Cobain Article by Chris Leadbeater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home

WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER A) Identification Historic Name: Cobain, Donald & Wendy, House Common Name: Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home Address: 1210 E. First Street City: Aberdeen County: Grays Harbor B) Site Access (describe site access, restrictions, etc.) The nominated home is located mid block near the NW corner of E 1st Street and Chicago Avenue in Aberdeen. The home faces southeast one block from the Wishkah River adjacent to an alleyway. C) Property owner(s), Address and Zip Name: Side One LLC. Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City: Ocean Shores State: WA Zip: 98569 D) Legal boundary description and boundary justification Tax No./Parcel: 015000701700 - 11 - Residential - Single Family Boundary Justification: FRANCES LOT 17 BLK 7 / MAP 1709-04 FORM PREPARED BY Name: Lee & Danielle Bacon Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City / State / Zip: Ocean Shores, WA 98569 Phone: 425.283.2533 Email: [email protected] Nomination June 2021 Date: 1 WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER E) Category of Property (Choose One) building structure (irrigation system, bridge, etc.) district object (statue, grave marker, vessel, etc.) cemetery/burial site historic site (site of an important event) archaeological site traditional cultural property (spiritual or creation site, etc.) cultural landscape (habitation, agricultural, industrial, recreational, etc.) F) Area of Significance – Check as many as apply The property belongs to the early settlement, commercial development, or original native occupation of a community or region. The property is directly connected to a movement, organization, institution, religion, or club which served as a focal point for a community or group. -

A Case Study of Kurt Donald Cobain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) A CASE STUDY OF KURT DONALD COBAIN By Candice Belinda Pieterse Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University December 2009 Supervisor: Prof. J.G. Howcroft Co-Supervisor: Dr. L. Stroud i DECLARATION BY THE STUDENT I, Candice Belinda Pieterse, Student Number 204009308, for the qualification Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology, hereby declares that: In accordance with the Rule G4.6.3, the above-mentioned treatise is my own work and has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. Signature: …………………………………. Date: …………………………………. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several individuals that I would like to acknowledge and thank for all their support, encouragement and guidance whilst completing the study: Professor Howcroft and Doctor Stroud, as supervisors of the study, for all their help, guidance and support. As I was in Bloemfontein, they were still available to meet all my needs and concerns, and contribute to the quality of the study. My parents and Michelle Wilmot for all their support, encouragement and financial help, allowing me to further my academic career and allowing me to meet all my needs regarding the completion of the study. The participants and friends who were willing to take time out of their schedules and contribute to the nature of this study. Konesh Pillay, my friend and colleague, for her continuous support and liaison regarding the completion of this study. -

A Denial the Death of Kurt Cobain the Seattle Police Department

A Denial The Death of Kurt Cobain The Seattle Police Department Substandard Investigation & The Repercussions to Justice by Bree Donovan A Capstone Submitted to The Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University, New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies Under the direction of Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo and approved by _________________________________ Capstone Director _________________________________ Program Director Camden, New Jersey, December 2014 i Abstract Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) musician, artist songwriter, and founder of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band, Nirvana, was dubbed, “the voice of a generation”; a moniker he wore like his faded cardigan sweater, but with more than some distain. Cobain‟s journey to the top of the Billboard charts was much more Dickensian than many of the generations of fans may realize. During his all too short life, Cobain struggled with physical illness, poverty, undiagnosed depression, a broken family, and the crippling isolation and loneliness brought on by drug addiction. Cobain may have shunned the idea of fame and fortune but like many struggling young musicians (who would become his peers) coming up in the blue collar, working class suburbs of Aberdeen and Tacoma Washington State, being on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine wasn‟t a nightmare image. Cobain, with his unkempt blond hair, polarizing blue eyes, and fragile appearance is a modern-punk-rock Jesus; a model example of the modern-day hero. The musician- a reluctant hero at best, but one who took a dark, frightening journey into another realm, to emerge stronger, clearer headed and changing the trajectory of his life. -

Nirvana in Utero Album Download

nirvana in utero album download Nirvana – In Utero (1993) This 20th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition of the unwitting swansong of the single most influential band of the 1990s features more than 70 remastered, remixed, rare and unreleased recordings, including B-sides, compilation tracks, never-before-heard demos and live material featuring the final touring lineup of Cobain, Novoselic, Grohl, and Pat Smear. Additional Info: • Released Date: September 24, 2013 • More Info Hi-Res. Disc 1: Original Album Remastered 01. Serve The Servants (Album Version) – 03:37 02. Scentless Apprentice (Album Version) – 03:48 03. Heart-Shaped Box (Album Version) – 04:41 04. Rape Me (Album Version) – 02:50 05. Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge On Seattle (Album Version) – 04:10 06. Dumb (Album Version) – 02:32 07. Very Ape (Album Version) – 01:56 08. Milk It (Album Version) – 03:55 09. Pennyroyal Tea (Album Version) – 03:39 10. Radio Friendly Unit Shifter (Album Version) – 04:52 11. Tourette’s (Album Version) – 01:35 12. All Apologies (Album Version) – 03:56 B-Sides & Bonus Tracks 13. Gallons Of Rubbing Alcohol Flow Through The Strip (Album Version) – 07:34 14. Marigold (B-Side) – 02:34 15. Moist Vagina (2013 Mix) – 03:34 16. Sappy (2013 Mix) – 03:26 17. I Hate Myself And Want To Die (2013 Mix) – 03:00 18. Pennyroyal Tea (Scott Litt Mix) – 03:36 19. Heart Shaped Box (Original Steve Albini 1993 Mix) – 04:42 20. All Apologies (Original Steve Albini 1993 Mix) – 03:52. Disc 2: Original Album 2013 Mix 01. Serve The Servants (2013 Mix) – 03:38 02. -

{FREE} Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck Ebook

KURT COBAIN: MONTAGE OF HECK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brett Morgen | 160 pages | 05 May 2015 | Insight Editions, Div of Palace Publishing Group, LP | 9781608875498 | English | San Rafael, United States Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck - Wikipedia I loved reading Montage of Heck. Aug 04, Farahdiba Khan rated it it was amazing. I have never watched Montage of Heck. It doesn't seems to be available in my country I live in India btw I am happy to read the interviews from Kurt Cobain's family his dad, mom, step-mom and sister , Krist, Tracy and even Courtney. I think these people too are confused about his death. They seem to try to interpret him from their own perceptions. Anyway, I'll be reading more books later. Need to read Tom Grant's book too. I've absolutely adored Kurt Cobain and his life since the literal moment I was born thanks Dad so I have no idea why it took me so long to get around to this. There are so many aspects of Kurt's life which so many people don't know about and having this compilation of his journals and art "All artists are, in a sense, writing their own biographies with their work. There are so many aspects of Kurt's life which so many people don't know about and having this compilation of his journals and art pieces just really summed him up as a person. May 05, Liliana rated it it was amazing. So I've watched the movie and I've read the book. -

Contradictionary Lies: a Play Not About Kurt Cobain Katie

CONTRADICTIONARY LIES: A PLAY NOT ABOUT KURT COBAIN KATIE WALLACE Bachelor of Arts in English/Dramatic Arts Cleveland State University May 2012 Master of Arts in English Cleveland State University May 2015 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN CREATIVE WRITING at the NORTHEAST OHIO MFA and CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 We hereby approve this thesis For KATIE WALLACE Candidate for the MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN CREATIVE WRITING degree For the department of English, the Northeast Ohio MFA Program And CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by ________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Imad Rahman ____________________________________________________ Department and date _________________________________________________________________ Eric Wasserman _____________________________________________________ Department and date ________________________________________________________________ Michael Geither ____________________________________________________ Department and date Student’s date of defense April 19, 2018 CONTRADICTIONARY LIES: A PLAY NOT ABOUT KURT COBAIN KATIE WALLACE ABSTRACT Contradictionary Lies: A Play Not About Kurt Cobain is a one-act play that follows failed rocker Jimbo as he deals with aging, his divorce, and disappointment. As he and his estranged wife Kelly divvy up their belongings and ultimately their memories, Jimbo is visited by his guardian angel, the ghost of dead rock star Kurt Cobain. Part dark comedy, -

ACR Manual on Contrast Media

ACR Manual On Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media Preface 2 ACR Manual on Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media © Copyright 2021 American College of Radiology ISBN: 978-1-55903-012-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page 1. Preface 1 2. Version History 2 3. Introduction 4 4. Patient Selection and Preparation Strategies Before Contrast 5 Medium Administration 5. Fasting Prior to Intravascular Contrast Media Administration 14 6. Safe Injection of Contrast Media 15 7. Extravasation of Contrast Media 18 8. Allergic-Like And Physiologic Reactions to Intravascular 22 Iodinated Contrast Media 9. Contrast Media Warming 29 10. Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury and Contrast 33 Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Adults 11. Metformin 45 12. Contrast Media in Children 48 13. Gastrointestinal (GI) Contrast Media in Adults: Indications and 57 Guidelines 14. ACR–ASNR Position Statement On the Use of Gadolinium 78 Contrast Agents 15. Adverse Reactions To Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media 79 16. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) 83 17. Ultrasound Contrast Media 92 18. Treatment of Contrast Reactions 95 19. Administration of Contrast Media to Pregnant or Potentially 97 Pregnant Patients 20. Administration of Contrast Media to Women Who are Breast- 101 Feeding Table 1 – Categories Of Acute Reactions 103 Table 2 – Treatment Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 105 Children Table 3 – Management Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 114 Adults Table 4 – Equipment For Contrast Reaction Kits In Radiology 122 Appendix A – Contrast Media Specifications 124 PREFACE This edition of the ACR Manual on Contrast Media replaces all earlier editions. -

Nirvana W Latach 80

seria Z WEHIKUŁEM, tom I: 80s AGAIN! MONOGRAFIA POŚWIĘCONA LATOM 80. XX WIEKU redakcja: Aneta Jabłońska i Mariusz Koryciński Pewne prawa zastrzeżone | Klub Filmowy im. Jolanty Słobodzian | Warszawa 2017 ISBN (wersja elektroniczna): 978-83-64111-79-2 ISBN (wersja drukowana): 978-83-64111-75-4 ABSTRAKT | Paweł Jaskulski w artykule Początki nicości. Nirvana w latach 80. opisuje mniej znany okres istnienia Nirvany. Wprowadzając w tematykę, zastanawia się nad recepcją muzyki rockowej, postrzeganej przez niektórych jako gorszy rodzaj sztuki; przedstawia także narodziny grunge’u – nurtu, który powstał w Stanach Zjednoczonych właśnie w latach 80. XX wieku. Zarysowuje również historię pierwszych – przygotowywanych w chałupniczych warunkach – sesji nagraniowych; genezę debiutanckiej płyty oraz ulubione piosenki Kurta Cobaina. Jaskulski analizuje następnie dokonania Cobaina i Krisa Novoselica z tamtej dekady, wyróżniając następujące obszary refleksji: strategię związaną z nazewnictwem utworów zespołu, sposób kontaktu zespołu z jego odbiorcami oraz autokreację lidera grupy. Pojawia się także wątek płyty Nevermind, pochodzącej wprawdzie z 1991 roku, stanowiącej jednak podsumowanie działalności zespołu z poprzedniej dekady. Paweł Jaskulski [email protected] doktorant na Wydziale Polonistyki Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, gdzie prowadzi zajęcia o kinie. Współredaktor interaktywnego tomu Różne oblicza edukacji audiowizualnej. Autor rozdziałów w monografiach Kultura rocka. Twórcy-tematy-motywy (2); NieZwykłe inspiracje spoza kadru oraz Różne oblicza edukacji audiowizualnej. Publikował na łamach m.in. „Twórczości”, „Odry”, „Nowego Folderu” oraz portali historia.org.pl i publica.pl. Współorganizator konferencji ogólnopolskich („O poprawie polskiego kina”) i międzynarodowych („Edukacja audiowizualna i medialna w Polsce i świecie”); współrealizator kursu „Jak przygotować projekt filmu dokumentalnego?”. Należy do Polskiego Towarzystwa Badań nad Filmem i Mediami. Klub Filmowy im. Jolanty Słobodzian powstał, aby upamiętnić polską reżyserkę i niestrudzoną edukatorkę filmową. -

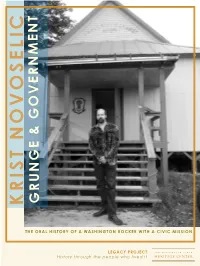

Krist Novoselic

OVERNMENT G & E GRUNG KRIST NOVOSELIC THE ORAL HISTORY OF A WASHINGTON ROCKER WITH A CIVIC MISSION LEGACY PROJECT History through the people who lived it Krist Novoselic Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes October 14, 2008 John Hughes: This is October 14, 2008. I’m John Hughes, Chief Oral Historian for the Washington State Legacy Project, with the Offi ce of the Secretary of State. We’re in Deep River, Wash., at the home of Krist Novoselic, a 1984 graduate of Aberdeen High School; a founding member of the band Nirvana with his good friend Kurt Cobain; politi cal acti vist, chairman of the Wahkiakum County Democrati c Party, author, fi lmmaker, photographer, blogger, part-ti me radio host, While doing reseach at the State Archives in 2005, Novoselic volunteer disc jockey, worthy master of the Grays points to Grays River in Wahkiakum County, where he lives. Courtesy Washington State Archives River Grange, gentleman farmer, private pilot, former commercial painter, ex-fast food worker, proud son of Croati a, and an amateur Volkswagen mechanic. Does that prett y well cover it, Krist? Novoselic: And chairman of FairVote to change our democracy. Hughes: You know if you ever decide to run for politi cal offi ce, your life is prett y much an open book. And half of it’s on YouTube, like when you tried for the Guinness Book of World Records bass toss on stage with Nirvana and it hits you on the head, and then Kurt (Cobain) kicked you in the butt . -

Final Detailed Review Paper on In

FINAL DETAILED REVIEW PAPER ON IN UTERO/LACTATIONAL PROTOCOL EPA Contract Number 68-W-01-023 Work Assignments 1-8 and 2-8 July 14, 2005 Prepared For: Gary E. Timm Work Assignment Manager U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program Washington, DC By: Battelle 505 King Avenue Columbus, OH 43201 AUTHORS Rochelle W. Tyl, Ph.D., DABT Julia D. George, Ph.D. Research Triangle Institute Research Triangle Park, North Carolina TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Abbreviations .................................................................. iv 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................ 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 2 2.1 Developing and Implementing the Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program ......... 2 2.2 The Validation Process .................................................. 3 2.3 Purpose of the DRP ..................................................... 5 2.4 Objective of the in Utero/lactational Protocol Within the EDSP .................... 5 2.5 Methodology Used in this Analysis .......................................... 6 2.6 Definitions ............................................................. 7 3.0 SCIRNTIFIC BASIS OF THE IN UTERO/LACTATIONAL PROTOCOL .................... 8 3.1 Background ........................................................... 8 3.2 Sexual Developm ent in Mam mals ......................................... 11 3.2.1 Both Sexes .................................................... 13 3.2.2 Males ........................................................ -

Krist Novoselic, Dave Grohl, and Kurt Cobain

f Krist Novoselic, Dave Grohl, and Kurt Cobain (from top) N irvana By David Fricke The Seattle band led and defined the early-nineties alternative-rock uprising, unleashing a generation s pent-up energy and changing the sound and future of rock. THIS IS WHAT NIRVANA SINGER-GUITARIST KURT Cobain thought of institutional honors in rock & roll: When his band was photographed for the cover of Rolling Stone for the first time, in early 1992, he arrived wearing a white T-shirt on which he’d written, c o r p o r a t e m a g a z i n e s s t i l l s u c k in black marker. The slogan was his twist on one coined by the punk-rock label SST: “Corporate Rock Still Sucks.” The hastily arranged photo session, held by the side of a road during a manic tour of Australia, was later recalled by photogra pher Mark Seliger: “I said to Kurt, T think that’s a great shirt... but let’s shoot a couple with and without it.’ Kurt said, ‘No, I’m not going to take my shirt off.’” Rolling Stone ran his Fuck You un-retouched. ^ Cobain was also mocking his own success. At that moment, Nirvana - Cobain, bassist Krist Novoselic, and drummer Dave Grohl - was rock’s biggest new rock band, propelled out of a long-simmering postpunk scene in Seattle by its incendiary second album, N everm ind, and an improbable Top Ten single, “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Right after New Year’s Day 1992, Nevermind - Nirvana’s first major-label release and a perfect monster of feral-punk challenge and classic-rock magne tism, issued to underground ecstacy just months before - had shoved Michael Jackson’s D angerous out of the Number One spot in B illboard.