A War in Heaven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Place in Philology: an Attempt to Show That the Languages of Europe and Asia Have a Common Origin

CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT Of CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF IB76 1918 Cornell University Library P 201.E23 China's place in phiiologyian attempt toI iPii 3 1924 023 345 758 CHmi'S PLACE m PHILOLOGY. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023345758 PLACE IN PHILOLOGY; AN ATTEMPT' TO SHOW THAT THE LANGUAGES OP EUROPE AND ASIA HAVE A COMMON OKIGIIS". BY JOSEPH EDKINS, B.A., of the London Missionary Society, Peking; Honorary Member of the Asiatic Societies of London and Shanghai, and of the Ethnological Society of France, LONDON: TRtJBNEE & CO., 8 aito 60, PATEENOSTER ROV. 1871. All rights reserved. ft WftSffVv PlOl "aitd the whole eaeth was op one langtta&e, and of ONE SPEECH."—Genesis xi. 1. "god hath made of one blood axl nations of men foe to dwell on all the face of the eaeth, and hath detee- MINED the ITMTIS BEFOEE APPOINTED, AND THE BOUNDS OP THEIS HABITATION." ^Acts Xvil. 26. *AW* & ju€V AiQionas fiereKlaOe tij\(J6* i6j/ras, AiOioiras, rol Si^^a SeSafarat effxarot av8p&Vf Ol fiiv ivffofievov Tireplovos, oi S' avdv-rof. Horn. Od. A. 22. TO THE DIRECTORS OF THE LONDON MISSIONAEY SOCIETY, IN EECOGNITION OP THE AID THEY HAVE RENDERED TO EELIGION AND USEFUL LEAENINO, BY THE RESEARCHES OP THEIR MISSIONARIES INTO THE LANGUAOES, PHILOSOPHY, CUSTOMS, AND RELIGIOUS BELIEFS, OP VARIOUS HEATHEN NATIONS, ESPECIALLY IN AFRICA, POLYNESIA, INDIA, AND CHINA, t THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. -

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-Linguistic Status : a Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-linguistic Status: A Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany by Ted Cicholi RN (Psych.), MA. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science School of Government 22 September 2004 Disclaimer Although every effort has been taken to ensure that all Hyperlinks to the Internet Web sites cited in this dissertation are correct at the time of writing, no responsibility can be taken for any changes to these URL addresses. This may change the format as being either underlined, or without underlining. Due to the fickle nature of the Internet at times, some addresses may not be found after the initial publication of an article. For instance, some confusion may arise when an article address changes from "front page", such as in newspaper sites, to an archive listing. This dissertation has employed the Australian English version of spelling but, where other works have been cited, the original spelling has been maintained. It should be borne in mind that there are a number of peculiarities found in United States English and Australian English, particular in the spelling of a number of words. Interestingly, not all errors or irregularities are corrected by software such as Word 'Spelling and Grammar Check' programme. Finally, it was not possible to insert all the accents found in other languages and some formatting irregularities were beyond the control of the author. Declaration This dissertation does not contain any material which has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any tertiary institution. -

Comac Medical NLSP2 Thefo

Issue May/14 No.2 Copyright © 2014 Comac Medical. All rights reserved Dear Colleagues, The Newsletter Special Edition No.2 is dedicated to the 1150 years of the Moravian Mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius and 1150 years of the official declaration of Christianity as state religion in Bulgaria by Tsar Boris I and imposition of official policy of literacy due to the emergence of the fourth sacral language in Europe. We are proudly presenting: • PUBLISHED BY COMAC-MEDICAL • ~Page I~ SS. CIRYL AND METHODIUS AND THE BULGARIAN ALPHABET By rescuing the creation of Cyril and Methodius, Bulgaria has earned the admiration and respect of not only the Slav peoples but of all other peoples in the world and these attitudes will not cease till mankind keeps implying real meaning in notions like progress, culture “and humanity. Bulgaria has not only saved the great creation of Cyril and Methodius from complete obliteration but within its territories it also developed, enriched and perfected this priceless heritage (...) Bulgaria became a living hearth of vigorous cultural activity while, back then, many other people were enslaved by ignorance and obscurity (…) Тhe language “ of this first hayday of Slavonic literature and culture was not other but Old Bulgarian. This language survived all attempts by foreign invaders for eradication thanks to the firmness of the Bulgarian people, to its determination to preserve what is Bulgarian, especially the Bulgarian language which has often been endangered but has never been subjugated… -Prof. Roger Bernard, French Slavist Those who think of Bulgaria as a kind of a new state (…), those who have heard of the Balkans only as the “powder keg of Europe”, those cannot remember that “Bulgaria was once a powerful kingdom and an active player in the big politics of medieval Europe. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

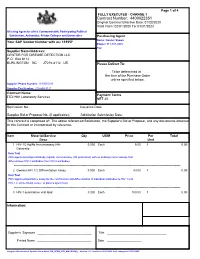

Fully Executed

Page 1 of 4 FULLY EXECUTED - CHANGE 1 Contract Number: 4400022351 Original Contract Effective Date: 01/22/2020 Valid From: 02/01/2020 To: 01/31/2023 All using Agencies of the Commonwealth, Participating Political Subdivision, Authorities, Private Colleges and Universities Purchasing Agent Name: Danner Shawn Your SAP Vendor Number with us: 135557 Phone: 717-787-8085 Fax: Supplier Name/Address: CENTER FOR DISEASE DETECTION LLC P.O. Box 8112 BURLINGTON NC 27216-8112 US Please Deliver To: To be determined at the time of the Purchase Order unless specified below. Supplier Phone Number: 2109515189 Supplier Fax Number: 210-590-3121 Contract Name: Payment Terms STD/ HIV Laboratory Services NET 30 Solicitation No.: Issuance Date: Supplier Bid or Proposal No. (if applicable): Solicitation Submission Date: This contract is comprised of: The above referenced Solicitation, the Supplier's Bid or Proposal, and any documents attached to this Contract or incorporated by reference. Item Material/Service Qty UOM Price Per Total Desc Unit 1 HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Immunoassay (4th 0.000 Each 6.00 1 0.00 Generatio Item Text FDA-approved antigen/antibody (Ag/Ab) immunoassay (4th generation) with an antibody immunoassay that differentiates HIV-1 antibodies from HIV-2 antibodies. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Geenius HIV 1/2 Differentiation Assay 0.000 Each 43.00 1 0.00 Item Text FDA-approved qualitative assay for the confirmation and differentiation -

The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016-1471

- THE CHRONICLE OF NOVGOROD 1016-1471 TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN BY ROBERT ,MICHELL AND NEVILL FORBES, Ph.D. Reader in Russian in the University of Oxford WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY C. RAYMOND BEAZLEY, D.Litt. Professor of Modern History in the University of Birmingham AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE TEXT BY A. A. SHAKHMATOV Professor in the University of St. Petersburg CAMDEN’THIRD SERIES I VOL. xxv LONDON OFFICES OF THE SOCIETY 6 63 7 SOUTH SQUARE GRAY’S INN, W.C. 1914 _. -- . .-’ ._ . .e. ._ ‘- -v‘. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE General Introduction (and Notes to Introduction) . vii-xxxvi Account of the Text . xxx%-xli Lists of Titles, Technical terms, etc. xlii-xliii The Chronicle . I-zzo Appendix . 221 tJlxon the Bibliography . 223-4 . 225-37 GENERAL INTRODUCTION I. THE REPUBLIC OF NOVGOROD (‘ LORD NOVGOROD THE GREAT," Gospodin Velikii Novgorod, as it once called itself, is the starting-point of Russian history. It is also without a rival among the Russian city-states of the Middle Ages. Kiev and Moscow are greater in political importance, especially in the earliest and latest mediaeval times-before the Second Crusade and after the fall of Constantinople-but no Russian town of any age has the same individuality and self-sufficiency, the same sturdy republican independence, activity, and success. Who can stand against God and the Great Novgorod ?-Kto protiv Boga i Velikago Novgoroda .J-was the famous proverbial expression of this self-sufficiency and success. From the beginning of the Crusading Age to the fall of the Byzantine Empire Novgorod is unique among Russian cities, not only for its population, its commerce, and its citizen army (assuring it almost complete freedom from external domination even in the Mongol Age), but also as controlling an empire, or sphere of influence, extending over the far North from Lapland to the Urals and the Ob. -

University of Tarty Faculty of Philosophy Department of History

UNIVERSITY OF TARTY FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY LINDA KALJUNDI Waiting for the Barbarians: The Imagery, Dynamics and Functions of the Other in Northern German Missionary Chronicles, 11th – Early 13th Centuries. The Gestae Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum of Adam of Bremen, Chronica Slavorum of Helmold of Bosau, Chronica Slavorum of Arnold of Lübeck, and Chronicon Livoniae of Henry of Livonia Master’s Thesis Supervisor: MA Marek Tamm, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales / University of Tartu Second supervisor: PhD Anti Selart University of Tartu TARTU 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 I HISTORICAL CONTEXTS AND INTERTEXTS 5 I.1 THE SOURCE MATERIAL 5 I.2. THE DILATATIO OF LATIN CHRISTIANITY: THE MISSION TO THE NORTH FROM THE NINTH UNTIL EARLY THIRTEENTH CENTURIES 28 I.3 NATIONAL TRAGEDIES, MISSIONARY WARS, CRUSADES, OR COLONISATION: TRADITIONAL AND MODERN PATTERNS IN HISTORIOGRAPHY 36 I.4 THE LEGATIO IN GENTES IN THE NORTH: THE MAKING OF A TRADITION 39 I.5 THE OTHER 46 II TO DISCOVER 52 I.1 ADAM OF BREMEN, GESTA HAMMABURGENSIS ECCLESIAE PONTIFICUM 52 PERSONAE 55 LOCI 67 II.2 HELMOLD OF BOSAU, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 73 PERSONAE 74 LOCI 81 II.3 ARNOLD OF LÜBECK, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 86 PERSONAE 87 LOCI 89 II.4 HENRY OF LIVONIA, CHRONICON LIVONIAE 93 PERSONAE 93 LOCI 102 III TO CONQUER 105 III.1 ADAM OF BREMEN, GESTA HAMMABURGENSIS ECCLESIAE PONTIFICUM 107 PERSONAE 108 LOCI 128 III.2 HELMOLD OF BOSAU, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 134 PERSONAE 135 LOCI 151 III.3 ARNOLD OF LÜBECK, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 160 PERSONAE 160 LOCI 169 III.4 HENRY OF LIVONIA, CHRONICON LIVONIAE 174 PERSONAE 175 LOCI 197 SOME CONCLUDING REMARKS 207 BIBLIOGRAPHY 210 RESÜMEE 226 APPENDIX 2 Introduction The following thesis discusses the image of the Slavic, Nordic, and Baltic peoples and lands as the Other in the historical writing of the Northern mission. -

Nominalia of the Bulgarian Rulers an Essay by Ilia Curto Pelle

Nominalia of the Bulgarian rulers An essay by Ilia Curto Pelle Bulgaria is a country with a rich history, spanning over a millennium and a half. However, most Bulgarians are unaware of their origins. To be honest, the quantity of information involved can be overwhelming, but once someone becomes invested in it, he or she can witness a tale of the rise and fall, steppe khans and Christian emperors, saints and murderers of the three Bulgarian Empires. As delving deep in the history of Bulgaria would take volumes upon volumes of work, in this essay I have tried simply to create a list of all Bulgarian rulers we know about by using different sources. So, let’s get to it. Despite there being many theories for the origin of the Bulgars, the only one that can show a historical document supporting it is the Hunnic one. This document is the Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans, dating back to the 8th or 9th century, which mentions Avitohol/Attila the Hun as the first Bulgarian khan. However, it is not clear when the Bulgars first joined the Hunnic Empire. It is for this reason that all the Hunnic rulers we know about will also be included in this list as khans of the Bulgars. The rulers of the Bulgars and Bulgaria carry the titles of khan, knyaz, emir, elteber, president, and tsar. This list recognizes as rulers those people, who were either crowned as any of the above, were declared as such by the people, despite not having an official coronation, or had any possession of historical Bulgarian lands (in modern day Bulgaria, southern Romania, Serbia, Albania, Macedonia, and northern Greece), while being of royal descent or a part of the royal family. -

|||GET||| Internal Colonization in Medieval Europe 1St Edition

INTERNAL COLONIZATION IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Felipe FernГѓВЎndez-Armesto | 9781351927024 | | | | | History of Germans in Poland German immigrants were also important in the rise of the cities and the establishment of the Polish burgher city-dwelling merchant class; they brought with them West European laws Magdeburg rights and customs which the Poles adopted. The Polish princes granted the Germans in the cities complete autonomy according to the " Teutonic right" later, " Magdeburg right "modeled on the laws of the cities of ancient Rome. Weimar Republic. An attempt is made As virtually all of the Western Baltic pagans became converted or exterminated the Prussian conquests were completed bythe Knights confronted Poland and Lithuaniathen the last pagan state in Europe. Even though the majority of the settlers were Germans Franks and Bavarians in the South, and Saxons and Flemings in the NorthWends and other tribes also participated in the settlement. Introducing Discourse Analysis: From Grammar to Society is a concise and accessible introduction by bestselling Both began to invite German settlers in order to develop their realm economically and to extend their rule. In the Middle Ages and today, it is the Romani—who consider themselves an ethnoracial group, despite Internal Colonization in Medieval Europe 1st edition internal heterogeneity among their peoples—who best personify the paradox of race and racial identification. Medieval Europe between 5th and 8th centuries, also referred to as the Dark Ages was marked by rise of numerous short-lived barbarian kingdoms and a period of general instability that delivered the final blow to long distance trade and manufacture for export as it was no longer safe to travel to any distance, especially after the Muslim conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries. -

Films Refusés, Du Moins En Première Instance, Par La Censure 1917-1926 N.B

Films refusés, du moins en première instance, par la censure 1917-1926 N.B. : Ce tableau dresse, d’après les archives de la Régie du cinéma, la liste de tous les refus prononcés par le Bureau de la censure à l’égard d’une version de film soumise pour approbation. Comme de nombreux films ont été soumis plus d’une fois, dans des versions différentes, chaque refus successif fait l’objet d’une nouvelle ligne. La date est celle de la décision. Les « Remarques » sont reproduites telles qu’elles se trouvent dans les documents originaux, accompagnées parfois de commentaires entre [ ]. 1632 02 janv 1917 The wager Metro Immoral and criminal; commissioner of police in league with crooks to commit a frame-up robbery to win a wager. 1633 04 janv 1917 Blood money Bison Criminal and a very low type. 1634 04 janv 1917 The moral right Imperial Murder. 1635 05 janv 1917 The piper price Blue Bird Infidelity and not in good taste. 1636 08 janv 1917 Intolerance Griffith [Version modifiée]. Scafold scenes; naked woman; man in death cell; massacre; fights and murder; peeping thow kay hole and girl fixing her stocking; scenes in temple of love; raiding bawdy house; kissing and hugging; naked statue; girls half clad. 1637 09 janv 1917 Redeeming love Morosco Too much caricature on a clergyman; cabaret gambling and filthy scenes. 1638 12 janv 1917 Kick in Pathé Criminal and low. 1639 12 janv 1917 Her New-York Pathé With a tendency to immorality. 1640 12 janv 1917 Double room mystery Red Murder; robbery and of low type. -

Collegium Medievale 16

• t Ii j COLLEGIUM MEDIEVALE Tverrfaglig tidsskrift for middelalderforskning Interdisciplinary Journal of Medieval Research Volume 16 2003 Published by COLLEGIUM MEDIEVALE Society for Medieval Studies Oslo 2003 Study into Socio-political History of the Obodrites Roman Zaroff Artikkelen be handler de polabiske slaviske starnrnene som bodde i omradet mellom elvene Elbe-Saale og Oder-Neisse, i perioden fra slutten av 700-tallet til 1100- tallet. Artikkelforfatteren gar imot det hevdvunne synet om at disse slaverne forble organisert i sma, lokale stammer. Tvert imot men er forfatteren a kunne belegge at disse polabiske slaveme pga. sterkt ytre press i perioden organiserte seg i en storre sammenslutning over stammeniva, sentrert rundt obotritt-stammen. Denne sammenslutningen var en politisk enhet pa linje med samtidige tyske hertugdommer og markomrader og de skandinaviske landene. Introduction The Western Slavs once occupied the territory more or less corresponding to the former state of East Germany that is the area roughly between the Oder-Neisse and Elbe-Saale rivers. They are usually called the Polabian Slavs or Wends. They were the westernmost group of the Western Slavs (which includes the Czechs, Poles and Slovaks) who settled the region between the sixth and seventh centu ries. 1 The Polabian Slavs are usually divided into three branches: the Sorbs, who occupied roughly the southern part ofthe former East Germany; the Veleti in the northeast of the region; and the Obodrites in the northwest.2 Most of the Polabian Slavs were germanised in the course of time, and only a small Sorbian minority in southeastern Germany retains its linguistic and cultural identity until the present day.' 1 Dvomik 1974:14; and Gimbutas 1971:124-128; and towmianski 1967:98, 221; and Strzelczyk 1976:139-154. -

Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer OFF0021

Run Date: 4/11/2020 8:41:00AM Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing Club Officer for 2019-2020(Only President, Secretary,Treasurer, Membership Chair) Undistricted Club Club Name Title (Missing) 27947 MALTA HOST (MALTA) Membership Chair 27947 MALTA HOST (MALTA) President 27947 MALTA HOST (MALTA) Treasurer 27949 PAPEETE (TAHITI) Membership Chair 27952 MONACO (PRIN OF MONACO) Membership Chair 38921 MANILA CENTRUM (PHILIPPINES) Membership Chair 38921 MANILA CENTRUM (PHILIPPINES) President 38921 MANILA CENTRUM (PHILIPPINES) Secretary 38921 MANILA CENTRUM (PHILIPPINES) Treasurer 44697 ANDORRA DE VELLA (PRINCIPAT D'ANDORRA) Membership Chair 47478 DUMBEA (NEW CALEDONIA) Secretary 53760 LIEPAJA (REP OF LATVIA) Membership Chair 54276 BOURAIL LES ORCHIDEES (NEW CALEDONIA) Membership Chair 54276 BOURAIL LES ORCHIDEES (NEW CALEDONIA) Secretary 55216 MDINA (MALTA) Membership Chair 57412 ALUKSNE (REP OF LATVIA) Membership Chair 60727 PHNOM PENH OBAYKHOM (CAMBODIA,KINGDOM OF) Membership Chair 62548 VALMIERA (REP OF LATVIA) Membership Chair 63267 SVETLOGORSK (BELARUS REP.) Membership Chair 63886 ULAANBAATAR KHERLEN (MONGOLIA) Membership Chair 68947 SARAJEVO CENTAR (BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA) President 68947 SARAJEVO CENTAR (BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA) Secretary 78634 TBILISI GEORGIAN (REP OF GEORGIA) Membership Chair 78634 TBILISI GEORGIAN (REP OF GEORGIA) President 78634 TBILISI GEORGIAN (REP OF GEORGIA) Secretary 78634 TBILISI GEORGIAN (REP OF GEORGIA) Treasurer 99266 SOFIA VITOSHA (BULGARIA) Membership Chair OFF0021 © Copyright 2020, Lions Clubs International,