Pittsburgh's East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls

Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls Jack E. Hauck Treasures of Wenham History, Helen Frick Pg. 441 Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls In Wenham, for forty-five years Helen Clay Frick devoted her time, her resources and her ideas for public good, focusing on improving the quality of life of young, working-class girls. Her style of philanthropy went beyond donating money: she participated in helping thousands of these girls. It all began in the spring of 1909, when twenty-year-old Helen Frick wrote letters to the South End Settlement House in Boston, and to the YMCAs and churches in Lowell, Lawrence and Lynn, requesting “ten promising needy Protestant girls to be selected for a free two-week stay ”in the countryside. s In June, she welcomed the first twenty-four young women, from Lawrence, to the Stillman Farm, in Beverly.2, 11 All told, sixty-two young women vacationed at Stillman Farm, that first summer, enjoying the fresh air, open spaces and companionship.2 Although Helen monitored every detail of the management and organization, she hired a Mrs. Stefert, a family friend from Pittsburgh, to cook meals and run the home.2 Afternoons were spent swimming on the ocean beach at her family’s summer house, Eagle Rock, taking tea in the gardens, or going to Hamilton to watch a horse show or polo game, at the Myopia Hunt Club.2 One can only imagine how awestruck these young women were upon visiting the Eagle Rock summer home. It was a huge stone mansion, with over a hundred rooms, expansive gardens and a broad view of the Atlantic Ocean. -

Reading Guide in Sunlight, in a Beautiful Garden

Reading Guide In Sunlight, in a Beautiful Garden By Kathleen Cambor ISBN: 9780060007577 Johnstown, Pennsylvania 1889 So deeply sheltered and surrounded was the site that it was as if nature's true intent had been to hide the place, to keep men from it, to let the mountains block the light and the trees grow as thick and gnarled as the thorn-dense vines that inundated Sleeping Beauty's castle. Perhaps, some would say, years later, that was central to all that happened. That it was a city that was never meant to be. IntroductionOn May 31, 1889, the unthinkable happened. The dam supporting an artificial lake at the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, playground to wealthy and powerful financiers Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and Andrew Mellon, collapsed. It was one of the greatest disasters in post-Civil War America. Some 2,200 lives were lost in the Johnstown, Pennsylvania, flood. In the shadow of the Johnstown dam live Frank and Julia Fallon, devastated by the loss of two children; their surviving son, Daniel, a passionate opponent of industrial greed; Grace McIntyre, a newcomer with a secret; and Nora Talbot, a lawyer's daughter, who is both bound to and excluded from the club's society. As Frank and Julia, seemingly incapable of repairing their marriage, look to Grace for solace and friendship, Daniel finds himself inexplicably drawn to Nora, daughter of a wealthy family from Pittsburgh. James, Nora's father, struggles with his conscience after bending the law to file the club's charter and becomes increasingly concerned about the safety of the dam. -

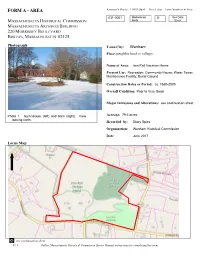

FORM a - AREA Assessor’S Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area

FORM A - AREA Assessor’s Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area 031-0001 Marblehead G See Data MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION North Sheet ASSACHUSETTS RCHIVES UILDING M A B 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Photograph Town/City: Wenham Place (neighborhood or village): Name of Area: Iron Rail Vacation Home Present Use: Recreation; Community House; Water Tower; Maintenance Facility; Burial Ground Construction Dates or Period: ca. 1880-2009 Overall Condition: Poor to Very Good Major Intrusions and Alterations: see continuation sheet Photo 1. Gymnasium (left) and barn (right). View Acreage: 79.6 acres looking north. Recorded by: Stacy Spies Organization: Wenham Historical Commission Date: June 2017 Locus Map see continuation sheet 4 /1 1 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM A CONTINUATION SHEET WENHAM IRON RAIL VACATION HOME MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area Letter Form Nos. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 G See Data Sheet Recommended for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. If checked, you must attach a completed National Register Criteria Statement form. Use as much space as necessary to complete the following entries, allowing text to flow onto additional continuation sheets. ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION Describe architectural, structural and landscape features and evaluate in terms of other areas within the community. The Iron Rail Vacation Home property at 91 Grapevine Road is comprised of buildings and landscape features dating from the multiple owners and uses of the property over the 150 years. The extensive property contains shallow rises surrounded by wetlands. Woodlands are located at the north half of the property and wetlands are located at the northwest and central portions of the property. -

Worker Resistance to Company Unions: the Employe Representation Plan of the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1920-1935

WORKER RESISTANCE TO COMPANY UNIONS: THE EMPLOYE REPRESENTATION PLAN OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD, 1920-1935 Albert Churella Southern Polytechnic State University Panel: Railway Organisations and the Responses of Capitalism and Governments, 1830-1940: A National and Internationally Comparative View William Wallace Atterbury, the PRR Vice-President in Charge of Operation, believed that a golden age of harmony between management and labor had existed prior to the period of federal government control of the railway industry, during and immediately after World War I. Following the Outlaw Strike of 1920, Atterbury attempted to recreate that mythic golden age through the Employe Representation Plan. Workers, however, saw the Employe Representation Plan for the company union that it was, ultimately leading to far more serious labor-management confrontations. Illustration 1 originally appeared in the Machinists’ Monthly Journal 35 (May 1923), 235. Introduction The vicious railway strikes that tore across the United States in 1877 marked the emergence of class conflict in the United States. They also shattered the illusion that the managers and employees of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) shared a common bond of familial loyalty and dedication to their Company. For the next forty years, PRR executives attempted to reestablish that sense of loyalty, harkening back to an imagined pre-industrial past, redolent with harmony and cooperation. As late as 1926, the PRR’s treasurer, Albert J. County, spoke for his fellow executives when he suggested that “the Chief problems of human relations in our time, as affecting the great transportation systems and manufacturing plants, have therefore been to find effective substitutes for that vanished personal contact between management and men, to the end that the old feeling of unity and partnership, which under favorable conditions spontaneously existed when the enterprises were smaller, might be restored.”1 PRR executives attempted to recreate “the old feeling of unity and partnership” with periodic doses of welfare capitalism. -

Railroad Postcards Collection 1995.229

Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Railroad stations .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Alabama ................................................................................................................................................... -

GSP NEWSLETTER Finding Your Pennsylvania Ancestors

September 2020 Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania Newsletter GSP NEWSLETTER Finding Your Pennsylvania Ancestors Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania Newsletter In this issue MESSAGE FROM GSP’S PRESIDENT • Library update.…..…………2 Working Hard Behind the Scenes • Did You Know? …………….2 The Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania (GSP) is currently • First Families Corner………3 working on the Sharla Solt Kistler Collection, which was • County Spotlight: donated to GSP by Mrs. Sharla Solt Kistler. Mrs. Kistler was an Columbia……………………4 avid genealogist with a vast collection of books and records reflecting her years of research. She donated her collection to • GSP members’ Civil War GSP so that her work and passion could be shared. ancestors…………….….…..5 • Q&A: DNA ..…………………9 The collection represents Mrs. Kistler’s many years of research • Tell Us About It………….…10 on her ancestors, largely in the Lehigh Valley area of Eastern Pennsylvania. It includes her personal research and • PGM Excerpt: Identifying correspondence. Available are numerous transcriptions of 19th-century photographs church and cemetery records from Berks, Schuylkill, Lehigh, ………………………………11 and Northampton counties, as well as numerous books. Pennsylvanians of German ancestry are well represented in Update about GSP this collection. Volunteers are cataloging the collection and hoping to create Although our office is not yet finding aids for researchers to use both on site and online. open to visitors, staff is here on Monday, Tuesday, and Even though GSP’s library is still closed to visitors because of Thursday from 10 am to 3 pm the pandemic, volunteers are hard at work on this, as well as and can respond to your other projects. -

Patriots, Pioneers and Presidents Trail to Discover His Family to America in 1819, Settling in Cincinnati

25 PLACES TO VISIT TO PLACES 25 MAP TRAIL POCKET including James Logan plaque, High Street, Lurgan FROM ULSTER ULSTER-SCOTS AND THE DECLARATION THE WAR OF 1 TO AMERICA 2 COLONIAL AMERICA 3 OF INDEPENDENCE 4 INDEPENDENCE ULSTER-SCOTS, The Ulster-Scots have always been a transatlantic people. Our first attempted Ulster-Scots played key roles in the settlement, The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish contribution to the Patriot cause in the events The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish played important roles in the military aspects of emigration was in 1636 when Eagle Wing sailed from Groomsport for New England administration and defence of Colonial America. leading up to and including the American War of Independence was immense. the War of Independence. General Richard Montgomery was the descendant of SCOTCH-IRISH but was forced back by bad weather. It was 1718 when over 100 families from the Probably born in County Donegal, Rev. Charles Cummings (1732–1812), a a Scottish cleric who moved to County Donegal in the 1600s. At a later stage the AND SCOTS-IRISH Bann and Foyle river valleys successfully reached New England in what can be James Logan (1674-1751) of Lurgan, County Armagh, worked closely with the Penn family in the Presbyterian minister in south-western Virginia, is believed to have drafted the family acquired an estate at Convoy in this county. Montgomery fought for the regarded as the first organised migration to bring families to the New World. development of Pennsylvania, encouraging many Ulster families, whom he believed well suited to frontier Fincastle Resolutions of January 1775, which have been described as the first Revolutionaries and was killed at the Battle of Quebec in 1775. -

Andrew Carnegie: the Richest Man in the World Program Transcript

Page 1 Andrew Carnegie: The Richest Man in the World Program Transcript Narrator: For 700 years Scottish Bishops and Lords had reigned over Skibo Castle. In 1899 it passed to an American who had fled Scotland penniless. To Andrew Carnegie Skibo was "heaven on earth." "If Heaven is more beautiful than this," he joked, "someone has made a mistake." When Carnegie left Scotland at age 12, he was living with his family in one cramped room. He returned to 40,000 acres. And he wasn't yet the richest man in the world. Andrew Carnegie's life seemed touched by magic. Owen Dudley Edwards, Historian: Carnegie was more than most people. Not only more wealthy, not only more optimistic. In his case it goes almost to the point of unreality. Carnegie is still right throughout his life, the little boy in the fairy story, for whom everything has to be alright. Narrator: Carnegie was a legendary figure in his own time. A nineteenth century icon. He embodied the American dream - the immigrant who made it from rags to riches. Whose schoolhouse was the library. The democratic American whose house guests included Mark Twain, Booker T. Washington, Helen Keller, Rockefellers and royalty and the ordinary folks from his childhood. He would entertain them all together. Although he loved Scotland, he prized America as a land free from Britain's monarchy -- and inherited privilege. After King Edward VII visited Skibo, Carnegie told a friend all Americans are kings. But everyone knew there was only one king of steel. Harold Livesay, Historian: He set out literally to conquer the world of steel, and that he did and became the largest steel producer not only in the United States, but Carnegie Steel by 1900 produced more steel than the entire steel industry of Great Britain. -

Pa-Railroad-Shops-Works.Pdf

[)-/ a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania f;/~: ltmen~on IndvJ·h·;4 I lferifa5e fJr4Je~i Pl.EASE RETURNTO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER DENVER SERVICE CE~TER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CROFIL -·::1 a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania by John C. Paige may 1989 AMERICA'S INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE PROJECT UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR I NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CONTENTS Acknowledgements v Chapter 1 : History of the Altoona Railroad Shops 1. The Allegheny Mountains Prior to the Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 1 2. The Creation and Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 3 3. The Selection of the Townsite of Altoona 4 4. The First Pennsylvania Railroad Shops 5 5. The Development of the Altoona Railroad Shops Prior to the Civil War 7 6. The Impact of the Civil War on the Altoona Railroad Shops 9 7. The Altoona Railroad Shops After the Civil War 12 8. The Construction of the Juniata Shops 18 9. The Early 1900s and the Railroad Shops Expansion 22 1O. The Railroad Shops During and After World War I 24 11. The Impact of the Great Depression on the Railroad Shops 28 12. The Railroad Shops During World War II 33 13. Changes After World War II 35 14. The Elimination of the Older Railroad Shop Buildings in the 1960s and After 37 Chapter 2: The Products of the Altoona Railroad Shops 41 1. Railroad Cars and Iron Products from 1850 Until 1952 41 2. Locomotives from the 1860s Until the 1980s 52 3. Specialty Items 65 4. -

The Business Career of Henry Clay Frick

2 T «\u25a0 •8 Pittsburgh History, Spring 1990 as functioning parts ofa nationwide economic organ- isation. The United States became the world's biggest economy and then, for the first time, a major factor in the direction of commercial operations beyond its own boundaries. Inshort, Prick's career covered both the nationalising and the internationalising ofAmeri- can business. Athis birth the U.S. economy was still small compared to the United Kingdom's; bythe end ofhis life itwas far ahead. (Appendix, page 14, Table I)This growth was uneven, for the pace ofeconomic development varies over time.(The parts ofthenation where it occurs most intensely also vary, of course, over time.) Such development originates with the actions of human beings, and while few individuals can do more than respond to it,in doing so they to some extent guide and help tolocalise it. American growth at its various stages depended on different types of activities, which for a range of reasons were conducted in different regions; it was the good fortune of Frick and his close associates that the phase of development with which their lives coincided was par- ticularly suited to the physical en- dowment and location of Western Pennsylvania. Circumstances pro- vided the opportunities; successful regional entrepreneurs recognized and seized them. Consider for a moment economic historian Walt Rostow's model of national devel- opment, described inhis The Stages ofEconomic Growth: a 'Ron-Com- munist Manifesto (1971 ), in which the take-off stage involves textiles and the early railway age, and is above all focused in New England been unkind tohim. -

PHLF News Publication

Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation 450 The Landmarks Building One Station Square Pittsburgh, PA 15219-1170 Address Correction Requested Published for the members of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation No. ll4 Summer 1990 a Preservation Fund at Work a Summer Family Fun a The History and Architecture of Allegheny CemeterY l.lnion I{øtionøl Augmßnts Preseruøtion Fund Pitxbørgh Cornrnanity Reinaestnaent Grouþ Allegbery lYe¡¡ Cittic Council B I o o rnfi e I d / Garf e / d C orþ orø tio n Breøobmenders, Ini.' Calbride Pløce Citizen¡ Council , Central Nortltsidc Neighborbood Coancil i; Cbarles Street Areø Coxncil' , Eait.Alleglteny Commtni4 Council ¡i, , \ .."' East Libe¡t Deaelopnenì, Inc. ç'' *ila ía;,7;;,1!,.1:¡j',,,,',, icàr¡ttd¡obilee ¡ 'i-'i.:... A¡¡ociøtioît ... " ,'' Hill Co**ani4 DeyeloPmcnt Corþ. i , Ho*euood Bntsltton Reaitatizøtion l- - and.Deaeloþncnl Corþorøtiox fur' Iørrtoceuille Citizens Council T.ffi #:,;i?;':'r,,iz e n s c orþ orat i o n Nott h si dà^ C íaic Dettelop men t Co an c il N ort h s i de I¿ ød¿ rt à iP C o nfe re n c e ' î$ff* NorthsiùTënanßReorganizalion *frHffip* Obseruatory Hill ''' .Oaäland Planning Er Detteloþnent ' CorPorøtion Peny Hilltoþ Citizens Council , l Co, Soath Sidc I'ocøl DaaeloPtnent , Spring Garfux Neiglt borhood Cotncil Trol Hitt Citizens Coancil Rigltt: 'A Samþler": IJaion Nøtional reports on itr fnt lcdr of uorà uitb the PCRG. Tlte ncighborhood scene øboae is of Resaca Pldcc in the Meicøn Wør Strcets. '{@ n March 30, Union National "It's an honor to work with Landmarks Bank and the Pittsburgh to further the efforts of Union National History & Landmarks Bank to assist people in Pittsburgh's low- Foundation announced joint and moderate-income nei ghborhoods," said efforts to provide low- Gayland B. -

East Liberty Mellon Bank

HISTORIC REVIEW COMMISSION Division of Development Administration and Review City of Pittsburgh, Department of City Planning 200 Ross Street, Third Floor Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15219 INDIVIDUAL PROPERTY HISTORIC NOMINATION FORM Fee Schedule HRC Staff Use Only Please make check payable to Treasurer, City of Pittsburgh Date Received: .................................................. Individual Landmark Nomination: $100.00 Parcel No.: ........................................................ District Nomination: $250.00 Ward: ................................................................ Zoning Classification: ...................................... 1. HISTORIC NAME OF PROPERTY: Bldg. Inspector: ................................................ Council District: ............................................... former Mellon National Bank, East Liberty Office 2. CURRENT NAME OF PROPERTY: Citizens Bank, East Liberty Branch 3. LOCATION a. Street: 6112 Penn Avenue b. City, State, Zip Code: Pittsburgh, PA 15206 c. Neighborhood: East Liberty 4. OWNERSHIP d. Owner(s): ARC CBPBGPA010 LLC e. Street: 2325 E Camelback Road, Floor 9 f. City, State, Zip Code: Phoenix, AZ 85016-9080 Phone: (602) 778-6000 5. CLASSIFICATION AND USE – Check all that apply Type Ownership Current Use: Structure Private – home VACANT/NOT IN USE District Private – other Site Public – government Object Public - other Place of religious worship 1 6. NOMINATED BY: a. Name: Brittany Reilly b. Street: 1501 Reedsdale Street, Suite 5003 c. City, State, Zip: Pittsburgh, PA 15233 d. Phone: (412) 256-8755 Email: [email protected] 7. DESCRIPTION Provide a narrative description of the structure, district, site, or object. If it has been altered over time, indicate the date(s) and nature of the alteration(s). (Attach additional pages as needed) If Known: a. Year Built: 1969-1970 b. Architectural Style: Modernism (Functionalist) c. Architect/Builder: Liff, Justh and Chetlin Architects and Engineers Narrative: See attached 8. HISTORY Provide a history of the structure, district, site, or object.