Lapkoff & Gobalet Demographic Research, Inc. Demographic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAN FRANCISCO 2Nd Quarter 2014 Office Market Report

SAN FRANCISCO 2nd Quarter 2014 Office Market Report Historical Asking Rental Rates (Direct, FSG) SF MARKET OVERVIEW $60.00 $57.00 $55.00 $53.50 $52.50 $53.00 $52.00 $50.50 $52.00 Prepared by Kathryn Driver, Market Researcher $49.00 $49.00 $50.00 $50.00 $47.50 $48.50 $48.50 $47.00 $46.00 $44.50 $43.00 Approaching the second half of 2014, the job market in San Francisco is $40.00 continuing to grow. With over 465,000 city residents employed, the San $30.00 Francisco unemployment rate dropped to 4.4%, the lowest the county has witnessed since 2008 and the third-lowest in California. The two counties with $20.00 lower unemployment rates are neighboring San Mateo and Marin counties, $10.00 a mark of the success of the region. The technology sector has been and continues to be a large contributor to this success, accounting for 30% of job $0.00 growth since 2010 and accounting for over 1.5 million sf of leased office space Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 2012 2012 2012 2013 2013 2013 2013 2014 2014 this quarter. Class A Class B Pre-leasing large blocks of space remains a prime option for large tech Historical Vacancy Rates companies looking to grow within the city. Three of the top 5 deals involved 16.0% pre-leasing, including Salesforce who took over half of the Transbay Tower 14.0% (delivering Q1 2017) with a 713,727 sf lease. Other pre-leases included two 12.0% full buildings: LinkedIn signed a deal for all 450,000 sf at 222 2nd Street as well 10.0% as Splunk, who grabbed all 182,000 sf at 270 Brannan Street. -

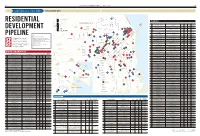

Residential Development Pipeline

36 SAN FRANCISCO BUSINESS TIMES JUNE 26, 2015 37 SAN FRANCISCO STRUCTURES SPECIAL REPORT Columbus Ave. The Embarcadero 52 SPONSORED BY Broadway Pacific Ave. Kearny St. PLANNED Stockton St. RESIDENTIAL Jackson St. Powell St. Montgomery St. SAN FRANCISCO Polk St. 80 Project name, address Developer Done Units Sale/ Market/ Sacramento St. rental affordable NP 1654 Sunnydale Ave. Mercy Housing California, Related Cos. 2018+ 1,700 both both 34 40 78 106 DEVELOPMENT 14 Pine St. 77 Potrero Terrace, 1095 Connecticut St. Bridge Housing Corp. 2018 1,400- both both California St. Bush St. 60 7 85 71 58 Sutter St. Spear St. 1,700 79 8 1 Main St. Mission Rock, Seawall Lot 227 and SWL 337 Associates LLC (S.F. Giants) 2017+ 1,500 TBD both Gough St. 112 35 80 5 Beale St. 72 Laguna St. 113 Webster St. Pier 48 38 Fremont St. Steiner St. Geary Blvd. 90 33 Pier 70 residential Forest City 2029 1,000- both both Divisadero St. 55 48 73 KEY 95 118 107 10 2,000 PIPELINE 2nd St. NP: Not placed; outside map area 96 Market St. 103 Van Ness Ave. 64 Ellis St. 62 61 74 700 Innes St. Build Inc. 2020 980 rent market Market: A majority of units are market rate, 29 94 1st St. Residential projects in 75 10 S. Van Ness Ave. Crescent Heights 2018+ 767 TBD market though almost all projects include some affordable Geary Blvd. Mission St. 97 San Francisco of 60 units units to comply with city regulations Turk St. 102 76 5M at Fifth and Mission Streets Forest City / Hearst Corp. -

DATE: July 11, 2013 TO: Historic Preservation Commissioners FROM: Daniel A

DATE: July 11, 2013 TO: Historic Preservation Commissioners FROM: Daniel A. Sider, Planning Department Staff RE: Market Analysis of the Sale of Publicly Owned TDR In May 2012, Planning Department (“Department”) Staff provided the Historic Preservation Commission (“HPC”) an informational presentation on the City’s Transferable Development Rights (“TDR”) program. In February 2013, the Department retained Seifel Consulting, Inc. and C.H. Elliott & Associates (jointly, “Consultants”) to perform a market analysis informing a possible sale of TDR from City-owned properties. The resulting work product (“Report”) was delivered to the Department in late June. This memo and the attached Report are intended to provide the HPC with relevant follow-up information from the May 2012 hearing. The City’s TDR Program Since the mid-1980’s, the Planning Department has administered a TDR program (“Program”) through which certain historic properties can sell their unused development rights to certain non- historic properties. The program emerged from the 1985 Downtown Plan in response to unprecedented office growth, housing impacts, transportation impacts and the loss of historic buildings. The key goal of the Program is to maintain Downtown’s development potential while protecting historic resources. The metric that underpins the Program is Floor Area Ratio ("FAR"), which is the ratio of a building’s gross square footage to that of the parcel on which it sits. Under the Program, a Landmark, Significant, or Contributory building can sell un-built FAR capacity to a non-historic property which can then use it to supplement its base FAR allowance. TDRs can only be used to increase FAR within applicable height and bulk controls. -

Transbay Joint Powers Authority

NEW ISSUE – Book-Entry Only RATINGS: See “RATINGS” In the opinion of Bond Counsel, under existing law and assuming compliance with the tax covenants described herein, and the accuracy of certain representations and certifications made by the Authority, interest on the 2020 Tax-Exempt Bonds is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes under Section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”). Bond Counsel is also of the opinion that interest on the 2020 Tax-Exempt Bonds is not treated as a preference item in calculating the alternative minimum tax imposed under the Code. Interest on the Senior 2020A-T Bonds is not excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes. Bond Counsel is further of the opinion that interest on the 2020 Bonds is exempt from personal income taxes of the State of California (the “State”) under present State law. See “2020 TAX-EXEMPT BONDS TAX MATTERS” and “SENIOR 2020A-T BONDS TAX MATTERS” in this Official Statement regarding certain other tax considerations. TRANSBAY JOINT POWERS AUTHORITY $189,480,000 $28,355,000 Senior Tax Allocation Bonds Senior Tax Allocation Bonds Series 2020A (Tax-Exempt) (Green Bonds) Series 2020A-T (Federally Taxable) (Green Bonds) $53,370,000 Subordinate Tax Allocation Bonds Series 2020B (Tax-Exempt) (Green Bonds) Dated: Date of Delivery Due: October 1, as shown on inside cover Bonds. The Transbay Joint Powers Authority (the “Authority”) is issuing the above-captioned bonds (the “Senior 2020A Bonds,” the “Senior 2020A-T Bonds,” and the “Subordinate 2020B Bonds” and, collectively, the “2020 Bonds”). -

Issues Are Being Reported Throughout All of San Francisco and What the City Is Doing to Resolve Them

NO. 160 PUBLISHED BY THE CENTRAL CITY A telling tale SAN FRANCISCO STUDY CENTER October of challenges 2 015 for housing 4,400 in The City UNITS IN 1400 Mission began as 25 YEARS low-income, but city made san francisco it plum for a smart builder Affordable housing built UNK S ENDERLOIN OOTS BY M ARJORIE BEGGS P ‘ T R since 1989 T WAS A SWEET BIT of chronologi- cal serendipity: In August, the city an- PAGE 3 I nounced the moderate-income lottery winners who were eligible to buy 167 condos at the new, glass-clad 1400 Mission complex at the corner of 10th Street. Two miles east, at Folsom and Main streets, the first owners began moving into Lumina, 656 super-luxe condos. The connection between the two is direct, the timing’s not coincidental, the backstory convoluted — and telling. Tishman Speyer built 1400 Mission for $65 million and Lumina for $620 million. One is inclusionary affordable housing, the other, by dint of price, exclusionary. With the exception of 23 rental apartments at 1400 Mission, all 823 condos are for sale. How much Tishman will profit from Lumina will probably be known only to Tishman Speyer. At 1400 Mission, the city 2 WHO has posted estimated sales totals for the WERE The city credited Tishman 167 condos at just nearly $50 million for under $50 million. So MOURNED meeting its inclusionary it may be fair to ask if Deosia Henderson, requirement. the big developer has used an affordable Stevie L. Newsom housing project to en- able its lucrative investment in the Lumina. -

August 2015 San Francisco Residential

SAN FRANCISCO RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT AUGUST 2015 REPORT CONTENTS click page numbers to be taken directly to page STATE OF DEVELOPMENT MARKET PERFORMANCE CURRENTLY SELLING Median $/SqFt Currently Year-Over-Year Month-Over-Month Mission Rock is San Francisco’s newest Luxe planned community to hit center stage. In New Condominium $1,196/SqFt 18% 1% November, San Francisco voters will de- Resale Condominium $1,021/SqFt 13% 0% 1650 Broadway at Van Ness | Pacific Heights cide the fate of an Initiative which calls for Status: 34 units available/0 in-contract/0 closed New Apartment $5.10/SqFt 7% n/a increasing allowable building heights up to Pre-sale: August 2015 Closings anticipated: Q1 2016 240 feet at the Development Site, locat- Project info: 34 units, 7-stories, 34 parking spaces ed just South of AT&T Park. In 2014, Voters NEW CONDOMINIUM PRICING & VOLUME passed Proposition B, requiring voter ap- Developer: Belrich Partners proval of height increases along Waterfront Architect: Forum Design Median Price & Closing Volume land owned by the Port. The November Interior Design: Edmonds + Lee Initiative proposes heights between 90 and $1,200,000 180 Features & Finishes: Marble tile and zinc facade, Floor- 160 240 feet, stepping down heights closer to $1,000,000 to-ceiling windows, Bay and Golden Gate views, Studio the Waterfront. Part of the Site currently 140 Most Recent Quarter Becker Cabinetry, Mobile kitchen islands, Caesarstone serves as the Giants’ parking lot, while the $800,000 120 countertops, Subzero refrigerators, Thermador ap- 100 Median: $1,000,000 $600,000 pliances, Uline wine coolers, Duravit and Hansgrohe rest consists of historic Piers in need of 80 fixtures, Victoria + Albert limestone soaking tubs, restoration. -

Before the Public Utilities Commission of the State of California

BEFORE THE PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA Order Instituting Rulemaking to Consider Alternative-Fueled Vehicle Programs, Tariffs, and Rulemaking 13-11-007 Policies. (Filed November 14, 2013) CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify that SAN DIEGO GAS & ELECTRIC COMPANY (U902E) NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY OF ELECTRIC VEHICLE-GRID INTEGRATION PILOT PROGRAM (“POWER YOUR DRIVE”) SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT has been electronically mailed to each party of record on the service list in R.13-11-007. SDG&E is unable to serve the report to A.14- 04-014 because that service list has been closed. Any party on the service list who has not provided an electronic mail address was served by placing a copy in a properly addressed and sealed envelope and depositing such envelope in the United States Mail with first-class postage prepaid. A copy was also sent via Federal Express to the Assigned Administrative Law Judge in this proceeding. Executed this 6th day of September 2016 at San Diego, California /s/ Tamara Grabowski Tamara Grabowski CPUC - Service Lists - R1311007 Page 1 of 15 CPUC Home CALIFORNIA PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION Service Lists PROCEEDING: R1311007 - CPUC - OIR TO CONSID FILER: CPUC LIST NAME: LIST LAST CHANGED: AUGUST 19, 2016 Download the Comma-delimited File About Comma-delimited Files Back to Service Lists Index Parties CAMERON SEAN GRAY JEREMY WAEN ENERGY AND TRANSPORTATION MANAGER SR. REGULATORY ANALYST COMMUNITY ENVIRONMENTAL COUNCIL MARIN CLEAN ENERGY EMAIL ONLY EMAIL ONLY EMAIL ONLY, CA 00000 EMAIL ONLY, CA 00000 FOR: COMMUNITY ENVIRONMENTAL COUNCIL FOR: MARIN CLEAN ENERGY JOHN BOESEL JOHN W. -

City and County of San Francisco

PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED JANUARY 30, 2019 NEW ISSUE - BOOK-ENTRY ONLY RATING: Fitch: “AA+” See “RATING” herein. In the opinion of Jones Hall, A Professional Law Corporation, San Francisco, California, Bond Counsel, subject, however to certain qualifications described in this Official Statement, under existing law, the interest on the Bonds is exempt from California personal income taxes. Interest on the Bonds is not intended to be exempt from federal income taxation. Bond Counsel expresses no opinion regarding other federal or State tax consequences relating to the ownership or disposition of, or the accrual or receipt of interest on, the Bonds. See “TAX MATTERS” herein. CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO COMMUNITY FACILITIES DISTRICT NO. 2014-1 (TRANSBAY TRANSIT CENTER) $31,940,000* $152,205,000* Special Tax Bonds, Series 2019A Special Tax Bonds, Series 2019B (Federally Taxable) (Federally Taxable – Green Bonds) Dated: Date of Delivery Due: September 1, as shown on inside cover This cover page contains certain information for general reference only. It is not intended to be a summary of the security or terms of this issue. Investors must read the entire Official Statement to obtain information essential to making an informed investment decision. The City and County of San Francisco, California (the “City”) on behalf of the City and County of San Francisco Community Facilities District No. 2014-1 (Transbay Transit Center) (the “District”) will be issuing Special Tax Bonds, Series 2019A (Federally Taxable) (the “2019A Bonds”) and Special Tax Bonds, Series 2019B (Federally Taxable – Green Bonds) (the “2019B Bonds” and, together with the 2019A Bonds, the “2019 Bonds”). -

50 Years of Spur 100 Years of Building a Better City

Issue 482 Agents of Change p5 Summer programming p26 Ironies of history p32 Planning in pieces p35 City of plans p45 Your turn! The San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association is 6|7.09 a member-supported nonprofit organization. Our mission is to promote good planning and good government through research, education and advocacy. Write to us at [email protected] SPUR Urbanist AGENTS OF CHANGE: AGENTS Published monthly by San Francisco SPUR Staff Events Manager Volunteer and Planning & Urban Kelly Hardesty x120 Intern Team Leader Research Association Still time to get SPUR main number [email protected] Jordan Salinger x136 415.781.8726 [email protected] on the boat! Deputy Director Membership Manager Sarah Karlinsky x129 Development Vickie Bell x121 [email protected] Associate [email protected] Rachel Seltzer x116 Public Engagement [email protected] 11th Annual Bay Accountant Director Terri Chang x128 Julie Kim x112 Transportation THE CITY BUILDERS Discovery Cruise [email protected] [email protected] Policy Director Dave Snyder x135 Citizen Planning Development Director [email protected] C M onday June 8, 2009 Institute Director Amie Latterman x115 IVI THE PROGRESSIVES & CLASSICISTS Jim Chappell x125 [email protected] Capital Campaign C [email protected] Manager ID Event Assistant Sarah Sykes x123 Join us for dinner, dancing Publications Assistant Nikki Lazarus x119 [email protected] EA Mary Davis x126 [email protected] and to see the latest in [email protected] Sustainable Develop- LI Administrative Director ment Policy Director S 50 Bay Bridge construction! Urban Center Director Lawrence Li x134 Laura Tam x137 M Diane Filippi x110 [email protected] [email protected] THE REGIONALISTS AN YEARS [email protected] Executive Director Regional Planning Go to spur.org/baycruise for D Executive Assistant/ Gabriel Metcalf x113 Director OF SPUR tickets and information. -

140 New Montgomery Street Jade Signature

Search Tags: High Rise Project Count: 30 140 New Montgomery Street San Francisco, CA Project Contacts: Carolyn Searls Completed in the mid-1920s, 140 New Montgomery Street is one of the early skyscrapers built in San Francisco. The Art Deco high-rise, originally known as the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph... Services: Building Enclosure Rehabilitation Markets: Office Keywords: Adaptive Reuse, Award Winning, Glass and Glazing, High Rise, Historic, Masonry, Masonry-Terra Cotta, National Register of Historic Places, Preservation Technology , Roof Replacement, Roofing, Windows Jade Signature Miami, FL Project Contacts: Jeffry Ceruti, Sean Homem With an oceanfront site and three floors of amenities, the Jade Signature brings a resort experience to residents’ everyday life. The fifty-five-story condominium building features an exposed cast... Services: Building Enclosure Design, Structural Design Keywords: Balcony, Below-Ground Waterproofing, Concrete, Drainage, High Rise, Residential, Waterproofing The Avery, Transbay Block 8, 400-450 Folsom Street San Francisco, CA Project Contacts: Craig Allender, Xiu Li The mixed-use development at 400 Folsom Street includes a fifty-five-story tower (The Avery) and two low-rise buildings designed by the executive architecture team of Office for Metropolitan... Services: Building Enclosure Design Keywords: Below-Ground Waterproofing, Curtain Wall, High Rise, Masonry-Brick, Plaza, Residential, Retail, Roofing, Waterproofing, Windows The Eddy, New Street Boston, MA Project Contacts: Jeffry Ceruti, Christopher Grey The Eddy, a new residential development, sits along the waterfront in East Boston. The property includes 258 rental units in a seventeen-story tower and four-story building. In addition to views... Services: Building Enclosure Design Keywords: Curtain Wall, High Rise, Preengineered/Prefabricated/Modular, Residential, Roofing, Roofing, Low-Sloped, Windows 200 North LaSalle Chicago, IL Project Contacts: Peter Babaian The Class A office building is located at 200 North LaSalle Drive in the heart of Chicago’s Loop. -

October 2015 San Francisco Residential Development

SAN FRANCISCO RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT OCTOBER 2015 NAVIGATION Click page numbers to be taken directly to page NEWS & MARKET CURRENTLY NEWS AND HIGHLIGHTS MARKETHIGHLIGHTS PERFORMANCE PERFORMANCECURRENTLY SELLING SELLING Median $/SqFt Currently Year-Over-Year Month-Over-Month CURRENTLY SELLING... Luxe New Condominium $1,218/SqFt + 15% + 2% 1650 Broadway at Van Ness | Pacific Heights Nearly half of Shipyard’s second phase is under contract. PriceResale per square Condominium foot is $1,042/SqFt + 11% + 2% averaging approximately $760. The first phase averaged approximately $660 per Status: 34 units available/0 in-contract/0 closed square foot. New Apartment $5.10/SqFt + 7% N/A Pre-sale: August 2015 Closings anticipated: Q1 2016 Less than 100 units remain available at The Rockwell. Current absorption surpasses Project info: 34 units, 7-stories, 34 parking spaces 30 units a month. p. p. Belrichp. Partners NEW CONDOMINIUM3 PRICING & VOLUME 4 Developer: 5 Sales are expected to commence this month at the second phase of Onyx , consisting Architect: Forum Design of 21 condominiums. Median Price & Closing Volume Interior Design: Edmonds + Lee Features & Finishes: Marble tile and zinc facade, Floor- Closings have commenced at Lumina’s Plaza A. Price per square$1,200,000 foot is averaging 180 approximately $1,500. to-ceiling windows, Bay and Golden Gate views, Studio 160 $1,000,000 Becker Cabinetry, Mobile kitchen islands, Caesarstone 140 Most Recent Quarter countertops, Subzero refrigerators, Thermador ap- $800,000 120 pliances, Uline wine coolers, Duravit and Hansgrohe 100 Median: $1,000,000 fixtures, Victoria + Albert limestone soaking tubs, PROPOSED... $600,000 80 Frameless glass showers; Penthouses only: Gas fire- 131 Group Housing untis have been proposed for 1798 Bryant Street$400,000 at 17th. -

Chinese Hospital Rises in Heart of Chinatown

114th Year OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE BUILDING AND CONSTRUCTION TRADES COUNCIL OF SAN FRANCISCO Volume 114, No. 1 January 2014 www.SFBuildingTradesCouncil.org Chinese Hospital Rises in Heart of Chinatown ♦ All-Union Project Starts Steel Work By Paul Burton is expected to be completed by Image courtesy of Chinese Hospital Contributing Writer the Chinese New Year of 2015. The new facility will be new hospital adjacent to the hospital’s build- in the heart of ing that opened in 1979, which Chinatown is is becoming overcrowded. being built with The construction project itself an all-union faces the challenge of being in Acrew. General contractor DPR a crowded commercial neigh- Construction completed a borhood, with heavy vehicle major concrete pour at the end and pedestrian traffic and little of December, and Herrick Steel room for heavy equipment is set to begin erecting steel this and trucks. The San Francisco month for the Chinese Hospi- Business Times noted that, tal. Demolition of the original “The neighborhood that sur- hospital building at 835 Jack- rounds the project site is always son Street built in 1924 began bustling with activity… Fish in late 2012. and produce markets, with deliveries thrice daily, populate Oldest Independent the area. And the still-active Hospital other half of Chinese Hospital, Chinese Hospital is San (continued on page 21) The new $169 million Chinese Hospital replacement project will be adjacent to the hospital’s building that Francisco’s oldest independent opened in 1979 and is expected to be completed by the Chinese New Year of 2015. community hospital and is a unique healthcare provider with a long and rich history Demo Begins on Old Bay Bridge of providing access to health care services for the Chinese ♦ Historic Photos and Computer Imaging Will be Used to Overcome Safety Challenges community.