The Eye of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treating Two 18Th Century Maps of the Danube in Association with Google-Provided Imagery

ON THE DIGITAL REVIVAL OF HISTORIC CARTOGRAPHY: TREATING TWO 18TH CENTURY MAPS OF THE DANUBE IN ASSOCIATION WITH GOOGLE-PROVIDED IMAGERY Evangelos Livieratos Angeliki Tsorlini Maria Pazarli [email protected] Chrysoula Boutoura Myron Myridis Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Faculty of Surveying Engineering University Campus, Box 497 GRE - 541 24 Thessaloniki, Greece Abstract The great navigable Danube River (known as the Istros River to the Ancient Greeks and as one of the crucial ends of the Roman Empire northern territories) is an emblematic fluvial feature of the overall European historic and cultural heritage in the large. Originating in the German Black Forest as two small rivers (Brigach and Breg) converging at the town of Donaueschingen, Danube is flowing for almost 2850 km mainly eastwards, passing through ten states (Germany, Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova and Ukraine) and four European capitals (Vienna, Bratislava, Budapest and Belgrade) with embouchure in the west coasts of the Black Sea via the Danube Delta, mainly in Romania. Danube played a profound role in the European political, social, economic and cultural history influencing in a multifold manner the heritage of many European nations, some of those without even a physical connection with the River, as it is the case of the Greeks, to whom the Danube is a reference to their own 18th century Enlightenment movement. Due to Danube’s important role in History, the extensive emphasis to its cartographic depiction was obviously a conditio sine qua non especially in the 17th and 18th century European cartography. In this paper, taking advantage of the modern digital technologies as applied in the recently established domain of cartographic heritage, two important and historically significant 18th century maps of the Danube are comparatively discussed in view also to the reference possibilities available today in relevant studies by the digital maps offered by powerful providers as e.g. -

The Reception of Isaac Newton in Europe

The Reception of I THE RECEPTION OF ISAAC NEWTON IN EUROPE LANGUAGE COMMUNITIES, REGIONS AND COUNTRIES: THE GEOGRAPHY OF NEWTONIANISM Edited by Helmut Pulte and Scott Mandelbrote BLOOMSBURY ACADEM I C LO:-IDON • NEW YORK• OXt"ORD • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Pie 50 Bedford Square, London, WC 1B 3DP. UK 1385 Broadway, NewYork, NY 10018, USA BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Pie First published in Great Britain 2019 Reprinted in 2019 Copyright© Helmut Pulte, Scott Mandelbrote and Contributors, 2019 Helmut Pulte, Scott Mandelbrote and Contributors have asserted their rights under the Copyright. Designs and Pat~nts Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgements on pp. xv, 199 constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design: Eleanor Rose All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Bloomsbury Publishing Pie does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. -

The Anatomy in Greek Iatrosophia During the Ottoman Domination

JBUON 2021; 26(1): 33-38 ISSN: 1107-0625, online ISSN: 2241-6293 • www.jbuon.com Email: [email protected] REVIEW ARTICLE The Anatomy in Greek Iatrosophia during the Ottoman domination era Christos Tsagkaris1, Ioannis Koliarakis1, Agamemnon Tselikas2, Markos Sgantzos3, Ioannis Mouzas4, John Tsiaoussis1,4 1Laboratory of Anatomy, Medical School, University of Crete, 70013 Heraklion, Greece. 2Centre for History and Palaeography, Cultural Foundation of the National Bank of Greece, 10558 Athens, Greece. 3Laboratory of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, School of Health Sciences, University of Thessaly, 41334 Larissa, Greece. 4Medical Museum, Medical School, University of Crete, 71500 Heraklion, Greece. Summary The knowledge of Anatomy during the Ottoman domination tomans. At the same time, anatomy has been discussed by in Greece has not been widely studied. Medical knowledge of various authors in diverse contexts. All in all, it appears the time can be retrieved from folk and erudite books called that a consensus on the importance of anatomy has been Iatrosophia. The majority of these books focused on empirical established among Greek scholars in the late 18th century, diagnostics and therapeutics. However, a small quota of these leading to the translation of current anatomical knowledge Iatrosophia includes important information about anatomy. to the contemporary language and literature. The interest in anatomy appears only after the Neohellenic Enlightenment (1750-1821) and has been associated to the Key words: anatomy, history of medicine, Iatrosophia, Neo- scholarly background of the 1821 revolution against the Ot- hellenic Enlightenment Introduction Medicine in Greece during the Ottoman domi- During Ottoman domination, Iatrosophia per- nation has not been widely studied. -

The Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece

e-Perimetron , Vol. 3, No. 3, 2008 [101-119] www.e-perimetron.org | ISSN 1790-3769 George Tolias * Antiquarianism, Patriotism and Empire. Transfer of the cartography of the Travels of Anacharsis the Younger , 1788-1811 Keywords : Late Enlightenment; Antiquarian cartography of Greece; Abbé Barthélemy; Anacharsis; Barbié du Bocage ; Guillaume Delisle; Rigas Velestinlis Charta. Summary The aim of this paper is to present an instance of cultural transfer within the field of late Enlightenment antiquarian cartography of Greece, examining a series of maps printed in French and Greek, in Paris and Vienna, between 1788 and 1811 and related to Abbé Barthé- lemy’s Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece . The case-study allows analysing the al- terations of the content of the work and the changes of its symbolic functions, alterations due first to the transferral of medium (from a textual description to a cartographic representation) and next, to the successive transfers of the work in diverse cultural environments. The trans- fer process makes it possible to investigate some aspects of the interplay of classical studies, antiquarian erudition and politics as a form of interaction between the French and the Greek culture of the period. ‘The eye of History’ The Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece , by Abbé Jean-Jacques Barthélemy (1716- 1795) 1, was published on the eve of the French Revolution (1788) and had a manifest effect on its public. “In those days”, the Perpetual Secretary of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, Bon-Joseph Dacier (1742-1833) was to recall in 1826, “an unexpected sight came to impress and surprise our spirit. -

The Anthimos Gazis World Map in Kozani

e-Perimetron , Vol. 3, No. 2, 2008 [95-100] www.e-perimetron.org | ISSN 1790-3769 Evangelos Livieratos ∗ The Anthimos Gazis world map in Kozani Keywords: Anthimos Gazis; 18 th century cartography; world maps; rare maps; Greek cartography; Greek Enlightenment. Summary The rare large dimensions world map by the Greek scholar Anthimos Gazis (1758- 1828) published in four sheets, Vienna 1800, was recently identified at the Municipal Library of the city of Kozani, Greece. The map in an advanced state of deterioration was carefully restored and will be part of the map collection of the newly established Municipal Map Library of Kozani. In this note a short description of the map is car- ried out in the context of its cartographic typology and its role to the case of Greek Enlightenment. Introduction Anthimos Gazis 1 (1758-1828) from Mēlies in Mount Pēlion, Thessaly, is a known scholar of the Greek Enlightenment 2 active in the late 18 th and early 19 th century. Among his early contributions, for the case of education and cultural revival of Greeks in the eve of the Greek War of Independence (1821-1828), the publication of his geography books and maps is worth mentioning. Gazis’ editorial initiatives are developed during his servicing as parish priest at the Greek-Orthodox church of St George in Vienna, the city where his coetaneous Rigas Velestinlis, also from Thessaly, published his famous Charta in twelve sheets only three years before (1797) 3. Actually, the Anthimos Gazis map of Greece 4 in four sheets (Vienna 1800) is considered as inspired (even as derived) from Rigas Charta, both engraved by Franz Müller. -

Περίληψη : Nikolaos Koumbaros Or Skoufas Was Born in Komboti, Arta

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Ανεμοδουρά Μαρία Μετάφραση : Πανουργιά Κλειώ Για παραπομπή : Ανεμοδουρά Μαρία , "Nikolaos Skoufas", Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Εύξεινος Πόντος URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=11571> Περίληψη : Nikolaos Koumbaros or Skoufas was born in Komboti, Arta. Initially he was a cap-maker. He immigrated to Russia were he became a merchant. He was one of the founders of the Filiki Etaireia. He died of heart disease in Constantinople. Άλλα Ονόματα Nikolaos Koumbaros Τόπος και Χρόνος Γέννησης 1779 – Komboki, Arta Τόπος και Χρόνος Θανάτου 1818 – Constantinople Κύρια Ιδιότητα Merchant, one of the founders of the Filiki Etaireia. 1. Birth – early years Nikolaos Koumbaros or Skoufas was born in 1779 in Komboti, Arta, to a middle-class family. He was initially taught by the ascetic Theocharis Ntouia in Arta in the ruined church of Kassopetria.1 He was later taught by Dendramis (or Ventramis) Mesologgitis.2 After turning 18, Nikolaos moved to Arta were he became a cap-maker (hence his nick-name Skoufas) (skoufos = cap) and also ran a small shop. In 1813 he immigrated to Russia on the quest for a better life. He settled in Odessa, the newly-established Black Sea port-town and became a merchant. 2. The foundation of the Etaireia and Skoufas’activities as a Filikos In Odessa, Skoufas met other merchants who were fellow countrymen, among them the future co-founders of the Filiki EtaireiaAthanasios Tsakalof and Emmanuil Xanthos, and Constantinos Rados. Constantinos Rados, who later participated actively in the Revolution, had studied in Pisa in Italy where he had become associated with Carbonari movement. -

93323765-Mack-Ridge-Language-And

Language and National Identity in Greece 1766–1976 This page intentionally left blank Language and National Identity in Greece 1766–1976 PETER MACKRIDGE 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Peter Mackridge 2009 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mackridge, Peter. -

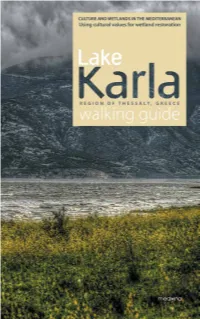

ENG-Karla-Web-Extra-Low.Pdf

231 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration 2 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration Lake Karla walking guide Mediterranean Institute for Nature and Anthropos Med-INA, Athens 2014 3 Edited by Stefanos Dodouras, Irini Lyratzaki and Thymio Papayannis Contributors: Charalampos Alexandrou, Chairman of Kerasia Cultural Association Maria Chamoglou, Ichthyologist, Managing Authority of the Eco-Development Area of Karla-Mavrovouni-Kefalovryso-Velestino Antonia Chasioti, Chairwoman of the Local Council of Kerasia Stefanos Dodouras, Sustainability Consultant PhD, Med-INA Andromachi Economou, Senior Researcher, Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens Vana Georgala, Architect-Planner, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Ifigeneia Kagkalou, Dr of Biology, Polytechnic School, Department of Civil Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace Vasilis Kanakoudis, Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Thessaly Thanos Kastritis, Conservation Manager, Hellenic Ornithological Society Irini Lyratzaki, Anthropologist, Med-INA Maria Magaliou-Pallikari, Forester, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Sofia Margoni, Geomorphologist PhD, School of Engineering, University of Thessaly Antikleia Moudrea-Agrafioti, Archaeologist, Department of History, Archaeology and Social Anthropology, University of Thessaly Triantafyllos Papaioannou, Chairman of the Local Council of Kanalia Aikaterini Polymerou-Kamilaki, Director of the Hellenic Folklore Research -

Περίληψη : Γενικές Πληροφορίες Area: 84.069 Km2

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Κέκου Εύα , Σπυροπούλου Βάσω Μετάφραση : Easthope Christine , Easthope Christine , Ντοβλέτης Ονούφριος (23/3/2007) Για παραπομπή : Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Κέκου Εύα , Σπυροπούλου Βάσω , "Syros", 2007, Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Περίληψη : Γενικές Πληροφορίες Area: 84.069 km2 Coastline length: 84 km Population: 19,782 Island capital and its population: Hermoupolis (11,799) Administrative structure: Region of South Aegean, Prefecture of the Cyclades, Municipality of Hermoupolis (Capital: Hermoupolis, 11,799), Municipality of Ano Syros (Capital: Ano Syros, 1,109), Municipality of Poseidonia (Capital: Poseidonia, 633) Local newspapers: Koini Gnomi, Logos, Apopsi Local journals and magazines: Serious Local radio stations: Media 92 (92.0), Radio Station of the Metropolis of Syros (95.4), Aigaio FM (95.4), Syros FM 100.3 (100.3), FM 1 (101.0), Faros FM (104.0), Super FM (107.0) Local TV stations: Syros TV1, Aigaio TV Museums: Syros Archaeological Museum, Historical Archive (General State Archives), Art Gallery "Hermoupolis", Hermoupolis Municipal Library, Cyclades Art Gallery, Industrial Museum of Syros, Historical Centre of the Catholic Church of Syros, Historical Archive of the Municipality of Ano Syros, Marcos Vamvakaris Museum, Ano Syros Museum of Traditional Professions Archaeological sites and monuments: Chalandriani, Kastri, Grammata, Miaoulis Square at Hermoupolis, Hermoupolis Town Hall, Hellas -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Ὑγίαινε, φίλον ἦτορ!“ Stilistische Untersuchungen zur neugriechischen Epistolographie anhand der Briefe von Konstantinos M. Koumas Verfasserin Anna Ransmayr angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2008 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 383 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Byzantinistik und Neogräzistik Betreuerin: Univ. - Prof. Dr. Maria A. Stassinopoulou INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Danksagung ............................................................................................................ 4 Einleitung ............................................................................................................... 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis ......................................................................................... 8 1. Kurze Geschichte der griechischen Epistolographie ..................................... 9 1.1. Griechische Briefe in Antike und byzantinischer Zeit................................. 9 1.1.1. Antike.................................................................................................... 9 1.1.2. Byzantinische Zeit............................................................................... 10 1.1.3. Brieftheorie und Briefgestaltung......................................................... 11 1.2. Griechische Briefe in der frühen Neuzeit (bis 1821) ................................. 16 1.2.1. Wichtige Epistolographen................................................................... 16 1.2.2. Briefsteller.......................................................................................... -

159 Various Finds Either Still in Situ Or at the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, As Well As His Own Research Carried in This Region

Book Reviews 159 various finds either still in situ or at the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, as well as his own research carried in this region. In the Introduction (pp. 1-4), it is stated that in comparing the research work on the Bosphorus, concerning the ancient period with the Byzantine one, it becomes evident that there is much to be desired for the latter. Accordingly the author proceeds to the analysis of sources, reference books (pp. 5-12), and gives an historical background (pp. 14-15), on the Straits of Bosphorus. Examining the European shore from Galata to the Black Sea (pp. 15-48), the author enumerates monasteries, churches, summer palaces etc., as well as architectural remains and tries to identify the sites mentioned in the Byzantine texts with modem place-names. He discusses also the opinions of various authors and brings forth his own conclusions. In the same way he examines the Asiatic shore starting from Skoutari up to the Black Sea. In (pp. 72-93) he discusses at length the Byzantine fort “Ιερόν” (Yoros Kalesi) situ ated in the military zone of Bosphorus, correcting mistakes of previous authors and pointing out certain obscure parts in the history of this fort. Consequently, in his epilogue (pp. ΙΟΒ Ι 12), the author evaluates the research work up to the present and emphasizes the lack of information for A thorough study on the subject. Also he brings to the attention of the reader the points which should be investigated better for A future broader study. This is in short the content of Professor Eyice’s book. -

Filiki Etaireia: the Rise of a Secret Society in the Making of the Greek Revolution

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Filiki Etaireia: The rise of a secret society in the making of the Greek revolution Nicholas Michael Rimikis Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the European History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Rimikis, Nicholas Michael, "Filiki Etaireia: The rise of a secret society in the making of the Greek revolution" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 317. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/317 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Filiki Etaireia: The Rise of a Secret Society in the making of the Greek revolution Senior project submitted to the division of social studies of Bard College Nicholas Rimikis Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2017 A note on translation This project discusses the origins of the Greek war of independence, and thus the greater part of the source material used, has been written in the Greek language.