The Farc-Ep and Revolutionary Social Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Colombian Peace Process Dag Nylander, Rita Sandberg

REPORT February 2018 Dag Nylander, Rita Sandberg and Idun Tvedt1 Designing peace: the Colombian peace process The peace talks between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP) have become a global reference for negotiated solutions to armed conflicts. The talks demonstrated how a well-prepared and robust process design can contrib- ute significantly to the outcome of a negotiated settlement. In several ways the pro- cess broke new ground. The parties developed frameworks and established mecha- nisms that laid the groundwork for building legitimacy for the process and increasing confidence in it. The direct participation of victims at the negotiating table and the effective inclusion of gender in the process are examples of this. Important elements of the process design included the into and out of Colombia; following:1 • gender inclusion by ensuring the participation of women and a gender focus in the peace agreement; • a secret initial phase to establish common ground; • broad and representative delegations; • a short and realistic agenda; • the extensive use of experts at the negotiating table • a limited objective: ending the conflict; and bilaterally with the parties; and • the principle that “incidents on the ground shall not • the implementation of confidence-building measures. interfere with the talks”; • the holding of talks outside Colombia to protect the process; Introduction • rules regulating the confidentiality of the talks; • the principle that “nothing is agreed until everything The peace talks between the Government of Colombia and is agreed”; the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s • a high frequency of negotiation meetings to ensure Army (FARC-EP) concluded with the signing of a peace continuity; agreement on November 24th 2016 after five years of ne- • direct talks with no formal mediator, but with third- gotiations. -

FARC During the Peace Process by Mark Wilson

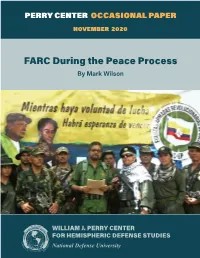

PERRY CENTER OCCASIONAL PAPER NOVEMBER 2020 FARC During the Peace Process By Mark Wilson WILLIAM J. PERRY CENTER FOR HEMISPHERIC DEFENSE STUDIES National Defense University Cover photo caption: FARC leaders Iván Márquez (center) along with Jesús Santrich (wearing sunglasses) announce in August 2019 that they are abandoning the 2016 Peace Accords with the Colombian government and taking up arms again with other dissident factions. Photo credit: Dialogo Magazine, YouTube, and AFP. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not an official policy nor position of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense nor the U.S. Government. About the author: Mark is a postgraduate candidate in the MSc Conflict Studies program at the London School of Economics. He is a former William J. Perry Center intern, and the current editor of the London Conflict Review. His research interests include illicit networks as well as insurgent conflict in Colombia specifically and South America more broadly. Editor-in-Chief: Pat Paterson Layout Design: Viviana Edwards FARC During the Peace Process By Mark Wilson WILLIAM J. PERRY CENTER FOR HEMISPHERIC DEFENSE STUDIES PERRY CENTER OCCASIONAL PAPER NOVEMBER 2020 FARC During the Peace Process By Mark Wilson Introduction The 2016 Colombian Peace Deal marked the end of FARC’s formal military campaign. As a part of the demobilization process, 13,000 former militants surrendered their arms and returned to civilian life either in reintegration camps or among the general public.1 The organization’s leadership were granted immunity from extradition for their conduct during the internal armed conflict and some took the five Senate seats and five House of Representatives seats guaranteed by the peace deal.2 As an organiza- tion, FARC announced its transformation into a political party, the Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Común (FARC). -

Sandra Carolina Ramos Torres

¡QUEREMOS HABLAR! ANÁLISIS DEL AGENCIAMIENTO POLÍTICO DE LAS EXCOMBATIENTES DE LAS FARC-EP DE COLINAS-GUAVIARE 1 Presenta: Sandra Carolina Ramos Torres Asesor de Tesis: Luis Fernando Bravo León Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas Maestría en Investigación Social Interdisciplinaria Línea Imaginarios y Representaciones Sociales Agosto 2018. 2 Dedico este trabajo con amor a mi madre por su perseverancia y ejemplo, a mi compañero de camino quien es mi cómplice de vida, a mi familia, a todas las mujeres excombatientes de las FARC-EP especialmente a las que ahora son madres y a todas las personas que contribuyen desde su quehacer a un mundo equitativo y justo. AGRADECIMIENTOS Este trabajo no se hubiese podido llevar a cabo sin las mujeres excombatientes de las FARC-EP del espacio territorial de capacitación y reincorporación la Jaime Pardo Leal Colinas Guaviare, Jaidy, Ingrid, Mayerly, Alejandra, Mary y especialmente a Sofía Nariño 3 por brindarme su sincera amistad, por ser guía durante éste proceso y a su familia que me ha acogido como un miembro más. A Oscar por sus aportes que hicieron posible este trabajo. Al maestro Luis Fernando Bravo León por motivarme a hacer ésta investigación y por orientarme de manera clara y oportuna. A la madre naturaleza por haberme permitido conocido a tan valerosas mujeres y por llenarme de aprendizajes en cada paso que doy. A mis amigas quienes también son fuente de inspiración, fortaleza y emancipación Mar, Nidya, Ángela y Yuly. RESUMEN La presente investigación se desarrolló con las mujeres excombatientes de las FARC-EP durante los años 2017 y 2018 del espacio territorial de capacitación y reincorporación Jaime Pardo Leal en Colinas Guaviare. -

Marisol Cano Busquets

Violencia contra los periodistas Configuración del fenómeno, metodologías y mecanismos de intervención de organizaciones internacionales de defensa de la libertad de expresión Marisol Cano Busquets TESIS DOCTORAL UPF / 2016 DIRECTORA DE LA TESIS Dra. Núria Almiron Roig DEPARTAMENTO DE COMUNICACIÓN A Juan Pablo Ferro Casas, con quien estamos cosidos a una misma estrella. A Alfonso Cano Isaza y María Antonieta Busquets Nel-lo, un árbol bien plantado y suelto frente al cielo. Agradecimientos A la doctora Núria Almiron, directora de esta tesis doctoral, por su acom- pañamiento con el consejo apropiado en el momento justo, la orientación oportuna y la claridad para despejar los caminos y encontrar los enfoques y las perspectivas. Además, por su manera de ver la vida, su acogida sin- cera y afectuosa y su apoyo en los momentos difíciles. A Carlos Eduardo Cortés, amigo entrañable y compañero de aventuras intelectuales en el campo de la comunicación desde nuestros primeros años en las aulas universitarias. Sus aportes en la lectura de borradores y en la interlocución inteligente sobre mis propuestas de enfoque para este trabajo siempre contribuyeron a darle consistencia. A Camilo Tamayo, interlocutor valioso, por la riqueza de los diálogos que sostuvimos, ya que fueron pautas para dar solidez al diseño y la estrategia de análisis de la información. A Frank La Rue, exrelator de libertad de expresión de Naciones Unidas, y a Catalina Botero, exrelatora de libertad de expresión de la Organización de Estados Americanos, por las largas y fructíferas conversaciones que tuvimos sobre la situación de los periodistas en el mundo. A los integrantes de las organizaciones de libertad de expresión estudia- das en este trabajo, por haber aceptado compartir conmigo su experien- cia y sus conocimientos en las entrevistas realizadas. -

Justice for Colombia Peace Monitor REPORT #02 WINTER 2018/2019

Justice for Colombia Peace Monitor REPORT #02 WINTER 2018/2019 1 Justice for Colombia Peace Monitor REPORT #02 WINTER 2018/2019 A Justice for Colombia project Supported by Fórsa 2 Index Section 1 Section 4 1 Introduction 5 6 Main Advances of Implementation 14 I Renewed Executive Support for Peace Process 14 2 Recommendations 6 II Renovation of Implementation Institutions 14 III Initiation of Special Jurisdiction for Peace 15 Section 2 IV FARC Political Participation 15 3 Background 7 V Established Advances – End of Armed Conflict 15 and tripartite Collaboration I What is the Justice for Colombia Peace Monitor? 7 II What is Justice for Colombia? 7 7 Main Concerns of Implementation 16 I Challenges to the Special Jurisdiction for Peace 16 4 Details of Delegation 8 II Funding for Implementation 17 I Members of the Delegation 8 III Jesús Santrich and Legal Security for FARC Members 17 II Meetings 10 IV Comprehensive Rural Reform 18 III Locations 11 V Crop Substitution 19 VI Socioeconomic Reincorporation 20 Section 3 VII Killing of FARC Members 20 5 Introduction to the Colombian Peace Process 12 VIII Murder of Social Leaders and Human Rights Defenders 21 I Timeline of Peace Process 12 CASE STUDY: Peasant Association of Catatumbo (ASCAMCAT) 22 II Summary of the Final Agreement 13 Section 5 8 Conclusions 23 Section 1 1. Introduction This report details the conclusions from the Justice for Justice for Colombia, and the JFC Peace Monitor and Colombia (JFC) Peace Monitor delegation to Colom- all its supporters are grateful to all of the individuals, bia which took place between 15 and 21 August 2018. -

Ending Colombia's FARC Conflict: Dealing the Right Card

ENDING COLOMBIA’S FARC CONFLICT: DEALING THE RIGHT CARD Latin America Report N°30 – 26 March 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. FARC STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES................................................................... 2 A. ADAPTIVE CAPACITY ...................................................................................................................4 B. AN ORGANISATION UNDER STRESS ..............................................................................................5 1. Strategy and tactics ......................................................................................................................5 2. Combatant strength and firepower...............................................................................................7 3. Politics, recruitment, indoctrination.............................................................................................8 4. Withdrawal and survival ..............................................................................................................9 5. Urban warfare ............................................................................................................................11 6. War economy .............................................................................................................................12 -

Ending Colombia's FARC Conflict

ENDING COLOMBIA’S FARC CONFLICT: DEALING THE RIGHT CARD Latin America Report N°30 – 26 March 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. FARC STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES................................................................... 2 A. ADAPTIVE CAPACITY ...................................................................................................................4 B. AN ORGANISATION UNDER STRESS ..............................................................................................5 1. Strategy and tactics ......................................................................................................................5 2. Combatant strength and firepower...............................................................................................7 3. Politics, recruitment, indoctrination.............................................................................................8 4. Withdrawal and survival ..............................................................................................................9 5. Urban warfare ............................................................................................................................11 6. War economy .............................................................................................................................12 -

Facultad De Comunicación Social

UNIVERSIDAD CENTRAL DEL ECUADOR FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL LA GUERRA MEDIÁTICA DE BAJA INTENSIDAD DE LA OLIGARQUÍA COLOMBIANA Y EL IMPERIALISMO YANQUI CONTRA LAS FARC-EP TESIS PREVIA A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADA EN COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL VILLACÍS TIPÁN GABRIELA ALEXANDRA DIRECTOR SOC. CÉSAR ALFARO, ALBORNOZ JAIME Quito – Ecuador 2013 DEDICATORIA A la guerrillerada fariana, heroínas y héroes de la Colombia insurgente de Bolívar. A la memoria de Manuel Marulanda, Raúl Reyes, Martín Caballero, Negro Acacio, Iván Ríos, Mariana Páez, Lucero Palmera, Jorge Briceño, Alfonso Cano, Carlos Patiño y de todas y todos los guerrilleros de las FARC-EP que han ofrendando su vida por la construcción de la Nueva Colombia. ¡Los que mueren por la vida, no pueden llamarse muertos! A la Delegación de Paz de las FARC-EP que en La Habana-Cuba lucha por alcanzar la paz con justicia social para Colombia. A Iván Márquez y Jesús Santrich, hermanos revolucionarios. ii AUTORIZACIÓN DE LA AUTORÍA INTELECTUAL Yo, Gabriela Alexandra Villacís Tipán en calidad de autor del trabajo de investigación o tesis realizada sobre “La guerra mediática de baja intensidad de la oligarquía colombiana y el imperialismo yanqui contra las FARC-EP”, por la presente autorizo a la UNIVERSIDAD CENTRAL DEL ECUADOR, hacer uso de todos los contenidos que me pertenecen o parte de los que contiene la obra, con fines estrictamente académicos o de investigación. Los derechos que como autor me corresponden, con excepción de la presente autorización, seguirán vigentes a mi favor, de conformidad con lo establecido en los artículos 5, 6, 8, 19 y demás pertinentes de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual y su reglamento. -

Corte Suprema De Justicia

República de Colombia Corte Suprema de Justicia CORTE SUPREMA DE JUSTICIA SALA DE CASACIÓN PENAL LUIS ANTONIO HERNÁNDEZ BARBOSA Magistrado Ponente SP5831-2016 Radicación 46061 Aprobado Acta No. 141 Bogotá D.C., cuatro (4) de mayo de dos mil dieciséis (2016). VISTOS: La Corte resuelve los recursos de apelación interpuestos contra la sentencia parcial proferida por la Sala de Justicia y Paz del Tribunal Superior de Medellín el 2 de febrero de 2015, respecto del postulado RAMIRO VANOY MURILLO, comandante del Bloque Mineros de las AUC. 1 SEGUNDA INSTANCIA JUSTICIA Y PAZ 46061 RAMIRO VANOY MURILLO ANTECEDENTES FÁCTICOS: Con el propósito de facilitar el cabal entendimiento de las conductas objeto de juzgamiento en este proceso, su gravedad e incidencia en las comunidades afectadas por ellas, antes de adoptar la decisión correspondiente, la Corte estima indispensable referirse al marco histórico en el cual tuvieron desarrollo. Para ello recurrirá a lo establecido, de manera general por la Sala en anteriores oportunidades sobre la génesis y desarrollo de los denominados grupos paramilitares1. En lo particular, es decir en lo atinente al Bloque Mineros, se apoyará en lo consignado por el Tribunal de instancia en el fallo recurrido, con fundamento en la actuación donde se origina. Inicio de las autodefensas Si bien el fenómeno de violencia en Colombia es bastante anterior, diferentes estudios sobre la evolución del paramilitarismo2, coinciden en ubicar como punto de 1 Cfr. Sentencia del 27/04/11 Rad. 34547. 2 Cfr. Giraldo Moreno, Javier, S.J., El paramilitarismo: una criminal política de Estado que devora el país, agosto de 2004, www.javiergiraldo.org. -

Final Agreement for Ending the Conflict and Building a Stable and Lasting Peace

United Nations S/2017/272 Security Council Distr.: General 21 April 2017 Original: English Letter dated 29 March 2017 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council In accordance with the Final Agreement for Ending the Conflict and Building a Stable and Lasting Peace, signed on 24 November 2016, between the Government of Colombia and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP), on 24 March 2017, I received a signed original of the Final Agreement from the Permanent Representative of Colombia to the United Nations, María Emma Mejía Vélez, along with a letter from the President of the Republic of Colombia, Juan Manuel Santos Calderón. I welcome this historic achievement, and have the honour to transmit herewith the letter (see annex I) and the Final Agreement (see annex II). I should be grateful if you could circulate both documents to the members of the Security Council. (Signed) António Guterres 17-06469 (E) 300617 070717 *1706469* S/2017/272 Annex I I would like to reiterate my best wishes to you in your new post as Secretary- General of the United Nations. The United Nations is playing a decisive role in the consolidation of peace in Colombia, and our permanent dialogue and exchange of views will be very important in this process. I would also like to officially express the Colombian Government’s good faith through a unilateral State declaration, and herewith submit the full text of the Final Agreement for Ending the Conflict and Building a Stable and Lasting Peace in Colombia, which was signed by the national Government and by the Revolutionary Armed Forces — People’s Army (FARC-EP) on 24 November 2016 in Bogotá. -

El Intelectual Orgánico En Las FARC EP En El Período Comprendido Entre 2000 a 2011, Un Estudio De Caso De: Alfonso Cano Paola

1 El intelectual orgánico en las FARC EP en el período comprendido entre 2000 a 2011, un estudio de caso de: Alfonso Cano Paola Patricia Sandoval Palacios Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Ciencias Económicas Bogotá, Colombia 2020 2 El intelectual orgánico en las FARC EP en el período comprendido entre 2000 a 2011, un estudio de caso de: Alfonso Cano Paola Patricia Sandoval Palacios Tesis o trabajo de investigación presentada(o) como requisito parcial para optar al título de: Magister en Estudios Políticos y Relaciones Internacionales Director (a): José Francisco Puello-Socarrás Línea de Investigación: Cultura Política Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Ciencias Económicas Bogotá, Colombia 2020 3 Resumen La presente investigación analiza la trayectoria de la producción intelectual de Alfonso Cano buscando examinar su incidencia política, en tanto intelectual orgánico, dentro de la vida política de las FARC-EP entre 2000 y 2011. Así, se pretende determinar la relevancia que ha tenido la relación que se configura y consolida entre los intelectuales orgánicos y la insurgencia en la que militan, en este caso a partir de un estudio de caso de uno de los sujetos más importantes de esta guerrilla colombiana. A partir de un análisis de contenido e ideacional se busca examinar la producción intelectual del comandante guerrillero para definir la articulación de las propuestas elaboradas, las cuales se trabajan desde los ejes programáticos, estratégicos y organizativos para las FARC- EP, y se analizan a la luz de las dinámicas internas de esta guerrilla. Finalmente, se evidencia una relación entre la producción intelectual de Alfonso Cano y su incidencia en la vida política de las FARC-EP. -

The Hope for Peace in Colombia Pedro Valenzuela

armed conflict and peace processes 47 II. Out of the darkness? The hope for peace in Colombia pedro valenzuela On 24 November 2016, after more than five decades of armed conflict, several failed peace processes and four years of negotiations, the Colombian Gov- ernment and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People’s Army (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo, FARC– EP) signed the Final Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace (the Accord).1 The Accord ended a conflict that has cost the lives of around 220 000 people, led to the disappearance of 60 000 more, forcibly recruited 6000 minors and left 27 000 victims of kidnapping as well as more than 6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees.2 This section discusses the circumstances that made the Accord possible, the development of the process and the challenges that lie ahead. Factors leading to negotiations The origins of FARC can be traced to the peasant self-defence units created by the Communist Party during the inter-party conflicts of the 1940s and 1950s, known to Colombians simply as ‘The Violence’. After its formal cre- ation in 1966 and throughout the 1970s, when the armed conflict was fairly marginal, FARC was closely allied with the Communist Party of Colombia. In the 1980s, however, it distanced itself from the Communist Party and promoted clandestine political structures, while attempting to expand into every province of the country, gain power at the local level, bring the war closer to the