Eastern Corridor Transit Study Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usair Rejected Contracts.Pdf

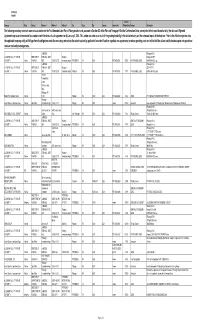

US Airways Exhibit 1 Contract Company Entity Contact Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 City State Zip Country Contract No. Effective Date Product Description The following executory contracts were not assumed under the First Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization and, pursuant to Section 8.2 of the Plan and Paragraph 18 of the Confirmation Order, are rejected effective on the earlier of (a) the date such Rejected Agreement expires or is terminated in accordance with the terms of such agreement or (b) January 5, 2004. This action was taken as a result of the growing instability in the airline industry and the unknown impact of the Iraqi war. Prior to the effective rejection date, the applicable company entity will fully perform its obligations under the executory contracts to the extent required by applicable law and will seek to negotiate new agreements to reduce operating costs and utilize facilities to best suit its business plan and operational needs or make other arrangements. LANDSIDE Pittsburgh, PA ALLEGHENY COUNTY AIRPORT DIRECTOR OF TERMINAL - SUITE Pittsburgh Hangar 3/4 #7977 AUTHORITY Mainline AVIATION 4000 PO BOX 12370 International Airport PITTSBURGH PA 15231 PIT 0463L00100 10/1/63 MAINTENANCE LEASE MAINTENANCE Lease LANDSIDE Pittsburgh, PA ALLEGHENY COUNTY AIRPORT DIRECTOR OF TERMINAL - SUITE Pittsburgh SSB #7977-B AUTHORITY Mainline AVIATION 4000 PO BOX 12370 International Airport Piitsburgh PA 15231 PIT 0473L00100 1/1/73 MAINTENANCE LEASE MAINTENANCE Lease National Transportation Center 534 Union Trust Bldg. Pittsburgh, PA National -

PIT VP Public Safety

The Airports & ACAA Allegheny County Airport Authority (ACAA) oversees and maintains Pittsburgh International Airport and Allegheny County Airport. Pittsburgh International Airport Pittsburgh International Airport (PIT) is in Findlay and Moon townships in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, about 20 miles west of downtown Pittsburgh. It is the second-busiest airport in Pennsylvania, after Philadelphia International Airport, serving nearly 9 million passengers in 2017. To manage growing passenger traffic, construction began on the original Greater Pittsburgh International Airport in 1946 and opened in 1952. Over time, as passenger traffic further increased, services were expanded both domestically and internationally. Allegheny County and ACAA undertook a major, nearly billion-dollar airport expansion in 1987. The new Pittsburgh International Airport opened in 1992 and has been ranked highly by travelers and industry journals. In January 2018, Air Transport World magazine named PIT its 2017 Airport of the Year, placing the airport in prestigious company alongside past winners Hong Kong International, London Heathrow and Singapore Changi. (continued...) page 2 The Airports & ACAA (continued) J.D. Power ranked Pittsburgh International in its Top 10 medium-size airports in its 2015 North American Airport Satisfaction Study. Travel + Leisure also named Pittsburgh International a Top 10 Domestic Airport in 2016. TripAdvisor ranked Pittsburgh International Airport a Traveler’s Choice Favorite for Shopping in 2016. Now, PIT is undergoing a Terminal Modernization Program which promises to positively change the air travel experience in and out of Pittsburgh for decades. In addition, by adding more nonstop flights, PIT has opened more of the nation and world to Pittsburgh for business and leisure travelers. -

Rules and Regulations

Rules and Regulations Rules & Regulations | 02.12.21 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................4 ARTICLE I: DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................6 ARTICLE II: GENERAL CONDUCT .................................................................... 12 ARTICLE III: DOING BUSINESS AT THE AIRPORT .......................................... 16 ARTICLE IV: COMMUNICATION ........................................................................ 24 ARTICLE V: APRON OPERATIONS................................................................... 26 ARTICLE VI: MOTOR VEHICLES ....................................................................... 28 ARTICLE VII: FIRE AND SAFETY ...................................................................... 37 ARTICLE VIII: ACAA TENANT AND CONTRACTOR FIRE POLICY AND HAZARDOUS MATERIAL ................................................................................... 41 ARTICLE IX: SANITATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL ......................................... 46 ARTICLE X: SECURITY ...................................................................................... 49 ARTICLE XI: FUELING ....................................................................................... 55 ARTICLE XII: WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT ........................................................... 66 ARTICLE XIII: DEFINITIONS, NOTICE OF VIOLATIONS, ENFORCEMENT / PENALTIES ............................................................................... -

Project Purpose and Need Statement June 2019

Norfolk Southern Railway Company Pittsburgh Vertical Clearance Projects Project Purpose and Need Statement June 2019 INTRODUCTION: These proposed projects are railway improvement projects on the Pittsburgh and Fort Wayne Rail Lines (together referred to as the Pittsburgh Line), owned and operated by Norfolk Southern Railway Company (NSR). The proposed projects consist of addressing freight capacity and delay constraints through the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. The Pittsburgh Line serves rail freight traffic in interstate commerce and operates as a primary link through Pittsburgh between Chicago and the New York/New Jersey commercial markets. NSR is a common carrier and the Pittsburgh Line forms a critical component of NSR’s route between Chicago and the east coast, carrying a variety of commodities, both hazardous material such as chlorine, anhydrous ammonia, hydrogen fluoride, crude oil, and ethanol, as well as nonhazardous materials like coal, auto parts and finished vehicles, lumber, agricultural products, and intermodal containers and trailers. The six overhead clearance projects [North Avenue Bridge, Pittsburgh (PC-1.60); Pennsylvania Avenue Bridge, Pittsburgh (PC-1.82); Columbus Avenue Bridge, Pittsburgh (PC-2.17); Ohio Connecting (OC) Bridge Flyover, Pittsburgh (PC-3.38); Washington Avenue Bridge, Swissvale (PT-344.91); and Amtrak Station Canopy (PT-353.20)] have vertical obstructions along the Pittsburgh Line and prevent efficient movement of freight, especially time-sensitive intermodal freight, by rail between Chicago and New York/New Jersey, and specifically through Pennsylvania. Unused capacity exists on the Pittsburgh Line and these clearance projects will allow the line to accommodate anticipated freight growth while allowing for double-stack intermodal freight to use the Pittsburgh Line in lieu of the Mon Line. -

See Questions and Replies at Bottom of RFP. REQUEST FOR

See questions and replies at bottom of RFP. REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (RFP) Wilkinsburg Transit Revitalization Investment District (TRID) Planning Study RFP Issue Date: June 15, 2017 Proposals Due Date: July 21, 2017 at 4 PM ET Section 1. General Information: 1.1 The Borough of Wilkinsburg requests proposals from transportation, economic development and urban planning consultants to author a planning study that identifies transit-oriented development and infrastructure opportunities in and near the Borough of Wilkinsburg within the vicinity of Allegheny County’s Martin Luther King, Jr. East Busway and examines the feasibility of creating a TRID district in the study area. 1.2 The project budget is $75,000. The project duration is estimated to be 12 months. Interested parties are requested to submit a detailed Proposal Package that clearly defines the relevant experience of the proposed staff and subconsultant team members, as well as proposed methods and strategy to carry out the project scope of work. 1.3 Contact person for all queries and for receipt of proposals: Donn Henderson 1 | Page Borough Manager Borough of Wilkinsburg 605 Ross Ave Wilkinsburg, PA 15221 412-244-2906 [email protected] 1.4 Respondents shall restrict all contact and questions regarding this RFP and selection process to the individual named herein. Questions concerning terms, conditions and technical specifications shall be directed in writing to Donn Henderson (See section 1.3). Questions will be answered in writing on the Borough of Wilkinsburg website under the rfp by June 30, 2017 (http://www.wilkinsburgpa.gov). Questions submitted after June 27, 2017 will not be answered. -

Railroad Postcards Collection 1995.229

Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Railroad stations .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Alabama ................................................................................................................................................... -

Annual Listing of Highway Projects with Federal Funding Obligated For

Annual Listing of Projects with Federal Funding Obligated for Fiscal Year 2018 Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission Two Chatham Center, Suite 500 112 Washington Place, Pittsburgh PA 15219 Phone (412) 391-4490 Fax (412) 391-9160 www.spcregion.org List of Abbreviations and Definitions FAST ACT Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act FHWA Federal Highway Administration FTA Federal Transit Administration MPO Metropolitan Planning Organization MPMS Multi-modal Project Management System One Map PennDOT Public Mapping Application PennDOT Pennsylvania Departmnet of Transportation SPC Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission TIP Transportation Improvement Program Project Funding Codes ARC Appalachian Regional Commission BOF Bridge - Off System BOO, BON Federal Bridge Funds CAQ Congestion Mitigation and Air Wuality FAP Slide Emergency HSIP Highway Safety Improvement Program NHPP National Highway Performance Program RRX Surface Transportation - RRX Elimination of Crossing Special Project SFX Special Project - Federal Earmark STP Surface Transportation - Any Area in State STU Surface Transportation - Urban TAP Transportation Alternatives Program Project Phase Abbreviations CON Construction FD Final Design Preliminary PE Engineering Right of ROW Way UTL Utilities 1 Annual Listing of Federally Obligated Highway Projects October 1, 2017 to September 30, 2018 Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission Annual Listing of Projects with Federal Funding Obligated for Federal Fiscal Year 2018 On December 4th, 2015, President Obama signed into law the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act) which allocates federal funding for surface transportation programs over fiscal years 2016 through 2020. Per 23 U.S.C. § 134(j)(7)(B) of FAST Act, states and Metropolitan Planning Organizations (such as the SPC) must publish annual lists of projects where federal funds were obligated. -

Guiding Change in the Strip

Guiding Change in the Strip Capstone Seminar in Economic Development, Policy and Planning Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) University of Pittsburgh December 2002 GUIDING CHANGE IN THE STRIP University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public and International Affairs Capstone Seminar Fall 2002 Contributing Authors: Trey Barbour Sherri Barrier Carter Bova Michael Carrigan Renee Cox Jeremy Fine Lindsay Green Jessica Hatherill Kelly Hoffman Starry Kennedy Deb Langer Beth McCall Beth McDowell Jamie Van Epps Instructor: Professor Sabina Deitrick i ii MAJOR FINDINGS This report highlights the ongoing nature of the economic, social and environmental issues in the Strip District and presents specific recommendations for Neighbors in the Strip (NITS) and policy makers to alleviate problems hindering community development. By offering a multitude of options for decision-makers, the report can serve as a tool for guiding change in the Strip District. Following is a summary of the major findings presented in Guiding Change in the Strip: • The Strip has a small residential population. As of 2000, the population was on 266 residents. Of these residents, there is a significant income gap: There are no residents earning between $25,000 and $35,000 annually. In other words, there are a limited amount of middle-income residents. Furthermore, nearly three-quarters of the 58 families living in the Strip earned less than $25,000 in 1999. These figures represent a segment of the residential population with limited voice in the development of the Strip. There is an opportunity for NITS, in collaboration with the City of Pittsburgh, to increase the presence of these residents in the future of the Strip. -

P78 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

P78 bus time schedule & line map P78 Downtown View In Website Mode The P78 bus line (Downtown) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Downtown: 4:52 AM - 7:58 PM (2) Oakmont: 5:40 AM - 8:45 PM (3) Oakmont: 8:38 AM - 8:39 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest P78 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next P78 bus arriving. Direction: Downtown P78 bus Time Schedule 74 stops Downtown Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:52 AM - 7:58 PM Alpha Dr + Freeport Rd (Harmar) 2871 Freeport Rd, Harmar Tuesday 4:52 AM - 7:58 PM Freeport Rd + Alpha Dr W Wednesday 4:52 AM - 7:58 PM Freeport Road, Harmar Thursday 4:52 AM - 7:58 PM Freeport Rd + Target (Harmar) Friday 4:52 AM - 7:58 PM Freeport Road, Harmar Saturday Not Operational Freeport Rd + Valley Motel 2569 Freeport Rd, Harmar Freeport Rd + Guys Run Rd 2501 Freeport Rd, Harmar P78 bus Info Direction: Downtown Freeport Rd + #2366 Stops: 74 2366 Freeport Rd, Harmar Trip Duration: 51 min Line Summary: Alpha Dr + Freeport Rd (Harmar), Hulton Rd + Riverview Hs Freeport Rd + Alpha Dr W, Freeport Rd + Target 2 2nd Street Ext, Harmar (Harmar), Freeport Rd + Valley Motel, Freeport Rd + Guys Run Rd, Freeport Rd + #2366, Hulton Rd + Allegheny Ave + Archie Ns Riverview Hs, Allegheny Ave + Archie Ns, Allegheny 803 Allegheny Ave, Harmar Ave + Pennsylvania, Allegheny Ave + Ann Ns, Allegheny Ave + Maryland, Allegheny Ave + Delaware, Allegheny Ave + Pennsylvania Allegheny Ave + Washington, Allegheny Ave + 701 Allegheny Ave, Harmar College, Allegheny -

![4910-06-P DEPARTMENT of TRANSPORTATION Federal Railroad Administration [Docket Number FRA-2015-0019] Petition for Waiver of Comp](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3016/4910-06-p-department-of-transportation-federal-railroad-administration-docket-number-fra-2015-0019-petition-for-waiver-of-comp-493016.webp)

4910-06-P DEPARTMENT of TRANSPORTATION Federal Railroad Administration [Docket Number FRA-2015-0019] Petition for Waiver of Comp

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 04/03/2015 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2015-07617, and on FDsys.gov 4910-06-P DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Federal Railroad Administration [Docket Number FRA-2015-0019] Petition for Waiver of Compliance In accordance with part 211 of Title 49 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), this provides the public notice that by a document dated February 27, 2015, Norfolk Southern Corporation (NS) has petitioned the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) for a waiver of compliance from certain provisions of the Federal railroad safety regulations contained at 49 CFR part 213. FRA assigned the petition Docket Number FRA-2015-0019. Pursuant to 49 CFR 213.113(a), NS requests a waiver from the accepted practice of stop/start rail testing to start a pilot test process for nonstop continuous testing. The projected starting date for implementing the test process would be May 1, 2015, for a period of 3 years. The test process will commence initially on the main tracks of the Dearborn Division Chicago Line (Cleveland, OH, to Chicago, IL, Milepost (MP) CD 181.2–523.3). Once this district has been completed, NS will expand to the following locations: (1) Dearborn Division Cleveland Line (Ravenna to Drawbridge, MP RD 85.9– 123.2), Chicago District (Chicago, IL, to Hobart, IN, MP B 518.7–486.5), Lake Erie District (Euclid to Bay Village B 172.0–197.3); (2) Lake Division Chicago, Fostoria, & 2 Cleveland Districts (Hobart, IN, to Bay Village, OH, MP B 486.5–197.3); (3) -

Federal Register/Vol. 76, No. 135/Thursday, July 14, 2011/Notices

41556 Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 135 / Thursday, July 14, 2011 / Notices Mississippi Department of trains and engines between CP Bloom at online at http://www.dot.gov/ Transportation, Environmental MP–PT 351.6 near Pittsburg, PA and CP privacy.html. Division, 401 North West Street, Solomon. Issued in Washington, DC on July 7, 2011. • Operations on the Fort Wayne Line, Jackson, MS 39201. Robert C. Lauby, Mississippi Department of Pittsburgh Division from CP Rochester at MP–PC 29.5, near East Rochester, PA Deputy Associate Administrator for Transportation, First District Regulatory & Legislative Operations. Headquarters, 1901 N. Gloster Street, to CP Alliance at MP–PC 83.2. Tupelo, MS 38803. • Operations on the Conemaugh Line, [FR Doc. 2011–17681 Filed 7–13–11; 8:45 am] Federal Railroad Administration, Region Pittsburgh Division from CP Conpit at BILLING CODE 4910–06–P 3, 61 Forsyth Street—Suite 16T20, MP–LC 0.0, near Bolivar, PA to CP Kiski at MP–LC 47.8, near Freeport, PA. Atlanta, GA 30303–3104. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION In addition, electronic versions of the A copy of the petition, as well as any Draft EIS and appendices are available written communications concerning the Federal Railroad Administration through FRA’s Web site at http:// petition, is available for review online at www.fra.dot.gov/rpd/freight/3002.shtml http://www.regulations.gov and in [Docket Number FRA–2009–0052] person at the Department of and the MDOT Web site at http:// Petition for Waiver of Compliance www.gomdot.com/Home/Projects/ Transportation’s Docket Operations Studies/Northern/ Facility, 1200 New Jersey Ave., SE., In accordance with Part 211 of Title TupeloRailroadRelocation/Home.aspx. -

Resolution Agreement

RESOLUTION AGREEMENT Between the u.s. Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights and The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Transaction Number: 10-106043 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Parties to the Agreement III. Jurisdiction 1 IV. Background 1 V. Purpose of Agreement 2 VI. General Provisions 3 VII. Specific Provisions 5 A. Access to Health Care Services 5 B. Supplementation ofCurrently Available Transportation Services 12 C. Community Outreach and Communication 16 VIII. Reporting Requirements 17 IX. Signatures 19 Appendix A. Risk Assessment Questions 20 I. Introduction This Resolution Agreement (hereinafter "Agreement") is entered into by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Civil Rights (hereinafter "OCR"), and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (hereinafter "UPMC"), a Pennsylvania non-profit corporation. This Agreement resolves a complaint, OCR transaction number 10-106043 ("Complaint"), filed with the Department of Justice on November 20, 2009 and received by OCR on December 15, 2009, by Mr. Jesse Brown, the Braddock Borough Council President, through his attorney Mr. Lawrence Shields, III. The Complaint alleged that the closure of UPMC Braddock hospital will have a disproportionate or disparate impact or effect upon the African American population living in Braddock. II. Parties to the Agreement 1. The United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Civil Rights; and 2. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, a Pennsylvania non-profit corporation. III. Jurisdiction UPMC receives Federal financial assistance through its participation in the Medicare and Medicaid programs and is subject to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,42 U.S.C.