Palindromes and Letter Formulae: Some Reconsiderations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VILJANDI RAHVARÕIVAD Tiina Jürgen, Viljandi Muuseumi Teadur

VILJANDI RAHVARÕIVAD Tiina Jürgen, Viljandi Muuseumi teadur Viljandi kihelkond asus Viljandi maakonna südames. Põhja poole jäid Kolga-Jaani, Suure-Jaani, Pilistvere ja Põltsamaa, lõuna poole Paistu ning Tarvastu kihelkond. Läänepiiriks oli Kõpu kihelkond ja idapiiriks Võrtsjärv. Wiljandi on otse nagu Eestlaste südame koht, kirjutas Jaan Jung 1898. aastal (1898, 66). Viljandi kihelkond oli etnograafiliselt üleminekukihelkond, kus rah- varõivaste lõikes ja kaunistustes leidus nii põhjaeestilisi kui ka lõunaees- tilisi jooni. Viljandimaa põhjakihelkonnad olid suhteliselt vastuvõtlikud uuendustele ja moemõjutustele, ühtlasi esines siinses rõivastuses ka ühisjooni Põhja-Eestiga, mis Viljandist kaugemale lõunasse ei ulatunud. Kihelkonna lõunapoolsed alad esindasid aga Lõuna-Viljandimaa etno- graafilisi elemente. Lõunapoolsetes valdades kandsid naised sarnaselt Mulgi kihelkondadele madala püstkrae ja punase ristpistetikandiga sär- ki, tarvastu tanu, punaste nööridega pikk-kuube, punaseid roositud kin- daid ja laia sääremarjaga sukki. Seevastu Viljandist põhja poole jäävates valdades kodunesid Põhja-Eesti mõjutusel pikk-kuue kõrval potisinised villased seesidega kampsunid, rikkaliku valge tikandi ja mahamurtava kraega särgid, väikesed tanud, esiääres niplis- või poepits, ja kahelõnga- lised e sinise-valgekirjalised kindad ning roositud sukad. Ka meeste mood oli Viljandist põhja poole jäävates valdades teistsu- gune kui lõuna pool Viljandit, kus mehed kandsid visalt vanamoelisi idamulgilikke rõivaid. Põhjapoolsetes valdades läksid mehed põhjaees- tilike moemõjutustega kergemini kaasa, võttes tarvitusele potisinisest täisvillasest riidest ülikonna (vrd TAHVEL I, III). Naise ja neiu rõivas (TAHVEL I, II, III) Viljandi naiseülikonda kuulusid 19. sajandi keskel peenest linasest riidest särk, pikitriibuline villane seelik või linane pallapool, linane rüü, kampsun või must villane pikk-kuub, kasukas, põll, vöö, väike tanu, sukad, kindad ja jalanõudena pastlad, hiljem kingad. Viljandi neiu kandis samasuguseid rõivaid, kuid ilma põlle ja tanuta. -

Environment and Settlement Location Choice in Stone Age Estonia

Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 2020, 24, 2, 89–140 https://doi.org/10.3176/arch.2020.2.01 Kaarel Sikk, Aivar Kriiska, Kristiina Johanson, Kristjan Sander and Andres Vindi ENVIRONMENT AND SETTLEMENT LOCATION CHOICE IN STONE AGE ESTONIA The location choice of Stone Age settlements has been long considered to be influenced by environmental conditions. Proximity to water and sandy soils are most typical examples of those conditions. The notion of the influence resulted from the evidence from a relatively small amount of sites. During the recent decades the number of known settlements has increased to a level where statistical assessment of relation between environmental characteristics and settlement location choice is possible. To undertake this task we collected data about known Estonian Stone Age settlements and acquired environmental data of their locations using publicly available geological datasets. We provide univariate descriptive statistics of the distributions of variables describing site conditions and compare them to characteristics generally present in the environment. We experiment with a set of environmental variables including soil type, distance to water and a selection of geomorphometry derivatives of the digital elevation model. Quantitative assessment confirmed previous observations showing a significant effect towards the choice of sandy, dry location close to water bodies. The statistical analysis allowed us to assess the effect size of different characteristics. Proximity to water had the largest effect on settlement choice, while soil type was also of considerable importance. Abstract geomorphological variables such as Topographic Position Index and Topographic Wetness index also inform us about significant effects of surface forms. Differences of settlement locations during stages of the Stone Age are well observable. -

Tarvastu Valla Üldplaneering

TARVASTU VALLA ÜLDPLANEERING TARVASTU VALLA ÜLDPLANEERING Tarvastu-Pärnu 2007 1 TARVASTU VALLA ÜLDPLANEERING SISUKORD SISUKORD ...........................................................................................................................2 EESSÕNA ............................................................................................................................4 1 RUUMILISE ARENGU PÕHIMÕTTED 2010 ..................................................................5 1.1 ASENDIST TULENEVAD ARENGUVÕIMALUSED .................................................................................6 1.2 RAHVASTIK JA ASUSTUSJAOTUS .......................................................................................................7 1.2.1 Asustus ja asulate omavahelised suhted....................................................................................7 1.2.2 Rahvaarvu prognoos...................................................................................................................8 2 MAA- NING VEEALADE RESERVEERIMINE JA MÄÄRAMINE..................................10 2.1 MAA -ALADE RESERVEERIMINE ......................................................................................................10 2.2 MAAKASUTUSE MÄÄRAMINE .........................................................................................................11 2.3 SADAMAD , LAUTRID JA VEE -ALADE RESERVEERIMINE .................................................................12 2.4 ELAMUALAD ....................................................................................................................................14 -

Kolga-Jaani Rahvamaja Avati Vägeva Peoga 30

Nr 11 (35) • November 2020 Ansambel Trad. Attack! pani Kolga-Jaani rahva rõkkama. Fotod: Karen Akopjan Kolga-Jaani rahvamaja avati vägeva peoga 30. oktoobri õhtul avati suu- on oma toimetamistega praegu rejoonelise peoga Kolga-Jaani väga eredalt pildis. Võib isegi Villem Reimani nimeline rah- öelda, et Kolga-Jaani on viimasel vamaja. Rahvale esines ka an- ajal oma kultuuritegevuse poo- sambel Trad. Attack!. lest uhkem kui Viljandi,” märkis Ajaloolise rahvamaja, mille va- vallavavanem. nem osa ehitati kirikuõpetaja ja Annika Jones lubas hoida rah- Eesti rahvusliku liikumise ühe vamaja lippu kõrgel. „Luban, et juhi Villem Reimani eestvõttel sündmused saavad järjest roh- juba 1902. aastal, müüs Viljandi kem hoogu juurde ja järjest põ- vallale Hovard Nurme. Nurme nevamaid asju hakkab siin toi- ostis lagunenud maja 2005. aas- muma. Aga kõige enam tahan tal ja renoveeris selle aastatel ma, et siia majja tuleb taas kord 2006–2007. elu sisse, tekib huvitegevus, siin “Võtsid selle suure rolli en- hakatakse koos käima. Olen dale, nagu omal ajal ka Villem väga õnnelik selle võimaluse Reiman, kes leidis, et ühte sel- üle ja et minu ümber on selline list hoonet on kohalikule kogu- mõnus kogukond,” rääkis Jones. konnale vaja,” tänas avamisel Rahvamaja avamispeol anti Hovard Nurmet Viljandi valla- üle ka autasud Kolga-Jaani bus- vanem Alar Karu. siootepaviljoni ideekonkursi “Arvan, et see maja saab uue võitnud Tallinna Tehnikakõrg- elamise. Siia tuleb raamatu- kooli arhitektuuritudengitele ja kogu ja kui rahvas soovib, ka tänati kohalikke, kes andsid olu- muuseum,” lisas Karu ja andis lise panuse maal elamise päeva rahvamaja lipu üle Kolga-Jaani korraldamisse. kultuuritöötajale Annika Jone- Kolga-Jaani kultuuritöötaja Annika Jones, Viljandi vallavanem Alar Karu, volikogu esimees Kaupo Kase ja rahvamaja sile, kes juhib kohalikku kultuu- Made Laas, endine omanik Hovard Nurme. -

Tarvastu Valla Noorsootöö Kvaliteet

TARTU ÜLIKOOLI VILJANDI KULTUURIAKADEEMIA Kultuurhariduse osakond Huvijuht-loovtegevuse õpetaja õppekava Liis Lääts TARVASTU VALLA NOORSOOTÖÖ KVALITEET Lõputöö Juhendaja: Lii Araste, MA, kogukonnatöö lektor Kaitsmisele lubatud: ……….……………… (juhendaja allkiri) Viljandi 2016 SISUKORD SISSEJUHATUS ............................................................................................................................ 4 1. NOORSOOTÖÖ SUUNAD ...................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Noorsootöö piirid .................................................................................................................. 6 1.1.1. Euroopas ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.2. Eestis ............................................................................................................................ 10 1.1.3. Kohalikus omavalitsuses .............................................................................................. 13 1.1.3.1. Tarvastu vallas ....................................................................................................... 15 1.2. Noorsootöö kvaliteet ........................................................................................................... 17 1.2.1 Noorsootöö kvaliteedi hindamine ................................................................................. 18 1.2.1.1. Terviklik kvaliteedi juhtimine ehk TQM.............................................................. -

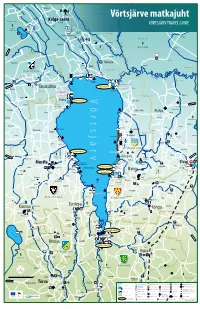

V Õ R T S J Ä R V

Vissuvere P õ l t s a m a a r a b a V.Reiman Võrtsjärve matkajuht Oorgu P a r i k a r a b a Kolga-Jaani Utsali Eesnurga P õ l ts a m a a j õ g i VÕRTSJÄRVSiniküla TRAVEL GUIDE Parika Kaubi Parika sookaitseala Ristivälja Suurkivi Odiste T o r n i r a b a Parika Kolga-Jaani vald järv Laeva T o i r a b a L a e v a s o o Lalsi Ahuoja rahn Laashoone P e d j a j õ g i Kaavere Potaste Lätkalu Alam-Pedja lka Valmaotsa Kivisaare kaitseala Viljandi Oja kaitseala Taressaare Londoni P e d e j õ g I Ristsaare Metsaküla Meleski A.Annist Palupõhja Leie K a r i s t o s o o Tänassilma jõgi M e l e s k i r a b a i V i i r a t s i v a l d jõg ma Ulge Veldemani puhkemaja r E Jõeküla uu Kõrgemäe turismitalu Vaibla puhkekeskus S Su ur Em Oiu ajõg Tusti J.Tõnisson i Reku K a v i l d a j õ g i S o o v a s o o Viiralti tamm Vaibla Võrtsjärve Külastuskeskus Viljandi i Jõeoru villa JÕESUU PUHKEALA Tänassilma Jõesuu turismitalu E l v a j õ g i Uusna Verevi Vanavälja soo Vanasauna puhkemaja Jõesuu Järveveere puhkekeskus Peerna turismitalu Päikesekivi turismitalu Rämsi Valma puhkelaager S a n g l a s o o H.Koppel V õ r t s j ä r v Valma VALMA PUHKEALA Suure-Rakke i Vasara Tartu Mikumärdi soo K a v i l d a ü r g o r g Saba Ruudiküla Väike-Rakke Mõisanurme Riuma Ubesoo jõgi Puhja Mäeselja Kariküla Sangla Kibeküla Järvaküla Järveküla Keeri-Karijärve lka Uniküla Karijärve Mustapali Mäeotsa Saviküla Kobilu Kalevipoja kivi Neemisküla Mõnnaste Kapsta Väluste R a n n u s o o Luiga Kaarlijärve Külaaseme Tamme paljand Vahessaare Maiorg Kalbuse Annikoru Poole Villa Arupera soo -

Context-Related Melodies in Oral Culture 37 Folk Song in Its Primary Function, I.E

COnteXT-RelAteD melODies in OR AL CU LT URE: An AttemPT TO DescR I BE WORDS -AND-music RelAtiOnsHIPS in LOCAL sinGinG TRADitiOns TAIVE SÄRG PhD, Senior Researcher Department of Ethnomusicology Estonian Literary Museum Vanemuise 42, 51003 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In oral folk song traditions we often find many lyrics, but not nearly as many mel- odies. The terms “polyfunctionalism”, “group melodies” or “general melodies” have been used by Estonian researches to indicate the phenomenon that many lyrics were sung to only one, or a small handful, of tunes. The scarcity of melo- dies is supposed to be one of several related phenomena characteristic to an oral, text-centred singing culture. In this article the Estonian folk song tradition will be analysed against a quantity of melodies and their usage in the following aspects: word-and-melody relationships and context-and-melody relationships in Karksi parish (south Estonia); a singer; and native musical terms and the process of sing- ing and (re)creation. KEYWORDS: ethnomusicology ● regilaul ● formula melody ● folk song improvisa- tion ● folk singer IntRODuctiON In this article an attempt will be made to describe and analyse certain aspects of oral singing culture, which appear at first as the abundance of lyrics and scarcity of melo- dies, causing the same melodies to be sung with many texts. Researchers point this out using various terms. The use of limited musical material characterises (at least partially) several traditional song cultures which are quite different according to their location and music style, e.g. Balto-Finnic, Finno-Ugric and Scandinavian peoples, Central- and East-Asian peoples, and also Western folk music and church music, etc. -

Tarvastus Pandi Olümpiasangar Martin Klein Kätel Käima Etsembrikuu 19

Nr 1 2018 · lk 3 • · lk 4 • · lk 5 • · lk 8 Lumekoristus erateedel Ene Saare uus amet Ramsi lasteaed Taruke 50 Vana foto Jaanuar Tarvastus pandi olümpiasangar Martin Klein kätel käima etsembrikuu 19. päeval oli Martin oli teiste hulgas osavaim, Tarvastu inimeste jaoks leeripäeval läks ta Tarvastu kiri- Dkauaoodatud võimalus ku kellatorni kätel. Suur spordi- tunnustada 105 aastat tagasi huvi viis ta lõpuks Stockholmi Eestile esimese olümpiamedali olümpiamängudele, kus Eesti toonud maadlejat Martin Kleini. esimene olümpiamedal tuli Mustla bussijaama esisel Kleini Guinnessi rekordite raamatus- platsil eemaldasid olümpiasan- se kantud 11 tundi ja 40 minutit gar Martin Kleini lapselaps Mar- väldanud maratonmaadlusest. tin Klein, Viljandi vallavanem Martin Kleini tähtsusest ja tä- Alar Karu, skulptuuri autor Mati hendusest Eesti olümpiaajaloos Karmin ja Viljandi Maadlusklubi ning noorte maadluse hetkeolu- Tulevik president Valdeko Kal- korrast rääkisid Eesti Maadlusve- ma katte Tarvastust pärit Eesti teranide Ühenduse esindaja Loit esimese olümpiamedalivõitja Part ja Viljandi Maadlusklubi Tu- Martin Kleini auks valminud levik president Valdeko Kalma. pronksskulptuurilt “Poiss kätel“. Spordi tähenduse kohta on Skulptor Mati Karmin sai olümpiasangar ise lausunud skulptuuri idee Martin Kleini järgmised sõnad: “Mis on sport? kaasaegsete mälestustest, mille See on tervis, jõud ja ilu. Kui ini- põhjal olid Kleini poisid kõik mene on tugev ja terve, siis on ta kõvad hundiratast viskama, hei- ka õnnelik ja rõõmus.“ naküünis turnima ja kätel käi- Maive Feldmann, ma. Karja järel kätel käimine oli Viljandi valla haridus- ja külas ikka tugevate poiste trikk. kultuurinõunik KOMMENTAARID ternaatkoolis maadluse eriala. Martin Klein, Olen mitu korda oma vanaisa olümpia- mälestusvõistlustel medali kaela sangar saanud. See oli uhke tunne. Martin Kleini See on väga ilus kuju, tore on lapselaps näha oma vanaisa poisina kätel kõndimas. -

The Relativity of Time in Estonian Fairy Tales

A MORTAL VISITS THE OTHER WORLD – THE RELATIVITY OF TIME IN ESTONIAN FAIRY TALES MAIRI KAASIK Project Assistant, MA Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore Institute for Cultural Research and Fine Arts University of Tartu Ülikooli 18, 50090 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article* analyses Estonian fairy tales with regard to perceiving supernatural lapses of time, focusing on the tale type cluster A Mortal Visits the Other World, which includes tale types ATU 470, 470A, 471, and 471A. In these tales the mortal finding himself in the world of the dead, heaven or fairyland experiences the accel- erated passage of time. Returning to the mundane temporal reality and learning the truth the hero generally dies. The difference in time perception has been caused by the hero’s movement in space and between spaces. Three vertical spheres can be detected: 1) the upper world (heaven, paradise); 2) the human world; 3) the netherworld (the world of the dead, hell). Usually, the events of a particular tale take place only in the human world, and either in the upper or the netherworld. The relativity of the passing of time on earth and in the other world makes the tales ‘behave’ in a peculiar manner as regards genre, bringing to prominence features of representation of time typical of legends or religious tales. Although the tales contain several features that make them close to legends (a concrete place and personal names, the topic of death, dystopic endings, characters belonging to the reality of legends, etc.), based on Estonian material they can be regarded as part of fairy tales. -

African Swine Fever in Estonia

African swine fever in Estonia PAFF Committee 6.10.2014 Chronology (1) • First case of wild boar: – On 2nd September one wild boar piglet was found dead in Valga distric, Hummuli parish, 6 km from the Latvian border – Autopsy showed clinical signs – Samples taken: spleen, tonsils, kidneys – Preliminary results from National Reference Laboratory (RT-PCR, ELISA) – On 5th September confirmation from EU reference laboratory for African swine fever: • RT-PCR positive, IPT positive • ASFV belongs to genotype II • Possible source of infection: movement of infected wild board from infected area (Latvia) Chronology (2) First case - location Chronology (3) • Second case: – On 7th of September one dead wild boar was found in Viljandi district, Tarvastu parish, 25 km from the first wild boar location – Confirmation from NRL on 9th of September Chronology (4) • 3rd case: – On 15th of September dead wild boar was found in Ida-Virumaa district, Lüganuse parish, 220 km from the second wild boar case location – Source of infection: unknown, possible human interaction Chronology (4) • Map with locations of 3 cases Chronology (5) • 4th case: – On 18th of September one abnormally behaved wild boar was shot in Valgamaa district, Õru parish, 18 km from the first wild boar location – Autopsy: splenomegaly, petechial haemorrhages on kidneys Chronology (6) • Map with locations of 4 cases Chronology – positive cases Week, 2014 Cases in wild boar Location 01/09-07/09 1 Case no 1 (Valga county) 08/09-14/09 4 Case no 2 (Viljandi county) 1 Case no 1 15/09-21/09 1 -

Eesti Mõisakalmistud

Tartu Ülikool Usuteaduskond Võrdleva usuteaduse õppetool Ketlin Sirge Eesti mõisakalmistud Magistritöö Teaduslikud juhendajad: Tarmo Kulmar, dr theol, professor Taavi Pae, PhD Tartu 2013 SISUKORD Sissejuhatus 3 1. Kalmistud Eestis 18.-20. sajandil 13 2. Mõisakalmistute rajamise põhjused 19 2.1 Mõisakultuur 19 2.2 Matmiskombestik 22 2.3 Seadusandlus 23 2.4 Kalmistu tähendus 25 2.5 Järeldused 27 3. Mõisakalmistute iseloomustus 29 3.1 Hulk 29 3.2 Paiknemine 32 3.3 Rajamise aeg 34 3.4 Asukoht 36 3.5 Juurdepääs 38 3.6 Üldiseloomustus 40 3.7 Mõisakalmistutele maetud 43 3.8 Kombestik 45 3.9 Kokkuvõte 46 4. Mõisakalmistud 20.-21. sajandil 48 4.1 Muutused 20. sajandil 48 4.2 Mõisakalmistud taasiseseisvunud Eestis 52 4.3 Mõisakalmistute tulevikust 54 4.4 Kokkuvõte 55 5. Mõisakalmistute andmebaas 56 Kokkuvõte 83 Kasutatud allikad ja kirjandus 86 Summary: The manor cemeteries of Estonia 103 Lisad 106 2 Sissejuhatus Teema valiku põhjendamine Käesolev magistritöö käsitleb Eesti mõisakalmistuid. Mõisakalmistu on väike mõisa maa-alal paiknev erakalmistu, kuhu on maetud mõisniku perekonnaliikmed ja lähisugulased. Seda fenomeni on Eesti kultuuri- ja kirikuloos uuritud väga vähe. Eesti mõisate perekonnakalmistute juurde jõudsin huvist Eesti ajaloo, kalmistute ja mõisaturismi vastu. Turismivaldkonnas jäävad mõisnike perekonnakalmistud oma vähese atraktiivsuse või halva ligipääsetavuse tõttu sageli tähelepanuta. Mõisa või piirkonda tutvustavates raamatutes ja infobrošüürides peatutakse neil pikemalt harva, tavaliselt neid ei mainitagi. Mõisakompleksi juurde püstitatud infotahvlitel mõnikord küll kirjeldatakse erilise kalmistu olemasolu, kuid kuna puuduvad asupaika näitavad kaardid on neid väga keeruline üles leida. Mõisasüdamest enamasti mõnesaja meetri kaugusel asuvate endiste mõisnike kalmistute juurde viitavad harva teeviidad ning sageli on halbade teeolude tõttu juurdepääs neile raskendatud. -

Innovation South Estonia

Sustainable Tartu Visitors Centre Raekoja plats 1A (Town Hall Square), Tar tu Solutions +372 744 2111 [email protected] www.visittartu.com www.visitsouthestonia.com Jõgevamaa Tourist Information Centre and Innovation Suur St. 3, Jõgeva +372 776 8520 [email protected] www.visitjogeva.com In natural building, the energy sphere, creative Võrumaa Tourist Information Centre industry – everywhere where creative ideas, Jüri St. 12, Võru technological knowledge, professional know-how and +372 782 1881 modern technology can be joined, one can feel the [email protected] taste of innovation. www.visitvoru.ee An innovative chicken coop. Põlvamaa Tourist Information Centre The ve chicken living here At least this is how it is in South Estonia where there Kooli St. 1, Räpina, Räpina rural probably don't know that the The joy of self-activity of people who took part in trainings and communal workdays can be seen Chips are ying. A bagpipe maker from the younger generation, On the forefront of product development. Mistress of the Nopri dairy, municipality, Põlva County solar panels (2.8 kW) placed are many clever entrepreneurs who have managed in the summer kitchen in Tuderna, which was made using different clay techniques under Andrus Taul, working very hard at Torupillitalu. July 2014, Valga County. Vilve Niilo, trying out a new product, goat cheese. July 2014, Võru County. +372 799 5001 on their roof provide the watchful eye of natural builder Jaanus Viese. July 2014, Põlva County. [email protected] electricity for their master's to join the old and new to contribute into offering www.visitpolva.ee 50 m² clay house all year more sustainable products and services as well as Wood and Handicraft LÄÄNE- VIRU IDA- VIRU www.visitsetomaa.ee round.