The Foreign-Policy Aspect of Mei Lanfang's Soviet Tour in 1935

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 04, 1949 Memorandum of Conversation Between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified February 04, 1949 Memorandum of Conversation between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong Citation: “Memorandum of Conversation between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong,” February 04, 1949, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, APRF: F. 39, Op. 1, D. 39, Ll. 54-62. Reprinted in Andrei Ledovskii, Raisa Mirovitskaia and Vladimir Miasnikov, Sovetsko-Kitaiskie Otnosheniia, Vol. 5, Book 2, 1946-February 1950 (Moscow: Pamiatniki Istoricheskoi Mysli, 2005), pp. 66-72. Translated by Sergey Radchenko. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113318 Summary: Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong discuss the independence of Mongolia, the independence movement in Xinjiang, the construction of a railroad in Xinjiang, CCP contacts with the VKP(b), the candidate for Chinese ambassador to the USSR, aid from the USSR to China, CCP negotiations with the Guomindang, the preparatory commisssion for convening the PCM, the character of future rule in China, Chinese treaties with foreign powers, and the Sino-Soviet treaty. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation On 4 February 1949 another meeting with Mao Zedong took place in the presence of CCP CC Politburo members Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, Ren Bishi, Zhu De and the interpreter Shi Zhe. From our side Kovalev I[van]. V. and Kovalev E.F. were present. THE NATIONAL QUESTION I conveyed to Mao Zedong that our CC does not advise the Chinese Com[munist] Party to go overboard in the national question by means of providing independence to national minorities and thereby reducing the territory of the Chinese state in connection with the communists' take-over of power. -

The Soul of Beijing Opera: Theatrical Creativity and Continuity in the Changing World, by Li Ruru

The Soul of Beijing Opera: Theatrical Creativity and Continuity in the Changing World, by Li Ruru Author Mackerras, Colin Published 2010 Version Version of Record (VoR) Copyright Statement © 2010 CHINOPERL. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/71170 Link to published version https://chinoperl.osu.edu/journal/back-volumes-2001-2010 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au CHINOPERL Papers No. 29 The Soul of Beijing Opera: Theatrical Creativity and Continuity in the Changing World. By Li Ruru, with a foreword by Eugenio Barba. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010, xvi + 335 pp. 22 illus. Paper $25.00; Cloth $50.00. Among the huge advances made in studies of Chinese theatre in European languages over recent decades, those on the genre now normally called jingju 京劇 in Chinese and referred to in English as Peking opera or Beijing opera occupy a significant place. Theatre is by its nature multidisciplinary in the sense that it covers history, politics, performance, literature, society and other fields. Among other book-length studies published in the last few years, this art has yielded those with a historical perspective such as Joshua Goldstein‘s Drama Kings: Players and Publics in the Re-creation of Peking Opera, 1870–1937 (University of California Press, 2007) and those focusing more on stage aesthetics such as Alexandra B. Bonds‘ Beijing Opera Costumes: The Visual Communication of Character and Culture (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2008). -

Also by Jung Chang

Also by Jung Chang Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China Mao: The Unknown Story (with Jon Halliday) Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF Copyright © 2019 by Globalflair Ltd. All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Vintage, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2019. www.aaknopf.com Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019943880 ISBN 9780451493507 (hardcover) ISBN 9780451493514 (ebook) ISBN 9780525657828 (open market) Ebook ISBN 9780451493514 Cover images: (The Soong sisters) Historic Collection / Alamy; (fabric) Chakkrit Wannapong / Alamy Cover design by Chip Kidd v5.4 a To my mother Contents Cover Also by Jung Chang Title Page Copyright Dedication List of Illustrations Map of China Introduction Part I: The Road to the Republic (1866–1911) 1 The Rise of the Father of China 2 Soong Charlie: A Methodist Preacher and a Secret Revolutionary Part II: The Sisters and Sun Yat-sen (1912–1925) 3 Ei-ling: A ‘Mighty Smart’ Young Lady 4 China Embarks on Democracy 5 The Marriages of Ei-ling and Ching-ling 6 To Become Mme Sun 7 ‘I wish to follow the example of my friend Lenin’ Part III: The Sisters and Chiang Kai-shek (1926–1936) 8 Shanghai Ladies 9 May-ling Meets the Generalissimo 10 Married to a Beleaguered -

Conspiracies Behind Xi'an Coup

Conspiracies Behind Xi'an Coup by Ah Xiang [Excerpts from “Red Terror & White Terror” ] Secret KMT-CCP Direct Contacts In Multiple Channels Throughout 1935-1936, emissaries for peace or ceasefire talks shuttled between KMT and CCP in secrecy. Chiang Kai-shek's KMT was also in talks with USSR. In early 1935, Chiang Kai-shek dispatched "Yan Huiqing cultural delegation" to USSR, and later, Chiang Kai-shek dispatched Deng Wenyi as military attache to Moscow. In autumn of 1935, Deng Wenyi returned to China and briefed Chiang on Stalin's support in the fight against Japan. In the winter of 1935, Deng Wenyi, after return to Moscow, was authorized to contact CCP's Comintern rep Wang Ming in Moscow. After several talks between Deng Wenyi and Wang Ming, CCP Comintern delegation sent Pan Hannian back to China for working on bilateral party talks. Before departing Moscow, Pan Hannian met with Deng Wenyi. Pan Hannian and Hu Yuzhi returned to HK in early May 1936. Pan wrote to KMT's Chen Guofu for liaison in HK, while Hu Yuzhi went to Shanghai the next month for seeking a passage to CCP enclave in northern Shenxi. In Shanghai, Hu Yuzhi contacted leftist writer Mao Dun and learnt that CCP Shenxi had sent messenger Feng Xuefeng to Shanghai. Hu Yuzhi and Feng Xuefeng immediately went to HK for seeing Pan Hannian. Feng Xuefeng disclosed to Pan Hannian that CCP Shanghai possessed secret telegraph set (possibly the set inside of Louise Alley's residence?). At this time, Chen Guofu dispatched chief of staff Zhang Chong of KMT Central Organization Investigation Section to HK, with an invitation for Pan Hannian to visit KMT headquarter in Nanking. -

From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-Graphical Dictionary of Republican China Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot

From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-graphical Dictionary of Republican China Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot To cite this version: Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot. From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-graphical Dictionary of Republican China. Journal of Historical Network Research, In press. halshs-03213995 HAL Id: halshs-03213995 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03213995 Submitted on 8 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ARMAND, CÉCILE HENRIOT, CHRISTIAN From Textual to Historical Net- works: Social Relations in the Bio- graphical Dictionary of Republi- can China Journal of Historical Network Research x (202x) xx-xx Keywords Biography, China, Cooccurrence; elites, NLP From Textual to Historical Networks 2 Abstract In this paper, we combine natural language processing (NLP) techniques and network analysis to do a systematic mapping of the individuals mentioned in the Biographical Dictionary of Republican China, in order to make its underlying structure explicit. We depart from previous studies in the distinction we make between the subject of a biography (bionode) and the individuals mentioned in a biography (object-node). We examine whether the bionodes form sociocentric networks based on shared attributes (provincial origin, education, etc.). -

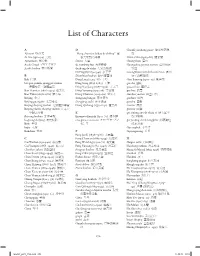

List of Characters

List of Characters A D Guanli yaoshang guize 䭉䎮喍⓮夷 Ajinomi 味の美 “Dang chuntian laidao de shihou” 䔞 ⇯ Ai Xia (1912–34) 刦曆 㗍⣑Ἦ⇘䘬㗪῁ Guan Zilan (1903–86) 斄䳓嗕 Ajinomoto 味の素 Daxue ⣏⬠ Guangzhou ⺋ⶆ Asahi Graph アサヒグラフ da yundong hui ⣏忳≽㚫 Guangzhou guomin xinwen ⺋ⶆ⚳㮹 Asahi shinbun 朝日新聞 dazhong de yishu ⣏䛦䘬喅埻 㕘倆 Di Pingzi (1879–1941) 䉬⸛⫸ Guangzhou nuzi shifan xuexiao ⺋ⶆ B Dianshizai huabao 溆䞛滳䔓⟙ ⤛⫸ⷓ䭬⬠㟉 Bali 湶 Ding Ling (1904–86) ᶩ䍚 Guo Jianying (1907–79) 悕⺢劙 baoguo yumin, qiangguo fumin Ding Song (1891-1969) ᶩあ guochi ⚳」 ᾅ⚳做㮹炻⻟⚳㮹 Ding Wenjiang (1887–1936) ᶩ㔯㰇 guocui hua ⚳䱡䔓 Bao Tianxiao (1876–1973) ⊭⣑䪹 Ding Yanyong (1902-78) ᶩ埵 guohua ⚳䔓 Bao Yahui (1898-1982) 欹Ṇ㘱 Dong Chuncai (1905–90) 吋䲼ㇵ Guohua yuekan ⚳䔓㚰↲ Beijing ⊿Ṕ dongfang bingfu 㜙㕡䕭⣓ guohuo ⚳屐 Beijing guangshe ⊿Ṕ䣦 Dongfang zazhi 㜙㕡暄娴 guoshu ⚳埻 Beijing sheying xuehui ⊿Ṕ㓅⼙⬠㚫 Dong Qichang (1555–1636) 吋℞㖴 Guotai ⚳㲘 Beiping daxue sheying xuehui ⊿⸛⣏ guoxue ⚳⬠ ⬠㓅⼙⬠㚫 E gei xinling zuo de shafa yi 䴎⽫曰⛸ Beiyang huabao ⊿㲳䔓⟙ Enomoto Kenichi (1904-70) 榎本健一 䘬㱁䘤㢭 boguang shuying 㲊㧡⼙ ero, guro, nansensu エロ・グロ・ナン gei yanjing chi de bingqilin 䴎䛤䜃⎫ Buin ิၨ センス 䘬⅘㵯㵳 bujie ᶵ㻼 Gyeongbok ઠฟ Bukchon ีᆀ F Gyeongseong ઠໜ Fang Junbi (1898–1986) 㕡⏃䑏 C Feng Chaoran (1882–1954) 楖崭䃞 H Cai Weilian (1904-40) 哉⦩ Feng Wenfeng (1900-71) 楖㔯沛 Haiguo tuzhi 㴟⚳⚾⽿ Cai Yuanpei (1868–1940) 哉⃫➡ Feng Yuxiang (1882–1948) 楖䌱䤍 Haishang fanhua 㴟ᶲ䷩厗 Chenbao fukan 㘐⟙∗↲ Fengyue huabao 桐㚰䔓⟙ Hamada Masuji (1892-1938) 浜田増治 Chen Baoyi (1893–1945) 昛㉙ᶨ Feng Zikai (1898–1975) 寸⫸ミ Hanbok ዽฟ Chen Duxiu (1879–1942) 昛䌐䥨 Fudan daxue ⽑㖎⣏⬠ Hankou 㻊⎋ -

The Politics of Celebrity in Madame Chiang Kai-Shek's

China’s Prima Donna: The Politics of Celebrity in Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s 1943 U.S. Tour By Dana Ter Columbia University |London School of Economics International and World History |Dual Master’s Dissertation May 1, 2013 | 14,999 words 1 Top: Madame Chiang speaking at a New Life Movement rally, taken by the author at Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, Taipei, Taiwan, June 2012. Front cover: Left: Allene Talmey, “People and Ideas: May Ling Soong Chiang,” Vogue 101(8), (April 15, 1943), 34. Right: front page of the Kansas City Star, February 23, 1943, Stanford University Hoover Institution (SUHI), Henry S. Evans papers (HSE), scrapbook. 2 Introduction: It is the last day of March 1943 and the sun is beaming into the window of your humble apartment on Macy Street in Los Angeles’ “Old Chinatown”.1 The day had arrived, Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s debut in Southern California. You hurry outside and push your way through a sea of black haired-people, finding an opening just in time to catch a glimpse of China’s First Lady. There she was! In a sleek black cheongsam, with her hair pulled back in a bun, she smiled graciously as her limousine slid through the adoring crowd, en route to City Hall. The split second in which you saw her was enough because for the first time in your life you were proud to be Chinese in America.2 As the wife of the Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, from February-April 1943, Madame Chiang, also known by her maiden name, Soong Mayling, embarked on a carefully- crafted and well-publicized tour to rally American material and moral support for China’s war effort against the Japanese. -

Please Click Here to Download

No.1 October 2019 EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Tobias BIANCONE, GONG Baorong EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS (in alphabetical order by Pinyin of last name) Tobias BIANCONE, Georges BANU, Christian BIET, Marvin CARLSON, CHEN Jun, CHEN Shixiong, DING Luonan, Erika FISCHER-LICHTE, FU Qiumin, GONG Baorong, HE Chengzhou, HUANG Changyong, Hans-Georg KNOPP, HU Zhiyi, LI Ruru, LI Wei, LIU Qing, LIU Siyuan, Patrice PAVIS, Richard SCHECHNER, SHEN Lin, Kalina STEFANOVA, SUN Huizhu, WANG Yun, XIE Wei, YANG Yang, YE Changhai, YU Jianchun. EDITORS WU Aili, CHEN Zhongwen, CHEN Ying, CAI Yan CHINESE TO ENGLISH TRANSLATORS HE Xuehan, LAN Xiaolan, TANG Jia, TANG Yuanmei, YAN Puxi ENGLISH CORRECTORS LIANG Chaoqun, HUANG Guoqi, TONG Rongtian, XIONG Lingling,LIAN Youping PROOFREADERS ZHANG Qing, GUI Han DESIGNER SHAO Min CONTACT TA The Center Of International Theater Studies-S CAI Yan: [email protected] CHEN Ying: [email protected] CONTENTS I 1 No.1 CONTENTS October 2019 PREFACE 2 Empowering and Promoting Chinese Performing Arts Culture / TOBIAS BIANCONE 4 Let’s Bridge the Culture Divide with Theatre / GONG BAORONG STUDIES ON MEI LANFANG 8 On the Subjectivity of Theoretical Construction of Xiqu— Starting from Doubt on “Mei Lanfang’s Performing System” / CHEN SHIXIONG 18 The Worldwide Significance of Mei Lanfang’s Performing Art / ZOU YUANJIANG 31 Mei Lanfang, Cheng Yanqiu, Qi Rushan and Early Xiqu Directors / FU QIUMIN 46 Return to Silence at the Golden Age—Discussion on the Gains and Losses of Mei Lanfang’s Red Chamber / WANG YONGEN HISTORY AND ARTISTS OF XIQU 61 The Formation -

New Actresses and Urban Publics in Early Republican Beijing Title

Carnegie Mellon University MARIANNA BROWN DIETRICH COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements Doctor of Philosophy For the Degree of New Actresses and Urban Publics in Early Republican Beijing Title Jiacheng Liu Presented by History Accepted by the Department of Donald S. Sutton August 1, 2015 Readers (Director of Dissertation) Date Andrea Goldman August 1, 2015 Date Paul Eiss August 1, 2015 Date Approved by the Committee on Graduate Degrees Richard Scheines August 1, 2015 Dean Date NEW ACTRESSES AND URBAN PUBLICS OF EARLY REPUBLICAN BEIJING by JIACHENG LIU, B.A., M. A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the College of the Marianna Brown Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Carnegie Mellon University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY August 1, 2015 Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the help from many teachers, colleages and friends. First of all, I am immensely grateful to my doctoral advisor, Prof. Donald S. Sutton, for his patience, understanding, and encouragement. Over the six years, the numerous conversations with Prof. Sutton have been an unfailing source of inspiration. His broad vision across disciplines, exacting scholarship, and attention to details has shaped this study and the way I think about history. Despite obstacle of time and space, Prof. Andrea S. Goldman at UCLA has generously offered advice and encouragement, and helped to hone my arguments and clarify my assumptions. During my six-month visit at UCLA, I was deeply affected by her passion for scholarship and devotion to students, which I aspire to emulate in my future career. -

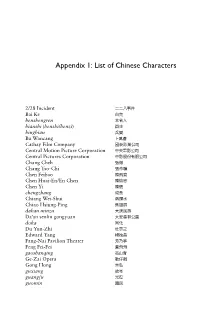

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters 2/28 Incident 二二八事件 Bai Ke 白克 benshengren 本省人 bianshi (benshi/benzi) 辯士 bingbian 兵變 Bu Wancang 卜萬蒼 Cathay Film Company 國泰影業公司 Central Motion Picture Corporation 中央電影公司 Central Pictures Corporation 中影股份有限公司 Chang Cheh 張徹 Chang Tso-Chi 張作驥 Chen Feibao 陳飛寶 Chen Huai-En/En Chen 陳懷恩 Chen Yi 陳儀 chengzhang 成長 Chiang Wei- Shui 蔣謂水 Chiao Hsiung- Ping 焦雄屏 dahan minzu 大漢民族 Da’an senlin gongyuan 大安森林公園 doka 同化 Du Yun- Zhi 杜雲之 Edward Yang 楊德昌 Fang- Nai Pavilion Theater 芳乃亭 Feng Fei- Fei 鳳飛飛 gaoshanqing 高山青 Ge- Zai Opera 歌仔戲 Gong Hong 龔弘 guxiang 故鄉 guangfu 光復 guomin 國民 188 Appendix 1 guopian 國片 He Fei- Guang 何非光 Hou Hsiao- Hsien 侯孝賢 Hu Die 胡蝶 Huang Shi- De 黃時得 Ichikawa Sai 市川彩 jiankang xieshi zhuyi 健康寫實主義 Jinmen 金門 jinru shandi qingyong guoyu 進入山地請用國語 juancun 眷村 keban yingxiang 刻板印象 Kenny Bee 鍾鎮濤 Ke Yi-Zheng 柯一正 kominka 皇民化 Koxinga 國姓爺 Lee Chia 李嘉 Lee Daw- Ming 李道明 Lee Hsing 李行 Li You-Xin 李幼新 Li Xianlan 李香蘭 Liang Zhe- Fu 梁哲夫 Liao Huang 廖煌 Lin Hsien- Tang 林獻堂 Liu Ming- Chuan 劉銘傳 Liu Na’ou 劉吶鷗 Liu Sen- Yao 劉森堯 Liu Xi- Yang 劉喜陽 Lu Su- Shang 呂訴上 Ma- zu 馬祖 Mao Xin- Shao/Mao Wang- Ye 毛信孝/毛王爺 Matuura Shozo 松浦章三 Mei- Tai Troupe 美臺團 Misawa Mamie 三澤真美惠 Niu Chen- Ze 鈕承澤 nuhua 奴化 nuli 奴隸 Oshima Inoshi 大島豬市 piaoyou qunzu 漂游族群 Qiong Yao 瓊瑤 qiuzhi yu 求知慾 quanguo gejie 全國各界 Appendix 1 189 renmin jiyi 人民記憶 Ruan Lingyu 阮玲玉 sanhai 三害 shandi 山地 Shao 邵族 Shigehiko Hasumi 蓮實重彦 Shihmen Reservoir 石門水庫 shumin 庶民 Sino- Japanese Amity 日華親善 Society for Chinese Cinema Studies 中國電影史料研究會 Sun Moon Lake 日月潭 Taiwan Agricultural Education Studios -

Remaking Chinese Cinema: Through the Prism of Shanghai, Hong Kong

Remaking Chinese Cinema Through the Prism of Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Hollywood Yiman Wang © 2013 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved First published in the United States of America by University of Hawai‘i Press Published for distribution in Australia, Southeast and East Asia by: Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org ISBN 978-988-8139-16-3 (Paperback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed by University of Hawai‘i Production Department Printed and bound by Kings Time Printing Press Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments | xi Introduction | 1 1. The Goddess: Tracking the “Unknown Woman” from Hollywood through Shanghai to Hong Kong | 18 2. Family Resemblance, Class Conflicts: Re-version of the Sisterhood Singsong Drama | 48 3. The Love Parade Goes On: “Western-Costume Cantonese Opera Film” and the Foreignizing Remake | 82 4. Mr. Phantom Goes to the East: History and Its Afterlife from Hollywood to Shanghai and Hong Kong | 113 Conclusion: Mr. Undercover Goes Global | 143 Notes | 165 Bibliography | 191 Filmography | 207 Index | 211 ix CHAPTER 1 The Goddess Tracking the “Unknown Woman” from Hollywood through Shanghai to Hong Kong Maternal melodramas featuring self-sacrificial mothers abound in the history of world cinema. From classic Hollywood women’s films to Lars von Trier’s new-millennium musical drama Dancer in the Dark (2000), the mother figure works tirelessly for her child only to eventually withdraw herself from the child’s life in order to secure a prosperous future for him or her.1 In this chap- ter, I trace the Shanghai and Hong Kong remaking of an exemplary Hollywood maternal melodrama, Stella Dallas, in the 1930s. -

HU Die Hú Dié 胡 蝶 1907–1989 Film Actress

◀ Household Responsibility System Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. HU Die Hú Dié 胡 蝶 1907–1989 Film actress “Butterfly” Hu was the most famous Chinese (Meng Jiangnü, Madame White Snake, Zhu Yingtai, all actress of the silent and early sound era. Like of which are exemplary though “doomed” lovers in clas- many contemporaries, she performed under a sical Chinese oral tradition and fiction). In 1928 she par- stage name, which followed her throughout a layed this success into a high-paying contract with the career that spanned four decades. Once an offi- cial representative of China’s film industry un- Hu Die (1907– 1989). “Butterfly,” as she was known der the Nationalist Party, she founded her own to her adoring fans, reached won great acclaim for production company before retiring in 1967. playing a pair of estranged twins.. nown during the 1930s as China’s “Film Queen,” “Butterfly” Hu’s personal name was Ruihua and her father a high-ranking customs inspector for the Beijing-Fengtian Railway. Moving with her family from Shanghai to numerous cities in northern China al- lowed Hu to acquire fluency in several Chinese dialects. Although a film actress from 1925 onward, these linguistic abilities proved extremely valuable in aiding Hu to suc- cessfully make the transition from silent films to “talkies.” She starred in the Shanghai film industry’s first partial- sound production (the film was recorded with a complete soundtrack, but this was played back on a separate disk which accompanied the feature), The Singing Girl Red Pe- ony (1931), which also made her a figure in the burgeoning world of mass-produced popular music.