Climate Change and Human Security from a Northern Point of View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM and MYSTICISM in AMERICAN NATURE WRITING by DAVID TAGNANI a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfill

ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM AND MYSTICISM IN AMERICAN NATURE WRITING By DAVID TAGNANI A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of English MAY 2015 © Copyright by DAVID TAGNANI, 2015 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by DAVID TAGNANI, 2015 All Rights Reserved ii To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of DAVID TAGNANI find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________________ Christopher Arigo, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________________ Donna Campbell, Ph.D. ___________________________________________ Jon Hegglund, Ph.D. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my committee members for their hard work guiding and encouraging this project. Chris Arigo’s passion for the subject and familiarity with arcane source material were invaluable in pushing me forward. Donna Campbell’s challenging questions and encyclopedic knowledge helped shore up weak points throughout. Jon Hegglund has my gratitude for agreeing to join this committee at the last minute. Former committee member Augusta Rohrbach also deserves acknowledgement, as her hard work led to significant restructuring and important theoretical insights. Finally, this project would have been impossible without my wife Angela, who worked hard to ensure I had the time and space to complete this project. iv ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM AND MYSTICISM IN AMERICAN NATURE WRITING Abstract by David Tagnani, Ph.D. Washington State University May 2015 Chair: Christopher Arigo This dissertation investigates the ways in which a theory of material mysticism can help us understand and synthesize two important trends in the American nature writing—mysticism and materialism. -

Bulloch Times (Statesboro News-Statesboro Eagle)

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Bulloch County Newspapers (Single Issues) Bulloch County Historical Newspapers 2-14-1929 Bulloch Times (Statesboro News-Statesboro Eagle) Notes Condition varies. Some pages missing or in poor condition. Originals provided for filming by the publisher. Gift of tS atesboro Herald and the Bulloch County Historical Society. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/bulloch-news- issues Recommended Citation "Bulloch Times (Statesboro News-Statesboro Eagle)" (1929). Bulloch County Newspapers (Single Issues). 1407. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/bulloch-news-issues/1407 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Bulloch County Historical Newspapers at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulloch County Newspapers (Single Issues) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THURSDAY, FEB BULLOCH 'UMES AND SrATESBO.RO NEWS �� !!"'tIetHriwa'H,....,� ,--=--_:_--....J"--------------------� �trs C Z Donaldson and children I COME TO .. ,I .. 'f ... Social Happenings for the Week I :��:,t �:stan�e;;rsen� ,�I��a�e�:.a:� BUJ.LOCH COUNTY, - , ' ' THEATRE N THE AMIJSIJ ewmgton WI. THE HEART OF GEORGIA, MI and MIs Chalile Cone mote: MUTtON PICTIJR£S STAT£SBlJRO, I "WHEIlE NATURE SMILES" cd to Augu'!!a Wednesday and were ��---------------------- Ml s De v G cover was a VIsitor In )'Lrs H ylarke accompanied home by their daugh- A 'BI'lJL1CAL 1YRANA Savannah Monday Pineora Sunday ter MISS Aldina Cone. wno IS study E L Smith was a business VIsitor MIss Nell Mat un IS \ isittng' rcla, mg at the Univeraity Hospital Miss t i es in Savannah Feb. -

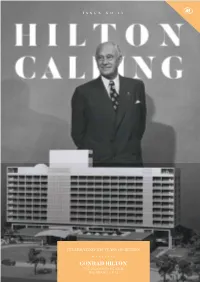

CONRAD HILTON the VISIONARY BEHIND the BRAND – P.12 Visit → Businessventures.Com.Mt

ISSUE NO.13 CELEBRATING 100 YEARS OF HILTON CONRAD HILTON THE VISIONARY BEHIND THE BRAND – P.12 Visit → businessventures.com.mt Surfacing the most beautiful spaces Marble | Quartz | Engineered Stone | Granite | Patterned Tiles | Quartzite | Ceramic | Engineered Wood Halmann Vella Ltd, The Factory, Mosta Road, Lija. LJA 9016. Malta T: (+356) 21 433 636 E: [email protected] www.halmannvella.com Surfacing the most beautiful spaces Marble | Quartz | Engineered Stone | Granite | Patterned Tiles | Quartzite | Ceramic | Engineered Wood Halmann Vella Ltd, The Factory, Mosta Road, Lija. LJA 9016. Malta T: (+356) 21 433 636 E: [email protected] www.halmannvella.com FOREWORD Hilton Calling Dear guests and friends of the Hilton Malta, Welcome to this very special edition of our magazine. The 31st of May 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of the opening of the first Hilton hotel in the world, in Cisco, Texas, in the United States of America. Since that milestone date in 1919, the brand has gone from strength to strength. Globally, there are currently just under 5700 hotels, in more than 100 countries, under a total of 17 brands, with new properties opening every day. Hilton has been EDITOR bringing memorable experiences to countless guests, clients and team members Diane Brincat for a century, returned value to the owners who supported it, and made a strongly positive impact on the various communities in which it operates. We at the Hilton MAGAZINE COORDINATOR Malta are proud to belong to this worldwide family, and to join in fulfilling its Rebecca Millo mission – in Conrad Hilton’s words, to ‘fill the world with the light and warmth of hospitality’ – for at least another 100 years. -

TDN AMERICA TODAY Through the Race Very Strongly and Had That Kick at the Finish Off BERNARDINI DEAD at 18 a Fast Pace

SATURDAY, JULY 31, 2021 BERNARDINI DEAD AT 18 NAVARRO TO CHANGE 'NOT GUILTY' PLEA IN INTERNATIONAL DOPING SCANDAL By T.D. Thornton Barred trainer Jorge Navarro, the most notorious and prominent defendant in the international racehorse doping scandal that rocked the racing industry when the feds arrested 28 alleged conspirators in March 2020, has just been granted an Aug. 11 change-of-plea hearing at which he is expected to alter his initial "not guilty" plea from last year. This bombshell change in the case could mean a new pleading of "guilty" is in the pipeline for Navarro, perhaps as part of a sentencing bargain that has played out behind the scenes between federal prosecutors and defense attorneys. Within the past week, two other alleged co-conspirators-a veterinarian and a drug distributor-have either already changed their pleas to guilty or are expected to do so at an upcoming Bernardini | Darley photo hearing. Cont. p11 Classic winner and leading sire Bernardini (A.P. Indy-Cara Rafaela, by Quiet American) was euthanized July 30 at Darley's IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Jonabell Farm in Central Kentucky due to complications from SUESA STORMS TO KING GEORGE GLORY laminitis. The 18-year-old stallion, a homebred for Sheikh Suesa (Ire) (Night of Thunder {Ire}) sprung a mild surprise Mohammed's operation, has stood at Jonabell since he was when saluting in the G2 King George Qatar S. during the Qatar retired for the 2007 breeding season. Goodwood Festival on Friday. Click or tap here to go straight ABernardini was one of a kind,@ said Michael Banahan, director to TDN Europe. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

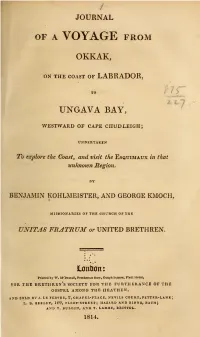

Journal of a Voyage from Okkak : on the Coast Of

/ JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE FROM OKKAK, ON THE COAST OF LABRADOR, TO UNGAVA BAY, WESTWARD OF CAPE CIIUDLEIGH; UNDERTAKEN To explore the Coast, and visit the Esquimaux in that unknown Region, BENJAMIN KOHLMEISTER, AND GEORGE KMOCH, MISSIONARIES OF THE CHURCH OF THE UNITAS FRATRUM or UNITED BRETHREN flxmtron: Printed by W. M'Dowall, Pemberton Row, Gough Square, Fleet Street, FOR THE BRETHREN'S SOCIETY FOR THE FURTHERANCE OF THE GOSPEL AMONG THE HEATHEN. FEBVRE, CHAPEL-PLACE, NEVILS COURT, FETTF.R-LA NE AND SOLD BY J. LE 2, J L. B. 8EELEY, 169, FLEET-STREET; HAZARD AND BINNS, BATH*, AND T. BULGIN, AND T. LAMBE, BRISTOL. 1814. io \S. JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE, INTRODUCTION. FOR these many years past, a considerable number of Esquimaux have been in the annual practice of visiting the three missionary establishments of the United Brethren on the coast of Labrador, Okkak, Nain, and Hopedale, chiefly with a view to barter, or to see those of their friends and ac- quaintance, who had become obedient to the gospel, and lived together in Christian fellowship, enjoying the instruction of the Missionaries. These people came mostly from the north, and some of them from a great distance. They reported, that the body of the Esquimaux nation lived near and beyond Cape Chud- leigh, which they call Killinek, and having conceived much friendship for the Missionaries, never failed to request, that some of them would come to their country, and even urged the formation of a new settlement, considerably to the north of Okkak. To these repeated and earnest applications the Mission- aries were the more disposed to listen, as it had been disco- vered, not many years after the establishment of the Mission in 177 lj, that that part of the coast on which, by the encou- ragement of the British government, the first settlement was made, was very thinly inhabited, and that the aim of the Mission, to convert the Esquimaux to Christianity, would be . -

The Culture of Wikipedia

Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia Good Faith Collaboration The Culture of Wikipedia Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. Foreword by Lawrence Lessig The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Web edition, Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. CC-NC-SA 3.0 Purchase at Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble | IndieBound | MIT Press Wikipedia's style of collaborative production has been lauded, lambasted, and satirized. Despite unease over its implications for the character (and quality) of knowledge, Wikipedia has brought us closer than ever to a realization of the centuries-old Author Bio & Research Blog pursuit of a universal encyclopedia. Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia is a rich ethnographic portrayal of Wikipedia's historical roots, collaborative culture, and much debated legacy. Foreword Preface to the Web Edition Praise for Good Faith Collaboration Preface Extended Table of Contents "Reagle offers a compelling case that Wikipedia's most fascinating and unprecedented aspect isn't the encyclopedia itself — rather, it's the collaborative culture that underpins it: brawling, self-reflexive, funny, serious, and full-tilt committed to the 1. Nazis and Norms project, even if it means setting aside personal differences. Reagle's position as a scholar and a member of the community 2. The Pursuit of the Universal makes him uniquely situated to describe this culture." —Cory Doctorow , Boing Boing Encyclopedia "Reagle provides ample data regarding the everyday practices and cultural norms of the community which collaborates to 3. Good Faith Collaboration produce Wikipedia. His rich research and nuanced appreciation of the complexities of cultural digital media research are 4. The Puzzle of Openness well presented. -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

The Hunt for Red October. Russia-Sweden Relations and a Missing Submarine

The Hunt for Red October. Russia-Sweden Relations and a Missing Submarine By Israel Shamir Region: Europe, Russia and FSU Global Research, August 01, 2015 Theme: History These days, Sweden is all agog. In the midst of the coldest summer in living history that deprived the Swedes of their normal sun-accumulating July routine, the country plunged into an exciting search for a Russian submarine in the Stockholm archipelago, and (as opposed to the previous rounds of this venerable Swedish maritime saga) this time they actually found the beast. Now we know for certain the Russians had intruded into Swedish waters! The Swedish admirals and the Guardian journalists probably feel themselves vindicated, as they always said so. Does it matter that the U-boat was sunk one hundred years ago, in 1916? Surely it does not, for the Russians are the same Russians and the sea is the same sea! I would continue in the same vein and have a lot of fun, but many innocent readers (especially on the internet) are not attuned for irony. If they read Swift’sModest Proposal, they’d call the police. For the benefit of the reader in whom is no guile (John 1:47), I’ll say it in plain words: the Swedish Navy and the great British newspaper Guardian made fools of themselves again, as they blamed the Russian president Putin for sending a submarine that turned out to be a one hundred year old war relic. | 1 The U-boat calledSom (Catfish) had been built in the US in 1901 for the Russian Navy, served in World War I and went down with all hands in 1916. -

Travis Sidak Thesis 2020. Making up a Drug Epidemic

MAKING UP A DRUG EPIDEMIC: CONSTRUCTING DRUG DISCOURSE DURING THE OPIOID EPIDEMIC IN ONTARIO By: Travis M. Sidak Bachelor of Art: Rhetoric and Writing, University of Winnipeg, 2017 A thesis presented to Ryerson University and York University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2020 © Travis M. Sidak, 2020 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. i i Making Up a Drug Epidemic: Constructing Drug Discourse During the Opioid Epidemic in Ontario Master of Arts 2020 Travis M. Sidak Communication and Culture Ryerson University & York University Abstract The current opioid epidemic has resulted in growing rates of overdose across the province with the introduction of fentanyl into illicit drug markets. What barriers are preventing policy makers from enacting emergency measures to save lives and how have those affected by the epidemic been categorically ignored? The following research critically analyzes drug discourse relating to the current opioid epidemic in Ontario and discusses why government responses to the epidemic have been delayed, and why they offer inferior measures to prevent growing mortality and morbidity. -

Cry of the Nameless

CRY 184 I am not a men - | am a free number! BULLETIN BOARD with real bullets ih Most Beautiful Event in the History of Mankind & ONE DAY ONLY—JULY 6TH, 1969 1’ I THE ONE MILLION DOLLAR GOLDEN ALTA A I OF THE UNIVERSAL WORLD CHURCH! I X WILL BE SEEN ONLY AT THE MIGHTY f TRANSUBSTANTIATiON COMM® ON f ffl JULY 6th—1969—10:00 A.M. B fhe 7th Wonder of the modern World! & fnothing like it on the fsce of the north! § I NEW ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND DOLLAR f; I THRONE OF GOD UPON THE GOLDEN AL TAR& Over mediocrity. Lb Attempted {Patterned J/lfter c77;e 777easure- Hello, INDESCRIBABLE! SPLENDIFEROUS! Hffl j RADIO KIEV Prisoner. X 8 AM SUNDAY The Universal World Church ij 87 ON DIAL 123 No. Lake St. Near Beverly end Alvarado SECTARIAN CHURCH Dn and Mrs. O. L. Jaggers Goodbye, Pray Nou\ Pay Sfay friends with your purest heart and motives. See Cavett. your focal Green Beret recruiter. (Free legal counsel taler Proposed for the first six applicants.) Dick For Churches HOUSTON, Tex. (AP) — It < may not be long before credit Only Teddy knows for sure. .. cards are used in churches to sweet replace the old collection plate. The National Association of Church Business Administra How to butter up an author; milk him forall he's worth. tors, which met in Houston this week, disclosed the possibilities of using credit cards for church Goodbye, In our next CRY issue: the life and loves of Wally W Weber, donations. ■ The association agreed that a daring expose. -

Noetics Lawrence Krader

Noetics Lawrence Krader ©2010 Cyril Levitt Editor’s Introduction Lawrence Krader passed away on November 15, 1998, after having produced what he considered to be the antepenultimate draft of his magnum opus on noetics. He planned to prepare the final draft for publication in the following year. In August 1998, during our last face- to-face meeting in Berlin, he reviewed the theory of noetics with me and felt confident that the manuscript he had completed to that point contained all the major ideas that he wished to present to the reading public. It was then a matter of fine-tuning. In preparing this manuscript for publication, I have exercised my editorial privilege and decided not to second guess the author in terms of clarifying ambiguities in the text, smoothing out cumbersome con- structions of language that would have surely been changed in the final draft, eliminate repetitive thoughts or passages, or adding and specifying further bibliographic detail that might be of help to the reader. I’ve performed some light editing, correcting spelling and grammar mistakes such as they were, and obvious errors, for example, where one thinker was identified in the text when it was clear that another was meant. I decided upon this strategy not only because I didn’t want to second-guess the intention of the author in matters of detail; in addition, I felt that the reader should wrestle with Krader’s words as he left them. The book will be a “rougher” and less elegant read, but the reader will hopefully benefit from this encounter with a manuscript in statu nascendi, a whole lacking the finishing touches and some elegant turns of phrase in a polished draft of which the author could say “this is my final product.” In a strange way, as the reader will discover, the lack of synthesis is a theme of noetics.