Institutions of Collective Action and Smallholder Performance: Evidence from Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

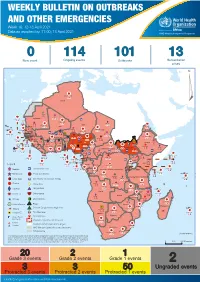

Week 16: 12-18 April 2021

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 16: 12-18 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 18 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 114 101 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 119 642 3 155 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 694 170 Mauritania 7 2 13 070 433 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 129 453 Mali 3 491 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 706 169 Eritrea Cape Verde 39 782 1 091 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 20 466 191 973 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 242 028 3 370 0 164 233 2 061 Guinea 13 129 154 12 38 397 1 3 712 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 61 731 919 52 14 Ghana 5 787 75 Côte d'Ivoire 10 473 114 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 97 17 25 0 21 612 260 45 560 274 91 709 771 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 151 653 2 481 655 2 43 0 119 12 6 1 488 6 4 028 79 12 533 7 259 106 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 378 338 Kenya Legend 7 611 95 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 275 35 23 888 325 Measles 21 858 133 Democratic Republic of the Congo 10 084 137 Burundi 3 612 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 28 956 745 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 190 0 4875 25 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 24 389 561 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 90 918 1 235 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 941 1 138 862 0 3 815 146 Zambia 133 0 Mozambique -

Livelihood Zone Descriptions

Government of Senegal COMPREHENSIVE FOOD SECURITY AND VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS (CFSVA) Livelihood Zone Descriptions WFP/FAO/SE-CNSA/CSE/FEWS NET Introduction The WFP, FAO, CSE (Centre de Suivi Ecologique), SE/CNSA (Commissariat National à la Sécurité Alimentaire) and FEWS NET conducted a zoning exercise with the goal of defining zones with fairly homogenous livelihoods in order to better monitor vulnerability and early warning indicators. This exercise led to the development of a Livelihood Zone Map, showing zones within which people share broadly the same pattern of livelihood and means of subsistence. These zones are characterized by the following three factors, which influence household food consumption and are integral to analyzing vulnerability: 1) Geography – natural (topography, altitude, soil, climate, vegetation, waterways, etc.) and infrastructure (roads, railroads, telecommunications, etc.) 2) Production – agricultural, agro-pastoral, pastoral, and cash crop systems, based on local labor, hunter-gatherers, etc. 3) Market access/trade – ability to trade, sell goods and services, and find employment. Key factors include demand, the effectiveness of marketing systems, and the existence of basic infrastructure. Methodology The zoning exercise consisted of three important steps: 1) Document review and compilation of secondary data to constitute a working base and triangulate information 2) Consultations with national-level contacts to draft initial livelihood zone maps and descriptions 3) Consultations with contacts during workshops in each region to revise maps and descriptions. 1. Consolidating secondary data Work with national- and regional-level contacts was facilitated by a document review and compilation of secondary data on aspects of topography, production systems/land use, land and vegetation, and population density. -

Les Resultats Aux Examens

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar OFFICE DU BACCALAUREAT B.P. 5005 - Dakar-Fann – Sénégal Tél. : (221) 338593660 - (221) 338249592 - (221) 338246581 - Fax (221) 338646739 Serveur vocal : 886281212 RESULTATS DU BACCALAUREAT SESSION 2017 Janvier 2018 Babou DIAHAM Directeur de l’Office du Baccalauréat 1 REMERCIEMENTS Le baccalauréat constitue un maillon important du système éducatif et un enjeu capital pour les candidats. Il doit faire l’objet d’une réflexion soutenue en vue d’améliorer constamment son organisation. Ainsi, dans le souci de mettre à la disposition du monde de l’Education des outils d’évaluation, l’Office du Baccalauréat a réalisé ce fascicule. Ce fascicule représente le dix-septième du genre. Certaines rubriques sont toujours enrichies avec des statistiques par type de série et par secteur et sous - secteur. De même pour mieux coller à la carte universitaire, les résultats sont présentés en cinq zones. Le fascicule n’est certes pas exhaustif mais les utilisateurs y puiseront sans nul doute des informations utiles à leur recherche. Le Classement des établissements est destiné à satisfaire une demande notamment celle de parents d'élèves. Nous tenons à témoigner notre sincère gratitude aux autorités ministérielles, rectorales, académiques et à l’ensemble des acteurs qui ont contribué à la réussite de cette session du Baccalauréat. Vos critiques et suggestions sont toujours les bienvenues et nous aident -

Figure 4.1 Map of Dakar, Senegal...29

Public Disclosure Authorized Baseline and feasibility assessment for alternative cooking fuels in Senegal Public Disclosure Authorized May 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized © 2014 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, MSN U11-1102 Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-458-7955 Fax: 202-522-2654 Website: http:// www.worldbank.org All rights reserved The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. Baseline and feasibility assessment for alternative cooking fuels in Senegal 2 Contents Acronyms and abbreviations ............................................................................................. 6 Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................. -

SENEGAL Last Updated: 2007-05-22

Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System (VMNIS) WHO Global Database on Iodine Deficiency The database on iodine deficiency includes data by country on goitre prevalence and/or urinary iodine concentration SENEGAL Last Updated: 2007-05-22 Goitre Urinary iodine (µg/L) Notes prevalence (%) Distribution (%) Prevalence (%) Age Sample Grade Grade TGP <20 20-49 50-99100-299 >300 <100 Median Mean SD Reference General Line Level Date Region and sample descriptor Sex (years) size 1 2 D 2003 Véligara department: SAC by area: Urban B 6.00 - 12.99 65 53.8 12.7 5128 * Véligara department: SAC by area: Rural B 6.00 - 12.99 84 40.5 25.4 Vélingara department: SAC by area: Urban B 6.00 - 12.99 677 2.2 * Vélingara department: SAC by area: Rural B 6.00 - 12.99 878 1.2 Vélingara department: Women by area: Urban F NS 358 5.3 Vélingara department: Women by area: Rural F NS 306 4.2 Vélingara department: PW by area: Urban F NS 46 13.0 Vélingara department: PW by area: Rural F NS 61 11.5 L 1999P Casamance area: 6 villages: All B 5.00 - 60.99 109 97.0 20.0 1563 * 1 Casamance area: 6 villages: All B 5.00 - 60.99 160 30.0 10.6 40.6 * L 1997 Bambey, Kebemer and Koungheul: SAC B 6.00 - 12.99 400 15.0 28.0 38.0 81.0 5129 * S 1995 -1997 Tambacounda and Casamance regions: All: Total B 10.00 - 50.99 8797 21.5 24.5 18.3 64.4 5282 * Tambacounda and Casamance regions: PW F NS 462 50.0 All by region: Tambacounda urban B 10.00 - 50.99 866 17.7 25.1 24.2 67.0 61.1 All by region: Tambacounda rural B 10.00 - 50.99 793 43.6 37.2 12.8 93.6 23.0 All by department: Bakel B -

Bayesian Spatial Models Applied to Malaria Epidemiology

Bayesian spatial models applied to malaria epidemiology INAUGURALDISSERTATION zur Erlangung der W¨urdeeines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at der Universit¨atBasel von Federica Giardina aus Pescara, Italien Basel, December 2015 Original document stored on the publication server of the University of Basel edoc.unibas.ch Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨atauf Antrag von Prof. Dr. M. Tanner, P.D. Dr. P. Vounatsou, and Prof. Dr. A. Biggeri. Basel, den 10 December 2013 Prof. Dr. J¨orgSchibler Dekan Science is built up with facts, as a house is with stones. But a collection of facts is no more a science than a heap of stones is a house. (Henri Poincar´e) iv Summary Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease caused by parasitic protozoans of the genus Plasmodium and transmitted to humans via the bites of infected female Anopheles mos- quitoes. Although progress has been seen in the last decade in the fight against the disease, malaria remains one of the major cause of morbidity and mortality in large areas of the developing world, especially sub-Saharan Africa. The main victims are children under five years of age. The observed reductions are going hand in hand with impressive increases in international funding for malaria prevention, control, and elimination, which have led to tremendous expansion in implementing national malaria control programs (NMCPs). Common interventions include indoor residual spraying (IRS), the use of insecticide treated nets (ITN) and environmental measures such as larval control. Specific targets have been set during the last decade. The Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 6 aims to halve malaria incidence by 2015 as compared to 1990 and to achieve universal ITN coverage and treatment with appropriate antimalarial drugs. -

Indigenous Knowledge

Indigenous Knowledge Local Pathways to Global Development Marking Five Years of the World Bank Indigenous Knowledge for Development Program i © 2004 Knowledge and Learning Group Africa Region The World Bank IK Notes reports periodically on indigenous knowledge (IK) initiatives in Sub-Saharan Africa and occasionally on such initiatives outside the Region. It is published by the Africa Region’s Knowledge and Learning Group as part of an evolving IK partnership between the World Bank, communities, NGOs, development institutions, and multilateral organizations. For information, please e-mail: [email protected]. The Indigenous Knowledge for Development Program can be found on the web at http://worldbank.org/afr/ik/default.htm The views and opinions expressed within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the World Bank or any of its affiliated organizations. iii Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................ vii Preface ................................................................................................................................................................................ ix Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................................................ x Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................. -

SÉNÉGAL Rapport Spécial

SENEGAL Special Report August 31, 2015 Poor start to the agropastoral season in central and northern areas KEY MESSAGES This year, farmers are resorting to short-cycle varieties of cowpea and Souna millet crops more than usual as a strategy to limit the negative effects of the late start of the rains on crop production in order to ensure near-average crop yields. With the likely downsizing of the land area planted in groundnuts, Senegal’s main cash crop, household incomes between December and March will likely be below average. The poor pastoral conditions between February and June severely affected pastoral incomes, which have been well below-average as a result of the decline in animal production and livestock prices. The larger than usual numbers of animal deaths have adversely affected the livelihoods of pastoral households, limiting their food access on local markets. However, the recent recovery of pastures and replenishment of watering holes have helped improve the situation in many pastoral areas. Food assistance from the government and its humanitarian partners is easing poor households’ food insecurity. Humanitarian food and non-food assistance and cash transfer programs will limit the use of atypical coping strategies (ex. borrowing and reducing food and nonfood expenditures) by recipient households. An examination of food prices on domestic markets shows prices for locally grown millet still slightly above-average and prices for regular broken rice, the main foodstuff consumed by Senegalese households, at below-average levels. However, despite these prices, the below-average incomes of poor agropastoral households is preventing many households from adequating accessing these food items. -

Comportements En Matière D'hygiène Et D'assainissement Et Volonté De Payer En Milieu Rural Au Sénégal

Swiss TPH | Enquête hygiene et assainissement, Sénégal – Rapport final – Version finale_18.11.2015 Swiss Centre for International Health Programme Eau et Assainissement, Banque Mondiale Enquête ménage: comportements en matière d'hygiène et d'assainissement et volonté de payer en milieu rural au Sénégal Appui à la Direction de l'Assainissement Rapport final Swiss TPH ISED Consultants Lise Beck Mayassine Diongue Sylvain Faye Peter Steinmann Cheikh Fall Tidiane Ndoye Ibrahima Sy Adama Faye Alioune Touré Martin Bratschi Anta Tal Dia Kaspar Wyss Basel, 18 novembre 2015 Page 1 / 136 Swiss TPH | Enquête hygiene et assainissement, Sénégal – Rapport final – Version finale_18.11.2015 Contacts Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute Institut de Santé et Développement Socinstrasse 57 Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar (UCAD) P.O. Box BP 16390 4002 Basel Dakar-Fann Switzerland Sénégal Kaspar Wyss Anta Tal Dia Head of Systems Support Unit Director ISED Swiss Centre for International Health (SCIH) Tel: +221 33 824 98 78 T: +41 61 284 81 40 Fax: +221 33 825 36 48 F: +41 61 284 81 03 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.scih.ch / www.swisstph.ch Website: http://www.ised.sn/ Financement Cette étude est menée pour le compte du Programme Eau et Assainissement (PEA), qui fait partie d’un partenariat de plusieurs donneurs administré par le Groupe de la Banque Mondiale. Le but est d’appuyer les populations pauvres dans l’accès à des services en eau et en assainissement qui sont abordables, sûrs et durables. Avertissement Les idées et opinions exprimées dans ce document sont ceux des auteurs et n’impliquent pas ou ne reflètent pas nécessairement les opinions de l’Institut. -

Mapping and Remote Sensing of the Resources of the Republic of Senegal

MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING OF THE RESOURCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL A STUDY OF THE GEOLOGY, HYDROLOGY, SOILS, VEGETATION AND LAND USE POTENTIAL SDSU-RSI-86-O 1 -Al DIRECTION DE __ Agency for International REMOTE SENSING INSTITUTE L'AMENAGEMENT Development DU TERRITOIRE ..i..... MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING OF THE RESOURCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL A STUDY OF THE GEOLOGY, HYDROLOGY, SOILS, VEGETATION AND LAND USE POTENTIAL For THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL LE MINISTERE DE L'INTERIEUP SECRETARIAT D'ETAT A LA DECENTRALISATION Prepared by THE REMOTE SENSING INSTITUTE SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY BROOKINGS, SOUTH DAKOTA 57007, USA Project Director - Victor I. Myers Chief of Party - Andrew S. Stancioff Authors Geology and Hydrology - Andrew Stancioff Soils/Land Capability - Marc Staljanssens Vegetation/Land Use - Gray Tappan Under Contract To THE UNITED STATED AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING PROJECT CONTRACT N0 -AID/afr-685-0233-C-00-2013-00 Cover Photographs Top Left: A pasture among baobabs on the Bargny Plateau. Top Right: Rice fields and swamp priairesof Basse Casamance. Bottom Left: A portion of a Landsat image of Basse Casamance taken on February 21, 1973 (dry season). Bottom Right: A low altitude, oblique aerial photograph of a series of niayes northeast of Fas Boye. Altitude: 700 m; Date: April 27, 1984. PREFACE Science's only hope of escaping a Tower of Babel calamity is the preparationfrom time to time of works which sumarize and which popularize the endless series of disconnected technical contributions. Carl L. Hubbs 1935 This report contains the results of a 1982-1985 survey of the resources of Senegal for the National Plan for Land Use and Development. -

LEÏDI LABORATORY "Territorial Dynamics and Development

GASTON BERGER UNIVERSITY LEÏDI LABORATORY "Territorial Dynamics and Development REPORT OF THE RESEARCH COMMITTEE FOR THE REALIZATION OF AN INVENTORY OF DATA AND TOOLS IN THE CADASTRAL SECTOR IN SENEGAL Presented by Mouhamadou Mawloud DIAKHATÉ Full Professor of Universities Laboratory Director October, 2020 CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS INTRODUCTION I/ HISTORY OF THE EVOLUTION OF THE ORGANIZATION OF STATE STRUCTURES II/ INVENTORY OF STAKEHOLDERS AND EXISTING DATA III/ RESPONSIBILITIES AND COMMITMENT OF THE ACTORS IN THE COLLECTION OF CADASTRAL DATA IV/ RELIABLE CADASTRAL DATA AND MONITORING OF ODDS V/ ROADMAP FOR STRENGTHENING THE CADASTRAL ECOSYSTEM V.1 Objectives of strengthening the cadastral ecosystem V.2 Contribution of spatial remote sensing and geographic information systems (GIS) and statistics to the modernization of the national cadastre V.2.1. Implementation of a multi-purpose cadastre in Senegal V.2.2. Thematic maps V.2.3. 2D and 3D Carto. V.2.4. Statistical modelling V.2.5. Methodology for the elaboration of the comic book V.3 Content of the roadmap V.4. Priority and Roadmap Agenda CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY ITEMS 2 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ANDS : National Agency of Statistics and Demography ArcGIS: Suite of geographic information software developed by Esri ADB: African Development Bank BAGDOC: Office of General Affairs and Documentation BD TOPO: Topographic data bank BLC: Office of Legislation and Litigation PRB: Public Relations Office CAGF: Framework for analysis of land governance CGE: Center for Large Enterprises -

A Hrc Wg.6 31 Sen 1 E.Pdf

United Nations A/HRC/WG.6/31/SEN/1 General Assembly Distr.: General 31 August 2018 English Original: French Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Thirty-first session 5–16 November 2018 National report submitted in accordance with paragraph 5 of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 16/21* Senegal I. Introduction and methodology for preparation of the report 1. This report is submitted in follow-up to the presentation of the second report of Senegal to the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review at its seventeenth session in 2013. It reflects the efforts to implement the recommendations that Senegal had accepted. 2. With technical and financial support from the Regional Office for West Africa of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, based in Dakar, the Ministry of Justice, through the National Advisory Council on Human Rights, led the process of preparing the report. The National Advisory Council on Human Rights is a standing government body, made up of representatives of all ministerial departments, of a large number of the most representative civil society organizations, and also of the national human rights institution — the Senegalese Human Rights Committee — and of Parliament. 3. A national action plan for the period 2016–2018 was drafted by a technical committee composed of focal points from key ministries, appointed by the National Advisory Council on Human Rights. The draft report was drawn up on the basis of the information that had been gathered and was then considered at a dissemination and validation workshop with the participation of national institutions and civil society.