The Age-Productivity Gradient: Evidence from a Sample of F1 Drivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eddie Irvine During a Pullcd Her Even Before He Got in the Car," Is Prone to Chaotic Personal Disorganisation, Lunch Brcak at Mugello

--!-'-4-:--^a+:r- -;*r4i .:rii" i:,:.i,_ STYLED BY REBECCA LEARY BY TOMMY HILFIGER CLOTHES 4il Jr r) J HEgAN HAVEA'.IYGIRL HEWANIS. HE HASA NEtiI, 85 MlLLlOl,l CONTRACI r W]IH JAGUAR AND HE r DRRIES A RED FERRARI... ED PHOTOGRAPHS BY DAN BURN-FORfl : h rI :,:t:'_Sk*rlE!r{ir-.. r:r ffi than 1 5. The-v giggle and smooth dolvn the ir hair in girlish embarrassment, pretending not to notice that Irvine is addressing them. ".{';ete niente tla fare?" he shouts, after getting no response. Having lived in Italy' for most ofthe past four years, Irvine speaks passable Italian and conducts interviervs with tl're Italian media in their native lan- guage. He gets little reaction from asking "Nothing else to do?" other than blushes and hip-su,ivelling glances away. I-ater, horvever, the gir'ls loiteroutside his Ferrari motorhome, and are introduced to Irline br their uncle, the r.ice-dilector of track securitr . He informs Irvine that thev are here for him, that they adore him, and think he is verr good-looling. The girls don't know what to do with themselr'es. I suggest a photo with Eddie and he obliges. Thel stand bolt upright r'vith a look of shock on their faces. Dan, the Esquire photographer, encourages In'ine to put his arms around the girls and he cud- dles them close. "OK, that's enough," he calls out. "You'll get me arrested." Eddie lrvine behaves how we expect our racing drivers to behave: like rac- ing der i1s. -

Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2 Tuesday 14 May 2013 10:30

Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2 Tuesday 14 May 2013 10:30 Graham Budd Auctions Ltd Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Graham Budd Auctions Ltd (Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 335 restrictions and 144 meetings were held between Easter 1940 Two framed 1929 sets of Dirt Track Racing cigarette cards, and VE Day 1945. 'Thrills of the Dirt Track', a complete photographic set of 16 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 given with Champion and Triumph cigarettes, each card individually dated between April and June 1929, mounted, framed and glazed, 38 by 46cm., 15 by 18in., 'Famous Dirt Lot: 338 Tack Riders', an illustrated colour set of 25 given with Ogden's Post-war 1940s-50s speedway journals and programmes, Cigarettes, each card featuring the portrait and signature of a including three 1947 issues of The Broadsider, three 1947-48 successful 1928 rider, mounted, framed and glazed, 33 by Speedway Reporter, nine 1949-50 Speedway Echo, seventy 48cm., 13 by 19in., plus 'Speedway Riders', a similar late- three 1947-1955 Speedway Gazette, eight 8 b&w speedway 1930s illustrated colour set of 50 given with Player's Cigarettes, press photos; plus many F.I.M. World Rider Championship mounted, framed and glazed, 51 by 56cm., 20 by 22in.; sold programmes 1948-82, including overseas events, eight with three small enamelled metal speedway supporters club pin England v. Australia tests 1948-53, over seventy 1947-1956 badges for the New Cross, Wembley and West Ham teams and Wembley -

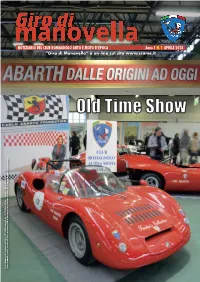

Old Time Show

Poste Italiane S.p.A. Spedizione in A.P. D.L. 353/2003 (convertito in L. 27/02/04 n. 46) art. 1 comma 1 - Aut. n. 0033/RA In caso di mancato recapito restituire all’ufficio accettazione CDM di Ravenna per la restituzione al mittente che si impegna a pagare la relativa tariffa. N O T I Z I A R I O D E L C L “ U G B i R r O o M d A G i N M O a L O n A o U v O T e O l l E a M ” l O è T d O o D n ’ E - P l O i n C T e A s u i l s m i t o w w e w . c r a m S A n e n o . i 1 t h N . 1 A o P R I L E w 2 0 1 8 Calendario manifestazioni 2018 VI ASPETTIAMO! NOTIZIARIO DEL CLUB ROMAGNOLO AUTO E MOTO D’EPOCA Anno1 N.1 APRILE 2018 “Giro di Manovella” è on-line sul sito www.crame.it Old Time Show . a f f i r a t a v i t a l e r a l e r a g a p a a n g e p m i . i O s B - e B h c C D e - t 1 n e a t t i m m m l o c a 1 e n . t o i r z a u ) t i 6 t 4 s e . -

PDF Download

NEW Press Information Coburg, December 10th, 2010 NEW 2 The legend returns. The NEW STRATOS will be officially presented on 29./30.11.2010, at the Paul Ricard Circuit in Le Castellet. The legendary Lancia Stratos HF was without a doubt the most spectacular and successful rally car of the 70s. With its thrilling lines and uncompro- mising design tailored to rally use, the Stratos not only single-handedly rewrote the history of rallying, it won a permanent place in the hearts of its countless fans with its dramatic performance on the world’s asphalt and gravel tracks – a performance which included three successive world championship titles. For Michael Stoschek, a collector and driver of historic racing cars, as well as a successful entrepreneur in the automotive supply industry, the development and construction of a modern version of the Stratos represents the fulfillment of a long-held dream. Back in 2003, the dream had already begun to take on a concrete form; now, at last, it has become a reality: In November 2010, forty years after the Stratos’ presentation at the Turin Motor Show, the New Stratos will be publicly presented for the first time at the Paul Ricard Circuit. The legend returns. NEW 3 A retrospective. It all began in 1970, at the Turin exhibition stand of the automobile designer, Bertone. The extreme Stratos study on display there – a stylistic masterpiece by the designer Marcello Gandini – didn’t just excite visitors, but caught the attention of Cesare Fiorio, Lancia’s team manager at the time… and refused to let go. -

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors' Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London VIEWING Please note that bids should be ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES submitted no later than 16.00 Wednesday 9 December Motor Cars Monday to Friday 08:30 - 18:00 on Wednesday 9 December. 10.00 - 17.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Thereafter bids should be sent Thursday 10 December +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax directly to the Bonhams office at from 9.00 [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder the sale venue. information including after-sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax or SALE TIMES Motorcycles collection and shipment [email protected] Automobilia 11.00 +44 (0) 20 8963 2817 Motorcycles 13.00 [email protected] Please see back of catalogue We regret that we are unable to Motor Cars 14.00 for important notice to bidders accept telephone bids for lots with Automobilia a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 8700 273 618 SALE NUMBER Absentee bids will be accepted. ILLUSTRATIONS +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax 22705 New bidders must also provide Front cover: [email protected] proof of identity when submitting Lot 351 CATALOGUE bids. Failure to do so may result Back cover: in your bids not being processed. ENQUIRIES ON VIEW Lots 303, 304, 305, 306 £30.00 + p&p AND SALE DAYS (admits two) +44 (0) 8700 270 090 Live online bidding is IMPORTANT INFORMATION available for this sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax BIDS The United States Government Please email [email protected] has banned the import of ivory +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 with “Live bidding” in the subject into the USA. -

1911: All 40 Starters

INDIANAPOLIS 500 – ROOKIES BY YEAR 1911: All 40 starters 1912: (8) Bert Dingley, Joe Horan, Johnny Jenkins, Billy Liesaw, Joe Matson, Len Ormsby, Eddie Rickenbacker, Len Zengel 1913: (10) George Clark, Robert Evans, Jules Goux, Albert Guyot, Willie Haupt, Don Herr, Joe Nikrent, Theodore Pilette, Vincenzo Trucco, Paul Zuccarelli 1914: (15) George Boillot, S.F. Brock, Billy Carlson, Billy Chandler, Jean Chassagne, Josef Christiaens, Earl Cooper, Arthur Duray, Ernst Friedrich, Ray Gilhooly, Charles Keene, Art Klein, George Mason, Barney Oldfield, Rene Thomas 1915: (13) Tom Alley, George Babcock, Louis Chevrolet, Joe Cooper, C.C. Cox, John DePalma, George Hill, Johnny Mais, Eddie O’Donnell, Tom Orr, Jean Porporato, Dario Resta, Noel Van Raalte 1916: (8) Wilbur D’Alene, Jules DeVigne, Aldo Franchi, Ora Haibe, Pete Henderson, Art Johnson, Dave Lewis, Tom Rooney 1919: (19) Paul Bablot, Andre Boillot, Joe Boyer, W.W. Brown, Gaston Chevrolet, Cliff Durant, Denny Hickey, Kurt Hitke, Ray Howard, Charles Kirkpatrick, Louis LeCocq, J.J. McCoy, Tommy Milton, Roscoe Sarles, Elmer Shannon, Arthur Thurman, Omar Toft, Ira Vail, Louis Wagner 1920: (4) John Boling, Bennett Hill, Jimmy Murphy, Joe Thomas 1921: (6) Riley Brett, Jules Ellingboe, Louis Fontaine, Percy Ford, Eddie Miller, C.W. Van Ranst 1922: (11) E.G. “Cannonball” Baker, L.L. Corum, Jack Curtner, Peter DePaolo, Leon Duray, Frank Elliott, I.P Fetterman, Harry Hartz, Douglas Hawkes, Glenn Howard, Jerry Wonderlich 1923: (10) Martin de Alzaga, Prince de Cystria, Pierre de Viscaya, Harlan Fengler, Christian Lautenschlager, Wade Morton, Raoul Riganti, Max Sailer, Christian Werner, Count Louis Zborowski 1924: (7) Ernie Ansterburg, Fred Comer, Fred Harder, Bill Hunt, Bob McDonogh, Alfred E. -

Forgotten F1 Teams – Series 1 Omnibus Simtek Grand Prix

Forgotten F1 Teams – Series 1 Omnibus Welcome to Forgotten F1 Teams – a mini series from Sidepodcast. These shows were originally released over seven consecutive days But are now gathered together in this omniBus edition. Simtek Grand Prix You’re listening to Sidepodcast, and this is the latest mini‐series: Forgotten F1 Teams. I think it’s proBaBly self explanatory But this is a series dedicated to profiling some of the forgotten teams. Forget aBout your Ferrari’s and your McLaren’s, what aBout those who didn’t make such an impact on the sport, But still have a story to tell? Those are the ones you’ll hear today. Thanks should go to Scott Woodwiss for suggesting the topic, and the teams, and we’ll dive right in with Simtek Grand Prix. Simtek Grand Prix was Born from Simtek Research Ltd, the name standing for Simulation Technology. The company founders were Nick Wirth and Max Mosley, Both of whom had serious pedigree within motorsport. Mosley had Been a team owner Before with March, and Wirth was a mechanical engineering student who was snapped up By March as an aerodynamicist, working underneath Adrian Newey. When March was sold to Leyton House, Mosley and Wirth? Both decided to leave, and joined forces to create Simtek. Originally, the company had a single office in Wirth’s house, But it was soon oBvious they needed a Bigger, more wind‐tunnel shaped Base, which they Built in Oxfordshire. Mosley had the connections that meant racing teams from all over the gloBe were interested in using their research technologies, But while keeping the clients satisfied, Simtek Began designing an F1 car for BMW in secret. -

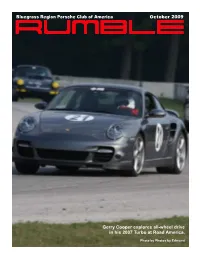

October 2009

RUMBLEBluegrass Region Porsche Club of America October 2009 Gerry Cooper explores all-wheel drive in his 2007 Turbo at Road America. Photo by Photos by Edmund http:// bgs.pca.org RUMBLE October 2009 Vol. 7 No. 7 Table of Contents 4 President’s Message By Gary Hackney 10 Sep. 12th Cars & Coffee 4 Editor’s Notes 11 Four Roses Distillery Drive Photo Essay 5 Club Officers 13 Born to be Wild By Paul Elwyn 6 Board Minutes By William Glover 15 Parade Group Photo 6 Membership News By Tim McNeely 16 Road America Revisited By Gerry Cooper 7 Calendar of Events By Mark Doerr 20 Petit Lemans Photo Essay by Ken Partymiller 8 Within the Zone 13 By Ken Hold 25 Louisville Concours d’Elegance 9 Covered Bridge Drive By Ed Steverson 36 Porsche in Formula 1 By Ken Partymiller Cover photo by Photos by Edmund ADVERTISERS HOW TO ADVERTISE To advertise in RUMBLE visit bgs.pca.org 2 Porsche of Lexington to download a form. 15 James W. Wilson Consulting 38 Stuttgart Motors, Inc. Advertising rates: 38 Paul’s Foreign Auto Quarter Page $15/month, $120/year; 39 Motorsports of Lexington, LTD. Half Page $30/month, $240/year; 39 ABRACADABRA graphics Full Page $60/month/$400/year. 40 Porsche of Lexington Classified Ads are free to members, free to anyone for Porsche-related items, $15/month for non-Porsche items. Paul Elwyn, Editor 821 Pecos Circle, Danville, KY 40422 [email protected] RUMBLE, published monthly and distributed via electronic means, is the official publication of the Bluegrass Region, Zone 13, Porsche Club of America, Inc., a non-profit organization registered in the state of Kentucky. -

La Dallara E La Motor Valley 27 Ottobre 2018 Products and Services

La Dallara e la Motor Valley 27 ottobre 2018 Products and Services Design, developingDesign, developing and manufacturing and manufacturing racing racing cars cars F2,F2, GP3,GP3, F3,F3, GrandGrand--AmAm,, IndyCarIndyCar,, IndyIndyLightsLights,, FormulinoFormulino VW,VW, WorldWorld Series by Renault,Series Sports by Car, Renault, FE… Sports Car, FE… ConsultingConsulting to to manufacturing manufacturing firms firms of racing of racing cars cars Audi,Audi, Ferrari, Ferrari, Honda, Honda, Lamborghini,Lamborghini, Lotus, Maserati, Porsche,Porsche, Toyota,Toyota, FormulaFormula 1. 1. ConsultingConsulting to to manufacturing manufacturing firms firms of high of performancehigh performance road cars road cars Alfa Romeo, Bugatti, Ktm, ecc. Alfa Romeo, Bugatti, Ktm, ecc. Products and Services – Dallara Stradale TRANSFORMATION Group History 2007 - 2018 CONSOLIDATION 1998-2007 Organization DEVELOPMENT approx. 670 employees 1985-1997 Organization START –UP approx. 100 employees 1972 - 1984 Organization Company Premises approx. 30 employees Wind Tunnel IT - 08 Organization Company Premises Profess. Simul. I T -10 Expanding production site 4 employees Company Premises New factory USA -12 Profess. Simul. USA -14 New offices and Technology production site (1991) DARC IT – 16 Company Premises Expanding the knowledge New factory IT - 17 “garage”, then small of carbon fiber Technology applications and factory (a) 1.st chassis in carbon Capital expenditure aerodynamics and vehicle c.a. 20 MEuro applied R&D fiber dynamics (b) Aero development – c.a. 18 MEuro Capex Technology -1st Wind Tunnel with Sales Turnover First use of carbon fiber moving carpet (84) Sales Turnover material in chassis Export market share 55% cars and spare parts, 45% -2nd Wind Tunnel (95) overtakes domestic Engineering consulting. -

Media Information

PR Document 2020 Japanese Super Formula Championship Series Media Information August 27 2020 1 Super Formula : Then and Now In the 1950s, the Fédération Internationale de I’Automobile (FIA) launched the Drivers’ Championship to find the world’s fastest formula car drivers the purest form of racing machine. That ethos was passed on to all FIA national member organizations.Top-level formula motor racing has been held in Japan in various forms since 1973, when Formula 2000 was first launched. The competition evolved into Formula Two in 1978 and then Formula 3000 in 1987. Japan Race Promotion, Inc. (JRP) was established in 1995 and continued carrying the competition torch in 1996 under the name of Formula Nippon. In 2013, the name of the competition was changed again to Japanese Championship Super Formula and a bold plan was implemented to upgrade the race cars and lift the profile of the competition with the clear aim of spreading the appeal of Super Formula from Japan to other parts of Asia. Another hope was to turn the series into a third great open-wheel racing competition to go along with Formula One and IndyCar. The competition’s name was changed again in 2016 to Japanese Super Formula Championship. In 2017, BS Fuji began broadcasting live Super Formula races, giving many motorsport fans the chance to watch championship races on free-to-air television. In the early days, formula racing in Japan was led by top drivers such as Kunimitsu Takahashi, Kazuyoshi Hoshino and Satoru Nakajima, who later competed on the global stage in Formula One. -

1991 Primer Gran Premio De México 1991 LA FICHA

1991 Primer Gran Premio de México 1991 LA FICHA GP DE MÉXICO XV GRAN PREMIO DE MÉXICO Sexta carrera del año 16 de junio de 1991 En el “Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez”. Distrito Federal (carrera # 506 de la historia) Con 67* laps de 4,421 m., para un total de 296.207 Km [*Reducida en 2 giros, por largada en falso] Podio: 1- Riccardo Patrese/ Williams 2- Nigel Mansell/ Williams 3- Ayrton Senna/ McLaren Crono del ganador: 1h 29m 52.205s a 197.757 Kph/ prom (Grid: 1º) 10* puntos [*A partir de este año, el primer lugar recibirá: 10 puntos] Vuelta + Rápida: Nigel Mansell/ Williams (la 61ª) de 1m 16.788s a 207.267 Kph/ prom Líderes: Mansell/ Williams (de la 1 a la 14) y, Patrese/ Williams (de la 15 a la 67) Pole position: Riccardo Patrese/ Williams-Renault 1m 16.696s a 207.515 Kph/ prom Pista: seca POR REGLAMENTO Los autos no deben de pesar menos de 505 Kg Tipo de motores: con pistones alternativos de 4 tiempos Sobrealimentación: prohibida Capacidad máxima: 3.5 lt Número de clindros: no más de 12 RPM: ilimitada Clase de gasolina: ilimitada Reabastecimiento en la carrera: prohibido Consumo máximo: ilimitado INSCRITOS # PILOTO NAC EQUIPO FONDO P # MOTOR CIL NEUM RA121E V-12 3.5 1 AYRTON SENNA BRA Honda Marlboro McLaren McLaren MP4/6 Honda Goodyear litros 2 GERHARD BERGER AUT Honda Marlboro McLaren McLaren MP4/6 Honda RA121E V-12 3.5 Goodyear 3 SATORU NAKAJIMA JAP Braun Tyrrell Honda Tyrrell 020 Honda RA101E V-10 3.5 Pirelli 4 STEFANO MODENA ITA Braun Tyrrell Honda Tyrrell 020 Honda RA101E V-10 3.5 Pirelli 5 NIGEL MANSELL ING Canon Williams Team -

GP BELGIO Rosberg a Spa Getta La Maschera E Fa Fuori Hamilton Con Una Mossa

n. 283 25 agosto 2014 STAR WARS GP BELGIO Rosberg a Spa getta la maschera e fa fuori Hamilton con una mossa... alla Hamilton. Ormai è guerra aperta fra le due stelle della Mercedes: Lauda e il team come reagiranno? Registrazione al tribunale Civile di Bologna con il numero 4/06 del 30/04/2003 Direttore responsabile: Massimo Costa ([email protected]) Redazione: Stefano Semeraro Marco Minghetti Collaborano: Carlo Baffi Antonio Caruccio Marco Cortesi Alfredo Filippone Dario Lucchese Claudio Pilia Guido Rancati Dario Sala Silvano Taormina Filippo Zanier Tecnica: Paolo D’Alessio Produzione: Marco Marelli © Tutti gli articoli e le immagini Fotografie: contenuti nel Magazine Italiaracing Photo4 sono da intendersi Actualfoto a riproduzione riservata Photo Pellegrini ai sensi dell'Art. 7 R.D. 18 maggio 1942 n.1369 MorAle Realizzazione: Inpagina srl Via Giambologna, 2 40138 Bologna Tel. 051 6013841 Fax 051 5880321 [email protected] 2 Il graffio di Baffi FORMULA 1 GP BELGIO PANICO 4 MERCEDES Una probabilissima ennesima doppietta per la Casa di Stoccarda va in fumo a causa di una manovra scellerata di Rosberg al secondo giro. Wolff minaccia punizioni per il tedesco che però nel Mondiale è tornato avanti di 29 lunghezze e ormai non sembra più interessato a ricucire il rapporto con Hamilton 5 FORMULA 1 GP BELGIO Filippo Zanier non avrebbe ceduto la linea". Al di là di que- HAMILTON ACCUSA: sto, però, per il tedesco arriva comunque la Doveva essere una cavalcata inarrestabile, L’HA FATTO APPOSTA condanna: "In ogni caso, voluto o no, per dopo i due secondi rifilati ai rivali più vici- noi resta inaccettabile.