Transit Revitalization Investment Districts Opportunities and Challenges for Implementation Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railroad Postcards Collection 1995.229

Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Railroad stations .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Alabama ................................................................................................................................................... -

RFP) Wilkinsburg Transit Revitalization Investment District (TRID) Planning Study

REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (RFP) Wilkinsburg Transit Revitalization Investment District (TRID) Planning Study RFP Issue Date: June 15, 2017 Proposals Due Date: July 21, 2017 at 4 PM ET Section 1. General Information: 1.1 The Borough of Wilkinsburg requests proposals from transportation, economic development and urban planning consultants to author a planning study that identifies transit-oriented development and infrastructure opportunities in and near the Borough of Wilkinsburg within the vicinity of Allegheny County’s Martin Luther King, Jr. East Busway and examines the feasibility of creating a TRID district in the study area. 1.2 The project budget is $75,000. The project duration is estimated to be 12 months. Interested parties are requested to submit a detailed Proposal Package that clearly defines the relevant experience of the proposed staff and subconsultant team members, as well as proposed methods and strategy to carry out the project scope of work. 1.3 Contact person for all queries and for receipt of proposals: Donn Henderson Borough Manager Borough of Wilkinsburg 605 Ross Ave Wilkinsburg, PA 15221 1 | Page 412-244-2906 [email protected] 1.4 Respondents shall restrict all contact and questions regarding this RFP and selection process to the individual named herein. Questions concerning terms, conditions and technical specifications shall be directed in writing to Donn Henderson (See section 1.3). Questions will be answered in writing on the Borough of Wilkinsburg website under the rfp by June 30, 2017 (http://www.wilkinsburgpa.gov). Questions submitted after June 27, 2017 will not be answered. 1.5 Consideration is expected to be given, but is not guaranteed to be given, to the criteria listed in this RFP. -

Power District Development RFQ 2016-072

Submitted by: Cross Street Partners 2400 Boston Street Suite 404 Baltimore, MD 21224 Urban Design Associates 3 PPG Place 3rd Floor W Pittsburgh, PA 15222 Request for Qualifications: Power District Development RFQ 2016-072 June 9, 2016 Table of Contents Section 1: Cover Letter 5 Section 2: Developer and Team Qualifications 7 Section 3: Conceptual Approach 55 CROSS STREET City of Gainesville - Power District Development Table of Contents | 3 PARTNERS CROSS STREET City of Gainesville - Power District Development Cover Letter | 5 1PARTNERS Firm Name Cross Street Partners 2400 Boston Street, Suite 404 Baltimore, MD 21224 443.573.4066 office 443.573 4422 fax CrossStPartners.com Urban Design Associates 3 PPG Place, 3rd Floor Pittsburgh, PA 15222 412.263.5200 - office 844.270.8374 - fax UrbanDesignAssociates.com CROSS STREET City of Gainesville - Power District Development Developer and Team Qualifications | 7 2PARTNERS Ownership Structure Parent Company Cross Street Partners LLC (Developer) n/a Members: 2009 Nancy S. Struever Irrevocable Trust FBO Carl W. Struever and Descendents 46.61150% Stephen Hulse 17.79617% Joshua Parker 17.79617% Joseph Summers 17.79617% 100.0000% SHPS Investors LLC Members: 2009 Nancy S. Struever Irrevocable Trust FBO Carl W. Struever and Descendents 58.30550% Stephen Hulse 12.23150% Joshua Parker 12.23150% Joseph Summers 12.23150% Carl W. Struever 5.00000% 100.00000% CROSS STREET City of Gainesville - Power District Development Developer and Team Qualifications | 9 PARTNERS Officers and Principals Organization Chart -

The Martin Luther King, Jr. East Busway in Pittsburgh, PA

UMTA-PA-06-0081-87-1 " DU I The Martin Luther King, Jr. I'BC- Department East Busway in Pittsburgh ansportation wroan Mass :v- I Transportation UMTA/TSC Evaluation Series Final Report Administration October 1987 i\i' UMTA Technical Assistance Program NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the object of this report. - ,A57 Technical Report Documentation Page i>crr-^ 2 Government Accession Recipient's Catalog 1 . Report No. No 3 No. UMTA-PA-06-0081-87-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5 Report Date The Martin Luther King, Jr. October 1987 East Busway in Pittsburgh, PA, 6 Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) DTS-49 Susan, PultZ) and David Koffman Performing Organization Report No DOT-TSC-UMTA-87-6 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No (TRAIS) Crain & Associates, Inc.* UR701/U7201 120 Santa Margarita Avenue Menlo Park, CA 94025 D Contract or Grant No DOT-TSC-1755 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address — Type of Report and Period Covered U.S. Department of Transportation Final Report Urban Mass Transportation Administration February 1983 - November 1984 Office of Technical Assistance 14 Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590 URT-30 15 Supplementary Notes U.S. Department of Transportation and Special Programs Administration *Under contract to Research Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, MA 02142 16 Abstract The Port Authority of Allegheny County (PAT) , the primary public transit operator in Pittsburgh, PA, built an exclusive roadway for buses which opened for service in February 1983. -

East Liberty's Green Vision

East Liberty’s Green Vision Funding provided by: The Heinz Endowments PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Roy A. Hunt Foundation Executive Summary Advisory Committee Consultant Team John Schombert 3 Rivers Wet Weather Inc. Perkins Eastman Janie French 3 Rivers Wet Weather Inc. Stefani Danes, AIA LEED AP Marijke Hecht Western Pennsylvania Conservancy TreeVitalize Thomas Bartnik, AICP LEED AP Jeff Bergman 9 Mile Run Watershed Association Roland Baer, AIA Scott Bricker Bike Pittsburgh Arch Pelley, AIA Jeb Feldman City of Braddock Ann Gerace Conservation Consultants, Inc. Lauren Merski Jack Machek PA Department of Community Economic Development Melissa Annet Ellen Kight Pittsburgh Partnership for Neighborhood Development Sammy Van den Heuvel Monica Hoffman PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Patrice Fowler-Searcy East Liberty Presbyterian Church Cahill Associates Danielle Crumrine Tree Pittsburgh Thomas Cahill Matthew Erb Tree Pittsburgh Courtney Marm Eamon Geary Green Building Alliance Rebecca Flora Green Building Alliance Viridian Landscape Studio Caren Glotfelty The Heinz Endowments Tavis Dockwiller Janice Seigle Highmark Rolf Sauer Malik Bankston Kingsley Association Pat Buddemeyer Mellon’s Orchard Neighborhood Association Suzanna Fabry Gary Cirrincione Negley Place Neighborhood Alliance Robbie Ali Pitt Center for Healthy Environments and Communities ETM Associates David Jahn Pittsburgh City Forestry Division Timothy Marshall Noor Ismael Pittsburgh City Planning Dan Sentz Pittsburgh City Planning Pat Hassett -

Homewood Station Transit Oriented Development Study

HOMEWOOD STATION TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT STUDY Delta Development Group Studio for Spatial Practice Fourth Economy Consulting Cosmos Technologies Mongalo-Winston Consulting HOMEWOOD STATION TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT STUDY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Client Advisory Committee The Urban Redevelopment Authority Matt Barron Blyden O’Terry of Pittsburgh (URA) is the City of Office of the Mayor Point Breeze North Development Corporation Pittsburgh’s economic development Jamil Bay agency. Our goals are to create jobs, Consultant for Pittsburgh Community Justin Pizzella increase the city’s tax base, and Reinvestment Group East End Food Co-op improve the vitality of businesses, neighborhoods, and the City’s livability Marita Bradley Dennis Puko as a whole. Councilman Burgess’ Office Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Haesha Cooper Incorporated in 1946, the URA was one Development of the first redevelopment authorities Urban Innovation 21 Henry Pyatt in Pennsylvania. Organized by Melvin El Office of the Mayor, City of Pittsburgh corporate and civic leaders, the URA Representative Gainey’s Office undertook the first privately-financed Patrick Roberts Marteen Garay downtown redevelopment project in Department of City Planning the United States -- Gateway Center. Urban Innovation 21 & Homewood- Since then, the URA has constructed Brushton Business Association Chris Sandvig Pittsburgh Community Reinvestment and rehabilitated tens of thousands Elwin Green Group of homes, reclaimed thousands of Race Street Block Club acres of contaminated brownfield and Rebecca Schenck Seth Hufford riverfront sites, and assisted hundreds Urban Redevelopment Authority of Point Breeze North Development of businesses in neighborhoods Pittsburgh Corporation throughout the City of Pittsburgh. Michael Smith Jerome Jackson Today, the URA offers a variety of Pittsburgh Department of City Planning Operation Better Block programs and financing products Dianne B. -

Pittsburgh's East

Pittsburgh’s East End – A Legacy of Innovation By Mark Vernalis | FocusCFO Dear ACE Hotel: I am looking forward to my first ACE hotel visit tonight and dining at Whitfield. Not long ago I read in The Architect’s Newspaper (archpaper.com) that you would be coming to Pittsburgh. The archpaper.com writer expected to see Edison bulbs in the Pittsburgh ACE, which got me thinking about the neighborhood you will be joining and motivated me to pass along some history. The Pittsburgh ACE is squarely in Pittsburgh’s East End which is comprised of the Point Breeze, Highland Park, Shadyside and East Liberty neighborhoods. The East End’s heyday was around 1900 when it was the world’s richest neighborhood whose inhabitants controlled 40% of the nation’s assets. In 1900 more millionaires lived in Pittsburgh’s East End than anywhere on earth. It would not be uncommon at that time to take a walk along Penn Avenue and see a Carnegie or Frick (steel), H.J. Heinz (pickles), George Westinghouse (airbrakes, natural gas & electricity), Richard or Andrew Mellon (banking), Alfred Hunt (founder of ALCOA aluminum), Robert Pitcairn (founder of PPG glass), Charles Lockhart (co-founder of Rockefeller’s Standard oil), Thomas Armstrong (cork), James McCrea (president of the Pennsylvania Railroad), James Guffey (founder of Gulf Oil), Charles Schwab (first president of J.P. Morgan’s United States Steel Corporation), Henry Laughlin (Jones & Laughlin Steel), Lillian Russell (national theatre star) or a congressman, an ambassador or cabinet secretary and many others of wealth and influence. Before the Civil War East Liberty was a village with rural charm. -

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA SOUTH, EAST, AND WEST BUSWAYS Table of Contents PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA (USA) ..........................................1 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................. 1 CITY CONTEXT......................................................................................................................... 1 PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION BACKGROUND.................................................................. 2 THE EARLY ACTION PLAN ................................................................................................... 2 South Busway................................................................................................................ 3 East Busway.................................................................................................................. 3 West Busway ................................................................................................................. 4 THE BUSWAY SYSTEM – PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................... 5 OVERVIEW OF BUSWAYS..................................................................................................... 5 South Busway................................................................................................................ 5 East Busway.................................................................................................................. 6 East Busway Extension ................................................................................................ -

Development for Your Transit Dollar

More Development For Your Transit Dollar An Analysis of 21 North American Transit Corridors By Walter Hook, Stephanie Lotshaw, and Annie Weinstock MORE DEVELOPMENT FOR YOUR TRANSIT DOLLAR 1 2 MORE DEVELOPMENT FOR YOUR TRANSIT DOLLAR More Development For Your Transit Dollar An Analysis of 21 North American Transit Corridors By Walter Hook, Stephanie Lotshaw, and Annie Weinstock More Development for Your Transit Dollar: An Analysis of 21 North American Transit Corridors Cover Photo: Cleveland’s HealthLine BRT has helped leverage $5.8 billion dollars of TOD investment since its opening in 2008. Cover Photo By: Matthew Collins with support from 9 East 19th Street, 7th Floor, New York, NY, 10003 tel +1 212 629 8001 www.itdp.org CONTENTS Executive Summary 6 chapter 3 Government Interventions 57 Acronyms and Abbreviations 16 Agencies, Authorities, and Other Institutions 58 Regional Planning Agencies 59 Introduction 14 Redevelopment Authorities 60 City and State Agencies and Transit Authorities 66 chapter 1 Community Development Corporations 68 Mass Transit Options for TOD 18 Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) 69 BRT, LRT, and Streetcar 19 Other Community-level Nonprofits 70 Comparing the Costs 20 Foundations 70 Comparing the Capacities 22 Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) 70 Comparing Speeds and Operations 24 Comprehensive Planning 72 Comparing Ridership 36 Station–area Planning 75 Implementation Speed, Phasing, 28 Zoning 76 and Environmental Impacts Citywide Zoning Codes 77 Assessing the Quality of Surface Mass Transit 30 Area-specific -

Pittsburgh's Railroads

10/31/2014 From Boxcars to Buses: Use of Railroad Rights-of-Way for Transit in Pittsburgh David E. Wohlwill, AICP Port Authority of Allegheny County American Planning Association – Pennsylvania Chapter Philadelphia, PA October 12, 2014 Pittsburgh’s Railroads Pennsylvania Railroad entered Pittsburgh in 1852. Became the largest railroad serving Pittsburgh Other major railroads serving Pittsburgh: • Baltimore & Ohio • Pittsburgh & Lake Erie • Pittsburgh & West Virginia/Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal (Last railroad to Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania enter Pittsburgh) 1 10/31/2014 Extensive network of railroad lines developed in Pittsburgh by the 1900s Portion of Pittsburgh & Lake Erie RR Map Railsandtrails.com Railroads’ Vast Physical Plant CM Interlocking in East Liberty Pennsylvania Station Track Layout Broadway.pennsyrr.com/Rail/Prr/ 2 10/31/2014 PRR’s rail infrastructure in Pittsburgh • To accommodate increased freight and passenger traffic busiest lines were widened to four tracks • These lines were also grade separated in elevated and depressed alignments • Wide rights-of-way and grade separation subsequently facilitated use of PRR rail corridors for transit usage Both images: University of Pittsburgh Howard Fogg, Author’s collection 3 10/31/2014 Mid 20th Century Changes in the Pittsburgh Region and Rail Corridors • Pittsburgh region became economically mature in the 1920s • Lineside industries relocate to other areas or go out of business (Ford Motor plant ceases production in 1932) • City of Pittsburgh reaches its peak population -

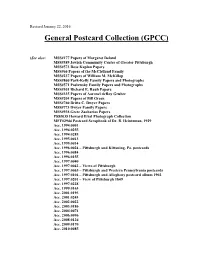

Postcard Collection Library

Revised January 22, 2016 General Postcard Collection (GPCC) (See also: MSS#177 Papers of Margaret Deland MSS#389 Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh MSS#573 Rose Kaplan Papers MSS#66 Papers of the McClelland Family MSS#237 Papers of William M. McKillop MSS#860 Park-Kelly Family Papers and Photographs MSS#571 Paslawsky Family Papers and Photographs MSS#301 Richard E. Rauh Papers MSS#335 Papers of Aaronel deRoy Gruber MSS#204 Papers of Bill Green MSS#760 Britta C. Dwyer Papers MSS#773 Dwyer Family Papers MSS#938 Grete Zacharias Papers PSS#035 Howard Etzel Photograph Collection MFF#2944 Postcard Scrapbook of Dr. B. Heintzman, 1929 Acc. 1994.0001 Acc. 1994.0255 Acc. 1994.0285 Acc. 1995.0013 Acc. 1995.0014 Acc. 1996.0024 – Pittsburgh and Kittaning, Pa. postcards Acc. 1996.0084 Acc. 1996.0155 Acc. 1997.0040 Acc. 1997.0042 – Views of Pittsburgh Acc. 1997.0065 – Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania postcards Acc. 1997.0104 – Pittsburgh and Allegheny postcard album 1902 Acc. 1997.0201 – View of Pittsburgh 1849 Acc. 1997.0228 Acc. 1999.0163 Acc. 2001.0195 Acc. 2001.0243 Acc. 2002.0022 Acc. 2003.0186 Acc. 2004.0074 Acc. 2006.0096 Acc. 2008.0126 Acc. 2009.0170 Acc. 2010.0085 Postcard Collection Inventory, Page # 2 of 81 Acc. 2011.0171 – Interesting Views of Pittsburgh postcard book Acc. 2011.0218 – Pittsburgh and Western Pa. Acc. 2011.0292 – Gateway Center, Point, Downtown Acc. 2014.0017) (Book Resources: Search Postcard History Series in catalog Greetings from Pittsburgh: A Picture Postcard History/Ralph Ashworth - F159.3.P643 A84 1992 q A Pennsylvania Album: picture postcards 1900-1930/George Miller - F150.M648 long Riverlife: Postcards from the Rivers/Riverlife Task Force – HT177 .P5 P6 2002 long Box 1 Pittsburgh Aviaries Conservatory Aviary Churches All Saints Episcopal- Allegheny Bethany Evangelical Lutheran- East Liberty Bethel Presbyterian Calvary Episcopal – Shady/Walnut Calvary United Methodist – North Side Christ Evangelical Lutheran-East End Christ Church of the Ascension – Ellsworth & Neville Christ M.E. -

Pittsburgh Architecture Information File

Pittsburgh Architecture 1000 California (Northside) 1000 Grandview Condominiums 121 Ninth St. 1370 Washington Pike (Bridgeville) 146 45th St. (Lawrenceville) 1902 Landmark Tavern 200 West North Ave. (Northside) 411 Grand Plaza 415 Stratton Lane (Shadyside) 518 Emerson St. 525 William Penn Place (Mellon Building) 5742 Fifth Ave. Condos 5807 Fifth Ave. Condos 614 Bellefont Street (Shadyside) 6568 Fifth Ave. (Point Breeze) 826 Lincoln Ave. 841 N. Lincoln Ave (Northside) Academy Place (Glen Osborne) Air Tool Parts and Service Co. (Smallman St) Airport Alcoa Building (Downtown) Alcoa Building (Northside) Alcoa Building (proposed, East General Robinson St., Northside) Alequippa Terrace All Saints Church (Etna) Allegheny Cemetery Allegheny City Hall Allegheny Community College Allegheny County Airport Allegheny County Courthouse & Jail Allegheny County Morgue Allegheny General Hospital Allegheny International Inc. Proposed Headquarters Allegheny Observatory Allegheny Tower Apartments Allegheny West (Northside) Allegheny-Kiski Valley Heritage Museum (Tarentum) Allison Elementary School (Wilkinsburg) Alpha Terrace (Highland Park) Aluise, John & Angela House (Bellevue) Aluminum Company of America Building Alzheimer?s Alliance Care & Research Center (proposed) American Institute of Architects Ammons, Tom Home (Hampton Twp.) Anderson Manor (Manchester) Apartment Building (Alder & S. Highland) Apartment House (Shadyside) APICS Castle Appletree Bed & Breakfast Architects Workshop Architectural Club Armstrong Cork Co. ? Armstrong Square (Strip District) Armstrong, Richard House Armstrong, Robert III (Covert Rd., Lawrence County near New Castle) Arrott Building (Downtown) Art Deco Art Moderne Arts & Crafts Aspinwall Presbyterian Church Atlantic Financial Building Atlantic Refining Co. Atrium (Oakland) Avery Church (Northside) Aviary Awards B?Nai Israel Synagogue (E. Liberty) Bair, Harry S. (East End Ave.) Baker, F. J. Torrance House (Sewickley) Ballay, Joe (Penn Hills) Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Bank of Pittsburgh (John Chislett, arch) Bank, The Barns Barrow, Joseph L.