Identity and Eastern Penan in Borneo1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

Volume 3, No. 1, 1971

PJ'( BORNEO RESEARCHBULLETIN I Vol. 3, No. 1 June, 1971 Notes from the Editor: Special Issues -BRB; Contributions Received ; New Member of Board of Directors. Research Notes Milestones in the History of Kutai, Kalimantan-Timur, Borneo ...........................................J. R. Wortmann 5 New Radio-Carbon [C-14) Dates from Brunei.. .. .Tom Harrisson 7 The Establishment of a Residency in Brunei 1881-1905....,... ..*.~.........................*.......Colin Neil Crisswell 8 Bajau Pottery-making in the Semporna District. ..C. A. Sather 10 Bajau Villages in the Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia....... .....t....+,...l............,~,.,............C. A. Sather 11 James Brooke and British Political Activities in Borneo and Sulu 1839-1868: Local Influences on the Determination of Imperial Policy ............................LE. Ingleson 12 History of Missionary Activity in Borneo: A Bibliographic Note ...........................+.....,..,....a y B. Crain 13 Report on Anthropological Field Work Among the Lun Bawang (Murut) People of Sarawak ..................James L. Deegan 14 Sabah Timber Exports: 1950-1968. ..............LOH Chee-Seng 16 Systems of Land Tenure in Borneo: A Problem in Ecological Determinism ..........................t.....,.G. N. Appell 17 Brief Communications Responsibility in Biolog,ical Field Work........ ............. 20 Developments in Section CT: Conservation--International Biological Programme.. .. .. .. , . 23 An Analysis of Developmental Change Among the Iban.. .. .......................................+...Pet D. Weldon 25 Institute of South-East Asian Biology, University of Aberdeen, Scotland--U.K ................,*...A, G. Marshall 25 Borneo Studies at the University of Hull........M. A. Jaspan 26 Request for Information on Tumbaga, A Gold-Copper Alloy ..... 27 Major Investments by Shell and Weyerhaeuser in Borneo. .. 27 Notes and Comments from -BRB Readers,,....................... 28 The Borneo Research Bulletin is published twice yearly (June and December) by the Borneo Research Council. -

Language Use and Attitudes As Indicators of Subjective Vitality: the Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 190–218 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24973 Revised Version Received: 1 Dec 2020 Language use and attitudes as indicators of subjective vitality: The Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia Su-Hie Ting Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Andyson Tinggang Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Lilly Metom Universiti Teknologi of MARA The study examined the subjective ethnolinguistic vitality of an Iban community in Sarawak, Malaysia based on their language use and attitudes. A survey of 200 respondents in the Song district was conducted. To determine the objective eth- nolinguistic vitality, a structural analysis was performed on their sociolinguistic backgrounds. The results show the Iban language dominates in family, friend- ship, transactions, religious, employment, and education domains. The language use patterns show functional differentiation into the Iban language as the “low language” and Malay as the “high language”. The respondents have positive at- titudes towards the Iban language. The dimensions of language attitudes that are strongly positive are use of the Iban language, Iban identity, and intergenera- tional transmission of the Iban language. The marginally positive dimensions are instrumental use of the Iban language, social status of Iban speakers, and prestige value of the Iban language. Inferential statistical tests show that language atti- tudes are influenced by education level. However, language attitudes and useof the Iban language are not significantly correlated. By viewing language use and attitudes from the perspective of ethnolinguistic vitality, this study has revealed that a numerically dominant group assumed to be safe from language shift has only medium vitality, based on both objective and subjective evaluation. -

SPEAKING IBAN by Burr Baughman Edited by Rev

SPEAKING IBAN by Burr Baughman Edited by Rev. Dr. James T. Reuteler, Ph.D. 2 SPEAKING IBAN TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................... 5 LESSON ONE ..........................................................................................................................7 1. Basic Words and Sentences ...........................................................................................7 2. Note A: Glottal Stop ......................................................................................................9 3. Note B: Position of Modifiers ......................................................................................10 4. Note C: Possessive .......................................................................................................11 5. Exercises ......................................................................................................................11 LESSON TWO ......................................................................................................................15 1. Basic Words and Sentences .........................................................................................15 2. Note A: Sentence Structure ..........................................................................................17 Simple Statement Simple Question 3. Note B: Numeral Classifiers ........................................................................................23 4. Note C: Terms of Address -

The Response of the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol21, No 6, pp 977 – 988, 2000 Globalizationand democratization: the responseo ftheindigenous peoples o f Sarawak SABIHAHOSMAN ABSTRACT Globalizationis amulti-layered anddialectical process involving two consequenttendencies— homogenizing and particularizing— at the same time. Thequestion of howand in whatways these contendingforces operatein Sarawakand in Malaysiaas awholeis therefore crucial in aneffort to capture this dynamic.This article examinesthe impactof globalizationon the democra- tization process andother domestic political activities of the indigenouspeoples (IPs)of Sarawak.It shows howthe democratizationprocess canbe anempower- ingone, thus enablingthe actors to managethe effects ofglobalization in their lives. Thecon ict betweenthe IPsandthe state againstthe depletionof the tropical rainforest is manifested in the form of blockadesand unlawful occu- pationof state landby the former as aform of resistance andprotest. Insome situations the federal andstate governmentshave treated this actionas aserious globalissue betweenthe international NGOsandthe Malaysian/Sarawakgovern- ment.In this case globalizationhas affected boththe nation-state andthe IPs in different ways.Globalization has triggered agreater awareness of self-empow- erment anddemocratization among the IPs. These are importantforces in capturingsome aspects of globalizationat the local level. Globalization is amulti-layered anddialectical process involvingboth homoge- nization andparticularization, ie the rise oflocalism in politics, economics, -

Getting the Malaysian Native Penan Community Do Business for Inclusive Development and Sustainable Livelihood

PROSIDING PERKEM 10, (2015) 434 – 443 ISSN: 2231-962X Getting The Malaysian Native Penan Community Do Business For Inclusive Development And Sustainable Livelihood Doris Padmini Selvaratnam Faculty of Economics and Management, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Email: [email protected] Hamidah Yamat Faculty of Education Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Email: [email protected] Sivapalan Selvadurai Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Email: [email protected] Novel Lyndon Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Email: [email protected] ABRSTRACT The Penan are a minority indigenous community in Sarawak, Malaysia. Traditionally the avatars of highland tropical forests, today they are displaced, in a foreign setting, forced to pick up new trade and skills to survive the demands of national economic advancement. Forced relocation did not promise jobs, but necessity of survival forced them to submit to menial jobs at construction sites and plantations to ensure that food is available for the household. Today, a new model of social entrepreneurship is introduced to the Penan to help access their available skills and resources to encourage the development of business endeavors to ensure inclusive development and sustainable livelihood of the Penan. Interviews and field observation results analysed show that the Penan are not afraid of setting their own markers in the business arena. Further analysis of the situation show that the success of the business is reliant not just on the resilience and hard work of the Penan but also the friendly business environment. Keywords: Native, Penan, Malaysia, Business, Inclusive Development, Sustainable Livelihood THE PENAN’ NEW SETTLEMENT AWAY FROM THE HIGHLAND TROPICAL FOREST The Penan community is indigenous to the broader Dayak group in Sarawak, Malaysia. -

Dewan Negara

Bil. 5 Rabu 2 Mei 2012 MALAYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN DEWAN NEGARA PARLIMEN KEDUA BELAS PENGGAL KELIMA MESYUARAT PERTAMA K A N D U N G A N MENGANGKAT SUMPAH (Halaman 1) PEMASYHURAN TUAN YANG DI-PERTUA Mengalu-alukan Pelantikan Semula Ahli dan Kedatangan Ahli Baru (Halaman 1) JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN LISAN BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 2) USUL-USUL: Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 20) Menjunjung Kasih Titah Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong - YB Tuan Khoo Soo Seang (Halaman 21) Diterbitkan Oleh: CAWANGAN PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN MALAYSIA 2012 DN 2.5.2012 i AHLI-AHLI DEWAN NEGARA 1. Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, Tan Sri Abu Zahar bin Dato’ Nika Ujang 2. Yang Berhormat Timbalan Yang di-Pertua, Puan Doris Sophia ak Brodi 3. “ Dato’ Haji Abdul Rahim bin Haji Abdul Rahman (Dilantik) 4. “ Datuk Haji Abdul Rahman bin Bakar (Dilantik) 5. “ Tuan Haji Abdul Shukor bin P A Mohd Sultan (Perlis) 6. “ Tuan Haji Ahamat @ Ahamad bin Yusop (Johor) 7. “ Tuan Ahmad bin Hussin (Perlis) 8. “ Tuan A. Kohilan Pillay a/l G. Appu (Dilantik) – Senator – Timbalan Menteri Luar Negeri I 9. “ Datuk Dr. Awang Adek Hussin (Dilantik) – Senator – Timbalan Menteri Kewangan I 10. “ Dato’ Azian bin Osman (Perak) 11. “ Tuan Baharudin bin Abu Bakar (Dilantik) 12. “ Dato’ Boon Som a/l Inong (Dilantik) 13. “ Puan Chew Lee Giok (Dilantik) 14. “ Tuan Chiew Lian Keng (Dilantik) 15. “ Datuk Chin Su Phin (Dilantik) 16. “ Datuk Chiw Tiang Chai (Dilantik) 17. “ Puan Hajah Dayang Madinah binti Tun Abang Haji Openg (Sarawak) 18. “ Dato’ Donald Lim Siang Chai (Dilantik) – Senator – Timbalan Menteri Kewangan II 19. -

The Iban Dairies of Monica Freeman 1949-1951. Including Ethnographical Drawings, Sketches, Paintings, Photographs and Letters, Laura P

Moussons Recherche en sciences humaines sur l’Asie du Sud-Est 17 | 2011 Les frontières « mouvantes » de Birmanie The Iban Dairies of Monica Freeman 1949-1951. Including Ethnographical Drawings, Sketches, Paintings, Photographs and Letters, Laura P. Appell- Warren (ed.) Philipps: Borneo Research Council, monographs series n° 11, 2009, XLII + 643 p., glossary, appendix, biblio-graphy, illustrations (maps, figures and color plates) Antonio Guerreiro Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/moussons/642 ISSN: 2262-8363 Publisher Presses Universitaires de Provence Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2011 Number of pages: 178-180 ISBN: 978-2-85399-790-4 ISSN: 1620-3224 Electronic reference Antonio Guerreiro, « The Iban Dairies of Monica Freeman 1949-1951. Including Ethnographical Drawings, Sketches, Paintings, Photographs and Letters, Laura P. Appell-Warren (ed.) », Moussons [Online], 17 | 2011, Online since 25 September 2012, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/moussons/642 Les contenus de la revue Moussons sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 178 Comptes rendus / Reviews The Iban Dairies of Monica Freeman under Leach’s supervision at Cambridge’s 1949-1951. Including ethnographical University Department of Anthropology2. drawings, sketches, paintings, pho- While in the field, at the end of 1949, tographs and letters, Laura P. Appell- Derek Freeman decided to concentrate on his Warren (ed.), Philipps: Borneo Research ethnographical and ethnogical notes while Council, monographs series n° 11, 2009, Monica was to write the ieldwork’s dairies. XLII + 643 p., glossary, appendix, biblio- Although she had no formal training in art, she made beautiful and very detailed ethno- graphy, illustrations (maps, figures and graphic drawings, sketches and paintings. -

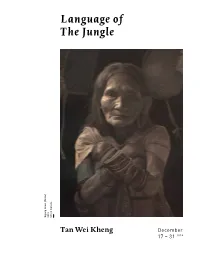

Language of the Jungle

Language of The Jungle Oil on Canvas Sigang Kesei (Detail) Sigang Kesei 2013 Tan Wei Kheng December 17 – 31 2014 Has the jungle become more beautiful? The artist Tan Wei Kheng paints portraits of the unseen heroes of the nomadic Penan tribe in Sarawak, Malaysia. He invites us to discover the values and dreams of the Penans, who continue with their struggles in order to live close to nature. Tan is also involved in other initiatives and often brings with him rudimentary Language Of supplies for the Penans such as rice, sugar, tee shirts, and toothpaste. As natural – Ong Jo-Lene resources are destroyed, they now require supplements from the modern world. The Jungle Kuala Lumpur, 2014 Hunts do not bear bearded wild pigs, barking deers and macaques as often anymore. Now hunting takes a longer time and yields smaller animals. They fear that the depletion of the tajem tree from which they derive poison for their darts. The antidote too is from one specific type of creeper. The particular palm tree that provides leaves for their roofs can no longer be found. Now they resort to buying tarpaulin for roofing, which they have to carry with them every time they move Painting the indigenous peoples of Sarawak is but one aspect of the relationship from camp to camp. Wild sago too is getting scarcer. The Penans have to resort to that self-taught artist, Tan Wei Kheng has forged with the tribal communities. It is a farming or buying, both of which need money that they do not have. -

Adaptation to Climate Change: Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Hold the Key?

sustainability Article Adaptation to Climate Change: Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Hold the Key? Nadzirah Hosen 1,* , Hitoshi Nakamura 2 and Amran Hamzah 3 1 Graduate School of Engineering and Science, Shibaura Institute of Technology, Saitama City, Saitama 337-8570, Japan 2 Department of Planning, Architecture and Environmental Systems, Shibaura Institute of Technology, Saitama City, Saitama 337-8570, Japan; [email protected] 3 Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Built Environment and Surveying, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai 81310, Johor Bahru, Johor, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 December 2019; Accepted: 15 January 2020; Published: 16 January 2020 Abstract: The traditional knowledge of indigenous people is often neglected despite its significance in combating climate change. This study uncovers the potential of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) from the perspective of indigenous communities in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, and explores how TEK helps them to observe and respond to local climate change. Data were collected through interviews and field work observations and analysed using thematic analysis based on the TEK framework. The results indicated that these communities have observed a significant increase in temperature, with uncertain weather and seasons. Consequently, drought and wildfires have had a substantial impact on their livelihoods. However, they have responded to this by managing their customary land and resources to ensure food and resource security, which provides a respectable example of the sustainable management of terrestrial and inland ecosystems. The social networks and institutions of indigenous communities enable collective action which strengthens the reciprocal relationships that they rely on when calamity strikes. -

A Policy Proposal for Heritage Language Conservation: a Case for Indonesia and Sarawak

Issues in Language Studies (Vol. 6 No. 2 – 2017) A POLICY PROPOSAL FOR HERITAGE LANGUAGE CONSERVATION: A CASE FOR INDONESIA AND SARAWAK Bambang SUWARNO Universitas Bengkulu, Indonesia Jalan W. R. Supratman, Bengkulu 38371, Indonesia [email protected] Manuscript received 7 July 2017 Manuscript accepted 4 October 2017 ABSTRACT Heritage languages are declining in Indonesia and Sarawak. They need conservation due to their situations as endemic languages. Their decline could be attributed to the fact that they often do not possess significant roles in the public domains. As a result, their speakers see little rewards or prestige for maintaining them. In Indonesian and Malaysian constitutions there is a spirit for protecting heritage languages. However, their executions, through national laws, might not have provided adequate protection for the heritage languages. As heritage languages keep declining, a policy revision needs to be given consideration. A heritage language may better survive if it has some functions in the public domains. Thus, to conserve the heritage languages, there is a need for the revision of language policy, so that these languages may have roles in the public domains, with varying scope, depending on their size. Large regional languages may be given maximum roles in the public domains, while smaller regional languages may be given smaller roles. Language conservation areas could be developed, where heritage languages serve as co-official languages, besides the national language. These areas may range from a district to a province or a state. Keywords: language policy, language planning, heritage language, language conservation IntroDuction: Why Heritage Languages Must Be Conserved? Before starting the discussion, it is essential to define heritage language. -

Home 12 ● Thesundaypost ● October 19, 2008

home 12 ● thesundaypost ● October 19, 2008 QUIET: The settlement at Long Item where the residents have gone hunting and gathering Govt makes education in the jungle. top priority for Penans ● From Page 1 go there and this is the foreign NGOs for their where they meet new own ends. Office and the agencies people.” Taking a dim view of the concerned on organising Some elders naturally concern expressed by the seminars to create greater disliked the idea of these foreign NGOs on the awareness on the rights of youngsters spending more welfare of his community, Penan and Orang Ulu and more time at the camp, he said the Penans were just women, sexual harassment, he noted. a convenient tool for so- single motherhood and other Asked whether the called environmentalists to women-related issues. community was known to further their cause in the He is also scheduled to practise ‘mengayap’ European Union. meet all the Penan chiefs on (sleeping around), he said: “This is a community Oct 20 and a unanimous “No.” issue which has become an statement calling on the In the old days, John international issue just managements of all timber added, a Penan man because they use Penan as operators and their workers interested in a woman would their capital to lobby against to respect the local cultures invite her to join him on a the Malaysian timber and and traditions is expected READY TO SERVE: John (left) and Dawat helping with HEALTH CARE NEEDED: Penans at Long Kawi waiting for fishing trip so that they plantation sectors,” he said.