Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Egypt Under the Ptolemies

UC-NRLF $C lb EbE THE HISTORY OF EGYPT THE PTOLEMIES. BY SAMUEL SHARPE. LONDON: EDWARD MOXON, DOVER STREET. 1838. 65 Printed by Arthur Taylor, Coleman Street. TO THE READER. The Author has given neither the arguments nor the whole of the authorities on which the sketch of the earlier history in the Introduction rests, as it would have had too much of the dryness of an antiquarian enquiry, and as he has already published them in his Early History of Egypt. In the rest of the book he has in every case pointed out in the margin the sources from which he has drawn his information. » Canonbury, 12th November, 1838. Works published by the same Author. The EARLY HISTORY of EGYPT, from the Old Testament, Herodotus, Manetho, and the Hieroglyphieal Inscriptions. EGYPTIAN INSCRIPTIONS, from the British Museum and other sources. Sixty Plates in folio. Rudiments of a VOCABULARY of EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPHICS. M451 42 ERRATA. Page 103, line 23, for Syria read Macedonia. Page 104, line 4, for Syrians read Macedonians. CONTENTS. Introduction. Abraham : shepherd kings : Joseph : kings of Thebes : era ofMenophres, exodus of the Jews, Rameses the Great, buildings, conquests, popu- lation, mines: Shishank, B.C. 970: Solomon: kings of Tanis : Bocchoris of Sais : kings of Ethiopia, B. c. 730 .- kings ofSais : Africa is sailed round, Greek mercenaries and settlers, Solon and Pythagoras : Persian conquest, B.C. 525 .- Inarus rebels : Herodotus and Hellanicus : Amyrtaus, Nectanebo : Eudoxus, Chrysippus, and Plato : Alexander the Great : oasis of Ammon, native judges, -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01205-9 — Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World Nathanael J

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01205-9 — Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World Nathanael J. Andrade Index More Information Index Maccabees, , , , Armenian tiara and Persian dress, Maccabees, , , , , as Roman citizen, Commagene as hearth, Abgar X (c. –), , , compared with Herod I, Abgarid dynasty of Edessa, culture and cult sustained by gods, Abidsautas, Aurelios (Beth Phouraia), , dexiosis, , , Galatians, , Achaemenid Persians, , , , , , , , Greek and Persian divinities, , , , , Greek, Persian, and Armenian ancestry, , Acts of the Apostles, Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem), , , hierothesion at Nemrud Dag,˘ , , Agrippa, Marcus Vipsanius, , hybridity, , , Akkadian cuneiform, , , , , , , Nemrud DagasDelphi,˘ Alexander III of Macedon (the Great) (– organizes regional community, , , bce), , , , , , , , , , priests in Persian clothing, , , , , , , sacred writing of, Alexander of Aboniteichos (false prophet), , statues of himself, ancesters, and gods, successors patronize poleis, Alexander, Markos Aurelios of Markopolis, trends of his reign, , Anath/Anathenes, , , , , , , Tych¯e, , Antiochus I, Seleucid (– bce), , , Antioch among the Jerusalemites (Jerusalem), Antiochus II, Seleucid (– bce), , , , , , , , , , Antiochus III, Seleucid (– bce), , , Antioch at Daphne, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , Antiochus IV of Commagene (– ce), , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , Antiochus IV, Seleucid (– bce), , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , bilingual/multilingual Alexander, , , , , , , , , -

View / Download 2.4 Mb

Lucian and the Atticists: A Barbarian at the Gates by David William Frierson Stifler Department of Classical Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ William A. Johnson, Supervisor ___________________________ Janet Downie ___________________________ Joshua D. Sosin ___________________________ Jed W. Atkins Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classical Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Lucian and the Atticists: A Barbarian at the Gates by David William Frierson Stifler Department of Classical Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ William A. Johnson, Supervisor ___________________________ Janet Downie ___________________________ Joshua D. Sosin ___________________________ Jed W. Atkins An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classical Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by David William Frierson Stifler 2019 Abstract This dissertation investigates ancient language ideologies constructed by Greek and Latin writers of the second and third centuries CE, a loosely-connected movement now generally referred to the Second Sophistic. It focuses on Lucian of Samosata, a Syrian “barbarian” writer of satire and parody in Greek, and especially on his works that engage with language-oriented topics of contemporary relevance to his era. The term “language ideologies”, as it is used in studies of sociolinguistics, refers to beliefs and practices about language as they function within the social context of a particular culture or set of cultures; prescriptive grammar, for example, is a broad and rather common example. The surge in Greek (and some Latin) literary output in the Second Sophistic led many writers, with Lucian an especially noteworthy example, to express a variety of ideologies regarding the form and use of language. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship. WILLIAMS-REED, ERIS,KATHLYN,LAURA How to cite: WILLIAMS-REED, ERIS,KATHLYN,LAURA (2018) Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13052/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship Eris Kathlyn Laura Williams-Reed A thesis submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics and Ancient History Durham University 2018 Acknowledgments It is a joy to recall the many people who, each in their own way, made this thesis possible. Firstly, I owe a great deal of thanks to my supervisor, Ted Kaizer, for his support and encouragement throughout my doctorate, as well as my undergraduate and postgraduate studies. -

Popular Cult – North Syria

CHAPTER 4 POPULAR CULT – NORTH SYRIA In this chapter the emphasis moves away from the state-controlled production of official images – so important to the understanding of the ideology of the court – and into a world of regional polities. While the coin evidence may show the religious penchant of a ruler, the everyday beliefs of the population are better expressed through the building of temples and shrines, whether they be erected through public or private expense. The terminology used in the title of the chapter, „popular cult‟, is intended to take in all manner of religious activity for which we have evidence, where the activity lay more with the population at large than simply the whim of the king. The nature of archaeological survival has necessitated that this chapter be dominated by sanctuaries and temples, although there are exceptions. Excavations at the great metropolis of Antioch for example have not revealed the remains of any Seleukid period temples but Antioch may still prove informative. Whilst some, or perhaps all, of the Hellenistic temple constructions discussed below may have been initiated by the king and his council, the historic and epigraphic record is unfortunately too sporadic to say for certain. While the evidence discussed in Chapter 2.3 above suggests that all must have been ratified by the satrapal high-priest, the onus of worship appears to have been locally driven. The geographic division „north Syria‟ is used here to encompass the Levantine territory which was occupied by Seleukos I Nikator following the victory at Ipsos in 301 BC, that is to say, the part of Syria which came first under the control of the Seleukids. -

Christ-Bearers and Fellow- Initiates: Local Cultural Life and Christian Identity in Ignatius’ Letters1

HARLAND/CHRIST-BEARERS 481 Christ-Bearers and Fellow- Initiates: Local Cultural Life and Christian Identity in Ignatius’ Letters1 PHILIP A. HARLAND In writing to Christian congregations in the cities of Roman Asia, Ignatius draws on imagery from Greco-Roman cultural life to speak about the identity of the Christians. Scholars have given some attention to the cultural images which Ignatius evokes, but often in a cursory way and rarely, if ever, with reference to local religious life. Concentrating on Ignatius’ characterization of Christian groups as “Christ-bearers” and “fellow-initiates” (Eph. 9.2; 12.2), the paper explores neglected archeological and epigraphical evidence from Asia Minor (and Syria) regarding processions, mysteries, and associations. This sheds important light on what Ignatius may have had in mind and, perhaps more importantly, what the listeners or readers of Ignatius’ letters in these cities would think of when he spoke of their identity in this way. 1. INTRODUCTION Ignatius of Antioch uses several analogies and metaphors in his letters to speak about the identity of Christian assemblies in Roman Asia. The Christians at Ephesos, for instance, are likened to a choral group in a temple, “attuned to the bishop as strings to a lyre” (Eph. 4; cf. Phld. 1.2). They are “fellow-initiates” (symmystai) of Paul that share in the “myster- ies” (Eph. 12.2; 19.1; cf. Magn. 9.1; Trall. 2.3). Together they take part in 1. An earlier version of this paper was read at the Canadian Society of Biblical Studies in Toronto, May 2002. I am grateful to the participants for their feedback. -

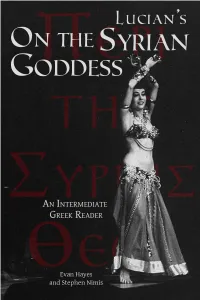

On the Syrian Goddess

Lucian’s On the Syrian Goddess An Intermediate Greek Reader Greek text with running vocabulary and commentary Evan Hayes and Stephen Nimis Lucian’s On the Syrian Goddess: An Intermediate Greek Reader Greek text with Running Vocabulary and Commentary First Edition (Revised Dec. 2012) © 2012 by Evan Hayes and Stephen Nimis All rights reserved. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. The authors have made a version of this work available (via email) under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. The terms of the license can be accessed at creativecommons.org. Accordingly, you are free to copy, alter and distribute this work under the following conditions: 1. You must attribute the work to the author (but not in a way that suggests that the author endorses your alterations to the work). 2. You may not use this work for commercial purposes. 3. If you alter, transform or build up this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license as this one. The Greek text is based on the Loeb edition of Lucian, first published in 1921. Unless otherwise noted, all images appearing in this edition are in the public domain. Those images under copyright may not be reproduced without permission from the artist. ISBN: 978-0-9832228-8-0 Published by Faenum Publishing, Ltd. -

Mic 60-4116 MORIN, Paul John. the CULT of DEA SYRIA in THE

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received Mic 60-4116 MORIN, Paul John. THE CULT OF DEA SYRIA IN THE GREEK WORLD. The Ohio State University, Ph.D ., 1960 Language and Literature, classical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE CULT OF DEA SYRIA IN THE GREEK WORLD DISSERTATION Presented In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Paul John Morin, A.B. The Ohio State University 1960 Approved by AdvYser Department of Classical Languages Quanti sunt qul norint visu vel auditu A targatin Syrorum? (Tert. Ad Nationes, II, 8) ii PREFACE Our only extensive literary source for the cult of Dea Syria, pertaining either to Syria or to the Greek world, is Lucian's treatise. Ilept Tfjs ZupCr]s Geou .1 This is a precious document, not only because it is the only work devoted entirely to the Syrian Goddess, but also be cause when it can be tested by archaeology and philology it is found to be a reliable eyewitness account of the re ligion of Hierapolis in the second century of our era. Lucian's authorship of this work has been seriously doubted and because of its peculiarities (to mention only the I- onic dialect) the question is not likely to be settled. Perhaps in their eagerness to have a source of unassailable quality, religionists tend to support Lucian's authorship; students of Lucian, on the other hand, are divided. The Question, however, has never been investigated satisfacto rily, so that further pronouncements at this point would be of little permanent value. -

On Greek Ethnography of the Near East the Case of Lucian's De Dea Syria

ON GREEK ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE NEAR EAST THE CASE OF LUCIAN'S DE DEA SYRIA Jane L. Lightfoot Near the river Euphrates in northern Syria, about twenty miles from the present border, is the modern town Membij, the ancient Hierapolis. The modern town gives barely a hint of its former greatness, but as its ancient name, the Holy City, indicates, it was the centre of a prestigious and arguably very ancient cult - that of Atargatis, the Syrian Goddess1. Partnered by the old Aramaic storm god, Hadad, Atargatis was an all- powerful benefactress, patroness of human life and promoter of fertility, queenly and merciful, and especially associated with life-giving water whose visible symbol were her sacred fish2. The cult had other distinctive features. It had priests who wore white, conical head-gear which bears an interesting resemblance to divine headgear on Hittite rock-carvings and suggests that the cult had preserved at least some very archaic features3. And somewhere on the fringes, the goddess had a retinue of noisy, self- castrating eunuch devotees, reminiscent of those of the goddess Cybele4. In (probably) the second century AD, this cult attracted the attention of a writer who was, I believe, Lucian of Samosata. He treated it to a minute and circumstantial eye witness account written in imitation of the ethnographical style of the classical Greek historian Herodotus, purporting to give its myths, cultic aetiologies, a physical description of the temple, the highlights of its sacred calendar and some of its more picturesque rituals and cultic personnel. The result, the De Dea Syria (henceforth DDS) is an important, celebrated, and highly controversial text, disputed at almost every level, but also much-cited as a uniquely rich description of a native religious centre functioning under Roman rule. -

The Stromata, Or Miscellanies Book 1

584 THE STROMATA, OR MISCELLANIES BOOK 1 CHAPTER 1 PREFACE THE AUTHOR’S OBJECT THE UTILITY OF WRITTEN COMPOSITIONS [Wants the beginning ]..........that you may read them under your hand, and may be able to preserve them. Whether written compositions are not to be left behind at all; or if they are, by whom? And if the former, what need there is for written compositions? and if the latter, is the composition of them to be assigned to earnest men, or the opposite? It were certainly ridiculous for one to disapprove of the writing of earnest men, and approve of those, who are not such, engaging in the work of composition. Theopompus and Timaeus, who composed fables and slanders, and Epicurus the leader of atheism, and Hipponax and Archilochus, are to be allowed to write in their own shameful manner. But he who proclaims the truth is to be prevented from leaving behind him what is to benefit posterity. It is a good thing, I reckon, to leave to posterity good children. This is the case with children of our bodies. But words are the progeny of the soul. Hence we call those who have instructed us, fathers. Wisdom is a communicative and philanthropic thing. Accordingly, Solomon says, “My son, if thou receive the saying of my commandment, and hide it with thee, thine ear shall hear wisdom.” He points out that the word that is sown is hidden in the soul of the learner, as in the earth, and this is spiritual planting. Wherefore also he adds, “And thou shalt apply thine heart to understanding, and apply it for the admonition of thy son.” For soul, me thinks, joined with soul, and spirit with spirit, in the sowing of the word, will make that which is sown grow and germinate. -

Dictionnaire Philosophes Antiques

DICTIONNAIRE DES PHILOSOPHES ANTIQUES CENTRE NATIONAL DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE DICTIONNAIRE DES PHILOSOPHES ANTIQUES publié sous la direction de RICHARD GOULET Chercheur au C. N. R. S. IV de Labeo à Ovidius C. N. R. S. ÉDITIONS 15, rue Malebranche, 75005 PARIS 2005 © CNRS Éditions, Paris, 2005 ISBN 2-271-06386-8 L 66 LUCIEN DE SAMOSATE 131 Social Context : ualde bella ? », CPh 93, 1998, p. 308-321). Mais sans succès, apparemment. Lucceius a parfois été vu comme un épicurien (12 C. Castner, Prosopography, p. 86-87), à cause de sa lettre de consolation à Cicéron après la mort de Tullia (13 N. DeWitt, « Epicurean Contubernium », TAPhA 67, 1936, p. 55-63, p. 60 surtout) et d’autre part pour sa manière d’écrire l’histoire, sans montrer de partialité et en usant de franchise (Fam. V 12, 4 : si liberius, ut consuesti). De même, son caractère imperturbable n’est pas sans faire penser à l’ataraxia chère aux épicuriens (Cicéron, Fam. V 13). Malheureusement, quand bien même il serait très intéressant de mettre en lumière une manière épicu- rienne d’écrire l’histoire ou, si l’on préfère, une influence de la philosophie épicurienne sur la rédaction de l’histoire à Rome, la prudence invite à conclure à l’absence de toute preuve décisive de l’épicurisme de Lucceius. YASMINA BENFERHAT. 66 LUCIEN DE SAMOSATE RE PIR2 L 370 115/125 – 180/190 Littérateur et penseur grec du IIe siècle ap. J.-C., dont on a conservé un grand nombre d’écrits satiriques qui souvent prennent en compte les idées et les représentants des écoles philosophiques mystiques et dogmatiques (pythago- risme, platonisme, aristotélisme et notamment stoïcisme), ainsi que, de façon générale, la figure des faux philosophes. -

Roads Not Taken: Untold Stories in Ovid's Metamorphoses

Accademia Editorale Roads Not Taken: Untold Stories in Ovid's Metamorphoses Author(s): Richard Tarrant Reviewed work(s): Source: Materiali e discussioni per l'analisi dei testi classici, No. 54 (2005), pp. 65-89 Published by: Fabrizio Serra editore Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40236260 . Accessed: 25/07/2012 10:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Fabrizio Serra editore and Accademia Editorale are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Materiali e discussioni per l'analisi dei testi classici. http://www.jstor.org RichardTarrant RoadsNotTaken: UntolaStones in Ovid'sMétamorphoses* 1 he title of this paper calls for an explanation,if not an apology. The reactions it provokes are, I suspect, not unlike those gener- ateciby the title of Henry Bardon'sfamous work La littératurefa- tine inconnue;discussing untold stories would appear to be as paradoxical,or even absurd, as writing about unknown texts. In fact the comparisonto Bardonis an apt one, in that each of our ti- tles is somewhat more dramatic-soundingthan our actual sub- ject: just as his