEÚDO: Foram revisados segundo os preceitos da Medic- visceral pain etiology, diagnosis and prognosis were reviewed in ina Baseada em Evidência os enfoques etiológicos, diagnóstico LILACS, EMBASE and Pubmed databases. Therapeutic stud- e prognóstico da dor visceral nas bases de indexações biomédi- ies were not selected. The following terms were used as search cas, LILACS, EMBASE e Pubmed. -

Milnacipran, a Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor: a Novel Treatment for Fibromyalgia

Drug Evaluation Milnacipran, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor: a novel treatment for fibromyalgia Milnacipran hydrochloride is a serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake inhibitor that was recently approved by the US FDA for the treatment of fibromyalgia (FM). Evidence has accumulated suggesting that, in animal models, milnacipran may exert pain-mitigating influences involving norepinephrine- and serotonin-related processes at supraspinal, spinal and peripheral levels in pain transmission. Milnacipran has demonstrated efficacy for the reduction of pain as well as improvements in global assessments of well-being and functional capacity among treated FM patients. Its role in addressing comorbidities associated with FM, including visceral pain and migraine, has, as yet, to be investigated. Milnacipran may be of special interest for use in patients for whom hepatic dysfunction precludes the use of other agents, for example, duloxetine. It has a negligible influence on cytochrome metabolism, and therefore may be of particular benefit in patients requiring multiple concurrently prescribed medications. Milnacipran may comprise a reasonable option in the armamentarium of treatments available to manage FM. KEYWORDS: antidepressants n chronic pain n fibromyalgian milnacipran n serotonin Raphael J Leo and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine and Fibromyalgia (FM) is a syndrome characterized Several pharmacological approaches have Biomedical Sciences, by chronic, widespread musculoskeletal pain and been advocated for the treatment of FM. State University of New York at tenderness. The prevalence of FM in the general Because of their impact on these presump- Buffalo, Erie County Medical population is estimated to be 2–4%; it tends to tive pathophysiologic processes, antidepres- Center, 462 Grider Street, show a female predilection, and increases with sants have frequently been advocated for Buffalo, NY 14215, USA age [1,2]. -

Visceral Pain

9/10/2015 Visceral Pain Nevenka Krcevski Skvarc University Clinical Center Maribor, Maribor, Slovenia Visceral pain • Definition Pain arising from the internal organs of the body: • Heart, great vessels, and perivascular structures (e.g. lymph nodes) • Airway structures (pharynx, trachea, bronchi, lungs, pleura) • Gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum) • Upper abdominal structures (liver, gallbladder, billiary tree, pancreas, spleen) • Urological structures (kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, urethra) • Reproductive organs (uterus, ovaries, vagina, testes, vas deferens, prostate) • Omentum, visceral peritoneum 1 9/10/2015 Key points • General characteristics of visceral pain • Burden of visceral pain • Visceral nociception • General clinical features • Chronic visceral pain • Functional syndromes Visceral pain: organic or functional nociceptive inflammatory neuropathic mixed Various etiology 4 the most frequent: Functional Inflammation syndromes Infection Gallstones Functional abdominal pain: Disorders of mechanical Pancreatitis 0,5%- 2% function Appendicitis IBS: 10% - 20% Tumors Diverticulitis Functional dyspepsia 20% - 30% Disorders of neural Functional gallbladder function disorders: 7,6% - 20,7% Ischemic disorders Painful bladder syndrome: 3% Idiopathic Cardiac pain syndrome : 3% 2 9/10/2015 Visceral (abdominal) pain: from transitory to chronic Catastrophic onset Colicky Severity Short to long duration Subside spontaneously Time General characteristics of pain due to visceral pathology True visceral -

Neurobiology of Visceral Pain

Neurobiology of Visceral Pain Definition Pain arising from the internal organs of the body: • Heart, great vessels, and perivascular structures (e.g., lymph nodes) • Airway structures (pharynx, trachea, bronchi, lungs, pleura) • Gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum) • Upper-abdominal structures (liver, gallbladder, biliary tree, pancreas, spleen) • Urological structures (kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, urethra) • Reproductive organs (uterus, ovaries, vagina, testes, vas deferens, prostate) • Omentum, visceral peritoneum Clinical Features of Visceral Pain Key features associated with pain from the viscera include diffuse localization, an unreliable association with pathology, and referred sensations. Strong autonomic and emotional responses may be evoked with minimal sensation. Referred pain has two components: (1) a localization of the site of pain generation to somatic tissues with nociceptive processing at the same spinal segments (e.g., chest and arm pain from cardiac ischemia) and (2) a sensitization of these segmental tissues (e.g., kidney stones may cause the muscles of the lateral torso to become tender to palpation). These features are in contrast to cutaneous pain, which is well localized and features a graded stimulus-response relationship. Anatomy of Neurological Structures Pathways for visceral sensation are diffusely organized both peripherally and centrally. Primary afferent nerve fibers innervating viscera project into the central nervous system via three pathways: (1) in the vagus nerve and its branches; (2) within and alongside sympathetic efferent fiber pathways (sympathetic chain and splanchnic branches, including greater, lesser, least, thoracic, and lumbar branches); and (3) in the pelvic nerve (with parasympathetic efferents) and its branches. Passage through the peripheral ganglia occurs with potential synaptic contact (e.g., celiac, superior mesenteric, and hypogastric nerves). -

Gastrointestinal Pain

GASTROINTESTINALPRIMEVIEW PAIN For the Primer, visit doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0135-7 MANAGEMENT Gastrointestinal (GI) pain — a form of MECHANISMS Visceral visceral pain — is a common symptom primary of some GI disorders, such as Crohn’s afferents terminate In some cases, treating the underlying cause disease, chronic pancreatitis and at several levels of GI pain is sufficient for pain reduction. irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Acute throughout the spinal However, pain-specific management can be pain is cord, which can, in part, required for some disorders, such as acute predominantly explain the diffuse pancreatitis. Although no pharmacological DIAGNOSIS conveyed to the spinal PCVWTGQH)+|RCKP therapies have been approved specifically for cord via visceral afferent fibres, specifically via GI pain, clinicians often use therapies that are GI pain is often initially poorly c-fibres and Aδ fibres, 8CICNȮDTGU approved for musculoskeletal or neuropathic localized, although the pain following which, the pain pain, such as NSAIDs, acetaminophen, presentation can change over signal is transmitted gabapentin, tricyclic antidepressants and time. For example, pain in acute to the brain serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors. appendicitis is intially diffuse, but Sympathetic Of note, NSAIDs should be administered localizes to a specific region of the ȮDTGU Spinal with proton pump inhibitors in patients with abdomen (McBurney’s point) during later Enteric ȮDTGU GI disorders, owing to their effects on the stages of disease. In addition, GI pain can be ȮDTGU gut. Opioids can be used for severe GI pain referred to somatic structures, such as muscle but should be used with extreme caution or skin, and can be accompanied by autonomic owing to the high risk of dependence. -

Differential Diagnosis of Chest Pain

This presentation is the property of the Milwaukee County EMS Education Center. Any reproduction or use of this presentation without expressed permission is prohibited. Andrew Irzyk 2015 MCEMS Differential Diagnosis of Chest Pain There are literally dozens of illnesses, injuries and conditions that can cause chest pain. Knowing common signs, symptoms and patient presentations can help you differentiate between different kinds of chest pain. Bottom Line: If you are ever not sure what kind of chest pain you are dealing with, treat it as cardiac and call medical control. Differential Diagnosis of Chest Pain Common Causes of Chest Pain Cardiovascular: Respiratory: ischemia (AMI or PE (pulmonary angina) embolism) pericarditis (irritation pneumothorax of pericardium) pneumonia thoracic aortic pleural irritation dissection hyperventilation (anxiety) Differential Diagnosis of Chest Pain Common Causes of Chest Pain Gastrointestinal: Musculoskeletal: cholecystitis (gall chest wall syndrome bladder/gallstones) (inflamed chest wall) pancreatitis costochondritis (inflamed hiatal hernia (part of stomach pushes through rib cartilage) diaphragm) herpes zoster (shingles) esophageal disease/GERD chest wall trauma peptic ulcers chest wall tumors dyspepsia (indigestion) Non Cardiac Chest Pain Pulmonary Musculoskeletal Pneumonia Costochondritis Pleuritis Cervical Disk Disease Pneumothorax Rib Fracture Pulmonary Embolism Intercostal Muscle Cramp Tumor Other Gastrointestinal Herpes Zoster GERD Disorders of the Breast Esophageal -

Assessment and Management of Cancer Pain

3601_e23_p493-535 2/19/02 9:05 AM Page 493 23 Assessment and Management of Cancer Pain SURESH K. REDDY AND C. STRATTON HILL, JR. PREVALENCE OF CANCER PAIN that pain is only one aspect of suffering, it is often a major one. Comprehensive management of the can- It is estimated that from 30% to 50% of patients ac- cer patient with pain requires that all of the factors tively undergoing cancer therapy and from 60% to associated with the quality of life of the person as a 90% of patients with advanced cancer have pain (Fo- whole be considered. ley, 1979; Bonica, 1990; Twycross and Fairfield, 1982; World Health Organization, 1986; Levin et al., 1985). Approximately 50% of children in an inpatient UNDERTREATMENT OF CANCER PAIN pediatric cancer center and about 25% of outpatients experience pain (Miser et al., 1987). The World It is a sad fact that pain is not satisfactorily managed Health Organization Cancer Pain Relief Program in- for many cancer patients. For example, in one pub- dicates that approximately 5 million people world- lished study, 1308 patients were surveyed at 54 treat- wide suffer from cancer-related pain on a daily ba- ment sites participating in the Eastern Cooperative sis, and fully 25% of them die at home or in a hospital Oncology Group to evaluate the prevalence of pain without relief (World Health Organization, 1990). and the adequacy of its treatment (Cleeland et al., It is important to assess the effects of pain on the 1994). In this study, 67% of patients reported daily quality of life in multidimensional terms, and the de- pain and took analgesics daily. -

3 CHEST PAIN Emerg Med J: First Published As 10.1136/Emj.2003.013938 on 26 February 2004

The ABC of community emergency care 3 CHEST PAIN Emerg Med J: first published as 10.1136/emj.2003.013938 on 26 February 2004. Downloaded from C Laird, P Driscoll, J Wardrope 226 Emerg Med J 2004;21:226–232. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.013938 hest pain is the commonest reason for 999 calls and accounts for 2.5% of out of hours calls. Of patients taken to hospital about 10% will have an acute myocardial infarction (AMI). CEvidence suggests that up to 7.5% of these will be missed on first presentation. There are a number of other life threatening conditions, which can present as chest pain and must not be overlooked. The objectives of this article are therefore to provide a safe and comprehensive system of dealing with this presenting complaint (box 1). Box 1 Objectives of assessment of patients with chest pain c To undertake a primary survey of the patient and treat any immediately life threatening problems c To identify any patients who have a normal primary survey but have an obvious need for hospital admission c To undertake a secondary survey considering other systems of the body where dysfunction could present as chest pain c To consider a list of differential diagnoses c Discuss treatment based on the probable diagnosis(es) and whether home management or hospital admission is appropriate c Consider follow up if not admitted c PRIMARY SURVEY ABC principles Primary survey—If any of the following present treat immediately and transfer http://emj.bmj.com/ to hospital c Airway obstruction c Respiratory rate ,10 or .29 per minute c O2 sats ,93% c Pulse ,50 or .120 c Systolic BP ,90 mm Hg c Glasgow coma score ,12 on September 25, 2021 by guest.