Forgotten F1 Teams – Series 1 Omnibus Simtek Grand Prix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INHALT MOTOR KLASSIK IM GRATIS-TEST Kostenlose Leseprobe

INHALT MOTOR KLASSIK IM GRATIS-TEST Kostenlose Leseprobe. Die neue Motor Klassik jetzt testen: 2 Ausgaben kostenlos. 2 Ausgaben DER GRATIS-TEST VON MOTOR KLASSIK: GRATIS 2 Ausgaben Motor Klassik GRATIS testen Wenn Sie anschließend weiterlesen möchten: 7% Preisvorteil gegenüber Einzelkauf Das Jaguar-Modell als Treuegeschenk, wenn Sie den Testbezug verlängern Jaguar E-Type als Treue- geschenk DIE NEUE MOTOR KLASSIK IHR TREUEGESCHENK Die ganze Welt der klassischen Automobile: Fahrberichte, Die Ikone der Swinging Sixties: der Jaguar E-Type Kaufberatung, Technik und Szene. Jeden Monat neu in Motor Klassik. als detailiertes 1:18 Diecast-Modell von Bburago. 787730 Name, Vorname JA, ICH MÖCHTE DIE NEUE MOTOR KLASSIK GRATIS TESTEN. Bitte schicken Sie mir die nächsten 2 Ausgaben von Motor Klassik Viele weitere GRATIS zum Test. Falls ich Motor Klassik nach dem Test nicht wei- attraktive Angebote: Straße, Nr. terbeziehen möchte, sage ich spätestens 14 Tage nach Erhalt der 2. www.motor-klassik.de/abo Ausgabe einfach ab. Ansonsten bekomme ich Motor Klassik weiter- hin monatlich mit über 7% Ersparnis zum Jahrespreis von z.Zt. nur 49,90 € (A: 56,60 €; CH: 102,– SFr.) frei Haus und GRATIS dazu das PLZ Ort Motor Klassik Jaguar-Modell als Treuegeschenk. Dieser Folgebezug kann nach Abo-Service Ablauf des Bezugszeitraums jederzeit abbestellt werden. 70138 Stuttgart Ja , ich möchte in Zukunft den kostenlosen Newsletter von Motor Klassik erhalten. Telefon E-Mail [email protected] Ja, ich bin damit einverstanden, dass Motor Klassik und die Motor Presse Stuttgart +49 (0) 1805 354050-2556* mich künftig per Telefon oder E-Mail über interessante Angebote informieren. +49 (0) 1805 354050-2550* Datum/Unterschrift zur Bestellbestätigung Verlagsgarantie: Ihre Bestellung kann innerhalb von 15 Tagen ohne Angabe von Gründen in Textform widerrufen werden bei: Motor Klassik Aboservice, 70138 Stuttgart oder www.webaboshop.de. -

Books for Sale Title Author Price $ a History of the Rob Roy Hill

Books for Sale Title Author Price $ A History of the Rob Roy Hill Climb Leon Sims 45 Australian Cars & motoring John Goode 10 Boxer [ Ferrari } Jonathon Thompson 40 Cars of the 30s & 40s Michael Sedgewick 40 Cars Cars Cars Cars Sydney Charles Haughton Davis 10 Cooper Cars Doug Nye 60 Driving Ambition Alan Jones , Keith Botsford 15 Ferrari Godfrey Eaton 20 Ferrari [Great Marques ] Godfrey Eaton 10 From Redex to Repco Bill Tuckey , T.B. Floyd 40 Gardner a dream come true Nick Hartgerink 15 Grand Prix 1985 F1 World Championship Nigel Roebuck 25 Porsche Grand Marques Chris Harvey 10 Holden vs Ford the cars ,culture & competition Steve Bedwell 20 Lex Davison – Larger than life Graham Howard 50 Murray Walker Unless I ‘m very much mistaken Murray Walker 10 Raceyear 1984 Gary Sparke 15 Raceyear 1985 Gary Sparke 15 Racing Cars Racing Cars Richard Hough 15 The exciting world of Jackie Stewart Jackie Stewart 12 The Great Cars Ralph Stein 18 The Great Racing Cars & Drivers Charles Fox 15 The History of Motor Racing William Body , Brian Laban 10 The Power & the Glory A century of Motor Racing Ivan Rendall 10 The Racing Car Cecil Clutton , Cyrin Posthumus , Denis Jenkinson 15 The Vintage Motor Car C Clutton , J Stanford 10 Champion Year Mike Hawthorn 25 All Colour Book of Racing Cars Brad King 10 Racing Cars & the history of Motor Sport Peter Roberts 20 Porsche Michael Colton 20 Ferrari – The Grand Prix Cars Alan Henry 20 The Crown of the Road Susan Priestly 5 Motor Racing The Australian Way Brian Hanrahan 30 Allan Moffat Scrapbook Brian Hanrahan 15 Motor Racing Today Innes Ireland 15 The Jack Brabham Story Jack Brabham 35 Riley – the production & competition History pre 1939 A T Birmingham 45 Vanwall – the story of Tony Vanwall Denis Jenkinson 45 & his racing cars. -

Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2 Tuesday 14 May 2013 10:30

Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2 Tuesday 14 May 2013 10:30 Graham Budd Auctions Ltd Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Graham Budd Auctions Ltd (Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 335 restrictions and 144 meetings were held between Easter 1940 Two framed 1929 sets of Dirt Track Racing cigarette cards, and VE Day 1945. 'Thrills of the Dirt Track', a complete photographic set of 16 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 given with Champion and Triumph cigarettes, each card individually dated between April and June 1929, mounted, framed and glazed, 38 by 46cm., 15 by 18in., 'Famous Dirt Lot: 338 Tack Riders', an illustrated colour set of 25 given with Ogden's Post-war 1940s-50s speedway journals and programmes, Cigarettes, each card featuring the portrait and signature of a including three 1947 issues of The Broadsider, three 1947-48 successful 1928 rider, mounted, framed and glazed, 33 by Speedway Reporter, nine 1949-50 Speedway Echo, seventy 48cm., 13 by 19in., plus 'Speedway Riders', a similar late- three 1947-1955 Speedway Gazette, eight 8 b&w speedway 1930s illustrated colour set of 50 given with Player's Cigarettes, press photos; plus many F.I.M. World Rider Championship mounted, framed and glazed, 51 by 56cm., 20 by 22in.; sold programmes 1948-82, including overseas events, eight with three small enamelled metal speedway supporters club pin England v. Australia tests 1948-53, over seventy 1947-1956 badges for the New Cross, Wembley and West Ham teams and Wembley -

Old Time Show

Poste Italiane S.p.A. Spedizione in A.P. D.L. 353/2003 (convertito in L. 27/02/04 n. 46) art. 1 comma 1 - Aut. n. 0033/RA In caso di mancato recapito restituire all’ufficio accettazione CDM di Ravenna per la restituzione al mittente che si impegna a pagare la relativa tariffa. N O T I Z I A R I O D E L C L “ U G B i R r O o M d A G i N M O a L O n A o U v O T e O l l E a M ” l O è T d O o D n ’ E - P l O i n C T e A s u i l s m i t o w w e w . c r a m S A n e n o . i 1 t h N . 1 A o P R I L E w 2 0 1 8 Calendario manifestazioni 2018 VI ASPETTIAMO! NOTIZIARIO DEL CLUB ROMAGNOLO AUTO E MOTO D’EPOCA Anno1 N.1 APRILE 2018 “Giro di Manovella” è on-line sul sito www.crame.it Old Time Show . a f f i r a t a v i t a l e r a l e r a g a p a a n g e p m i . i O s B - e B h c C D e - t 1 n e a t t i m m m l o c a 1 e n . t o i r z a u ) t i 6 t 4 s e . -

Thebusinessofmotorsport ECONOMIC NEWS and ANALYSIS from the RACING WORLD

Contents: 2 November 2009 Doubts over Toyota future Renault for sale? Mercedes and McLaren: divorce German style USF1 confirms Aragon and Stubbs Issue 09.44 Senna signs for Campos New idea in Abu Dhabi Bridgestone to quit F1 at the end of 2010 Tom Wheatcroft A Silverstone deal close Graham Nearn Williams to confirm Barrichello and Hulkenberg this week Vettel in the twilight zone thebusinessofmotorsport ECONOMIC NEWS AND ANALYSIS FROM THE RACING WORLD Doubts over Toyota future Toyota is expected to announce later this week that it will be withdrawing from Formula 1 immediately. The company is believed to have taken the decision after indications in Japan that the automotive markets are not getting any better, Honda having recently announced a 56% drop in earnings in the last quarter, compared to 2008. Prior to that the company was looking at other options, such as selling the team on to someone else. This has now been axed and the company will simply close things down and settle all the necessary contractual commitments as quickly as possible. The news, if confirmed, will be another blow to the manufacturer power in F1 as it will be the third withdrawal by a major car company in 11 months, following in the footsteps of Honda and BMW. There are also doubts about the future of Renault's factory team. The news will also be a blow to the Formula One Teams' Association, although the members have learned that working together produces much better results than trying to take on the authorities alone. It also means that there are now just three manufacturers left: Ferrari, Mercedes and Renault, and engine supply from Cosworth will become essential to ensure there are sufficient engines to go around. -

PDF Download

NEW Press Information Coburg, December 10th, 2010 NEW 2 The legend returns. The NEW STRATOS will be officially presented on 29./30.11.2010, at the Paul Ricard Circuit in Le Castellet. The legendary Lancia Stratos HF was without a doubt the most spectacular and successful rally car of the 70s. With its thrilling lines and uncompro- mising design tailored to rally use, the Stratos not only single-handedly rewrote the history of rallying, it won a permanent place in the hearts of its countless fans with its dramatic performance on the world’s asphalt and gravel tracks – a performance which included three successive world championship titles. For Michael Stoschek, a collector and driver of historic racing cars, as well as a successful entrepreneur in the automotive supply industry, the development and construction of a modern version of the Stratos represents the fulfillment of a long-held dream. Back in 2003, the dream had already begun to take on a concrete form; now, at last, it has become a reality: In November 2010, forty years after the Stratos’ presentation at the Turin Motor Show, the New Stratos will be publicly presented for the first time at the Paul Ricard Circuit. The legend returns. NEW 3 A retrospective. It all began in 1970, at the Turin exhibition stand of the automobile designer, Bertone. The extreme Stratos study on display there – a stylistic masterpiece by the designer Marcello Gandini – didn’t just excite visitors, but caught the attention of Cesare Fiorio, Lancia’s team manager at the time… and refused to let go. -

Formula 1 Race Car Performance Improvement by Optimization of the Aerodynamic Relationship Between the Front and Rear Wings

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Engineering FORMULA 1 RACE CAR PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT BY OPTIMIZATION OF THE AERODYNAMIC RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE FRONT AND REAR WINGS A Thesis in Aerospace Engineering by Unmukt Rajeev Bhatnagar © 2014 Unmukt Rajeev Bhatnagar Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science December 2014 The thesis of Unmukt R. Bhatnagar was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark D. Maughmer Professor of Aerospace Engineering Thesis Adviser Sven Schmitz Assistant Professor of Aerospace Engineering George A. Lesieutre Professor of Aerospace Engineering Head of the Department of Aerospace Engineering *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract The sport of Formula 1 (F1) has been a proving ground for race fanatics and engineers for more than half a century. With every driver wanting to go faster and beat the previous best time, research and innovation in engineering of the car is really essential. Although higher speeds are the main criterion for determining the Formula 1 car’s aerodynamic setup, post the San Marino Grand Prix of 1994, the engineering research and development has also targeted for driver’s safety. The governing body of Formula 1, i.e. Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) has made significant rule changes since this time, primarily targeting car safety and speed. Aerodynamic performance of a F1 car is currently one of the vital aspects of performance gain, as marginal gains are obtained due to engine and mechanical changes to the car. Thus, it has become the key to success in this sport, resulting in teams spending millions of dollars on research and development in this sector each year. -

1990 Primer Gran Premio De México 1990 LA FICHA

1990 Primer Gran Premio de México 1990 LA FICHA GP DE MÉXICO XIV GRAN PREMIO DE MÉXICO Sexta carrera del año 24 de junio de 1990 En el “Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez”. Distrito Federal (carrera # 490 de la historia) Con 69 laps de 4,421 m., para un total de 305.049 Km Podio: 1- A. Prost/ Ferrari 2- N. Mansell/ Ferrari 3- G. Berger/ McLaren Crono del ganador: 1h 32m 35.783s a 197.664 Kph/ prom (Grid: 13º) 9 puntos Vuelta + Rápida: Alain Prost/ Ferrari (la 58ª) de 1m 17.958s a 204.156 Kph/prom Líderes: Ayrton Senna/ McLaren (de la 1 a la 60) y, Alain Prost/ Ferrari (de la 61 a la 69) Pole position: Gerhard Berger/ McLaren-Honda 1m 17.227s a 206.089 Kph/ prom Pista: seca INSCRITOS FONDO # PILOTO NAC EQUIPO MOTOR CIL NEUM P # 1 ALAIN PROST FRA Scuderia Ferrari SpA Ferrari 641 Ferrari 036 V-12 3.5 Goodyear 2 NIGEL MANSELL ING Scuderia Ferrari SpA Ferrari 641 Ferrari 036 V-12 3.5 Goodyear 3 SATORU NAKAJIMA JAP Tyrrell Racing Organisation Tyrrell 019 Ford Cosworth DFR V-8 3.5 Pirelli 4 JEAN ALESI FRA Tyrrell Racing Organisation Tyrrell 019 Ford Cosworth DFR V-8 3.5 Pirelli 5 THIERRY BOUTSEN BÉL Canon Williams Team Williams FW-13B Renault RS2 V-10 3.5 Goodyear 6 RICCARDO PATRESE ITA Canon Williams Team Williams FW-13B Renault RS2 V-10 3.5 Goodyear 7 DAVID BRABHAM AUS Motor Racing Developments Brabham BT-59 Judd EV V-8 3.5 Pirelli 8 STEFANO MODENA ITA Motor Racing Developments Brabham BT-59 Judd EV V-8 3.5 Pirelli 9 MICHELE ALBORETO ITA Footwork Arrows Racing Arrows A-11B Ford Cosworth DFR V-8 3.5 Goodyear 10 ALEX CAFFI ITA Footwork Arrows Racing -

FINAL -SIRS-Program-Book-2018-Online.Pdf

6th Schizophrenia International Research Society Conference Integrated Prevention and Treatment: Shifting the Way We Think FLORENCE, ITALY 4 – 8 APRIL 2018 6th Schizophrenia International Research Society Conference Integrated Prevention and Treatment: Shifting the Way We Think Opening Letter Dear Attendees, It is our great pleasure to welcome you to the 6th Biennial Schizophrenia International Research Society (SIRS) Conference. SIRS is a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting research and communication about schizophrenia among research scientists, clinicians, drug developers, and policy makers internationally. We sincerely appreciate your interest in the Society and in our conference. The fifth congress in 2016 was a major success for the field attracting more than 1800 attendees from 52 countries. We anticipate an even higher attendance at this congress with most of the best investigators in the world in attendance. SIRS was founded in 2005 with the goal of bringing together scientists from around the world to exchange the latest advances in biological and psychosocial research in schizophrenia. The Society is dedicated to facilitating international collaboration to discover the causes of, and better treatments for, schizophrenia and related disorders. Part of the mission of the Society is to promote educational programs in order to effectively disseminate new research findings and to expedite the publication of new research on schizophrenia. The focus of the 6th Biennial Conference is ‘Integrated Prevention and Treatment: Shifting the Way We Think’. Under the outstanding leadership of Program Committee Chairs, Paola Dazzan, Bita Moghaddam, and Eóin Killackey, we have an exciting scientific program planned for this year. The Program Committee selected thirty-five outstanding symposia sessions out of 103 submissions. -

PDF Numbers and Names

CeLoMiManca Checklist F1 Grand Prix 1 LOGO F.I.A. 15 CIRCUITO JARAMA 28 LOGO GP 40 GILLES 52 NELSON PIQUET IN 2 LOGO GP BUENOS 16 LOGO GP PAUL MONTREAL VILLENEUVE ACTION (1/2 SX) AIRES RICARD 29 CIRCUITO 41 FERRARI 312 T5 - 53 NELSON PIQUET IN 3 CIRCUITO BUENOS 17 CIRCUITO PAUL MONTREAL GILLES VILLENEUVE ACTION (1/2 DX) AIRES RICARD 30 LOGO GP WATKINS 42 LOGO CANDY 54 LOGO PARMALAT 4 LOGO GP 18 LOGO GP BRANDS GLEN TYRRELL TEAM BRABHAM INTERLAGOS HATCH 31 CIRCUITO 43 JEAN-PIERRE 55 NELSON PIQUET AI 5 CIRCUITO 19 CIRCUITO BRANDS WATKINS GLEN JARIER BOX (1/2 SX) INTERLAGOS HATCH 32 LOGO GP LAS 44 DEREK DALY IN 56 NELSON PIQUET AI 6 LOGO GP KYALAMI 20 LOGO GP VEGAS ACTION BOX (1/2 DX) 7 CIRCUITO KYALAMI HOCKENHEIM 33 LOGO SCUDERIA 45 TYRRELL 009 - 57 RICARDO ZUNINO FERRARI JEAN PIERRE JARIER 8 LOGO GP LONG 21 CIRCUITO 58 BRABHAM BT 49 - BEACH HOCKENHEIM 34 JODY SCHECKTER 46 INCIDENTE RICARDO ZUNINO MONTECARLO (1/2 SX) 9 CIRCUITO LONG 22 LOGO GP ZELTWEG 35 JODY SCHECKTER 59 LOGO McLAREN BEACH 23 CIRCUITO IN ACTION 47 INCIDENTE 60 JOHN WATSON MONTECARLO (1/2 DX) 10 LOGO GP ZOLDER ZELTWEG 36 FERRARI 312 T5 - 61 McLAREN M 29 C - JODY SCHECKTER 48 TYRRELL 009 - 11 CIRCUITO ZOLDER 24 LOGO GP JOHN WATSON ZANDVOORT 37 GILLES DEREK DALY 12 LOGO GP 62 McLAREN M 29 C - VILLENEUVE AI BOX 49 DEREK DALY MONTECARLO 25 CIRCUITO ALAIN PROST ZANDVOORT 38 JODY SCHECKTER 50 NELSON PIQUET 13 CIRCUITO 63 ALAIN PROST AI BOX (1/2 ALTO) MONTECARLO 26 LOGO GP MONZA 51 BRABHAM BT 49 - 64 LOGO ATS TEAM 39 JODY SCHECKTER NELSON PIQUET 14 LOGO GP JARAMA 27 CIRCUITO MONZA -

Formula E Finale Buemi Survives Clash to Take the Crown #%%'.'4#6' +0018#6+10

AUSTRIAN GP WHAT MERC CRASH TANAK DENIED SURPRISE 16-PAGE REPORT MEANS FOR FORMULA 1 WORLD RALLY VICTORY HAMILTON WINS… ROSBERG FUMES As Wolff threatens team orders “I don’t want contact anymore” FORMULA E FINALE BUEMI SURVIVES CLASH TO TAKE THE CROWN #%%'.'4#6' +0018#6+10 ÜÜÜ°>Û°VÉÀ>V} 5+/7.#6' '0)+0''4 /#-' 6'56 4#%' AUSTRIAN GP WHAT MERC CRASH TANAK DENIED SURPRISE 16-PAGE REPORT MEANS FOR FORMULA 1 WORLD RALLY VICTORY HAMILTON WINS… ROSBERG FUMES COVER IMAGES As Wolff threatens team orders “I don’t want contact anymore” Etherington/LAT; FORMULA E FINALE Charniaux/XPB; BUEMI SURVIVES CLASH TO TAKE THE CROWN Rajan Jangda/e-racing.net COVER STORY 4 Austrian Grand Prix report and analysis PIT+PADDOCK 20 FIA aims to boost motorsport worldwide 22 New manufacturers for Formula E 25 Feedback: your letters 27 Ian Parkes: in the paddock REPORTS AND FEATURES XPB IMAGES 28 Buemi takes Formula E title as Prost wins 34 Heartache for Tanak in Rally Poland 40 Suzuki: the sleeping giant of MotoGP Nico still struggling to RACE CENTRE 46 GP2; GP3; Blancpain Sprint Cup; NASCAR Sprint Cup; Formula get the balance right Renault Eurocup; IMSA SportsCar NICO ROSBERG JUST CAN’T QUITE GET IT RIGHT. WHEN CLUB AUTOSPORT it comes to wheel-to-wheel battles, he is either too soft or overly 65 Will Palmer to race in BRDC F3 at Spa robust. He usually comes off worst too, particularly when fi ghting 66 Crack Mercedes squad for British GT Mercedes ‘team-mate’ and title rival Lewis Hamilton. -

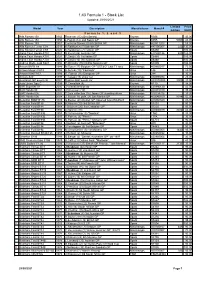

Stock List Updated 28/09/2021

1:43 Formula 1 - Stock List Updated 28/09/2021 Limited Price Model Year Description Manufacturer Manuf # Edition (AUD) F o r m u l a 1 , 2 a n d 3 Alfa Romeo 158 1950 Race car (25) (Oro Series) Brumm R036 35.00 Alfa Romeo 158 1950 L.Fagioli (12) 2nd Swiss GP Brumm S055 5000 40.00 Alfa Romeo 159 1951 Consalvo Sanesi (3) 6th British GP Minichamps 400511203 55.00 Alfa Romeo Ferrari C38 2019 K.Raikkonen (7) Bahrain GP Minichamps 447190007 222 135.00 Alfa Romeo Ferrari C39 2020 K.Raikkonen (7) Turkish GP Spark S6492 100.00 Alpha Tauri Honda AT01 2020 D.Kvyat (26) Austrian GP Minichamps 417200126 400 125.00 Alpha Tauri Honda AT01 2020 P.Gasly (10) 1st Italian GP Spark S6480 105.00 Alpha Tauri Honda AT01 2020 P.Gasly (10) 7th Austrian GP Spark S6468 100.00 Andrea Moda Judd S921 1992 P.McCathy (35) DNPQ Monaco GP Spark S3899 100.00 Arrows BMW A8 1986 M.Surer (17) Belgium GP "USF&G" Last F1 race Minichamps 400860017 75.00 Arrows Mugen FA13 1992 A.Suzuki (10) "Footwork" Onyx 146 25.00 Arrows Hart FA17 1996 R. Rosset (16) European GP Onyx 284 30.00 Arrows A20 1999 T.Takagi (15) show car Minichamps 430990084 25.00 Australian GP Event car 2001 Qantas AGP Event car Minichamps AC4010300 3000 40.00 Auto Union Tipo C 1936 R.Gemellate (6) Brumm R110 38.00 BAR Supertec 01 2000 J.Villeneuve test car Minichamps 430990120 40.00 BAR Honda 03 2001 J.Villeneuve (10) Minichamps 400010010 35.00 BAR Honda 005 2003 T.Sato collection (16) Japan GP standing driver Minichamps 518034316 35.00 BAR Honda 006 2004 J.