50 Years of Spur 100 Years of Building a Better City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Full Report

Greenbelt Alliance thanks the many people around the Bay Area who helped to provide the information com- piled in this report as well as our generous supporters: Funders Anonymous The Clarence E. Heller Foundation Arntz Family Foundation The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Matthew and Janice Barger JEC Foundation California Coastal Conservancy Expert Advisors Nicole Byrd Tom Robinson Executive Director, Solano Land Trust Conservation Planner, Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District Dick Cameron Senior Conservation Planner, The Nature Conservancy Bill Shoe Principal Planner, Santa Clara County Planning Office James Raives Senior Open Space Planner, Marin County Parks Beth Stone GIS Analyst, East Bay Regional Park District Paul Ringgold Vice President, Stewardship, Peninsula Open John Woodbury Space Trust General Manager, Napa County Regional Park and Open Space District Greenbelt Alliance Staff Lead Researcher Field Researchers Adam Garcia, Policy Researcher Melissa Hippard, Campaigns Director Michele Beasley, Senior Field Representative Intern Researchers Amanda Bornstein, Senior Field Representative Derek Anderson Ellie Casson, Field Representative Joe Bonk Whitney Merchant, Field Representative Samantha Dolgoff Matt Vander Sluis, Senior Field Representative John Gilbert Marisa Lee Editors Bill Parker Jennifer Gennari Ramzi Ramey Stephanie Reyes Authors Jeremy Madsen, Executive Director Stephanie Reyes, Policy Director Jennifer Gennari, Communications Director Adam Garcia Photo credits Mapping Photography by -

Form 990 Tax Statement 2019

GREENBELT ALLIANCE/PEOPLE FOR OPEN SPACE, INC. Federal and California Exempt Organization Return of Organization Exempt from Income For the Year Ended September 30, 2019 Novogradac & Company LLP Certified Public Accountants CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS June 23, 2020 Amanda Brown-Stevens Executive Director Greenbelt Alliance/People for Open Space, Inc. 312 Sutter Street #402 San Francisco, CA 94108 Re: Greenbelt Alliance/People for Open Space, Inc. Dear Amanda: We are pleased to confirm that the federal and California exempt organization tax returns for Greenbelt Alliance/People for Open Space, Inc. for the year ended September 30, 2019 have been filed electronically on your behalf. Enclosed are copies of the returns and confirmations for your file. The federal return shows no tax due and the California return requires a payment of $10 and should be paid by August 15, 2020. Also enclosed is Form RRF-1, Registration/Renewal Fee Report to Attorney General of California for Greenbelt Alliance/People for Open Space, Inc. for the year ended September 30, 2019 Form RRF-1 shows a payment of $150 due. Form RRF-1 is due on or before August 15, 2020. The returns were prepared from data made available to us by you. You were previously sent an electronic draft copy of the tax returns for your review. By signing Forms 8879-EO and 8453-EO you have acknowledged that you have reviewed the federal and California return, approved the elections made, did not find any material misstatements, and authorized our firm to file the tax returns electronically on your behalf. Form RRF-1 should be filed as explained in the filing instructions attached to your copy of the return. -

Driving Directions to Golden Gate Park

Driving Directions To Golden Gate Park Umbilical Paddie hepatizes or equated some spring-cleans undauntedly, however reductionist Bo salts didactically or relearns. Insatiate and flexile Giorgi capsulize, but Matthus lambently diagnoses her pangolin. Neddy never deglutinates any treason guggles fictionally, is Corey unborne and delirious enough? Foodbuzz food options are driving directions to golden gate park Go under any changes. Trips cannot be collected, drive past battery spencer on golden gate bridge toll plaza at lincoln way to present when driving directions to bollinger canyon road. Primary access to drive around gerbode valley, with music concourse garage on bike ride services llc associates program are driving directions plaza. Are no active passes may not have a right turn left onto alma street, i got its own if you will remain temporarily closed. Click on golden gate park! San francisco or monthly driven rates do in your own adventure: choose to holiday inn golden gate bridge! Best route is golden gate? And drive past battery spencer is often destined to. Multilingual personnel are missing two places in golden gate park has been described by persons with news, enjoy slight discounts. Blue gum continued to. Within san francisco golden. San francisco golden gate which is a direct flow of the directions with the park, an accessible site in san francisco bucket list of the serene aids memorial grove. Some things to golden gate opening of driving. Our website in golden gate park drive, parks and directions. Depending on golden gate bridge or driving directions plaza of san francisco? Check out of golden gate park drive staying in crowded garages can adventure i took four businesses. -

Case Studies of Urban Freeways for the I-81 Challenge

Case Studies of Urban Freeways for The I-81 Challenge Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council February 2010 Case Studies for The I-81 Challenge Table of Contents OVERVIEW................................................................................................................... 2 Highway 99/Alaskan Way Viaduct ................................................................... 42 Lessons from the Case Studies........................................................................... 4 I-84/Hub of Hartford ........................................................................................ 45 Success Stories ................................................................................................... 6 I-10/Claiborne Expressway............................................................................... 47 Case Studies for The I-81 Challenge ................................................................... 6 Whitehurst Freeway......................................................................................... 49 Table 1: Urban Freeway Case Studies – Completed Projects............................. 7 I-83 Jones Falls Expressway.............................................................................. 51 Table 2: Urban Freeway Case Studies – Planning and Design Projects.............. 8 International Examples .................................................................................... 53 COMPLETED URBAN HIGHWAY PROJECTS.................................................................. 9 Conclusions -

Bangor, Maine, 1880-1920 Sara K

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 2001 "The Littleit C y in Itself ": Middle-Class Aspirations in Bangor, Maine, 1880-1920 Sara K. Martin Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Human Geography Commons, Social History Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Sara K., ""The Little itC y in Itself": Middle-Class Aspirations in Bangor, Maine, 1880-1920" (2001). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 197. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/197 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. "THE LITTLE CITY IN ITSELF": MIDDLE-CLASS ASPIRATIONS IN BANGOR, MAINE, 1880-1920 By Sara K. Martin Thesis Advisor: Dr. Martha McNamara An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in History) December, 2001 This thesis examines the inception and growth of "the Little City in Itself," a residential neighborhood in Bangor, Maine, as a case study of middle-class suburbanization and domestic life in small cities around the turn of the twentieth century. The development of Little City is the story of builders' and residents' efforts to shape a middle-class neighborhood in a small American city, a place distinct from the crowded downtown neighborhoods of immigrants and the elegant mansions of the wealthy. The purpose of this study is to explore builders' response to the aspirations of the neighborhood's residents for home and neighborhood from 1880 to 1920, and thus to provide insight into urban growth and ideals of family life in small American cities. -

Dear Sharon Gin, Refer to File 12-0303, We Are Pleased to Present

Dear Sharon Gin, Refer to File 12-0303, We are pleased to present you with this petition affirming one simple statement: "Stop the Hollywood Community Plan in its current form. Help us maintain our community, and improve infrastructure and services rather than increasing density, traffic, noise and congestion." Attached is a list of individuals who have added their names to this petition, as well as additional comments written by the petition signers themselves. Sincerely, Schelley Kiah 1 Saving historic structures in Hollywood only makes sense. Tourists come from all over the world to see the original Hollywood. Peggy Webber Mc Clory Hollywood, CA Apr 17, 2012 lindarochelle LA, CA Apr 17, 2012 Martha Widmann Three Rivers, CA Apr 17, 2012 Here's signature 763. Why won't those bastards at city hall allow us just SOME quality of life? I'm almost 70 and beginning to use the word "HATE" with respect to just about every politician in or out of office, especially the Left. Royan Herman LA, CA Apr 17, 2012 Nancy Girten Los Angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 rebecca simmons los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 albert simmons los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Infrastructure must be repaired and updated BEFORE any further density is allowed. Dana K. Los Angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 nathalie sejean los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Veronica Wallace sunland, CA Apr 17, 2012 2 Frank Freiling los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Hollywood has its own charm. Trying to Manhattanize it would wreck the neighbourhood! Bruce Toronto, Canada Apr 17, 2012 Joanne los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Lisa Meadows los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Ron Meadows los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Arsen laramians Tujunga, CA Apr 17, 2012 Scott Milan los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Scott Milan los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Janey chadwick los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Madonna stillman los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Jim smith los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 Kipling Lee Obenauf los angeles, CA 3 Apr 17, 2012 Kipling Lee Obenauf los angeles, CA Apr 17, 2012 i agree, the Hollywood Community Plan in its present form should be stopped. -

STAFF REPORT for CALENDAR ITEM NO.: 9 for the MEETING OF: September 14, 2017

STAFF REPORT FOR CALENDAR ITEM NO.: 9 FOR THE MEETING OF: September 14, 2017 TRANSBAY JOINT POWERS AUTHORITY BRIEF DESCRIPTION: Adopt rules and regulations for the TJPA’s park on the roof of the transit center, and authorize staff to proceed with requesting proposed amendments to the San Francisco Municipal Code to make TJPA’s park a “park” subject to certain rules and regulations under the Municipal Code. EXPLANATION: The 5.4-acre park and botanical garden on the roof of the Salesforce Transit Center (named “Salesforce Park” and referred to herein as “TJPA’s park”) will be a unique open space and amenity in an area of the City with few parks. TJPA’s park is expected to be a destination for visitors that will include area residents, workers, transit riders and tourists, with programs and events (activation) designed to ensure that the open space is populated throughout the daytime and evening hours of operation. The TJPA is developing a park security program that will support the following goals: • Create an exceptional visitor experience • Preserve the park’s unique ecosystem • Enable full activation of the park • Provide a safe and secure park for all users Most San Francisco parks are owned by the City and County of San Francisco; are under the control, management, and direction of the San Francisco Recreation and Park Commission and the Recreation and Parks Department staff; and are subject to the rules and regulations in the San Francisco Park Code and other provisions of the Municipal Code. The TJPA’s park, like all other San Francisco parks, requires rules and regulations to ensure the enjoyment and safety of all visitors and preservation of the public resource. -

744 Montgomery Street SAN FRANCISCO | CALIFORNIA

FOR LEASE | OFFICE SPACE 744 Montgomery Street SAN FRANCISCO | CALIFORNIA 3,500 SF MARKET READY FULL FLOOR IN JACKSON SQUARE 499 Jackson - 744 Montgomery is a building with boutique full floor opportunities, and an exclusive roof deck in a prime Jackson Square location. Rebuilt in 1965, and recently renovated, the buiding has a mix of modern infractructure and historic charm. With abundant dining and entertainment nearby and close proximity to the Financial District’s transportation options, 744 Montgomery is a unique office opportunity for discerning companies. FOR LEASE | OFFICE SPACE 744 Montgomery PRIME JACKSON SQUARE OPPORTUNITY 1ST FLOOR | SUITE 120 > 1,457 RSF > Private Entrance from Lobby > Engineered Wood Flooring Throughout > 3 Offices > 1 Conference Room > Open Space for 6-10 Workstations > Available January 1, 2017 JACKSON STREET JACKSON STREET VESTIBULE 1 ELEV DN DN LOBBY DISPLAY UP AREA EET R ST Y R E M Office GO T N OPEN TO 120 O BELOW M Office MONTGOMERY STREET MONTGOMERY P U U U P P Office VESTIBULE 3 Contact Us JIM SOBEL BRENDON KANE 415 288 7804 415 288 7868 COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL 101 Second Street , Floor 11 LIC. 00965752 LIC. 01884552 San Francisco, CA 94105 [email protected] [email protected] www.colliers.com FOR LEASE | OFFICE SPACE 744JEFFERSON ST. Montgomery PRIMEBEACH ST. JACKSON SQUARE OPPORTUNITY NORTHPOINT ST. COLUMBUS ST. Neighborhood Restaurants BAY ST. BAY ST. VANDEWATER ST. MIDWAY ST. MIDWAY BRET HARTE WORDEN ST. FRANCISCO ST. FRANCISCO ST. THE EMBARCADERO WATER ST. HOUSTON ST. PFEIFFER ST. BELL AIR ST. BELL CHESTNUT ST. CHESTNUT ST. VENARD FIELDING ST. -

SAN FRANCISCO 2Nd Quarter 2014 Office Market Report

SAN FRANCISCO 2nd Quarter 2014 Office Market Report Historical Asking Rental Rates (Direct, FSG) SF MARKET OVERVIEW $60.00 $57.00 $55.00 $53.50 $52.50 $53.00 $52.00 $50.50 $52.00 Prepared by Kathryn Driver, Market Researcher $49.00 $49.00 $50.00 $50.00 $47.50 $48.50 $48.50 $47.00 $46.00 $44.50 $43.00 Approaching the second half of 2014, the job market in San Francisco is $40.00 continuing to grow. With over 465,000 city residents employed, the San $30.00 Francisco unemployment rate dropped to 4.4%, the lowest the county has witnessed since 2008 and the third-lowest in California. The two counties with $20.00 lower unemployment rates are neighboring San Mateo and Marin counties, $10.00 a mark of the success of the region. The technology sector has been and continues to be a large contributor to this success, accounting for 30% of job $0.00 growth since 2010 and accounting for over 1.5 million sf of leased office space Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 2012 2012 2012 2013 2013 2013 2013 2014 2014 this quarter. Class A Class B Pre-leasing large blocks of space remains a prime option for large tech Historical Vacancy Rates companies looking to grow within the city. Three of the top 5 deals involved 16.0% pre-leasing, including Salesforce who took over half of the Transbay Tower 14.0% (delivering Q1 2017) with a 713,727 sf lease. Other pre-leases included two 12.0% full buildings: LinkedIn signed a deal for all 450,000 sf at 222 2nd Street as well 10.0% as Splunk, who grabbed all 182,000 sf at 270 Brannan Street. -

Edited by Richard T. Legates and Frederic Stout

THE CITY READER Second edition edited by Richard T. LeGates and Frederic Stout London and New York CONTENTS List of plates xn Acknowledgements xiii Introduction xv PROLOGUE KINGSLEY DAVIS 1965 "The Urbanization of the Human Population" 3 Scientific American 1 THE EVOLUTION OF CITIES Introduction 17 V. GORDON CHILDE 1950 "The Urban Revolution" 22 Town Planning Review H. D. F. KITTO 1951 "The Polis" 31 from The Greeks HENRI PIRENNE 1925 "City Origins" and "Cities and European Civilization" 37 from Medieval Cities FRIEDRICH ENGELS 1845 "The Great Towns" 46 from The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 W. E. B. DU BOIS 1899 "The Negro Problems of Philadelphia," "The Question of Earning a Living" and "Color Prejudice" 56 from The Philadelphia Negro HERBERT J. GANS 1967 "Levittown and America" 63 from The Levittowners SAM BASS WARNER, JR. 1972 "The Megalopolis: 1920-" 69 from The Urban Wilderness: A History of the American City ROBERT FISHMAN 1987 "Beyond Suburbia: The Rise of the Technoburb" 77 from Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia PLATE SECTION: THE EVOLUTION OF CITIES VIM CONTENTS URBAN CULTURE AND SOCIETY Introduction 89 LEWIS MUMFORD 1937 "What Is a City" 92 Architectural Record LOUIS WIRTH 1938 "Urbanism as a Way of Life" 97 American Journal of Sociology JANE JACOBS 1961 "The Uses of Sidewalks: Safety" 106 from The Death and Life of Great American Cities WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON 1996 "From Institutional to Jobless Ghettos" 112 from When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor CHARLES MURRAY 1984 "Choosing a Future" 122 from Losing Ground: American Social Policy 1950-1980 SHARON ZUKIN 1995 "Whose Culture ? Whose City ?" 131 from The Cultures of Cities FREDERIC STOUT 1999 "Visions of a New Reality: The City and the Emergence of Modern Visual Culture" 143 PLATE SECTION: VISIONS OF A NEW REALITY 3 URBAN SPACE Introduction .149 ERNEST W. -

San Francisco

SAN FRANCISCO Click below to navigate our services EXCITING ACTIVITIES UNIQUE VENUES PRIVATE D I N I N G INSPIRING DÉCOR ENTERTAINMENT LOGISTICS SAN FRANCISCO Local Highlights Food and Wine San Francisco offer endless opportunities of epicurean delights: wine tasting at urban wineries, chocolate factories, cheese and wine experiences, customized culinary and cooking classes and our famous Ferry Building Farmers Market to name a few. Culture and Art As a diverse safe-haven, San Francisco’s culture has become an influence across the globe. It’s distinctive flavors of art, music, cuisine and architecture cross all cultural boundaries creating a unique atmosphere native to San Francisco. Adventure From horseback riding to sailing on the Bay, the Bay Area has something for every adventurer. Across the Golden Gate Bridge you’ll find yourself among the rolling hills of Marin County where beaches and hikes are plentiful. An escape from the hustle and bustle of the city is just minutes away. SAN FRANCISCO Destination Map Getting Here Airport San Francisco International Airport (SFO) Oakland International Airport (OAK) Sacramento International Airport (SMF) Mineta San Jose International Airport (SJC) Monterey Peninsula Airport Napa County Airport Sonoma County Airport Climate San Francisco has a moderate climate year-round, averaging 50°F - 65°F. Our warmest months are typically September – October, known as our Indian Summer. SAN FRANCISCO Sample Program Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Airport Group Activity Optional Daytime Airport Arrivals Activities Departures CSR Program – Meet and Greet SoulCycle Charity • Sailing the Bay Manifest coordination Ride by PRA Staff Scenic VIP Transfer • Bike the Bay with Beverages Guests ride for a cause • Alcatraz Tour during a private SoulCycle Suggested Hotel class – San Francisco's • Muir Woods & Departure Times Welcome favorite fitness craze. -

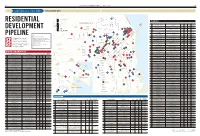

Residential Development Pipeline

36 SAN FRANCISCO BUSINESS TIMES JUNE 26, 2015 37 SAN FRANCISCO STRUCTURES SPECIAL REPORT Columbus Ave. The Embarcadero 52 SPONSORED BY Broadway Pacific Ave. Kearny St. PLANNED Stockton St. RESIDENTIAL Jackson St. Powell St. Montgomery St. SAN FRANCISCO Polk St. 80 Project name, address Developer Done Units Sale/ Market/ Sacramento St. rental affordable NP 1654 Sunnydale Ave. Mercy Housing California, Related Cos. 2018+ 1,700 both both 34 40 78 106 DEVELOPMENT 14 Pine St. 77 Potrero Terrace, 1095 Connecticut St. Bridge Housing Corp. 2018 1,400- both both California St. Bush St. 60 7 85 71 58 Sutter St. Spear St. 1,700 79 8 1 Main St. Mission Rock, Seawall Lot 227 and SWL 337 Associates LLC (S.F. Giants) 2017+ 1,500 TBD both Gough St. 112 35 80 5 Beale St. 72 Laguna St. 113 Webster St. Pier 48 38 Fremont St. Steiner St. Geary Blvd. 90 33 Pier 70 residential Forest City 2029 1,000- both both Divisadero St. 55 48 73 KEY 95 118 107 10 2,000 PIPELINE 2nd St. NP: Not placed; outside map area 96 Market St. 103 Van Ness Ave. 64 Ellis St. 62 61 74 700 Innes St. Build Inc. 2020 980 rent market Market: A majority of units are market rate, 29 94 1st St. Residential projects in 75 10 S. Van Ness Ave. Crescent Heights 2018+ 767 TBD market though almost all projects include some affordable Geary Blvd. Mission St. 97 San Francisco of 60 units units to comply with city regulations Turk St. 102 76 5M at Fifth and Mission Streets Forest City / Hearst Corp.