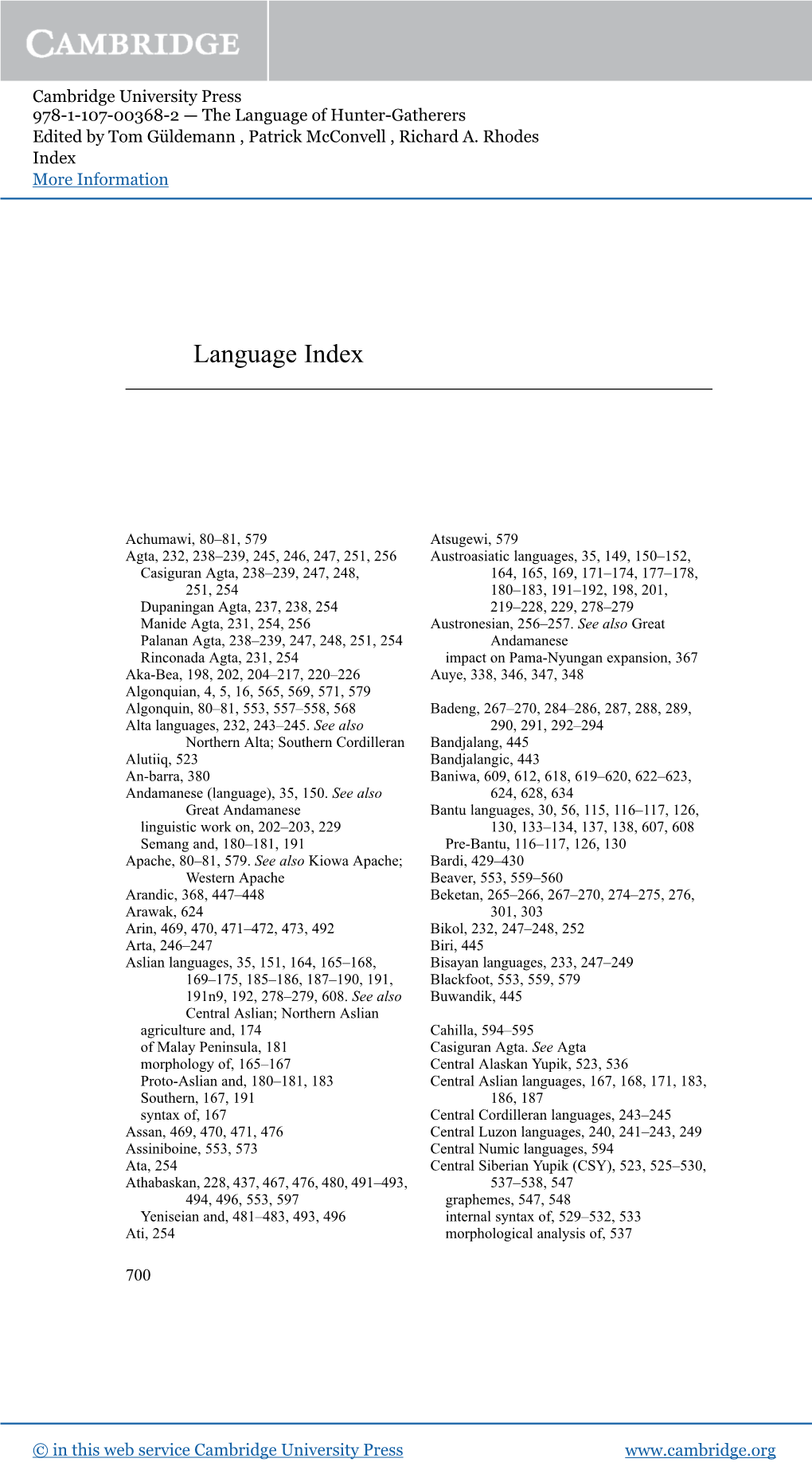

Language Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

The Response of the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol21, No 6, pp 977 – 988, 2000 Globalizationand democratization: the responseo ftheindigenous peoples o f Sarawak SABIHAHOSMAN ABSTRACT Globalizationis amulti-layered anddialectical process involving two consequenttendencies— homogenizing and particularizing— at the same time. Thequestion of howand in whatways these contendingforces operatein Sarawakand in Malaysiaas awholeis therefore crucial in aneffort to capture this dynamic.This article examinesthe impactof globalizationon the democra- tization process andother domestic political activities of the indigenouspeoples (IPs)of Sarawak.It shows howthe democratizationprocess canbe anempower- ingone, thus enablingthe actors to managethe effects ofglobalization in their lives. Thecon ict betweenthe IPsandthe state againstthe depletionof the tropical rainforest is manifested in the form of blockadesand unlawful occu- pationof state landby the former as aform of resistance andprotest. Insome situations the federal andstate governmentshave treated this actionas aserious globalissue betweenthe international NGOsandthe Malaysian/Sarawakgovern- ment.In this case globalizationhas affected boththe nation-state andthe IPs in different ways.Globalization has triggered agreater awareness of self-empow- erment anddemocratization among the IPs. These are importantforces in capturingsome aspects of globalizationat the local level. Globalization is amulti-layered anddialectical process involvingboth homoge- nization andparticularization, ie the rise oflocalism in politics, economics, -

Language of the Jungle

Language of The Jungle Oil on Canvas Sigang Kesei (Detail) Sigang Kesei 2013 Tan Wei Kheng December 17 – 31 2014 Has the jungle become more beautiful? The artist Tan Wei Kheng paints portraits of the unseen heroes of the nomadic Penan tribe in Sarawak, Malaysia. He invites us to discover the values and dreams of the Penans, who continue with their struggles in order to live close to nature. Tan is also involved in other initiatives and often brings with him rudimentary Language Of supplies for the Penans such as rice, sugar, tee shirts, and toothpaste. As natural – Ong Jo-Lene resources are destroyed, they now require supplements from the modern world. The Jungle Kuala Lumpur, 2014 Hunts do not bear bearded wild pigs, barking deers and macaques as often anymore. Now hunting takes a longer time and yields smaller animals. They fear that the depletion of the tajem tree from which they derive poison for their darts. The antidote too is from one specific type of creeper. The particular palm tree that provides leaves for their roofs can no longer be found. Now they resort to buying tarpaulin for roofing, which they have to carry with them every time they move Painting the indigenous peoples of Sarawak is but one aspect of the relationship from camp to camp. Wild sago too is getting scarcer. The Penans have to resort to that self-taught artist, Tan Wei Kheng has forged with the tribal communities. It is a farming or buying, both of which need money that they do not have. -

Adaptation to Climate Change: Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Hold the Key?

sustainability Article Adaptation to Climate Change: Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Hold the Key? Nadzirah Hosen 1,* , Hitoshi Nakamura 2 and Amran Hamzah 3 1 Graduate School of Engineering and Science, Shibaura Institute of Technology, Saitama City, Saitama 337-8570, Japan 2 Department of Planning, Architecture and Environmental Systems, Shibaura Institute of Technology, Saitama City, Saitama 337-8570, Japan; [email protected] 3 Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Built Environment and Surveying, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai 81310, Johor Bahru, Johor, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 December 2019; Accepted: 15 January 2020; Published: 16 January 2020 Abstract: The traditional knowledge of indigenous people is often neglected despite its significance in combating climate change. This study uncovers the potential of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) from the perspective of indigenous communities in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, and explores how TEK helps them to observe and respond to local climate change. Data were collected through interviews and field work observations and analysed using thematic analysis based on the TEK framework. The results indicated that these communities have observed a significant increase in temperature, with uncertain weather and seasons. Consequently, drought and wildfires have had a substantial impact on their livelihoods. However, they have responded to this by managing their customary land and resources to ensure food and resource security, which provides a respectable example of the sustainable management of terrestrial and inland ecosystems. The social networks and institutions of indigenous communities enable collective action which strengthens the reciprocal relationships that they rely on when calamity strikes. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 05:11:55PM Via Free Access 174 Bibliography

Bibliography Ahmed, Sara 1997 ‘Intimate touches; Proximity and distance in international feminist dialogues’, Oxford Literary Review 19:19-46. Alvarez, Claude 1992 Science, development and violence; The revolt against modernity. Delhi: Oxford University Press. Barreirro, J. 1991 ‘Indigenous peoples are the “miners’ canary” of the human family’, in: B. Willers (ed.), Learning to listen to the land, pp. 199-201. Washington DC: Island. Barui, Fraser 2000 ‘Govt serious in helping Penan community’, Sarawak Tribune 16 Sep- tember. Blaikie, Piers and Harold Brookfield 1987 Land degradation and society. London: Methuen. Blowpipes and bulldozers 1988 ‘Blowpipes and bulldozers; A story of the Penan tribe and Bruno Mansur’. [Gaia Films.] Bourdieu, Pierre 1977 Outline of a theory of practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1979 Distinction; A social critique of the judgement of taste. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Brosius, J. Peter 1986 ‘River, forest and mountain; The Penan Gang landscape’, Sarawak Museum Journal 36:173-89. 1988 ‘A separate reality; Comments on Hoffman’s “The Punan; Hunters and gatherers of Borneo”’, Borneo Research Bulletin 20-2:81-106. 1991 ‘Foraging in tropical rainforests; The case of the Penan of Sarawak, East Malaysia (Borneo)’, Human Ecology 19-2:123-50. 1992 ‘Perspectives on Penan development in Sarawak’, Sarawak Gazette 119- 1:5-22. 1993 ‘Contrasting subsistence ecologies of Eastern and Western Penan foragers (Sarawak, East Malaysia)’, in: C.M. Hladik, A. Hladik, O.F. Linares, H. Pagezy, A. Semple and M. Hadley (eds), Tropical forests, people and food; Biocultural interactions and applications to development, pp. 515-22. -

Keynote Address Human Rights and the Environment: Common Ground

Keynote Address Human Rights and the Environment: Common Ground Kerry Kennedy Cuomot I want to thank Guido Calibresi, Jacki Hamilton, Jacob Scherr, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science for inviting me to Yale today, and I want to thank all of you for coming. As an international human rights attorney, I have focused my efforts on individuals who, in their pursuit of human rights, have stood up to govern- ment oppression at great personal risk. Many of these individuals have been imprisoned, tortured, or killed for their political beliefs. Untold numbers of journalists have been silenced, lawyers jailed, scientists stifled, and trade unionists crushed. What all of these brave individuals have in common is their commitment to justice, non-violence, and the rule of law. Like civil rights lawyers in the United States who look to the Bill of Rights under the Constitution to guide their practice, international human rights lawyers look to a number of international instruments for the laws by which we expect governments to abide. Most human rights norms are based upon the Universal Declaration of Human Rights1 and the International Covenants on human rights.2 The Declaration was signed in 1948 in reaction to the Nazi atrocities during World War II, and set forth principles which members of the United Nations agreed to recognize. The Covenants were drafted and signed a few years later, and they set forth specific rights which states are bound to uphold. If states violate the terms of the CoVenants, they can be brought before a tribunal and held accountable. -

Aethiopica 10 (2007) International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies

Aethiopica 10 (2007) International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies ________________________________________________________________ GRAZIANO SAV ߃ MAURO TOSCO, Universit¿ degli studi di Napoli ߋL߈Orientaleߌ Review article HAROLD C. FLEMING, Ongota: a Decisive Language in African Prehistory Aethiopica 10 (2007), 223߃232 ISSN: 1430߃1938 ________________________________________________________________ Published by UniversitÃt Hamburg Asien Afrika Institut, Abteilung Afrikanistik und £thiopistik Hiob Ludolf Zentrum fÛr £thiopistik Review article HAROLD C. FLEMING, Ongota: a Decisive Language in African Pre- history = Aethiopistische Forschungen 64. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. 2006. ix, 214 pp., 5 ill. Price: ߫ 78. ISBN: 3߃447߃05124߃8. GRAZIANO SAV ߃ MAURO TOSCO, Universit¿ degli studi di Napoli ߋL߈Orientaleߌ 1. Introduction Ongota is an unclassified language spoken by hunter-gatherer and partially pastoralists. According to local traditions, they have always been living isolated and shifting settlement quite often (Sav¿ ߃ Thubauville 2006). The language is the expression of a highly conservative culture and represents a unique source of historical information. It is probably the most endangered language in Ethiopia. The community, about 100, has by now adopted the neighbouring Cushitic language Ts߈amakko (Tsamai) as first language. Only about 15 elders speak their traditional language (Sav¿ ߃ Thubauville 2006). Bender (1994) includes Ongota among the ߋmystery languagesߌ of Ethio- pia, which are the languages whose classification remains unclear. Indeed, no scholar has been able to isolate the genetic features of Ongota and prove a definite classification. The hypotheses put forward so far propose affilia- tions with neighbouring language groups: South Omotic (Ehret p.c.), Nilo- Saharan (Blaŝek 1991, 2001 and forth.), Cushitic (Bender p.c.) and East Cushitic (Sav¿ ߃ Tosco 2003). -

WP-9-Djinang Dictionary

WORK PAPERS OF SIL-AAB Series B Volume 9 AN INTERIM DJINANG DICTIONARY October 1983 WORK PAPERS OF SIL-AAB Series B Volume 9 AN INTERIM DJINANG DICTIONARY Compiled by: Bruce Waters SUMMER INSTITUTE OF LINGUISTICS AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINES BRANCH DARWIN October 1983 i NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA Cataloguing-in-publication Data Waters, Bruce. An interim Djinang dictionary. ISBN 0 86892 270 6. 1. Djinang language - Dictionaries. I. Summer Institute of Linguistics. Australian Aborigines Branch. II. Title. (Series: ¥ork papers of SIL-AAB. Series B; no. 9). 499' .15 ii PREFACE These Work Papers are being produced in two series by the Summer Institute of Linguistics, Australian Aborigines Branch, Inc. in order to make results of SIL research in Australia more widely available. Series A includes technical papers on linguistic or anthropological analysis and description, or on literacy research. Series B contains material suitable for a broader audience, including the lay audience for which it is often designed, such as language learning lessons and dictionaries. Both series include reports on current research and on past research projects. Some papers by other than SIL members are included, although most are by SIL field workers. The majority of material concerns linguistic matters, although related fields such as anthropology and education are also included. Because of the preliminary nature of most of the material to appear in the Work Papers, these volumes are being circulated on a limited basis. It is hoped that their contents will prove of interest to those concerned with linguistics in Australia, and that comment on their contents will be forthcoming from the readers. -

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 29, Number 2, Fall 2000 a SKETCH

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 29, Number 2, Fall 2000 A SKETCH OF ONGOTA A DYING LANGUAGE OF SOUTHWEST ETHIOPIA * Graziano Sava Leiden University, The Netherlands Mauro Tosco Istituto Universitario Orientale, Naples, Italy The article provides a grammatical sketch of Ongota, a language on the brink of extinction (actively used by eight out of an ethnic group of nearly one hundred) spoken in the South Omo Zone of Southwestern Ethiopia. The language has now been largely superseded by Ts'amakko, a neigh boring East Cushitic language, and code-switching in Ts'arnakko occurs extensively in the data. A peculiar characteristic of Ongota is that tense distinctions on the verb are marked only tonally. Ongota's genetic affiliation is uncertain, but most probably Afroasiatic, either Cushitic or Omotic; on the other hand, it must be noted that certain features of the language (such as the almost complete absence of nominal morphology and of inflectional verbal morphology) point to an origin from a creolized pidgin. * We are grateful to the Italian National Research Center (C.N.R.) for funding the research upon which this paper is based. and to the Institute of Ethiopian Studies at Addis Ababa University for granting us the permission to carry on our fieldwork in the area. Previous data on various points of Ongota grammar has been presented jointly by the authors at the "XIVth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies" (Addis Ababa, November 6-11, 2000) and, by Graziano Sava, at the Symposium "Ethiopian Morphosyntax in an Areal Perspective" (Leiden, February 4-5, 2001). We thank all those who. -

Omotic Livestock Terminology and Its Implications for the History of Afroasiatic

Omotic livestock terminology and its implications for the history of Afroasiatic Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm Cambridge, Wednesday, 15 November 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGURES..........................................................................................................................................................I 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 2 2. CAMEL........................................................................................................................................................ 3 3. HORSE......................................................................................................................................................... 3 4. DONKEY ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 5. CATTLE ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 6. GOAT........................................................................................................................................................... 8 7. SHEEP....................................................................................................................................................... -

What's in a Name? a Typological and Phylogenetic

What’s in a Name? A Typological and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Names of Pama-Nyungan Languages Katherine Rosenberg Advisor: Claire Bowern Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract The naming strategies used by Pama-Nyungan languages to refer to themselves show remarkably similar properties across the family. Names with similar mean- ings and constructions pop up across the family, even in languages that are not particularly closely related, such as Pitta Pitta and Mathi Mathi, which both feature reduplication, or Guwa and Kalaw Kawaw Ya which are both based on their respective words for ‘west.’ This variation within a closed set and similar- ity among related languages suggests the development of language names might be phylogenetic, as other aspects of historical linguistics have been shown to be; if this were the case, it would be possible to reconstruct the naming strategies used by the various ancestors of the Pama-Nyungan languages that are currently known. This is somewhat surprising, as names wouldn’t necessarily operate or develop in the same way as other aspects of language; this thesis seeks to de- termine whether it is indeed possible to analyze the names of Pama-Nyungan languages phylogenetically. In order to attempt such an analysis, however, it is necessary to have a principled classification system capable of capturing both the similarities and differences among various names. While people have noted some similarities and tendencies in Pama-Nyungan names before (McConvell 2006; Sutton 1979), no one has addressed this comprehensively. -

A Study Guide by Marguerite Olhara

Big Boss © ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY MArguerite O’HARA http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-170-6 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Murrungga Island is situated in the top end of Arnhem Land in a group of islands known as The Crocodile Islands. This is where we find 95-year-old Laurie Baymarrwangga or as she is affectionately known, ‘Big Boss’, who was named Senior Australian of the Year in 2012. Big Boss is the story of this 95-year-old Indigenous Elder and her challenge as the remaining leader of the Yan-nhangu speaking people to pass on her traditional knowledge to the next generation. We learn about Baymarrwangga’s life story, from her time as a young girl on Murrungga Island to the time she saw the arrival of missionaries, witnessed the arrival of Japanese and European fishermen, and then experienced war and tumultuous change. The story documents a historical legacy of gov- ernment neglect, and suppression of bilingual education and how the language and culture of the Yan-nhangu came to be in a precarious position. The documentary describes Baymarrwangga’s single greatest achievement: the Yan-nhangu Dictionary. The dictionary’s main aim is to preserve Yan-nhangu language and local knowledge from the potentially damaging consequences of rapid global change. Key community people – all related to Big Boss – also feature in the film. Through them, we learn people that have been lost in other Indigenous ‘She knows about the unique lifestyle of the Yan-nhangu– communities. the stories … speaking people: the traditional method of building a bark canoe, constructing a fish trap and the ritual The information and student activities in this guide she’s a very practices of turtle hunting and the daily collection are designed to encourage students to respond to important of turtle eggs.